Throughout history the need for secrecy has been important. Governments and ordinary people have increasingly sought to secure the delivery of certain messages and important information in a way that allows only the intended recipient access and understanding.

Throughout history the need for secrecy has been important. Governments and ordinary people have increasingly sought to secure the delivery of certain messages and important information in a way that allows only the intended recipient access and understanding.

This need for secrecy brought about the invention and the art of concealment, coding and code making. In return the need for intelligence and information lead to the development of code breaking techniques. These techniques primarily attack a particular weakness that a code or concealment method may have, rendering the sought after information apparent and comprehensible to the assailant.

Evidence of concealing messages can be seen throughout history. These examples in many cases have had considerable effects on the outcome of history, as they may have decided the outcome of battles or the rise or fall of a king or queen.

Steganography

Simply hiding a message or “steganography” can be an effective method by which a message can be delivered without being detected or intercepted by the “enemy”. The effectiveness of steganography however is dependent on the elaborate way in which the message has been concealed, and on the efficiency of enemy intelligence and their persistence in searching and investigating the courier or delivery medium.

Wrapping a message around cigars, as Lee did at Antietam, simply won’t work In the fifth century BC, a Greek exile named Demaratus living in the Persian Empire witnessed the build up and mass of forces by the Persian king Xerxes. Xerxes had intended on conquering the Greeks and Spartans, and was massing his great fleet and forces in preparation for a surprise attack that would catch the Greeks off guard leading to a simple victory. Feelings of patriotism lead Demaratus to warn the Spartans, a task complicated by the fact that he lived in the Persian empire.

Any form of correspondence between him and the Greeks that was intercepted could lead to his execution. What he did to transmit the message was to strip a writing tablet of its wax coating, write on the wood underneath, and then re-wax the tablets. The tablets passed any Persian guards and check points as they were seen to be “Blank”, when they reached Sparta a clever princess worked out the riddle and told them to remove the wax, where lay the message from Demaratus. The Greeks then took action and managed to mobilize and prepare troops in anticipation for the Persian invasion, the subsequent battle was lost by the Persians as they had lost the element of surprise. Their fleet fell into an ambush prepared by the Greeks.

Although steganography may have worked in many cases, its success or failure depends on the message not being discovered. Had the Persian guards removed the wax off the apparently blank tablets the outcome of Xerxes battle with the Greeks would have been different. Due to this obvious weakness in steganography, the development of cryptography became imperative.

Cryptography

Cryptography is a method or technique by which a message may be altered so that it becomes meaningless to anyone else but the intended recipient. This is done primarily in two basic ways, one is to change the position of letters or words within a message, the other is by substituting letters or words by different ones, “Transposition” and “Substitution” respectively.

For transposition to be effective and secure, letters rather than words need to be rearranged, this effectively scrambles the message and produces an anagram.. Transposition could be done for example by writing the order of letters in a word backwards, so that word becomes drow. It is more effective to rearrange the letters in whole sentences or the whole message rather than single words.

If transposition was not limited to words or a certain order the number of different possibilities for rearranging a thirty five letter message rises to 50,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 different distinct rearrangements making the task of working out the correct rearrangement impossible even if all the people on earth were to check a single rearrangement every minute. Transposition can yield a high level of security. However it can produce an increasingly difficult anagram which may become so complicated that even the intended recipient would not be able to decode it. To be effective, transposition needs to follow a simple and straight forward system agreed upon by sender and recipient beforehand.

Ciphers

Substitution is a method that can follow two routes -- either by substituting words for other “Code” words, or by substituting letters within the message by other letters or symbols. Substitution can be simplified by deciding on a specific “Key,” the key is what defines a specific method of substitution, combined with an “algorithm” which specifies the letters or symbols which are used in the substitution in a specific order. When combined and applied to plain text the key and algorithm is what generates the “Cipher”. Working with the plain English alphabet, allowing the algorithm to be any arrangement of the different letter, it is possible to generate more 400,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 different distinct rearrangements of letters and so the same number of different ciphers, thus producing a high level of security, baring in mind that the recipient need only to keep the key safe.

Using the simple substitution method of cryptography, important messages and sensitive information were kept from the prying eyes of enemies for centuries. Any attempt of breaking such encrypted messages was futile, and only led to sleepless nights and no results, some people even started thinking that such encrypted messages were divine, until the 9th Century CE when a Muslim scholar in Baghdad changed the face of cryptography for ever.

Enter the Codebreaker

Enter the Codebreaker

During the period of Abbasid rule (8-13th Centuries CE), learning and research reached unprecedented heights. Caliphs originally gathered vast libraries and paid enormous sums for the translation of books into Arabic. Islam required literacy in Arabic (to read the Quran) and the result was a common tongue that ranged from the Pyrenees to the border of China. People from all levels of the socioeconomic scale were encouraged to learn; books were manually copied and sold in numerous libraries and bookshop. The works of the Greeks, Persians and others were translated and made available to every household. Islamic teachings also make it obligatory for all Muslims to peruse and acquire knowledge of all the sciences with similar and equal degree.

Into this environment came the man destined to be the first scientific “code breaker.” Abu Yusuf Ya’qub ibn Ishaq Al-Kindi better known to the west as Alkindous, was an ethnic Arab descended from the royal Kindah tribe, of southern Arabia. He was born in Kufah Iraq approximately 800, a time of intellectual ferment and growth in the Muslim world. His father was the governor of Kufah as had been his father before him, but Al-Kindi was prevented from that life by Al Ma’mun, the son of Harun Al Rashid and the caliph who founded the “House of Wisdom.” Al-Kindi was appointed chief calligrapher there. Together with Al- Khawarizmi and the Banu Musa he worked on translating Greek texts to Arabic. Although it is thought that Al-Kindi did not participate much in the actual translations, it is more likely that he brushed up on the works of others and may have done some editing and corrections.

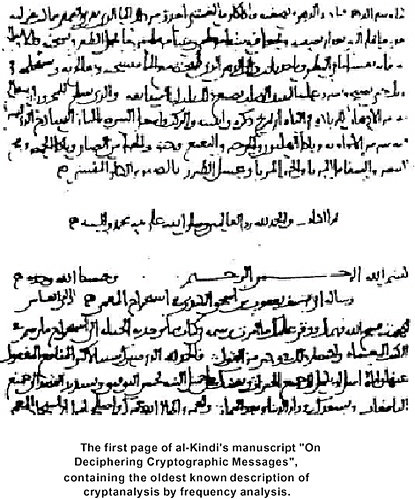

The development of cryptanalysis required high levels of development in three important disciplines: linguistics, statistics and mathematics. Al-Kindi developed personal expertise in all three disciplines and more. Working on Ciphers and encrypted messages obtained from Greek or Roman origins, as well as cryptographic methods employed at the time, Al-Kindi was able to describe cryptanalysis in two paragraphs of his seminal treatise “A Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages”:

The first page of al-Kindi's manuscript "On Deciphering Cryptographic Messages", containing the oldest known description of cryptanalysis by frequency analysis..

- “One way to solve an encrypted message, if we know its language, is to find a different plaintext of the same language long enough to fill one sheet or so, and then we count the occurrences of each letter. We call the most frequently occurring letter the ‘first’, the next most occurring letter the ‘second’, the next most occurring the ‘third’, and so on, until we account for all the different letters in the plaintext sample.

"Then we look at the cipher text we want to solve and we also classify its symbols. We find the most occurring symbol and change it to the form of the ‘first’ letter of the plaintext sample, the next most common symbol is changed to the form of the ‘second’ letter, and so on, until we account for all symbols of the cryptogram we want to solve”

Al-Kindi’s technique, “frequency analysis,” simply involves calculating the percentages of letters of a particular language in plain text, calculating the percentages of letters in the cipher, and then substituting the symbols for the letters who have an equal percentage of occurrences.

A long message would be ideal for this method to work, and there is a caveat in certain cases letters which are used frequently in normal writing and speech may not be used much in a cipher message – either by chance or deliberately to throw off cryptanalysts. Most cryptanalysts also point out that experience, hard work and guessing are usually the keys to breaking a cipher, no matter how complicated. The fact that ciphers could be broken also created the search for new “unbreakable codes” and methods. But as was proven throughout World War II (later successes are still under secrecy seals) even as complicated a system as the German Enigma machine or Japanese Naval Code could be broken by methods that were basically enhancements of the principles laid out by Al-Kindi. Cryptography still remains an important science in today’s civilization, be it for intelligence uses or the privacy of individuals. Cryptanalysis plays a key role as well as governments, individuals, corporations and others seek to unlock the secret communications of others.

References

Al-Ehwany, Ahmad Fouad. “Al-Kindi” in A History of Muslim Philosophy Volume 1. New Delhi: Low Price Publications, 1966. pp. 421-434.

Al-Faruqi, Ismail R. & al-Faruqi, Lois Lamya. Cultural Atlas of Islam. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1986. pp. 305-306.

Ibraham, A. “Al-Kindi: The origins of cryptology: The Arab contributions”, Cryptologia, vol.16, no 2 (April 1992) pp. 97-126.

Prados, John. Combined Fleet Decoded, 1996

Singh, Simon. The Code Book. The Secret History of Codes and Code-Breaking. 1999

Back to Cry Havoc! #42 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc! List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com