When I came to a section concerning battles between the Roman Legions and the “Joppa Pirates” in my recently published book on the Roman-Jewish War, [ The Roman-Judaeo War, 66-74 AD: A Military Analysis] I touched briefly on the strategic significance and potential of Judaean seapower in the conflict. In researching the particulars of how the sea robbers interrupted the Roman grain supply from Alexandria, I was surprised at the sparseness of literature on the strategic situation of maritime antiquity. Certainly there are many studies of miscellaneous aspects of ancient seafaring.

When I came to a section concerning battles between the Roman Legions and the “Joppa Pirates” in my recently published book on the Roman-Jewish War, [ The Roman-Judaeo War, 66-74 AD: A Military Analysis] I touched briefly on the strategic significance and potential of Judaean seapower in the conflict. In researching the particulars of how the sea robbers interrupted the Roman grain supply from Alexandria, I was surprised at the sparseness of literature on the strategic situation of maritime antiquity. Certainly there are many studies of miscellaneous aspects of ancient seafaring.

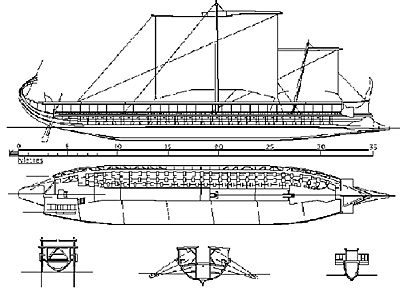

But all too few concern the general outlook (use of naval power to advance or protect “national interests”). Most of them narrowly analyze diverse technicalities that comprise the nooks and crannies of maritime archaeology. It’s not my intention to disparage the intrepid divers and researchers who have unveiled ancient shipwrecks and their cargoes, and explored the minutiae of shipbuilding, anchor-handling, rigging, the relative positions of the oar banks on a trireme, navigation tools & techniques, and shoreside logistics in antiquity. These specialist studies are the bricks and mortar of modern interpretations of ancient seapower. But for the researcher who wants a “big picture” look at the doings of ancient navies, there are remarkably few historians who have taken a Mahanian perspective on the operations of naval forces prior to the 16th century AD.

There are some older books worth a look, such as Arthur McCartney Shepard’s Sea Power in Ancient History from 1924, and Admiral Reginald Custance’s 1918 overview of the Pelopennesian struggle War at Sea: Modern Theory Ancient Practice. These books are rather outmoded, however, in that they employ a rather contemporary nationalistic, and accordingly anachronistic, viewpoint. While focusing on the tactics of the naval engagements, William L. Rodgers’ Greek and Roman Naval Warfare: A Study of Strategy, Tactics, and Ship Design from Salamis (480 B.C.) to Actium (31 B.C.) provides a solid background of the naval systems and their command in the larger scheme of things. However, Adm. Rogers tended to avoid current (late 1930s) scholarship and preferred to get on with his story. Lionel Casson has done a lively, albeit “popular” survey of matters maritime up to circa 500 AD, but his glimpses of what seapower meant in the ancient world is scattered throughout the book. His Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World is more scholarly but is more concerned with maritime technology than strategy.

Chester Starr, a well respected author on the rise and fall of ancient civilizations wrote The Influence of Sea Power on Ancient History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989; reprinted Barnes & Noble, 1998). According to Oxford’s ad men, “Starr demonstrates that control of the seas was not always a strategic necessity in the ancient world. His theory is an important corrective to the influential teachings of the strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan.” After thoroughly examining and annotating this slim pamphlet, I can only wonder why Starr acceded to Oxford’s marketing hook. This is not to say that the book is valueless. It’s a serviceable concise review of the naval factor in ancient history. The problem is that the book never comes to grips with its purported theme – the supposed insignificance of navies and merchant fleets in the affairs of ancient empires. In fact, apart from a few incoherent throwaway lines, the preponderance of the book’s exposition demonstrates pretty much the opposite of its declared intent.

Chester Starr, a well respected author on the rise and fall of ancient civilizations wrote The Influence of Sea Power on Ancient History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989; reprinted Barnes & Noble, 1998). According to Oxford’s ad men, “Starr demonstrates that control of the seas was not always a strategic necessity in the ancient world. His theory is an important corrective to the influential teachings of the strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan.” After thoroughly examining and annotating this slim pamphlet, I can only wonder why Starr acceded to Oxford’s marketing hook. This is not to say that the book is valueless. It’s a serviceable concise review of the naval factor in ancient history. The problem is that the book never comes to grips with its purported theme – the supposed insignificance of navies and merchant fleets in the affairs of ancient empires. In fact, apart from a few incoherent throwaway lines, the preponderance of the book’s exposition demonstrates pretty much the opposite of its declared intent.

In e-correspondence with some naval historians who have written on antiquity, I have had my impression confirmed. Indeed, Phillip de Souza, one of the most important authors on ancient fleets, wrote a scathing review of Starr’s alleged contra-Mahanian affidavit. De Souza’s own forthcoming Ancient Naval Warfare should go far to remedying this deficiency.

If Starr’s book is so cantankerous and bizarre, then why waste time discussing it? Well, to begin with, its inconsistency motivated me to expand on its theme in a more sober way. I am about halfway through with my study of ancient naval power projection – a slim pamphlet For another matter, the book continues to be cited in general seapower histories without challenge.

Chapter I – Ships and Seas neatly covers the origin of true seafaring , as opposed to riverine, lake, estuarial or near-coastal forays. An early example of Starr’s perverse reasoning comes in his discussion of Thutmose III. According to Starr, Thutmose, in his campaigns to Palestine avoided marching across Sinai Desert by ferrying his army by sea in vessels built in royal dockyards at Memphis. So far so good. Then Starr brings in a non-sequitur, typical of his method: “ Ships were ‘naval’ only in the sense that they assisted in a military campaign because Egypt faced no real opposition on water. The Egyptians had complete control of eastern Med. Seaboard.” To all intents and purposes, this fact demonstrates the “influence of seapower”, contrary to Starr’s thesis. How could the absence of any naval opposition prove the irrelevance of seapower?

As will be seen, Starr returns to this stubborn “logic” when discussing the so-called “Minoan Thalassocracy.” The term denotes a state or empire founded on the “rule (command) of the sea”. Starr asserts that modern historians, influenced consciously or unconsciously by Mahan and British Naval power, are too credulous about this imputed omnipotence of the Minoan war fleet. He cites Lionel Casson (“a reasonably careful scholar”) in The Ancient Mariners (1959 ed.) p. 29 where the latter says that the Minoan fleet “was a navy that successfully policed the Mediterranean for centuries.” Here Starr is careless or willfully obtuse. Note that already in 1975, the careful French maritime historian Jean Rougé had refuted Starr’s 1954 article in the journal Historia doubting the existence of a Minoan thalassocracy, making use of a more limited definition of the term in keeping with the relatively pregnable aptitude of fighting ships of the era.

Starr disputes the argument favoring the existence of Minoan seagoing “wooden walls” based on the absence of fortified palaces by noting that the sea itself was the barrier protecting the palaces rather than a fleet. Witness, (Starr goes on to say) the way that Britain was shielded from invasion by her watery moat until the Spanish Armada, when for the first time it realized the necessity of meeting the enemy at sea.

Starr disputes the argument favoring the existence of Minoan seagoing “wooden walls” based on the absence of fortified palaces by noting that the sea itself was the barrier protecting the palaces rather than a fleet. Witness, (Starr goes on to say) the way that Britain was shielded from invasion by her watery moat until the Spanish Armada, when for the first time it realized the necessity of meeting the enemy at sea.

This is absurd. It’s saying that “seapower” was irrelevant to England until the first enemy appeared that was capable of a maritime invasion --- Spain of Phillip II. The surrounding waters rather than its ships protected it up to that point in time. Then what of the Norman invasion of 1066? Did this not demonstrate superior seapower of the invader? Similarly the Viking raids of the ninth and tenth centuries --- admittedly of a transitory nature, nonetheless showed that the Northmen were preeminent upon the northwest European waters in their time.

Then Starr perseveres in his depreciation of the Minoan fleet by mentioning that if they did have such naval power, then how do we explain how the Cretans failed to thwart the 15th century BC successful invasion by the Myceneans. Starr embellishes this artifice by noting that the galleys of the second millennium did not yet have rams with which to engage an enemy by battle at sea, and thus could only have been used (citing evidence of the Thera frescoes) for coastal raids. This whole argument seems quite forced. Rougé notes that the archaeological and epigraphical evidence points to the fact that Minoans probably did not utilize specialized fighting ships but rather adapted their round, full-bellied merchantmen for the purpose. These ships were fully capable of striking out directly across open water between Crete and Egypt, contrary to Starr’s 1954 position that they would have had to make a short hop to Rhodes then hug the coast down to Egypt. It is likely that the Myceneans had developed “long ships” – rowed galleys – that could interdict and sink the clumsier Minoan vessels, thereby decimating their naval power. The presence or absence of rams is a non sequitur. What difference whether they rammed the enemy ships or simply overcame them by skilful maneuver combined with shipborne firepower – javelins, arrows, etc. Oddly, Starr cites Casson’s “Ships and Seamanship” to support him here; recall that he had earlier found Casson (in his Ancient Mariners) too credulous of the vaunted Minoan navy.

In any event, Mahan never addressed the existence of naval mastery prior to the Athenian and Roman epochs, so this “counter-Mahanian” sparring seems superfluous.

I concentrate on this opening chapter, because it is the most egregious example of setting up a straw man in the book. The balance of the chapters don’t sustain the premise of the publisher’s hyperbole. In chapter 2, “Prelude to Thalassocracy”, Starr interpolates more jarring “observations” in the midst of his rather informative exposition of the evolution of naval power. Starr cites Thucydides: “There was no warfare on land that resulted in the acquisition of an empire. What wars there were were simply frontier skirmishes” [alluding to the fact that navies were the supreme arbiters of power up to the outbreak of the Persian wars]. Starr cites this as a fascinating example, the first in Western literature, of the distorted role assigned to sea power, for the political and military conflicts of the Greek states by land actually had a very important result, the mastery by Sparta of all the Peloponnesus save for Argos. Sparta had no desire to extend its power farther, partly because it always needed to keep an eye on its helots, who revolted more than once, and by the end of the sixth century had formed a league of its dependent allies, etc.

Please note that here Thucydides was trying to make the point that in the Pelopennesian War, Athens should therefore have been the dominant power, or should have fully realized the necessity of ruling the waves. That it did not simply shows Athens’ failure to realize the potential of its naval expertise. Again, Starr’s not only is Starr’s validity defeated, but his argument is incomprehensible. Again, Starr seems to be setting up a straw man. Did Mahan claim that Athens had been a dominant naval power in the Med before 500 BC? The only place where Mahan addresses this epoch is in the brief mention in his Naval Strategy, where he is careful to spell out the relative limitations of naval “command” in contrast to that exercised by the British in the 18th and 19th centuries. In fact Starr seems to be taking Thucydides to task for percieved Mahanian excesses, a case of projecting the main battle fleet primacy claim backwards to a time when such a thing was unimaginable. While Thucydides was doubtless an admirer of Themistocles “naval preparedness”, how does this mitigate the significance of seapower already expressed in Starr’s narrative?

Just one more typical illustration will suffice:Hannibal’s “naval dilemma” in the Second Punic War. Starr contends that “contrary to the views of Mommsen and Mahan noted in the Introduction, he (Hannibal) had to march by land not simply because the Romans controlled the sea, but by reason of his large force of cavalry and elephants that could not easily have been transported by sea”. This seems like questionable logic. “Not simply [emphasis supplied] because the Romans controlled the sea”. Whether or not one can credit Hannibal’s decision to use the longer and more laborious land route to the unsuitability of ships to transport his elephants and large contingents of horses seems to beg the question. Even Starr acknowledges that it was a subsidiary reason, since Roman seapower did in fact control the narrow straits over which any seaborne attack would have to travel. In the very next paragraph, Starr remarkes that “ From time to time Carthage could muster fleets but not large enough to meet Roman naval power or to reinforce Hannibal, who finally in a truce evacuated Italy.”

It would be redundant to continue this rebuttal to Professor Starr’s oddly muddled “argument”, particularly since it fizzles out entirely by the time he reaches the time of Augustus. What, then, is Starr’s motivation for this silly polemic”

Starr informs his readers at the very beginning of the book “Mahan’s emphasis on the importance of naval superiority fitted magnificently into the bellicose, imperialistic outburst of the late nineteenth century in the United States, Great Britain and Germany”. Thus readers are warned that Mahan is to be distrusted in his deployment of historical truths. This cliché hardly merits repetition. It’s a truism that Mahan’s treatise fails to rise above the nationalistic braggadocio of his epoch. It should come as no great shock to even the modestly educated reader that political theorists do not necessarily make good historians. Potted history is also a hallmark of the works of the esteemed landpower thinkers Basil Liddell-Hart and J.F.C. Fuller among others Further, historically derived doctrines usually have a short shelf life. After a thorough search of this little tome, I found that the purported argument with Mahan occupies but a few scant sentences; its applicability to the text is imperceptible.

Why then the inflated claim to correct Mahan? My impression is that this title, ostensibly debunking Mahan, was opportune, coinciding as it did with the centennial of the latter’s seminal work on seapower. The lip service about Mahan’s errors was simply a marketing hook, packaging old wine in a new bottle. Starr, like other scholars who had made a name for themselves in a specialty, had made many books from one; he had repackaged and digested his earlier opus magnae on ancient history into mass market potboilers. The Mahan book was simply another keystroke in this outpouring.

As elucidated in Starr’s Introduction, Mahan’s memoirs trace his intuition about maritime antiquity to a brief period of leave in 1883, when he was doing some research in the English Library in Lima, Peru preparatory to a professorial posting. Captain Stephen B. Luce, founder of the Naval War College, had recently invited Mahan to become a lecturer at the new institution based on the latter’s understanding of naval affairs as demonstrated in his book about the Civil War struggle on The Gulf and Inland Waters (1883). It was during this respite from naval command that Mahan asserts he was first struck by the insight which would later make him world famous. Reading the celebrated work of the Berlin historian and archaeologist Theodore Mommsen, The History of Rome (1854-6), he remarked at the fact that Hannibal, the Carthaginian general who invaded Italy in the second Punic War, had been forced to traverse the perimeter of the western Mediterranean rather than cross the narrow Sicilian channel because the Roman Navy commanded the seas. He was struck by the enormous impact which Roman sea power exerted simply by its existence. He wondered perhaps if sea power had an influence on historical events far beyond the immediate impact of battles won or lost (Mahan, From Sail to Steam, Recollections of Naval Life, pp. 276-7).

What Starr fails to mention is that Mahan frankly explained to a publisher several years later, “The incident is to myself interesting because I attribute any success not to any breadth or thoroughness of historical knowledge but a certain aptitude to seize upon salient features of an era – salient either by action or non-action, by presence or absence”. Here is a candid and sober reminder; in Lima, Mahan undertook what we would now call a “quick study” on historical fact and perhaps on interpretation.

He grasped the single insight that so revolutionized the study of naval history, and he held that that insight came from within. As he put it, “the suggestion that control of the sea was an historical factor which had never been systematically appreciated and expanded. For me . . . the light dawned first on my inner consciousness; I owed it to no other man”. [ Mahan to Roy B. Marston, “Captain Mahan and Our Navy” The Sphere, 17 (June 11, 1905) quoted in Barry M. Gough, “The Influence of History on Mahan”, introductory essay in The Influence of History on Mahan, The Proceedings of a Conference Marking the Centenary of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s “The Influence of Seapower Upon History, 1660-1783” edited by John B. Hattendorf, Naval War College Press, Newport, Rhode Island, 1991, p. 17].

But Mommsen had pointed the way. Mahan’s debt to Mommsen he acknowledges in several letters, and fleetingly in his Introductory (section in the Influence), but it is otherwise conspicuously missing from his book. The preface of Influence is where Mahan discusses, in a few sparse paragraphs, the effects upon Hannibal’s campaign in Italy of Roman mastery of the sea lines of communication. And that’s the end of the matter for him. Mahan’s chief vehicle for illustrating his doctrine of battlefleet primacy is the British Navy at the peak of its power in the 18th and 19th centuries. But because Starr’s forte was classical antiquity, and Mahan had revealed that his inspirational insight arose as a result of reading Mommsen’s account of the Second Punic War, Starr chose to challenge Mahan’s broad-ranging thesis on familiar grounds – or seas. That this quixotic quest reduced his (or his publisher’s) challenge to absurdity is a reflection on the lapse of editorial discrimination in erstwhile respectable academic presses in an effort to compete with the pop-history “made for TV” glut.

Back to Cry Havoc! #45 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc! List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com