It is impossible to remember the very first time I ever visited an historic site. I know when I was a toddler my parents, who had moved from Pittsburgh to Richmond, took me to Colonial Williamsburg. But that is just a story to me.

It is impossible to remember the very first time I ever visited an historic site. I know when I was a toddler my parents, who had moved from Pittsburgh to Richmond, took me to Colonial Williamsburg. But that is just a story to me.

Within a couple of years and a stay in Charleston, West Virginia we moved back to Pittsburgh, by which time I had a little sister and, I was four, old enough to carry some memories into adulthood. In the months between coming back to my hometown and starting kindergarten, we took a couple of family vacations. My dad was a traveling salesman and so driving long distances, especially with a couple of small children, was probably not much of break for him. I think that was a big reason why our trips were short ones, an hour or two from home; one was to Erie, my first trip to a beach, and the other was to Ligonier, Pennsylvania, in the Laurel Mountains. It was, and remains, a quaint old town, very popular as a place for vacation homes, especially by Western Pennsylvaniaís wealthiest classes (of which, I can attest, we were not members).

It had two other attractions as well. One was Idlewild Park, and amusement park catering to the youngest children, just the ones whose parents did not want to drive them more than an hour from home. The other was the recently rebuilt Fort Ligonier.

To my four-year-old eyes, it was something right out of the Wild West, or maybe F Troop. It was a classic wooden palisade, with wooden buildings inside, and a museum gift shop that sold Indian-themed toys. I think I got a spear with a rubber tip. The fort reinforced this impression with something I remember very well, traditional dance shows by the first Native Americans I ever saw. In time I grew up, and acquired an adolescentís and then an adultís knowledge and appreciation for the history of the area. Early on, I found out that Fort Ligonier was the last post established on the route of General John Forbes to Fort Duquesne, the smoking ruins of which that tragic and terminally-ill victor first saw from a spot near where I now work. I learned too of Fort Ligonierís repulse of a French attack in October 1758, prior to Forbesí last move on the Forks of the Ohio, and that it held out against another Indian attack five years later during Pontiacís rebellion. Finally,

Fort Ligonier was the place from which Colonel Henri Bouquet, Swiss mercenary and one-time lieutenant to Forbes, lead the force to relieve Pontiacís siege of Fort Pitt, fighting the Battle of Bushy Run on the way. In the rich military history of Western Pennsylvania, Fort Ligonier had a very important role, one that deserves to be remembered.

But for all that, and some extremely happy childhood memories, I never went back to the fort.

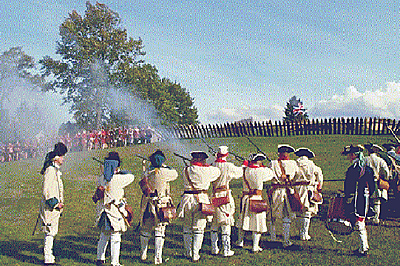

Often enough, I drove past the exits for Ligonier on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, usually on my way to some larger and better-known historical destination. At long last, I did something about that, taking advantage of a vacation day in late June 2003. After thirty-eight years, I finally went back to Fort Ligonier. A lot can happen in that amount of time, and places can change as much as people. But much to my pleasure, Fort Ligonier had not. The grounds and museum are extremely clean and well-maintained, and the fort itself is in an equally fine state of repair. Very rare for any fort, original, restored or reconstructed, the bronze cannons there are polished to such a gleam that they would be the pride of any eighteenth-century artilleryman.

Nearly forty years ago, the fortís reconstruction was undertaken by a private foundation, and lead by the late Charles M. Stotz. Stotz was an architectural historian who was instrumental in the excavation of what remained of Fort Pittís curtain and bastion walls, the preservation of the Blockhouse (a small redoubt that is the only surviving structure of the fort), and who resurrected Western Pennsylvaniaís eighteenth-century heritage of fortification through a series of extremely well-researched drawings. At Ligonier, he applied his rare talents toward building a faithful replica, based on archival research, primary source descriptions, and the archaeology of the site.

Nearly forty years ago, the fortís reconstruction was undertaken by a private foundation, and lead by the late Charles M. Stotz. Stotz was an architectural historian who was instrumental in the excavation of what remained of Fort Pittís curtain and bastion walls, the preservation of the Blockhouse (a small redoubt that is the only surviving structure of the fort), and who resurrected Western Pennsylvaniaís eighteenth-century heritage of fortification through a series of extremely well-researched drawings. At Ligonier, he applied his rare talents toward building a faithful replica, based on archival research, primary source descriptions, and the archaeology of the site.

The results are excellent and Fort Ligonier is as good a reconstruction as one is likely to find. At the same time, where the position or role of a building is a best guess, that is noted too. As standard in many preserved or rebuilt forts, the latter is interpreted through replica interiors, and some rather weak mannequins. But then, this is a very small criticism overall. Fort Ligonier is built on a knoll and follows its contours. Though the main structure is small, this makes it a little confusing to see the overall layout, with four corner bastions, from up close. When it was built, this edifice was surrounded by a much longer ring of palisades, the outer retrenchment. Maybe less than half has been rebuilt, snaking over the southern slope of the hill, where the town of Ligonier has not encroached.

All in all, it should take the average person about an hour to see everything, including a very good small museum. The exhibits there focus, quite naturally, on the eighteenth-century history of the fort, with some unusually interesting maps of the area during the French and Indian War. There are also many relics unearthed by archaeologists there, and contemporary artwork pertaining to the combatants, particular on the British side.

There is also a small portion, a parlor actually, of the home of Arthur St. Clair. Born in Scotland, he served in the British army under James Wolfe, then as a Revolutionary War general and President of the Continental Congress, and after the war was defeated by Indians in what is now Ohio. St. Clair was also the last civil administrator of Fort Ligonier after it was demilitarized in 1766, and upon final retirement settled nearby. Unfortunately the new republic was slow in paying his pension, and though born into wealth, he lost everything to sheriffís sale.

There was one disquieting part of my recent tour, and that was the paucity of other visitors on what was a nearly solitary experience. Especially considering that the fort is open less than half of the year, one wonders how it can remain self-supporting, let alone as lovingly cared for as it is. Fort Ligonier is the only historic site that I have seen with both the eyes of a small child and those of a middle-aged man, several years older in fact than my father was when he took us there. For that

reason, this relatively obscure gem in the Laurel Highlands holds a special place for me, as the site of a happy part of childhood, and where my interest in military history was born. That was something I did not fully realize, until I went back.

There was one disquieting part of my recent tour, and that was the paucity of other visitors on what was a nearly solitary experience. Especially considering that the fort is open less than half of the year, one wonders how it can remain self-supporting, let alone as lovingly cared for as it is. Fort Ligonier is the only historic site that I have seen with both the eyes of a small child and those of a middle-aged man, several years older in fact than my father was when he took us there. For that

reason, this relatively obscure gem in the Laurel Highlands holds a special place for me, as the site of a happy part of childhood, and where my interest in military history was born. That was something I did not fully realize, until I went back.

Getting There

Fort Ligonier is located about fifty miles east of Pittsburgh, in the town of Ligonier, at the intersection of US Route 30 and PA Route 711. Travelers coming from either east or west should take the Pennsylvania Turnpike to the Donegal exit and take Route 711 north about eleven miles to the fort. Alternately, those from Pittsburgh can exit at Irwin and take Route 30 east; as it passes through the Loyalhanna Gorge to Ligonier, it is especially scenic.

The fort is open daily from May 1 to October 1, and admission is $6.50 for adults (less for seniors and children). For more information, see the web site at http://www.fortligonier.org.

Back to Cry Havoc! #43 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc! List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com