Legend has it that Napoleon Bonaparte's Grand Army was destroyed in the retreat from Moscow. There is a certain romance to the image of the French army struggling through blizzards and snowdrifts that has made it enduring. The legend, however compelling and constantly repeated, is pure myth. The truth is that Napoleon's Grand Army had already been shattered and reduced to a third of its original size before it even entered Moscow. His principal adversary and eventual conqueror was a disease caused by an organism with the unlikely name of Rickettsia prowazeki, or as it more commonly known -- typhus fever.

Legend has it that Napoleon Bonaparte's Grand Army was destroyed in the retreat from Moscow. There is a certain romance to the image of the French army struggling through blizzards and snowdrifts that has made it enduring. The legend, however compelling and constantly repeated, is pure myth. The truth is that Napoleon's Grand Army had already been shattered and reduced to a third of its original size before it even entered Moscow. His principal adversary and eventual conqueror was a disease caused by an organism with the unlikely name of Rickettsia prowazeki, or as it more commonly known -- typhus fever.

An Emperor Looks East

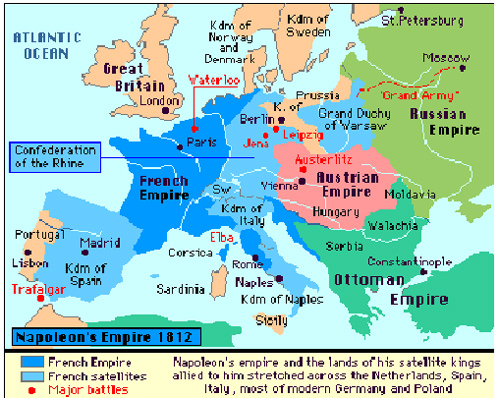

In the Spring of 1812, Napoleon was at the height of his power and his glory. His empire spread eastward to the Russian frontier and the border of Austria, on the north, south, and west it was bounded by the North Sea, the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Two of his brothers wore crowns, Joseph as King of Spain and Jerome as King of Westphalia. His sisters were respectively Grand Duchess of Tuscany; the Princess Borghese; and Queen of Naples. Josephine's son, Eugene was Viceroy of Italy. Napoleon having divorced Josephine had contracted a brilliant marriage with Marie Louise of Austria, daughter of Francis, the last Holy Roman Emperor and first Emperor of Austria.

To this union had been born on March 20, 1811 his first legitimate child and heir, who had immediately been given the title King of Rome. Only two forces stood against him. Britain, only a mere twenty miles across the Channel -- less than a days march away -- was out of his reach, her navy barred the way. Further, the British had recently managed to secure a base in Portugal. Having entrenched themselves behind the strongly fortified lines of Torres Vedras, they were emonstrating the possibility of maintaining and supplying an army by sea. But Britain was still vulnerable by land. The bulk of her trade and wealth derived from her holdings in India. While the trading ships could not be intercepted by sea, the conquest of India itself would deny her the money she needed for war. For Napoleon to take India required either the assistance of Russia, or her defeat and submission.

To this union had been born on March 20, 1811 his first legitimate child and heir, who had immediately been given the title King of Rome. Only two forces stood against him. Britain, only a mere twenty miles across the Channel -- less than a days march away -- was out of his reach, her navy barred the way. Further, the British had recently managed to secure a base in Portugal. Having entrenched themselves behind the strongly fortified lines of Torres Vedras, they were emonstrating the possibility of maintaining and supplying an army by sea. But Britain was still vulnerable by land. The bulk of her trade and wealth derived from her holdings in India. While the trading ships could not be intercepted by sea, the conquest of India itself would deny her the money she needed for war. For Napoleon to take India required either the assistance of Russia, or her defeat and submission.

Such an idea had been proposed in 1807 by Napoleon who envisioned a combined Franco-Russian invasion of India through Turkey and Persia. Both sides had everything to gain by such an alliance, but it came to nothing. The potential allies fell out over a division of spoils before the spoils were even won. Alexander demanded Constantinople and the Dardanelles as the minimum payment for Russia's assistance. Napoleon, who planned a reconquest of the Mediterranean and the Straits of Gibraltar refused to accept a solid Russian entrenchment on his eastern flank. The all too short propitious moment was lost in fruitless argument. In May 1808 Napoleon found himself faced with a Spanish insurrection and in August the British landed an expeditionary force in Portugal, firing the opening shots of the Peninsular War. Meanwhile, Russia became entangled in a war with the Ottoman Empire that would engage her for the next four years.

Friction developed between the two states over Napoleon's establishment of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, which Alexander I saw as a move to restore to the Polish state, something he would not countenance. Another more personal cause of friction existed. In 1810 Napoleon was hunting for a wife to give him an heir and cast his eyes on Alexander's sister Anna, then fifteen year old. The Tsar might have agreed but the Dowager Empress was against the match and forbade it. Napoleon finally ended the negotiations by making a formal offer for the hand of Marie Louise Hapsburg.

Friction developed between the two states over Napoleon's establishment of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, which Alexander I saw as a move to restore to the Polish state, something he would not countenance. Another more personal cause of friction existed. In 1810 Napoleon was hunting for a wife to give him an heir and cast his eyes on Alexander's sister Anna, then fifteen year old. The Tsar might have agreed but the Dowager Empress was against the match and forbade it. Napoleon finally ended the negotiations by making a formal offer for the hand of Marie Louise Hapsburg.

The real cause for the breach between Russia and France was economic. Alexander faced the hostility of his nobles who derived a large part of their income from the sale of timber to maritime nations, in particular England. Alexander's acceptance and joining of Napoleon's Continental System, reinforced by the British blockade of Europe, cut off that source of income. In December 1810, Alexander, under pressure from the nobles, issued an imperial ukase imposing a high tariff on French goods and opening Russian ports to neutral shipping. As Britain controlled the seas, this was the equivalent of permitting unrestricted trade with the principal enemy of France. This was, for Napoleon, the final indignity.

Onward to Russia

From August 1811 onward, Napoleon made preparation for a march eastward. In January 1812 he stripped Spain of many seasoned troops to reinforce the gathering army. He commonly spoke of the common venture as "the Polish War" in which France was to appear as the savior of a Poland enslaved by Russia. But to his troops he made it clear what his real intentions were: "the peace which we shall include...will terminate the fatal influence which Russia for fifty years has exercised in Europe." To his Ambassador to Russia, Armand de Caulaincourt, he said "I have come to finish once and for all with the colossus of the barbarian North."

In March 1812, Napoleon induced Prussia and Austria to sign agreements providing troops. In April he offered a peace treaty to Britain, but was rebuffed. Alexander ended the Turkish War and brought Sweden to his side by promising help against Norway.

Napoleon's armies assembled in cantonments which stretched across Europe from northern Germany to Italy and, in June 1812, started their concentration in East Germany. The force numbered 368,000 infantry, 80,000 cavalry, 1,100 artillery pieces and a reserve of 100,000 men. During the campaign reinforcements brought the total of troops to well over 600,000. For the first time in his career Napoleon had an overwhelming numerical majority against an opponent as the Russian army numbered slightly less than 250,000.

Napoleon's central strike force, or task army, with which he planned to take Russia, numbered 265,000 men. This component force included the Imperial Guard and Ney's crack Third Corps, as well as other units with which Napoleon had established his fame. A mere 90,000 would enter Moscow.

At first everything went well. The summer, abnormally hot and dry allowed the force to march quickly over the easy roads. In east Germany the slower moving supply columns kept slightly ahead of the main force. Food was abundant and the health of the troops uniformly good. Military hospitals had been set up in Magdeburg, Erfurt, Posen and Berlin but there was little demand for their services. Napoleon had acquired a considerable knowledge of and fully understood the importance of public health measures. He showed a great interest in Edward Jenner's discovery of vaccination against smallpox. He had his own son vaccinated when eight weeks old and encouraged a campaign for the vaccination of children and army recruits. The French army's medical and sanitary arrangement, brilliantly organized by Baron D J Larry, were the finest in the world. As a result the French army had never suffered a major epidemic during its European campaigns and been more successful then any other army in coping with the common campaign diseases of diarrhea and dysentery.

Poland: A Silent Enemy Arises

Poland: A Silent Enemy Arises

Poland was filthy dirty. The peasants were unwashed, with foul matted hair, they were lousy and flea ridden. Their hovels abounded with insects. The abnormally hot and dry summer had affected the wells; water was hard to come by and thick with organic matter. The supply trains moved to the rear of the fighting forces. Poland's rudimentary roads were either soft with loose dust or rutted from the spring rains, causing the wagons to lag behind and the food to grow scarce. Only the best units were accustomed to long ordered marches; these columns moved in compact military formation; but the greater part of the army dissolved into straggling, undisciplined bands.

Despite stringent orders to the contrary and harsh punishments, this multitude of stragglers were forced by hunger and thirst to pillage the cottages, livestock and fields of the Polish peasantry. Not surprisingly, the Poles did not look on this French rabble as their liberators. The supplies, auxiliary troops and guerrilla fighters upon which Napoleon had counted, failed to materialize. Instead, the eternal pillaging by his half-starved armies led to a sullen hatred by the Poles which was to recoil upon the French during their retreat. Nearly 20,000 horses, twice the number that might fall in a major battle died from lack of water and forage. Hunger- weakness and polluted water produced the common campaign illnesses of dysentery and diarrheal disease.

In Poland new hospitals were established at Danzig, Konigsberg and Thorn, because of rapidly increasing sick rates. Most of these were respiratory illnesses and diphtheria. Then about the time the Niemen was crossed (June 24) there appeared a few cases of a new malady. Men developed high fevers and a blotchy pink rash, and their faces assumed a dusky blue tinge. Many of those affected died very quickly. It was typhus fever.

Typhus Fever

Typhus Fever

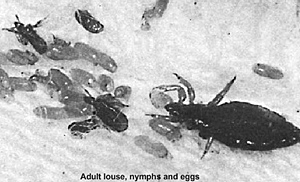

Typhus fever is completely different from typhoid fever despite the similarity of names. The latter is a waterborne or foodborne disease caused by a bacillus. Its principal symptoms are those of enteric fever. Typhus fever, on the other hand, is essentially a disease of filth. The causative organism lies in that class of organisms midway between bacteria and viruses. The organism is carried by lice. Lice are usually found on animals and in the cracks or crannies of old buildings, but they can also infest unwashed bodies and the seams of dirty clothing. They flourish in circumstances where a number of people are herded closely together, wearing the same clothes for prolonged periods and lacking the means of ensuring bodily cleanliness. All these were conditions experienced by field armies everywhere and more heightened by the persistent dislike for regular bathing and changing of clothing in the 19th Century.

For example, cuffs and collars were detachable and changed daily, but the same shirt would be worn for days. Petticoats were worn for several weeks at a time. All the good citizen ever changed on a regular basis was the clothing that could be seen. In other words underneath those exquisite gowns and suits was filthy underwear. In a campaigning army even this abysmal state of hygiene would not be obtainable Typhus had been endemic in Poland and Russia for many years. No one as yet appreciated the relationship between lice and the disease, and were not until H. da la Roche Lima made the discovery in 1911, consequently preventive measures proved impossible). Lack of water and inadequate changes of clothing made bodily cleanliness impossible. Fear of attack caused the men to sleep close together in large groups. The lice crept everywhere, clung to the seams of clothing, infested the hair and bore with them the organism of typhus. Its effect was devastating.

An Army Stricken

At the time of the battle of Ostrovna, in the third week of July, over 80,000 men had perished from sickness or were too ill for duty, 50,000 from the new disease. Typhus alone had robbed Napoleon's strike force of nearly a third of its effective strength and his army was 150 miles from the frontier and Moscow was 300 mile away. The 265,000 men had shrunk to 185,000.

| Losses to the Grand Army's "Strike Force" by Cause | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Event (Date) | Combat Casualties | Disease Casualties | Effectives Remaining |

| Assembly | - | - | 265,000 |

| Battle of Ostrovna (7/21) | 10,000 | 70,000 | 185,000 |

| Battle of Valutino (8/19) | 5,000 | - | 180,000 |

| Depart Smolensk (8/25) | - | 20,000 | 160,000 |

| Prior to Borodino (9/7) | - | 30,000 | 130,000 |

| After Borodino (9/7) | 30,000 | - | 100,000 |

| At Gates of Moscow | - | 10,000 | 90,000 |

| Reinforcements (+15,000) | - | - | 105,000 |

| Moscow (9/14 - 10/19) | - | 10,000 | 95,000 |

| Start of Retreat | - | - | 95,000 |

| Total Losses | 45,000 | 140,000 | - |

| % of 280,000 | 16.1% | 50.0% | 33.9% |

Smolensk was captured in flames on August 17. Two days later Marshal Junot brought the Russians to battle at Valutino, ten miles to the north east of the city, but was unable to stop the Russian retreat, the battle costing another 5000 casualties.

At Smolensk, typhus gained control of the army and when Napoleon marched out on August 25, the task army had shrunk further to 160,000 men. In the fortnight between departure and the battle of Borodino on September 7, an additional 30,000 would be lost to disease. The task force of 265,000 was now only half of its original size by the time the River Moskva had been reached.

At Smolensk, typhus gained control of the army and when Napoleon marched out on August 25, the task army had shrunk further to 160,000 men. In the fortnight between departure and the battle of Borodino on September 7, an additional 30,000 would be lost to disease. The task force of 265,000 was now only half of its original size by the time the River Moskva had been reached.

The Battle of Borodino cost the French an additional 30,000 casualties from battle losses, reducing the Grand Army further.

In the week it took to march to Moscow, another 10,000 were lost to sickness.

Moscow Falls

On September 14 the tattered remnants of the army reduced by battle and disease to 90,000 saw the gilded and multicolored domes of Moscow shining before them. All the church bells were ringing. The gates were shut and the expected deputation to give Napoleon the keys to the city never materialized. The primitive but effective siege engine, the battering ram which had been dragged across the length of Poland was brought forward. The gates were battered down and the army entered to find empty streets and silent houses. On the 15th fires started first in the Bourse then all over the city, set presumably, under orders from Governor Rostoptchin, by liberated criminals who had been furnished with sulphur torches.

Napoleon was convinced that Russia and the Tsar, with Moscow captured, had no alternative but to capitulate. As he waited, in vain, for their surrender, the hot dry summer passed into an abnormally warm autumn. Ambassador de Caulaincourt, the one man in Napoleon's entourage who had experience of a Russian winter, warned Napoleon that his position in the ruined, wasted city would be untenable once the cold weather set in. Napoleon misled by the mild weather, replied that de Caulaincourt was exaggerating.

Reinforcements of 15,000 men joined the army in Moscow during their month-long stay but 10,000 succumbed to disease or wounds during the same period. When Napoleon finally realized that he must quit the city, the army that he led out on October 19 amounted to slightly over 95,000 dirty, half starved and unhealthy men having left behind 10,000 typhus fever patients most of whom died.

The Great Retreat

The Great Retreat

On October 24, Napoleon encountered the Russians at Malojarsolavetz, losing 5000. The way south was barred. The army turned to the north and east back to Smolensk into the teeth of winter. Napoleon arrived with the vanguard on November 8, only to find his reserves under Claude Victor, stricken by typhus fever and the hospitals already crowded with the sick. Napoleon found neither food, nor supplies and left the city on 13 November, leaving over 20,000 sick in the hospitals.

The homeward march became a rout, and the exhausted and sick troops were constantly harassed by the pursuing enemy. The weather grew intensely cold and a large number -- exhausted by sickness and fatigue were frozen. The disastrous crossing of the Beresina cost 40,000 men. The hotly pressed remnants of the French Army passed through Vilna on December 8 dropping off 30,000 who could go no farther. Nearly all had or contracted typhus and in June 1813 only 3000 were still alive.

Another 15,000 had died from cold, famine and disease on the way to Vilna and the army had shrunk to a mere 20,000 sick men. Of Ney's 3rd Corps only 20 men remained. The Grand Army had, for all intents and purposed, ceased to exist.

Napoleon was told of rumors of his death and rushed to Paris on December 6 before news of the disaster to the Army became known there. Murat was left in command, but he proved a broken man. He refused to make a stand at Vilna and on December 10 abandoned the last of the artillery, the baggage and the treasury to the Russians. On December 12 Berthier reported to Napoleon that the Army had ceased to exist; even the Imperial Guard, reduced to less than 500 men, had lost all semblance of a military formation. Ney, fighting a brilliant rearguard action crossed the Niemen on December 14. When the last stragglers had arrived, less than 30,000 men remained of the Grand Army. Only 1000 were ever again fit for duty.

Michel Ney, Marshal of France, wrote to his wife "General Famine and General Winter, rather than the Russian bullets, have conquered the Grand Army" This is the popular opinion but to make the picture complete we should enter the name of General Typhus.

References

Cartwright, Thomas. Disease and History. New York: Thomas Crowell, 1972.

Cloudsley-Thompson, J. Insects & History New York: St. Martin's Press, 1976.

Prinzig, Friedrich. Epidemics Resulting from Wars . Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916.

Zinsser, Hans. Rats, Lice and History. Boston: Little Brown Company, 1963.

French Army: Chart of Losses During the 1812 Campaign (very slow: 276K)

Back to Cry "Havoc!" #41 Table of Contents

Back to Cry "Havoc!" List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com