In the early years of the 11th Century, the Byzantine Empire and the Arab Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad were the two great powers of the Western Mediterranean. However, both were in decline; the Byzantines were cursed with a succession of incompetent emperors, while the Abbasid Caliphate bled itself white in wars with the Shi’ite Fatimids in Egypt and began to disintegrate. Beginning in 1037, a force that would shake both empires to their very foundations began moving west from Central Asia. That force, the Seljuk Turks, would subjugate the Abbasids and, in the 1071 Battle of Manzikert, cripple the Byzantine Empire. The consequences of that battle would echo through the centuries; the Crusades and the Byzantines’ ultimate fall to the Ottoman Turks all resulted from what the Byzantines called “that dreadful day.”

In the early years of the 11th Century, the Byzantine Empire and the Arab Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad were the two great powers of the Western Mediterranean. However, both were in decline; the Byzantines were cursed with a succession of incompetent emperors, while the Abbasid Caliphate bled itself white in wars with the Shi’ite Fatimids in Egypt and began to disintegrate. Beginning in 1037, a force that would shake both empires to their very foundations began moving west from Central Asia. That force, the Seljuk Turks, would subjugate the Abbasids and, in the 1071 Battle of Manzikert, cripple the Byzantine Empire. The consequences of that battle would echo through the centuries; the Crusades and the Byzantines’ ultimate fall to the Ottoman Turks all resulted from what the Byzantines called “that dreadful day.”

Byzantine Military in Shambles

In 1037, the Seljuk Turks under Tugrul Beg left their Central Asian homeland and began moving into the northern reaches of Persia to take advantage of the crumbling eastern borders of the Abbasid Caliphate. They first settled in present-day Azerbaijan and used it as a springboard for further conquests. In 1040, the Seljuks defeated the Ghaznavids, another Turkic tribe, and soon spread across all of Persia, setting up their capital at Isfahan. Tugrul ultimately marched on Baghdad in 1055 and gained the titles “Ruler of the Lands of East and West” and “sultan,” meaning “holder of power,” from the Caliph, effectively adding the Abbasid Caliphate and the Arab lands it ruled to the Seljuk Empire.

During this period, the Byzantines were undergoing a period of decline. The Emperor, Constantine X Ducas, though hailing from one of the most revered families in the military aristocracy, ignored the army, persecuted the Armenians, whose views on the exact nature of Christ clashed with the Orthodox Church, and spent his time writing dissertations on the minor points of law, allowing the powerful and avaricious Byzantine bureaucracy to run the Empire. The bureaucracy hated and feared the military and their policies reflected this.

In addition to large-scale budget cuts, the generals lost power and the loyal peasants who formed the backbone of the Empire’s armies were reduced to near-serfdom by government policies favoring the great landowners (before, the government had favored the peasantry over the landed aristocracy in order to keep the aristocrats from threatening the Emperor). The Byzantine citizens were progressively replaced by (often unreliable) foreign mercenaries. The results were disastrous for the military. John Scylitzes wrote that the native Byzantine military carried “instead of swords and other weapons they held, as the Bible has it, only pikes and scythes” in wartime. They lacked horses and other equipment and were rarely paid, leaving many hungry and sick. The mercenaries, promised lands instead of money because the treasury was often bare, became a predatory landlord caste who made the peasants’ lives miserable.

The decline of the Byzantine military was a major cause of the coming disaster. In 1064, Constantine X died in 1067, but not before making his wife Eudocia promise not to marry again. His young son Michael was crowned as Michael VII, though he shared power with his two brothers and his uncle John Ducas was a major power behind the throne. Michael had the same temperament as his father and allowed the bureaucracy to continue its reign of terror; the results were obvious when the Seljuks turned their eyes westward.

The Rise of Romanus

The Seljuks and their unruly Turkmen ghazis, barely-Islamized warlords who retained the brigand ways of their ancestors and who were rarely (if ever) under the Sultan’s control, had begun making incursions into Armenia, a Byzantine client state whose militia had been disbanded by Constantine, in 1048. The conquest of Armenia was finally completed in 1064 with the sack of the capital of Ani. From there, the Seljuks under Tugrul’s successor Arp Arslan, the ‘Conquering Lion,’ raided Asia Minor, sacking Amorion, Chonae, and even Cappadocian Caesarea, near present-day Ankara, in a devastating campaign in 1067.

The Seljuks and their unruly Turkmen ghazis, barely-Islamized warlords who retained the brigand ways of their ancestors and who were rarely (if ever) under the Sultan’s control, had begun making incursions into Armenia, a Byzantine client state whose militia had been disbanded by Constantine, in 1048. The conquest of Armenia was finally completed in 1064 with the sack of the capital of Ani. From there, the Seljuks under Tugrul’s successor Arp Arslan, the ‘Conquering Lion,’ raided Asia Minor, sacking Amorion, Chonae, and even Cappadocian Caesarea, near present-day Ankara, in a devastating campaign in 1067.

This was the last straw for Eudocia. Fearing for the Empire’s fate, she decided to take matters into her own hands. Romanus Diogenes, a well-regarded member of the military aristocracy and veteran of campaigns against the fearsome Pecheneg tribe, had been accused of plotting against the weak Emperor Michael and awaited execution. Eudocia, became fascinated with him from the dungeons, first pardoing and and ultimately marriying him, violating her oath to Constantine. His coronation as Romanus IV displaced the sons of Constantine a la Hamlet and earned the new Emperor and his bride the undying enmity of the Ducas family. This powerful family included many important political and military leaders in the Empire, and their desire for vengeance would bring him grief later.

Once crowned, Romanus IV launched expeditions to the East in 1068 and 1069, which succeeded in capturing Hieropolis in present-day Syria and driving the Seljuks beyond the Euphrates river, and spent the remainder of his time repairing the damage that the bureaucracy had done to the military in preparation for his final campaign to end the threat of the Seljuks. In the second week of March, 1071, Romanus set off to the east with between 60,000 and 70,000 soldiers. About half were mercenaries, holdovers from the time when mercenaries largely replaced the native military or soldiers especially hired for the campaign, including the Norsemen of the Varangian Guard, Normans and Franks from what is now France, Slavs from the north, and even some Turks of dubious loyalties.

At Erzurum in eastern Turkey, Romanus split his army in two. The larger part, including the entire contingent of the Turkic Cumans, was put under his general Joseph Tarchaniotes and dispatched it to the town of Khelat, near the northern shore of nearby Lake Van. Romanus led the rest of the army headed off towards the town of Manzikert itself, which fell bloodlessly. No one knows what happened to Tarchaniotes’ force, which was between 30,000 and 40,000 men, larger than that of the Seljuks. Muslim sources suggest that Arslan obliterated the army in a pitched battle, while the Byzantine historian Michael Attaleiates, who was present at the battle itself, claimed that Tarchaniotes’ army took one look at the Seljuk force and ran for their lives, with the general at the front. Modern-day historian John Julius Norwich suggests that Tarchaniotes was an agent of the vengeful Ducas family. Either way, when Romanus faced the Seljuks, he had already lost half his army.

Events Set in Motion

The day after the Byzantines reclaimed Manzikert, Seljuk bowmen constantly harassed the Emperor’s forces and even wounded Romanus’s co-commander, Nichephorus Bryennius. Bacilacius, commander of the forces raised from the Theodosipolitan theme (military district) near Erzurum, pursued a group of Seljuk scouts into an ambush and his entire force was either captured or killed. During the long moonless night, the Seljuks raided the Byzantines, causing such trouble that on several occasions, it was thought that they had

overrun the camp. During that night, a group of Turkic Uz mercenaries had defected to the Seljuks. It was under these circumstances that ambassadors from Alp Arslan arrived, offering a truce.

The day after the Byzantines reclaimed Manzikert, Seljuk bowmen constantly harassed the Emperor’s forces and even wounded Romanus’s co-commander, Nichephorus Bryennius. Bacilacius, commander of the forces raised from the Theodosipolitan theme (military district) near Erzurum, pursued a group of Seljuk scouts into an ambush and his entire force was either captured or killed. During the long moonless night, the Seljuks raided the Byzantines, causing such trouble that on several occasions, it was thought that they had

overrun the camp. During that night, a group of Turkic Uz mercenaries had defected to the Seljuks. It was under these circumstances that ambassadors from Alp Arslan arrived, offering a truce.

The Sultan apparently was unsure about whether his forces were capable of defeating the Byzantines in a pitched battle, casting doubt on the theory that he had overpowered the other Byzantine host earlier. Despite the assurances of his general Afshin, who had penetrated deep into Byzantine territory during the earlier raids and informed his sovereign that the Byzantines were weak and easily destroyed, he worried that he might be defeated and made preparations for his death. Arslan made sure that the other Turkish nobles would accept his son Malik Shah as his successor, he spoke of possible “martyrdom,” and planned on wearing white to battle so that his clothing could also be his burial shroud.

The Empire also was not his highest priority; he had been besieging Fatimid-held Damascus in Syria (taking advantage of a Sunni uprising in Egypt led by a Turkic general) when word came that the Byzantine army was moving towards the Seljuk borders. The only disagreement he had with Romanus was that the Byzantines were intent on taking what the Sultan believed was more than their fair share of Armenian territory, including, the northern and western portions that Arslan believed were needed for defending the Seljuk Empire; he believed a mutually acceptable partition could be achieved and then he would set off to deal with the Egyptians, his real enemy all along. He hoped to avoid fighting altogether.

Romanus, however, had other plans. He wanted to end the menace of the Seljuk raids once and for all by wiping out the core of the Seljuk state, its army and its Sultan, and he already commanded a larger force than he would ever likely command again due to the decay of the Empire and its military. Besides, the issue had a political dimension. If he did not return to Constantinople in triumph, the Ducas family plots against him would grow and gain support and his life and throne would be in grave jeopardy. He sent the ambassadors away and prepared for battle. That battle would come on Friday, August 26th, 1071.

The Battle Begins

The battle began with the Byzantine infantry arranged in one line several ranks deep, flanked on both sides by the cavalry. Romanus commanded the center and the best Byzantine regulars, with Bryennius commanding the left, which largely consisted of Uz Turks, and a Cappadocian named Alyattes on the right, whose forces were largely Pechenegs intent on looting. The large rearguard consisted of the great landowners’ private armies and was led by Andronicus Ducas, the nephew of Constantine X and a bitter enemy of the Emperor. One wonders why he was even allowed to go on the campaign; one possibility is that if he remained behind, Romanus feared he would try to seize the throne for his family and wanted him where he could keep an eye on him. Either way, Ducas, who was described as being cunning and “marvelously trained…in stratagems,” was able to conduct one of the most devastating

betrayals of Byzantine history.

The battle began with the Byzantine infantry arranged in one line several ranks deep, flanked on both sides by the cavalry. Romanus commanded the center and the best Byzantine regulars, with Bryennius commanding the left, which largely consisted of Uz Turks, and a Cappadocian named Alyattes on the right, whose forces were largely Pechenegs intent on looting. The large rearguard consisted of the great landowners’ private armies and was led by Andronicus Ducas, the nephew of Constantine X and a bitter enemy of the Emperor. One wonders why he was even allowed to go on the campaign; one possibility is that if he remained behind, Romanus feared he would try to seize the throne for his family and wanted him where he could keep an eye on him. Either way, Ducas, who was described as being cunning and “marvelously trained…in stratagems,” was able to conduct one of the most devastating

betrayals of Byzantine history.

The Seljuks retreated in a broad crescent, leaving their mounted archers to badger the Byzantines’ flanks and draw the Byzantine cavalry into well-planned ambushes. The Byzantines had gone into battle with the goal of closing with the enemy, where they could take advantage of their greater skill in hand-to-hand combat and avoid being devastated from a distance by Seljuk arrows. However, except for harassing the flanks, the Turks refused to close with the Byzantine center, frustrating Romanus. The Byzantines continued moving forward through the entire day until night began to fall, when Romanus realized their camp with all its supplies had been left with almost no defense. He ordered his standard bearer to reverse the Imperial standard and wheeled his horse.

The Sultan had been watching Romanus from the hills above and this was the moment he had waited for. He ordered the attack. From the hills, the Turks swept down on top of the center of the Byzantine lines, separating the main body of the troops from the rearguard. Many of the mercenaries, not knowing what the reversal of the standard meant, assumed the Emperor had been killed and retreated. However, all was not lost. Had Andronicus Ducas and the rearguard acted promptly, they could have pinned the Turks against the forward units and trapped them. However, his family’s grudge against the Emperor bore bitter fruit…

Treachery and Defeat

Rather than leading the rearguard against the Turks, Ducas proclaimed that the Emperor had fallen, the battle was lost, and the rearguard needed to save itself. The rearguard retreated and the panic spread among other units. As the army began to disintegrate, the Byzantine left wing saw the Emperor and his forces surrounded by Turks and moved to help them. However, the Seljuk forces hit them from behind and they were also forced to retreat, leaving the center alone to face the Turkish storm.

Rather than leading the rearguard against the Turks, Ducas proclaimed that the Emperor had fallen, the battle was lost, and the rearguard needed to save itself. The rearguard retreated and the panic spread among other units. As the army began to disintegrate, the Byzantine left wing saw the Emperor and his forces surrounded by Turks and moved to help them. However, the Seljuk forces hit them from behind and they were also forced to retreat, leaving the center alone to face the Turkish storm.

Romanus tried to rally the troops from his position in the center, but the situation was turning into a rout. He was left alone in the midst of the battle and refused to flee, killing several Turkish soldiers and fighting until, swamped by enemies and with his horse killed under him, his sword hand was wounded. He was left on the battlefield with the dead and wounded during the night and the next day he was brought before the Sultan in chains.

The Sultan did not believe that the captive was actually the Emperor until Bacilacius, the theme commander captured at the beginning of the battle, identified him. Once he knew his captive’s identity, Arslan was extremely courteous. After placing his foot on Romanus’s neck and making him kiss the ground at his feet in a symbolic gesture of defeat, he treated Romanus kindly and allowed him to remain his guest and eat at his table. In addition to simple politeness, Arslan had a goal in mind. The return of a friendly (or at least sufficiently cowed) Romanus to Constantinople would make sure that the peace treaty would be honored and prevent an aggressive and vengeful Byzantine leader from assuming the throne and launching a new war.

In exchange for peace, he asked for possession of Manzikert, Antioch, Edessa, and Hieropolis, plus one of Romanus’s daughters as a bride for his own son. In addition, there was ransom for the Emperor himself of one and a half million gold pieces and a further three hundred and sixty thousand as annual tribute, down from the ten million gold pieces Arslan had demanded earlier before Romanus explained that the Byzantine Empire simply did not possess that much money after his military reforms and the launch of the great campaign to the east.

The peace was negotiated quickly and, a week after the battle ended, Romanus left Arslan’s camp with many gifts and an honor guard of two Seljuk Emirs and one hundred Mameluke warriors. He headed back to Constantinople and, hopefully, to his throne.

More Treachery

Unfortunately for Romanus, that was not to be. The previous April, a mere month after he had left for the East, the Norman leader Robert Guiscard had seized the city of Bari after a strenuous siege and ended five centuries of Byzantine rule in Italy. Manzikert, the second disaster in an already-terrible year, spelled the end of Romanus. John Ducas, who had the backing of the Varangian Guard, had Michael re-crowned Emperor, and exiled Eudocia to a convent. Michael was a figurehead; as before, John ruled all from behind the scenes.

Romanus’s marched on Constantinople with his Seljuk escort and the remnants of his great army that he had managed to gather to him and was defeated in two battles; in the latter, near Adana in Cicilia, his enemies were led by the traitor Andronicus Ducas. Romanus made an agreement with the Emperor Michael; he would renounce all claims to the Byzantine throne and retire to a monastery in exchange for his personal safety. Andronicus spitefully insisted on mounting him on a donkey for the trip and onlookers, possibly on the orders of vengeful Emperor Michael, attacked him and gouged out his eyes. His wounds infected and “his face and head alive with worms” he died in the summer of 1072 a few days after receiving a mocking letter from an ally of the Ducas family congratulating him on losing his eyes, supposedly a clear signal from God that he was worthy of a higher light.

Undoing The Empire

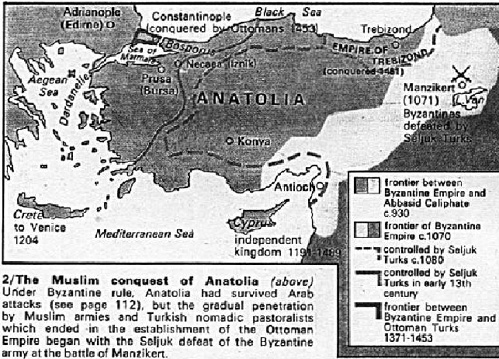

Arp Arslan had no intentions of conquering Asia Minor; as before, his highest priority was war with the Fatimids in Egypt. However, the collapse of Byzantine authority in the aftermath of Romanus’s overthrow enabled the ghazis and other Turkish warlords to lead incursions into Byzantine territory independent of the sultan’s control. The Sultan himself was not particularly inclined to stop his subordinates from raiding Anatolia; according to Matthew of Edessa, he flew into a rage upon discovering what happened to Romanus, denounced the Byzantines as “all atheists,” and did nothing to stop the activity of the ghazis.

Fernand Braudel in the second volume of The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Phillip II, states the “troubled frontiers of Asia Minor [were] a rendezvous for adventurers and fanatics.” Beginning in 1073, Turkish tribesmen moved into central Asia Minor, the source of much of the Empire’s grain, a major part of the tax base, and the primary recruiting ground for its native military, in search of lands to rule and infidels to fight.

There was little organized Byzantine resistance to this invasion until much later due to revolts breaking out in multiple parts of the Empire against the Ducas family’s misrule, which caused inflation so severe that the Byzantine currency lost a quarter of its value, and seeming inability to defend the Byzantine state against the Turkic raiders. In fact, rival Byzantine factions bid against each other for Turkish aid and some even allowed the tribesmen to occupy urban centers in Asia Minor, including some valuable port cities in the west, which the ghazis were unable to take for themselves for lack of siege equipment. Turkish warlords raided as far as Trebizond in the northeast, the Aegean coastline in the west, and Antioch further south. Most Byzantine urban centers managed to hold out due to the raiders’ lack of siege equipment, but the Turks ruled and ravaged the countryside. In addition to raiding, numerous small Turkic principalities were set up on Byzantine territory. The situation ultimately became so bad that in 1090-1, Tzachus, Emir of Smyrna on the Aegean coast, besieged Constantinople itself.

Anatolia: Crucible of Conflict

During this period, opposition to the Turkish conquest and settlement was mostly left to the Christian akritai, superstitious irregulars with more similarities to the ghazis than their co-religionists in Constantinople. In the violent frontier culture that existed in Anatolia between the beginnings of Turkish settlement and the 1176 Byzantine defeat at Myriocephalum that ended Byzantine efforts to reclaim the region, the Islamic elements ultimately became the dominant cultural force. The akritai, abandoned by their Byzantine patrons after 1176, either became assimilated into the Turkic culture or fled into the Byzantine Empire’s remaining European possessions, ending armed resistance to Turkish rule.

During this period, opposition to the Turkish conquest and settlement was mostly left to the Christian akritai, superstitious irregulars with more similarities to the ghazis than their co-religionists in Constantinople. In the violent frontier culture that existed in Anatolia between the beginnings of Turkish settlement and the 1176 Byzantine defeat at Myriocephalum that ended Byzantine efforts to reclaim the region, the Islamic elements ultimately became the dominant cultural force. The akritai, abandoned by their Byzantine patrons after 1176, either became assimilated into the Turkic culture or fled into the Byzantine Empire’s remaining European possessions, ending armed resistance to Turkish rule.

That resistance was hardly uniform. Due to the abuses suffered by the peasants of Asia Minor at the hands of the Byzantine nobility and foreign mercenary landlords, many Byzantine subjects greeted the Turks as liberators. The Turkish warriors established themselves as the newer and generally more easygoing landlords, married local women, and fathered children who were brought up as Muslims and Turkic-speakers. In addition, the Mevlevi (“Whirling”) order of dervishes, based in Seljuk Konya (formerly Iconium), served as very effective missionaries.

Increasing numbers of the local people began to convert to Islam, solidifying the Turkish hold. Other ghazis used violent means to accomplish the Islamification of Asia Minor; the Byzantine princess Anna Comnena wrote about the destruction of cities and massacres of civilians as a result of the Seljuk arrival in Anatolia and Matthew of Edessa describes how the massacre of the rural populace led to the collapse of agriculture and famine. These violent events led to the flight of thousands of Greek-speakers from the interior to the coastal territories still under Byzantine control or to the Empire’s European lands.

As a result of the violence of some ghazis and the tolerance of others, Turkic-speaking Muslims became the predominant demographic group in the Anatolian interior by the 13th Century. A new Seljuk state, the Sultanate of Rum (Rome) was founded at Nicaea (present-day Iznik) in 1078 when Alp Arslan, seeking to restore order and keep control of the ghazis, dispatched his cousin Suleiman Qatalmesh to Asia Minor. Despite the cruelty displayed by some of the Turkmen warlords during the initial conquest, the Sultanate of Rum evolved into a generally tolerant environment where Christians, Jews, and Muslims coexisted peacefully and even served together in a common army. Eventually, Asia Minor was, as Jasper Streater put in a 1967 article on Manzikert, “lost forever to Christendom.”

The largest consequence of the defeat of the Byzantines at Manzikert was the call for the Crusades. In late 1094, Emperor Alexius Comnenus met with Pope Urban II and arranged for a meeting of Catholic and Orthodox churchmen in Piacenza, Italy. At this meeting in March 1095, the Byzantine delegates spoke passionately about the sufferings of the Christians in Asia Minor, the menace of the Turks, and the material benefits of a war of conquest in the East. The Emperor was hoping for limited military aid for a quick war of conquest against the Seljuks, whose realm had become divided after the death of Malik Shah; he got something else instead.

The largest consequence of the defeat of the Byzantines at Manzikert was the call for the Crusades. In late 1094, Emperor Alexius Comnenus met with Pope Urban II and arranged for a meeting of Catholic and Orthodox churchmen in Piacenza, Italy. At this meeting in March 1095, the Byzantine delegates spoke passionately about the sufferings of the Christians in Asia Minor, the menace of the Turks, and the material benefits of a war of conquest in the East. The Emperor was hoping for limited military aid for a quick war of conquest against the Seljuks, whose realm had become divided after the death of Malik Shah; he got something else instead.

The Pope took the Byzantines’ appeal for military assistance for a war of re-conquest in Asia Minor and in a speech on November 25th, 1095, transformed it into a full-blown Holy War not only to assist the Byzantines, but also to seize Jerusalem and the Holy Land from the Seljuks. The Seljuks had driven the Fatimids out of the Levant and their ghazis plundered caravans of Christian pilgrims, virtually cutting off access to the Holy Land by 1090 and providing the Latin Christians with a casus belli.

The First Crusade began in 1096.

The invasion of Anatolia and the Holy Land by the Latin Christians weakened the Sultanate of Rum and led to Byzantine territorial gains throughout western Asia Minor, including the retrieval of the city of Nicaea in 1097, but the later Fourth Crusade proved as devastating to the Byzantine Empire as the First Crusade was to the Seljuk government of the Levant. During that crusade, the wily Doge of Venice, who viewed Byzantium as a trading rival, diverted the Crusading army from Egypt and seized Constantinople, leaving Byzantium a shattered wreck of competing states ruled by Latin nobles and different Byzantine families for decades.

When the Palaiologos dynasty, rulers of Nicaea in aftermath of the 4th Crusade, managed to drive the Latin Crusaders from the city and reestablish the Empire, the damage had been done. Bereft of most of its wealth and resources, Byzantium lingered until 1453 when the Ottoman Turks, successors to the Seljuks as the rulers of Asia Minor, finally seized Constantinople and, in the minds of some historians, began the modern era.

When the Palaiologos dynasty, rulers of Nicaea in aftermath of the 4th Crusade, managed to drive the Latin Crusaders from the city and reestablish the Empire, the damage had been done. Bereft of most of its wealth and resources, Byzantium lingered until 1453 when the Ottoman Turks, successors to the Seljuks as the rulers of Asia Minor, finally seized Constantinople and, in the minds of some historians, began the modern era.

Works Cited

Armstrong, Karen. Holy War: The Crusades and Their Impact on the Modern World. New York: Doubleday, 1991.

Duggan, T.M.P. “Friday, August 26th, 1071.” Turkish Daily News. Online.

http://www.turkishdailynews.com/old_editions/08_28_99/feature.htm

“Encyclopedia: Romanus IV.” Online. NationMaster.

http://www.nationmaster.com/encyclopedia/Romanus-IV

Friendly, Alfred. The Dreadful Day: The Battle of Manzikert, 1071. London:Hutchinson, 1981.

Gerolymatos, Andre. The Balkan Wars. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Golden, Peter B. Nomads and Sedentary Societies in Medieval Eurasia. Washington DC:American Historical Association, 1998.

Gyriacou, Charlie. “A Detailed Chronology of Greek History.” Greek Folk Dance Research Manual. Online.

http://www.filetron.com/grkmanual/detailgreekchrono.html. Accessed 8 June 2003.

Hildinger, Erik. Warriors of the Steppe: A Military History of Central Asia, 500 BC-1700 AD. New York: Sarpedon, 1997.

Humble, Richard. Warfare in the Middle Ages. Spain: Mallard Press, 1989.

“Islam in Asia: The Seljuk Turks.” Online. Islamset: Science, Environment, and Technology. http://www.islamset.com/islam/civil/seljuk.html . Accessed 14 Sept. 2003.

Jenkins, Romilly. Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries. New York: Random House, 1966.

Jones, Terry and Alan Ereira. Crusades. Great Britain: Butler and Tanner Ltd., 1995.

Norwich, John Julius. A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Norwich, John Julius. Byzantium: The Apogee. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Stewart, Desmond, and the Editors of Life. Turkey. New York: Time Incorporated, 1965.

Stoneman, Richard. A Traveler’s History of Turkey. 2nd ed. New York: Interlink Books, 1996.

“The Turks in History.” Online. Killeen Independent School District. http://killeenroos.com/4/Turkeyre.htm .

Back to Cry Havoc! #45 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc! List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com