Among all the chronicles and annals from the Middle Ages, none is quite like the story Galbert of Bruges wrote.

The work written by this notary, the De multro, traditione, et occisione gloriosi Karolis comitis Flandriarum, tells

how Charles, count of Flanders, was murdered by his own vassals, and the ensuing warfare that raged throughout

this small territory in the years 1127 to 1128. He is not the only contemporary to write about the events that occurred,

but Galbert was an eyewitness to many of the events of this war, and he recorded just a few days after they occurred.

A reader of his work might find it very similar to a newspaper report, with daily accounts of what was happening.

The end result is one of the most fascinating stories from medieval times.

Among all the chronicles and annals from the Middle Ages, none is quite like the story Galbert of Bruges wrote.

The work written by this notary, the De multro, traditione, et occisione gloriosi Karolis comitis Flandriarum, tells

how Charles, count of Flanders, was murdered by his own vassals, and the ensuing warfare that raged throughout

this small territory in the years 1127 to 1128. He is not the only contemporary to write about the events that occurred,

but Galbert was an eyewitness to many of the events of this war, and he recorded just a few days after they occurred.

A reader of his work might find it very similar to a newspaper report, with daily accounts of what was happening.

The end result is one of the most fascinating stories from medieval times.

This article will analyze some of the statements left behind by Galbert of Bruges, to show he described war and combat, and how his writings have changed our understanding of warfare in the High Middle Ages. One can think of this as introduction or teaser for Galbert's own writings, which are far more interesting than I can make them out to be.

Synopsis

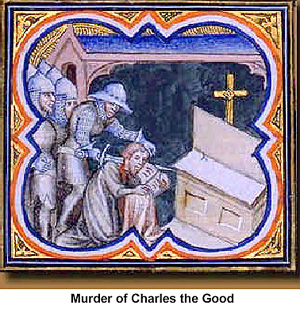

Before we get into what Galbert has to say, a very quick synopsis of what occurred is necessary: on March 2, 1127, Charles the Good, count of Flanders, was betrayed and murdered inside a church in the city of Bruges, by a group of nobles, who feared that the count was going to strip them of their power, wealth and status. Although they first thought that they would be able to get away unpunished for their crime, on March 9th the townsmen of Bruges rose up against them. The traitors and their supporters were able to barricade themselves with the castle of Bruges, were they were besieged for the next six weeks.

Those loyal to their dead count joined in on the siege, and soon after the arrival of the French king Louis the Fat; the besieged were forced to surrender. After this a short war took place to determine who became the next count of Flanders, and the spoil went to William Clito, a distant relative of Count Charles. His rule lasted little more than a year, however, as he died from wounds in a battle with Thierry of Alsace, the man who would take over the county and restore peace to Flanders.

Galbert of Bruges was uniquely situated to

record these events. He worked as a notary for

Count Charles, a position where he kept track of

records and would have needed to known how to

write. He was in Bruges when the count was

murdered, and perhaps was held prisoner by the

traitors for a few days afterwards. Once the siege

started, Galbert stood on the sidelines, observing

and taking notes on what was happening around

him. Galbert writes:

Galbert of Bruges was uniquely situated to

record these events. He worked as a notary for

Count Charles, a position where he kept track of

records and would have needed to known how to

write. He was in Bruges when the count was

murdered, and perhaps was held prisoner by the

traitors for a few days afterwards. Once the siege

started, Galbert stood on the sidelines, observing

and taking notes on what was happening around

him. Galbert writes:

- And it should be known that I, Galbert, a notary, though I had no suitable place for

writing, set down on tablets a summary of events; I did this in the midst of such a great

tumult and the burning of so many houses, set on fire by lighted arrows shot onto the roofs of the town from within

the castle (and also by brigands from the outside in the hopes of looting) and in the midst of so much danger by

night and conflict by day. I had to wait for moments of peace during the night or day to set in order the present

account of events as they happened, and in this way, though in great straits, I transcribed for the faithful what you

see and read. I have not set down individual deeds because they were so numerous and so intermingled but only

noted carefully what was decreed and done by common action throughout the siege, and the reasons for it; and

this I have forced myself, almost unwillingly, to commit to writing.

Galbert seems to have the made notes every day or so during the siege, and a few months later he used them to write his account. Much of which he wrote he observed first-hand, but at other times he relates what he had read or heard from others – this would have been true for everything that took place outside of Bruges.

What makes Galbert so interesting for medieval historians is that he is very detailed in his writing, giving us long descriptions of what he found intersting or noteworthy. Moreover, he also gives us his opinions on the events going on around him, and he was not adverse to criticize the side he supported. Galbert sometimes gets carried away with himself, adding what he thought other people were thinking as they were being led away to death.

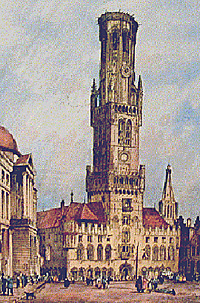

A large proportion of his work describes the siege of the

castle of Bruges, which lasted from March 9th, 1127 to April 19th.

It is hard to estimate how many people were involved in the

siege, since no numbers are provided by Galbert or any other

writer, but it seems that several hundred men were besieging a

few dozen men in the castle. Initially the traitors were besieged

by the townsmen of Bruges and a few supporters of the count,

but over the next several days nobles and townsmen from

throughout Flanders joined the besiegers.

A large proportion of his work describes the siege of the

castle of Bruges, which lasted from March 9th, 1127 to April 19th.

It is hard to estimate how many people were involved in the

siege, since no numbers are provided by Galbert or any other

writer, but it seems that several hundred men were besieging a

few dozen men in the castle. Initially the traitors were besieged

by the townsmen of Bruges and a few supporters of the count,

but over the next several days nobles and townsmen from

throughout Flanders joined the besiegers.

Many were there to avenge their fallen count, but Galbert also knew that others had less noble reasons for coming. He describes some of the men from the city of Ghent as "bold plunderers, murderers, thieves, and anyone ready to take advantage of the evils of war."

As their enemies gathered their forces in Bruges, Galbert explains that those held up in the castle were making their own preparations for the siege, "for they had blocked up the gates of the castle on the inside from bottom to top with loads of dirt and stones and dung so that they could not be reached from the outside even if by chance the gates should be destroyed."

The castle itself enclosed several buildings, including several homes and a church which had a large tower. The walls of the castle are described as "high and strong, with lookout towers and a circular walk for fighting outside."

Over the next several days, several attempts were made to storm the castle, sometimes by using ladders to scale

the walls, and other times by breaking down the gates. The besiegers efforts were thwarted, however, as those

trapped inside would throw down stones and other heavy objects at them. Galbert tells how one of the besieged, a

mercenary named Benkin, “kept going around the walls in the fighting, running here and there, and though he was

only one he seemed like more because from inside the walls he inflicted so many wounds and never stopped. And

when he was aiming at the besiegers, his drawing of the bow was identified by everyone because he would either

cause grave injury to the unarmed or put to flight those who were armed, whom his shots stupefied and stunned,

even if they did not wound.”

Over the next several days, several attempts were made to storm the castle, sometimes by using ladders to scale

the walls, and other times by breaking down the gates. The besiegers efforts were thwarted, however, as those

trapped inside would throw down stones and other heavy objects at them. Galbert tells how one of the besieged, a

mercenary named Benkin, “kept going around the walls in the fighting, running here and there, and though he was

only one he seemed like more because from inside the walls he inflicted so many wounds and never stopped. And

when he was aiming at the besiegers, his drawing of the bow was identified by everyone because he would either

cause grave injury to the unarmed or put to flight those who were armed, whom his shots stupefied and stunned,

even if they did not wound.”

Galbert seems to have spent his days watching the ongoing struggle for the castle and then writing what he saw. Here is one of his entries:

- On March 18, Friday, the ladders were brought out to the walls, and both sides attacked with

arrows and stones. Those who brought out the ladders now advanced defended by shields and

wearing coats of mail. Many followed, to see how they could set the ladders up against the walls,

because they were very burdensome owing to the fact that the wood was green and damp, and very

heavy, being about sixty feet in height; the lower ladder was twelve feet wide while the upper ladder

was much narrower but a little longer.

And while the ladders were being dragged along, the cries and shouts of the pullers aided their hands, and the noise resounded in the high heavens. The men of Ghent, in an armed band, were protecting with their shields those who were dragging the ladders, for the besieged, having heard and seen the dragging, mounted the walls and appeared on the lookout towers, hurling an infinite number of stones and a cloud of arrows against the bearers of the ladders. But notwithstanding, audacious young men, who wished to outstrip the assault of the bigger ladders, set up small ladders such as ten men are accustomed to carry, and climbed the walls one after the other. But when anyone of them reached out to grasp the summit and go over the wall, those hiding inside and lying in wait for the climbers, hurled him back with spears and pikes and javelins as he clung to the ladder so that no one, no matter how bold or swift, any longer dared to approach the besieged by the smaller ladders.

Meanwhile, others were trying to drive holes in the walls with the mallets of masons and all kinds of iron instruments, and though they tore away a great part of the wall they had to retire, frustrated. But when the crowd of pullers had come close to the walls, and the fighting grew more bitter on both sides as the overwhelming mass of stones came from inside, the dense shade of night put an end to the fighting on both sides; and the men of Ghent, suffering from many wounds, had to wait for the next day when, with the help of all the besiegers, they hoped to erect the bigger ladders by force and so gain access to the besieged.

Galbert sums up the course of the siege in the following snippet:

- In the same way, throughout the whole course of the siege, both sides stationed watches and laid

ambushes. In general, the besieged made an attack on the besiegers every night with the strongest

possible forces; and they fought more bitterly at night than by day because the besieged did not dare

to show themselves by day, in view of the shamefulness of the crime, but hoped somehow to conceal

themselves and escape, if possible, so that if by chance they did get away, no one would suspect them

of the crime of treachery.

Several of the men trapped inside the castle were able to escape as Galbert says, possibly with the assistance of some of the besiegers. Meanwhile, some of the besieged men who were not part of the original conspirarcy to murder the Count were persuaded to leave the castle voluntarily in exchange for promises that their lives would be spared. It is hard to know how many people left the castle during the siege, but it seems that no more than three dozen men were still holding out after the first week of the siege.

Few of those who fled the castle were able to hide themselves from the supporters of the Count. One of the leaders of the conspiracy, Bertulf, chancellor of Flanders, was captured near the city of Ypres. He was taken the city and hung from its gallows, where the people "set about destroying the body of the man with iron hooks, clubs, and stakes." On the same day in Ypres a knight named Guy of Steenvoorde was accused of taking part in the treason by another knight named Herman the Iron. When Guy denied the charges, Herman challenged him to single combat.

Galbert vividly records the match that followed:

- "Guy had unhorsed his adversary and kept him down with his lance just as he liked whenever

Herman tried to get up. Then his adversary, coming closer, disemboweled Guy's horse, running him

through with his sword. Guy, having slipped from his horse, rushed at his adversary with his sword

drawn. Now there was a continuous and bitter struggle, with alternating thrusts of swords, until

both, exhausted by the weight and burden of arms, threw away their shields and hastened to gain

victory in the fight by resorting to wrestling. Herman the Iron fell prostrate on the ground, and Guy

was lying on top of him smashing the knight's face and eyes with his iron gauntlets. But Herman,

prostrate, little by little regained his strength from the coolness of the earth…and cleverly lying

quiet made Guy believe he was certain of victory.

Meanwhile, gently moving his hand down to the lower edge of the cuirass where Guy was not protected, Herman seized him by the testicles, and summoning all his strength for the brief space of one moment he hurled Guy from him; by this tearing motion all the lower parts of the body were broken so that Guy, now prostrate, gave up, crying out that he was conquered and dying."

Meanwhile, after several days of frustration, the besiegers had a turn of fortune. It had become cold and rainy on the day after the failed attack by the men of Ghent, and the men guarding the walls for the besieged decided to go indoors to warm themselves.

Some of the besiegers noticed this and a few of them used small rope ladders to climb over the walls and into the castle courtyard. There they found a small side door along the wall that had not been barricaded with stones and debris. They opened the door, allowing the other besiegers to storm into the castle. A violent struggle then took place, with the besieged having to retreat into the castle's church. Meanwhile many other people swarmed into the castle to loot whatever they could, with items ranging from mattresses to manacles to foodstuffs.

Over the next few days, the besieged were forced to relinquish part of the church, where they held out hope that they would be relieved by their friends and allies. Galbert describes how they exchanged taunts and insults with their attackers and would sound off a horn in each night to remind everyone that they were still alive and determined to keep fighting.

But the hopes of the besieged were given an even greater setback when Louis the Fat, King of France arrived in Bruges in early April. He was the overlord to Count of Flanders, and had now arrived with William Clito, his handpicked choice to succeed Charles. He immediately took charge of the siege, which had been to that point run by what could best be termed a committee of nobles and important townsmen, and which sometimes proved to be disorganized.

Over the next several days, the army under Louis took control of most of the church, forcing its defenders into its highest tower. The besiegers then started using picks and other tools to start demolishing the tower from below.

On April 19th, with tower in danger of collapsing, the remaining twenty-seven besieged men surrendered to the king. With the siege finally over, and most of the conspirators and their followers captured, only one matter needed to be dealt with: the fate of these captives. The King and his new count decided that there punishment should be public and serve as a warning to anyone who would dare betray their lord. One by one these captives had there hands bound and were taken into the castle to its highest tower.

Once they reached this point, their guards threw them out of a window, and they crashed to the ground below. Galbert describes how one of the victims, upon reaching the precipice, "begged the king's knights who were standing by to grant him time for praying to God, and, taking pity on him, they allowed him to pray. When he had finished, the young man, so handsome in appearance, was hurled down, and falling to the earth, he met the peril of death and expired at once."

A few managed to initially survive the fall, but the guards made sure that they were refused treatment and soon they too succumbed. All of the twenty-seven man captured at the end of the siege were killed in this fashion, along with another conspirator that had been taken earlier in the fighting.

This article, of course, is no substitute for the writings of Galbert of Bruges. I encourage anyone who was interested in this story to try and get a copy of this text, which has been translated into English by James Bruce Ross in his work The Murder of Charles the Good. Very few medieval writers were able to come up with such a detailed account of war, and make it into a story that is both riveting and full of surprises. For the scholar interested in medieval military history, this text is extremely valuable, as it shows many aspects of warfare that have been overlooked by other historians.

For instance, the role of non-nobles in this siege is given a great deal of prominence. From the mercenary Benkin to the men from Ghent, one sees people who are trained in weaponry and in fighting, yet who are not considered as part of the warrior class of the Middle Ages.

Many chronicles and texts from the medieval period give only the tersest descriptions of battles and sieges, leaving the modern-day reader with knowing little more than which side had won. But there are other works, like the biography of William the Marshal or Nicolo Barbaro's Diary of the Siege of Constantinople in 1453, which offer immensely important descriptions of warfare. The writings of Galbert of Bruges can be considered one of the best accounts ever given of a medieval siege, and one of the most illuminating texts on practice of warfare during this period.

Further Reading:

Galbert of Bruges, The Murder of Charles the Good, trans. James Bruce Ross. Originally published in 1959, several reprints of this work has been made.

Jeff Rider, God's Scribe: The Historiographical Art of Galbert of Bruges (Washington, 2001) – an analysis of how Galbert wrote his account.

Lawrence W. Marvin, "`...Men famous in combat and battle...': Common soldiers and the siege of Bruges, 1127," Journal of Medieval History v.24 i.3 (September 1998) pp. 243-258.

John Kaminiates, The Capture of Thessaloniki, edited and translated by David Frendo and Athanasios (Australian Association for Byzantine Studies, 2000) – a long letter describing the siege and capture of this Greek city in 904.

History of William Marshal, edited and translated by A.J. Holden, S. Gregory & D. Crouch (Anglo-Norman Text Society, 2002-) – this is a biography of one England's greatest knights, written shortly after his death in the early 13th century. This edition, which is the first English translation to be made of the whole text, will be coming out in 3 volumes, the first of which is now available.

Nicolo Barbaro, Diary of the Siege of Constantinople 1453, translated by John Melville-Jones (New York, 1969) – the largest of several accounts of this important siege, and like Galbert of Bruges, is written with almost daily entries.

Alessandro Beneditti, Diari de Bello Carolino (Diary of the Caroline War), translated by Dorothy M. Schullian (New York: Renaissance Society of America, 1967) – this account of warfare in late-15th century Italy comes from a Venetian physician who accompanied his city's armies for several months.

Portions of these works, as well as Galbert's account, are available online at the website for De Re Militari: The Society for Medieval Military History (www.deremilitari.org)

Back to Cry Havoc! # 46 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc! List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com