This article, originally published in C3i #14, was voted winner of the 2002 Charles S. Roberts Award for Best Historical Article at Origins in August 2003 - DWT

This article, originally published in C3i #14, was voted winner of the 2002 Charles S. Roberts Award for Best Historical Article at Origins in August 2003 - DWT

Long after the "clash of the giants" on the plain of Zama, Scipio Africanus confronted his old adversary, Hannibal again -- this time at Ephesus. But it was not in battle. Just a meeting of two old adversaries, one in exile, the other in disgrace, for purported financial irregularities. Comfortably settled in Hannibal's apartments Scipio Africanus asked the Carthaginian a typical question when military men compare notes.

"Who were the three greatest generals of all time?" Hannibal answered the Roman without hesitation. At the top of his list he placed Alexander the Great -- the Macedonian youth who had conquered Persia, invaded India and seemed on his way to conquest of the known world before he died of "swamp fever." In third place Hannibal named himself. Between himself and Alexander, Hannibal placed Pyrrhus of Epirus.

Modern militarists might be surprised to see Pyrrhus included in a list of the great generals of antiquity. They would probably be shocked to see him ranked above Hannibal -- and flabbergasted that the placement was by the by the great Carthaginian himself.

Pyrrhus, one of the ancient world's most esteemed generals has been overshadowed by a phrase, "Pyrrhic victory," denoting a tactical victory so debilitating to the victor that it amounts to a strategic defeat.

But Hannibal had good reasons for his choice. "He (Pyrrhus) was the first to teach the art of laying out a camp. Besides that no one has ever shown nicer judgment in choosing his ground, or in disposing his forces. He also had the art of winning men to his side; so that the Italian people preferred the overlordship of a foreign king to that of the Roman people."

Early Life

Early Life

Pyrrhus was born in about 318 BC, the heir to the throne of Epirus, a small kingdom in modern Yugoslavia. His childhood was not typical. A few months after his birth an internal dynastic struggle led to his father's assassination. The infant Pyrrhus's life was declared forfeit. So, still in diapers, he found himself a fugitive. Retainers carried him across a roaring river in the dead of night to the relative safety of the court of the king of Illyria.

When Pyrrhus was 12, the Illyrian king Glaucias invaded and conquered Epirus. Pyrrhus was placed on his father's throne and settled down to the task of governing a kingdom so backward that it still had a Royal Goatherd. Then at 17, Pyrrhus was deposed in a bloodless coup while attending the wedding of one of Glaucias' sons in Illyria.

The coup, a seeming personal disaster, had the effect of thrusting him to the forefront of the politics of the Greek- speaking world. The Hellenistic world had been in political turmoil since Alexander's death in 323 BC. Alexander's demise had led to a quarter century of strife and warfare as his chief generals (the Diadochi) contended for control of pieces of his once vast empire. As the climax drew closer, the deposed Pyrrhus attached himself to Demetrius I Poliocretes (the besieger), his brother-in-law. Demetrius was also the son of Antigonus I, one of Alexander's better generals. Antigonus, nearly 80, controlled most of modern Turkey and Greece with his power extending into the Balkans.

Assigned command of a cavalry contingent, Pyrrhus fought with Antigonus at Ipsus in 301. Though Antigonus lost the battle to Seleucus, Lysimachus and Cassander and was slain, Pyrrhus gained a reputation as a tactical genius when the cavalry unit he commanded completely annihilated the opposing force.

Demetrius and Pyrrhus escaped. The latter was set up over a few Greek cities by his brother in law, while Demetrius worked on the reconquest of Greece and Macedon. Then in 300, Pyrrhus was sent as a hostage to seal a treaty between Demetrius and Ptolemy I, another of Alexander's old generals, and now master of Egypt.

While in Egypt, Pyrrhus became one of Ptolemy's favorites. A story is told that, when asked who might someday succeed Alexander as the world's ranking military genius, Ptolemy put his arm around Pyrrhus and said "Perhaps this young man here." Pyrrhus was wed to one of Ptolemy's step-daughters and in 297 BC, with a considerable assist from his father-in-law, regained the throne of Epirus for the second and last time.

Ruler and General

Ruler and General

Having been exposed to the rest of the world, Pyrrhus endeavored to make Epirus more than a mere backward kingdom. For the next sixteen years he never missed a campaign season. Conquering in every direction, he defeated every army he encountered -- including one, under Demetrius, composed of Macedonian phalanxes -- heretofore thought invincible.

But Pyrrhus suffered from a fatal flaw. He lacked persistence. And rarely consolidated what he had conquered. As a result, his victories were fleeting, his conquests temporary. Annexing a territory in the east, he would lose it the next season while campaigning in the west. Demetrius' father Antigonus compared Pyrrhus to a dice player who consistently rolls sevens but doesn't know how to use them.

Pyrrhus also advanced the military art. As Hannibal pointed out, it was Pyrhus who first developed the fortified encampment the Romans were either to borrow or develop independently. He wrote several commentaries on strategy and tactics. In fact he was obsessed with military affairs. At a banquet, after a concert had been performed by two flute players, Python and Casphisias, he was asked which he preferred. "Polyperchon is a good general," he answered. He hadn't been listening. When one of his sons asked him to which of his children Pyrrhus would leave the throne, he replied "To him that has the sharpest sword."

His men loved him. They called him "Eagle" because, they claimed, with him at their head they soared. He returned the compliment, calling them his wings, without which he could not fly. He also lacked the streak of despotism and cruelty common to many kings and commanders of the era. When two men were hauled before him for having made some aspersions on his character while drunk, he asked them if they had said it. "Yes," answered one of them, "All of it, king, and we would have said worse if we had had more wine." Pyrrhus only laughed and ordered them released.

Similarly, when encouraged to banish a detractor named Ambracio, who had been speaking harshly against him, he dismissed the idea. "Let him speak against me here, where there are only a few to listen, than banish him so he can tell the whole world."

Italy Calls

Italy Calls

Then in 280 BC, the city of Tarentum appealed to him for aid against a new and unwelcome power to the north -- Rome.

Collectively southern Italy and Sicily were known as Magna Graecia because of the large number of Greek colonies established there by various city-states since the 6th Century BC. The region was Greek in character, language and culture, not Latin or Italian.

The most important of the Italian mainland cities was Tarentum (modern day Taranto). The city lay astride an isthmus at the heel of Italy's boot, between a shallow protected bay and a tidal lagoon. The city boasted an almost impregnable fortress. At the time of the appeal to Pyrrhus, Tarentum was larger than Rome. A prosperous port city, Tarentum derived most of its income from a combination of the wool from its hinterland, and the purple dye derived from the murex mussels in its harbor. The port itself was, and still is, the safest and largest on the Italian coast. Through its entrance passed the extremely valuable purple dyed wool and grain from its farmland. Tarentum, like most of the Greek cities, had had only fleeting contact with Rome. But with the Republic's victory in the Third Samnite War, the territory of Rome's subject allies now extended far down in the south, within easy range of some of the Greek cities, Tarentum's holdings among them.

In 282, the Tarantines attacked and destroyed a Roman fleet that had entered the harbor of Thurii. Tarentum argued that the Romans had violated a treaty from the previous century forbidding the presence of Roman warships in the Adriatic. The, when the Senate informed Tarentum, that far from being cowed, they were now in a state of war, Tarentum appealed for outside help to supplement its citizen militia. Envoys were sent to Pyrrhus.

At first reluctant the Epirot king was finally won over by flattery. He also had his own ambitions as well.

Asked by his chief advisor Cineas what he would do if he defeated the Romans, Pyrrhus answered he would take Italy. And after Italy? Sicily. "And after Sicily?" queried Cineas. "Why there is Libya and Carthage," came the answer.

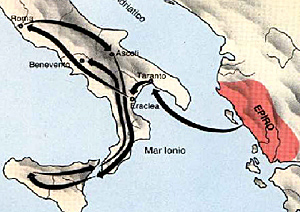

His first act was to dispatch Cineas and a contingent of 3000 troops across the Adriatic to bolster Tarentum's already wavering resolve. Pyrrhus moved his main force in 280. His rival kings, no doubt happy to see him leave, hastened his departure by providing ships, mercenaries, and war elephants (introduced as a result of Alexander's forays into India).

Luck was not with him however, and Pyrrhus was shipwrecked enroute, forced to throw himself overboard from his flagship. In the aftermath he was able to reorganize and gather the bulk of his army and entered Tarentum with 22,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry and 20 of the precious war elephants. No sooner had he entered the city than he realized that the Tarentines were willing to resist the Romans -- until his men had shed their last drop of blood. In anger he shut down all the public entertainments -- bath houses, festivals, theaters and taverns and insisted that the Tarentine militia take up arms. It was the beginning of a constant tension between the Tarentine populace and the king. Meanwhile, the Roman Consul, Publius Valerius Laevinius, had boldly marched south with a consular army of some 40,000 men, pillaging Lucania along the way. When the Romans reached the Gulf of Tarentum, west of the little city of Heraclea, Pyrrhus, who did not want his army besieged inside Tarentum, marched out to meet them.

Pyrrhus' initial tactic was to avoid a battle with the Romans and content himself with positioning his troops along the river Siris to block their progress. In the ensuing respite he could gather allies from the other Greek city states, while harassing Laevinius' supply lines. Furthermore, in the political atmosphere of Magna Graecia, any delay in a Roman attack on Tarentum would be perceived as a moral victory. Laevinius understood this as well. But he had intelligence that the fractious Italian Greek cities were unhappy with Tarentum's leadership and unlikely to send troops unless they had to. He also had no intention of avoiding battle with Pyrrhus. He intended to push the upstart Epirot back into Tarentum and lay siege to the city. All that stood between him and his goal was the river, and the army on the other side.

Laevinius drew up his troops in battle array along the riverbank. Pyrrhus matched his move to oppose the crossing. Though outnumbered 40,000 to 30,000, Pyrrhus drove them back with a furious barrage from his slingers and archers. The Romans withdrew, to the cheers of the Epirots, leaving only pickets along the river. The battle concluded, Pyrrhus returned his forces to their encampment, leaving only a small guard of cavalry to watch the river. He had beaten the Romans, or so he thought. Laevinius' retreat was a mere ruse. The next day a group of horsemen was ordered to splash across the Siris, making as much noise as possible. Pyrrhus' sentries rode off to meet the threat As the guards withdrew, other Roman forces charged the river directly across from Pyrrhus' camp and forded it. Pyrrhus ordered his men into line of battle.

Phalanx vs Maniple

For the first time in in history a Roman general confronted a Greek general. And for the first time in history, the Macedonian phalanx met the Roman legion. It was a study in opposites.

The legion was composed of Roman citizens drawn from Rome and allied cities. They formed a closely coordinated unit requiring much training and drill. The tactical unit of the time was the maniple, which contained two centuries (of about 80 men each). This comparatively high degree of articulation, albeit rudimentary, gave the legion significant advantages in maneuverability in battlefield environments. The maniple came in four types -- all armed with a variety of javelins, pikes and swords. The legion relied tactically on close-in fighting to gain ground while other Roman forces and the cavalry kept the infantry free from harassment.

By contrast, the phalanx required little or no training, particularly in the interior positions since it was simply a massive 16-man deep formation. The phalanxer's principal weapon was the sarisssa -- a sixteen foot pike wielded with both hands. The phalanx simply pushed an opposing force off the field. Its great weakness was in its inability to maneuver once started. Further, because it could only turn with difficulty, its flanks were extremely vulnerable. But the phalanx was formidable and combined with cavalry charges, Alexander had used it to defeat every enemy he met.

Pyrrhus also had elephants. A number of military historians (and wargamers) tend to view them as little more than a "gimmick." The reality was that an elephant was a living heavy tank. Except at very close range their hides were essentially impervious to spears and their earth-shaking charges had to have been psychologically unnerving. If their use, or utility, seems questionable, imagine being armed with a short sword and a pilum and facing a charging elephant. Their one drawback, which the Romans were quick to learn and exploit, was that a wounded elephant has no loyalties and will attack anyone near it. Pyrrhus also made an interesting tactical use of elephants. While most doctrine of the era called for their placement in the infantry line, Pyrrhus used his laterally, as part of the cavalry charge.

Pyrrhus also had elephants. A number of military historians (and wargamers) tend to view them as little more than a "gimmick." The reality was that an elephant was a living heavy tank. Except at very close range their hides were essentially impervious to spears and their earth-shaking charges had to have been psychologically unnerving. If their use, or utility, seems questionable, imagine being armed with a short sword and a pilum and facing a charging elephant. Their one drawback, which the Romans were quick to learn and exploit, was that a wounded elephant has no loyalties and will attack anyone near it. Pyrrhus also made an interesting tactical use of elephants. While most doctrine of the era called for their placement in the infantry line, Pyrrhus used his laterally, as part of the cavalry charge.

As the battle began, Pyrrhus rushed forward with his cavalry, hoping to catch the Romans while they were still crossing the river. They were too late. The Roman cavalry, screening the infantry's fording, rode out to meet Pyrrhus' force. In the ensuing melee, Pyrrhus' horse was killed out from underneath him. The shaken king was hustled to the relative safety of the infantry, now fully formed, while his attacker was killed. Pyrrhus exchanged armor with Megacles, one of his companions, and continued to direct the battle from the infantry ranks. The ensuing melee was bitterly contested. One account records that there were seven changes in the tide of the battle as Greek and Roman struggled in hand to hand combat. The battle was nearly lost when Megacles was killed. Thinking Megacles was Pyrrhus the morale of the Greeks plummeted, and the line wavered. Pyrrhus then boarded a horse and rode up and down his line shouting that he lived.

As the battle continued it appeared that Laevinius' longer line of swords and shield would envelop Pyrrhus' phalanxes. But Pyrrhus called for a cavalry charge from the wings. Now the elephants turned the tide of battle for the final time. Charging into and through the Roman cavalry, they left it in disarray (mostly because the horses broke at the sight, smell and sound of the beasts). With the Roman screening force broken on both sides, the elephants crashed into the infantry's flanks. Simultaneously, the Greek phalanxes drove forward and pushed the legion back to the river. A general slaughter was averted when a Roman legionnaire named Municius jumped from the line and sliced off an elephant's trunk. In addition to proving that the creatures were not supernatural, it had another effect. The Greeks had to deal with a crazed, wounded elephant in their ranks. The Roman's courageous act cost the Greeks the opportunity for pursuit and the remnant of Laevinius' army was able to escape.

Pyrrhus had won at Heraclea, but it was a costly victory. Fifteen thousands Romans were killed, while thirteen thousand Greeks lay on the battlefield.

March on Rome

Having defeated the only consular army in front of him, Pyrrhus marched on Rome. Flocking to him came the Samnites, and the Lucanians, Italians with no love of Rome. Lacking a siege train, Pyrrhus could not hope to take the city. So, when a mere thirty-seven miles from the Servilian walls, he sent Cineas as his ambassador to offer the Romans peace terms. All he demanded was a guarantee from the Romans that he would not attack Tarentum. In exchange he offered a return of prisoners without ransom, and his assistance to the Romans for a conquest of the rest of Italy.

The Romans almost accepted. But the proposal was thwarted by the blind ex-censor Appius Claudius Caecus (builder of the Appian Way) who shamed the Romans for their cowardice. In response to his request for an answer, Cineas was told that Rome would never make peace while their enemy was in Italy.

Pyrrhus, in an attempt to win some favor with the Senate, released his prisoners back to Rome on the condition that if the Senate still insisted on war they be returned to him two weeks later.

Pyrrhus, in an attempt to win some favor with the Senate, released his prisoners back to Rome on the condition that if the Senate still insisted on war they be returned to him two weeks later.

When the Senate refused to consider peace, every man returned to Pyrrhus' custody.

The Romans returned Pyrrhus' chivalry not too long afterwards. A letter arrived to the consuls from Pyrrhus' physician with an offer to poison the king in exchange for a reward proportional to the deed. The consuls, Gaius Fabricus and Quintus Aemilius, sent a message to Pyrrhus, along with the physician's letter, advising him of the treachery.

Pyrrhus then executed the physician and released all his prisoners. The Romans, in a characteristic move, released an equal number of Tarentines and Samnites. Then Cineas returned to the city, anticipating a softening in the Roman position. "Go home," the Senate told him, "And then we'll talk."

Battle of Ausculum

The summer after his victory at Heraclea (279 BC), Pyrrhus met the Romans again, this time at Ausculum.

The battle raged for two days. In the first, both armies fought themselves to standstill. The terrain was disadvantageous for Pyrrhus to use either his cavalry or his elephants because of the wooded country and the nearby river. Both armies found themselves engaged in an infantry slugging match where neither could get an advantage.

The second day he gathered his men and advanced in a close and well-ordered body on the Romans gathered on the plain below. Now it was the Roman's turn to stand and fight, and they did. The Roman line faltered and broke opposite from where Pyrrhus was leading his men and where the elephants struck the Roman front. Plutarch's account describes the impact of the elephants in the line "as an eruption of the sea or an earthquake." The Roman's retreated to their camp. On the field lay the bodies of some fifteen thousand men, two-thirds Roman.

In the meantime, the Samnites, anticipating a Pyrrhic defeat, plundered the Greek camp. At the conclusion of the battle, Pyrrhus, who had been wounded by a pilum was congratulated by one of his generals on the victory. Looking about the field he replied "Another victory like this over the Romans and we are undone." Pyrrhus could not replace his losses, but the Romans seemed to have an inexhaustible well of manpower to draw from. A war of attrition could never be won and he knew it. Twice Pyrrhus had defeated Roman armies in Italy, now a new venture offered itself. The Sicilian cities of Syracuse, Agrimentum and Leontini offered him their fealty in exchange for his aid in driving out another upstart city state -- Carthage.

War with Carthage

War with Carthage

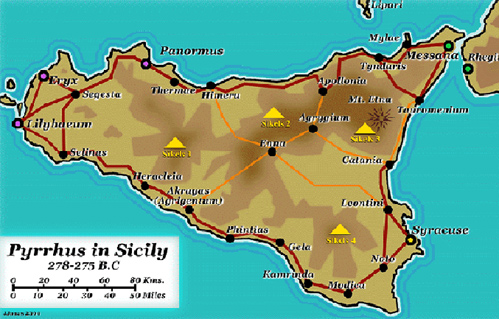

In Sicily Pyrrhus enjoyed his usual unbroken string of military successes over the Carthaginians, but he changed as well. His character and actions became more despotic, his actions more ruthless. He executed one of the men who had invited him to Sicily on trumped up charges of treachery. Finally after three years he was unceremoniously forced to leave. On departure he looked back at the island, and said "Sicily! What a fine arena we are leaving to the Romans and the Carthaginians." The First Punic War was only little more than a decade away.

He reappeared in Tarentum and immediately moved against the Romans who had formed an alliance with the Carthaginians against him. At Beneventum he fought another consular army, this time to a draw. But southern Italy was tired of war and tired of him and the alliance was withdrawn. Pyrrhus left for Epirus, leaving behind a small garrison in Tarentum. The Romans had learned as well. As long as Pyrrhus lived they never made a move against Tarentum.

Pyrrhus' end came in 272 BC while on campaign in Argos. Hard pressed in the high-walled narrow streets of the city, a hostile army without and fierce partisans within, he removed his helmet. A few moments later he was struck on the head by a stone, dislodged by a woman who wanted to get a better view of the legendary commander in action. Dazed and bleeding in the street Pyrrhus was unable to put up any resistance when set upon by an enemy soldier. His head was hacked off by the Argive and taken to the enemy commander Antigonus -- the grandson of Antigonus I.

Pyrrhus was an enigma. A clever and brilliant tactician, he lacked persistence and long-term concentration. As a general he embarked on too many mutually inconsistent projects and oscillated between excessive optimism and gloom. But on the field of battle he had no peer in his time. And to the immortal Hannibal at least, only one other man surpassed Pyrrhus at the ancient art of war.

Back to Cry Havoc! #44 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc! List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com