You can’t go home again.

You can’t go home again.

- -- Thomas Wolfe

The war had slaughtered men and destroyed machines as it continued its devastation – year after year. I had been away from home for three Christmases; others had been away twice that long – and more. For us, memories of home had dimmed, unless there were letters or we heard a song. And, finally, there were rumors that the war was winding down.

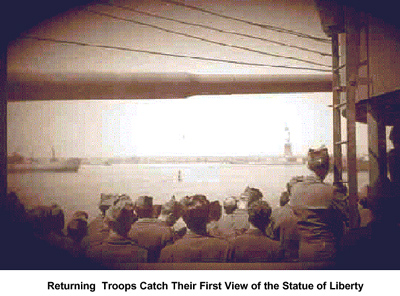

Returning Troops Catch Their First View of the Statue of Liberty

Soldiers learn to discount rumors; we become skeptics. Consequently, there was little reaction when we were told that the Germans had actually surrendered. Even when General Eisenhower made the official confirmation, the reaction was still muted. We felt more numb than elated. Men sat or stood about in small groups and talked quietly while others remained alone as if in shock or deep thought. The years of excitement and boredom, hurrying and waiting, cold and heat, hunger and feast, noise and quiet, terror and calm and of death and life had created an emotional numbness; we were devoid of response.

As the day progressed, those on duty continued their routine while those off duty retired to tents for letter writing, reading or rest – thoughts of home remained unspoken.

One of our more perceptive sergeants collected soap, cigarettes, candy, and such; then drove to a nearby French town and traded for several bottles of wine. When he returned the “happy hour” began. By late afternoon, realization and conversation were in full flow. HOME! FAMILY! AMERICA! THERE WAS A REAL POSSIBILITY THAT WE WOULD BE GOIN’ HOME!

To complete the celebration, a pilot appropriated a crate of signal flare and flew over the French countryside creating a fireworks display. In an attempt to out-do these festivities, a drunken soldier set fire to an abandoned Luftwaffe bomb and ammo dump; as a result, he was blown to bits. The concussion was felt miles around while shrapnel fell among us. Luckily, others were not injured but our euphoria ended; it might be a long time before we would be going home.

Our air base, centrally located near Paris, became an evacuation center for POWs and refugees. This responsibility kept us operational for weeks after the surrender. Russian exiles, POWs and others were flown to Moscow – some, to certain death – while Allied personnel were flown to England and a return to life. VIPs and the lowly passed through but we remained.

Our air base, centrally located near Paris, became an evacuation center for POWs and refugees. This responsibility kept us operational for weeks after the surrender. Russian exiles, POWs and others were flown to Moscow – some, to certain death – while Allied personnel were flown to England and a return to life. VIPs and the lowly passed through but we remained.

Weeks later we were instructed to dismantle and move to the French coast near LeHavre. Rumors were that we would relocate to China for the invasion of Japan; instead, grid-locked military traffic kept us waiting. Finally we boarded a ship and were informed by the crew that our destination was NEW YORK! With this disclosure, we did not complain about being assigned quarters in the lower compartments – almost in the bilge.

The long ocean passage was spent, for the most part, in quarters so crowded that alternate breathing was suggested. We could feel the cold of the North Atlantic on the steel hull as the ship rolled like a water-logged barn door. With seasickness and inadequate latrines, pig sty conditions soon existed; however, we complained less and less.

Early one night the engines stopped – motion ceased – word came down the passageways. “We are anchored off Coney Island and Ferris wheels are turning and lights are bright. You should see it! It’s something you haven’t seen for a long time – a city without blackout!”

One-by-one we stole on deck! Lights were everywhere! They drew us to the side of the ship as though to a magnet! More and more men quietly emerged until a throng crowded the railings, enthralled by the sight. Those were the lights of AMERICA! We stood silently witnessing – beholding – HOME! Our hypnosis ended when a red flare zoomed into the sky and an urgent voice boomed out over the loud speaker, “Everyone will return to quarters immediately – NOW.” We had almost capsized the ship within sight of home.

Back in the ‘bilge quarters’ one man was sobbing uncontrollably. When questioned, he explained that he was from Brooklyn and could see the street lights near the home that sheltered his wife and the three-year-old daughter he had never seen. At sunrise he would see his home. The ship docked before sunrise and, as we filed on deck for breakfast, there were American girls on the nearby wharves as an official greeting committee. Real vocal American Girls!

Camp Kilmer welcomed us with clean clothing, clean water, clean sheets, clean barber-shops and delicious food. Travel orders were hastened and I was on a train to Atlanta the next day. A vendor provided a bacon, lettuce, tomato and mayonnaise sandwich in Richmond where a friendly girl sat opposite me and inquired, “Hi theah soljuh, wheah ah yuh goin’.” – Home!

In Atlanta, I was given a three week furlough. A missed bus connections in Birmingham allowed me time to buy a civilian suit, shirt, tie, socks and wing tipped shoes; a mode of dress I had not worn for three years. We stopped at every crossroads but finally came over the mountain and saw the lights of the Tennessee Valley at 2:00 a.m.

Dad’s attempt to smile, although his emotions contorted his face into a grimace, when he came for me in his old Dodge pickup .We shook hands as two true blue old soldiers and drove home – back to the farm – where I found that my family was also weary of the war. They had endured shortages, rationing, worn-out machinery ad waiting. My mother was as I remembered but my five sisters and two brothers seemed to be more than just three years older; they were now teenagers – almost adults. Home had changed.

A boyhood friend had died early in the Philippines from a sniper’s bullet. When I encountered his father on the street in Cherokee, we shook hands briefly; then he turned and shuffled slowly home. An elderly acquaintance met me on the streets of the county seat and exclaimed, “Hi, Jimmie. I haven’t seen you ‘round lately. Where you been? Must have been stayin’ home?” Attempts to contact old friends from school days were frustrating for they had also gone to the war – some would never return. Others were married – girl friends too – or had found work in places far from home.

While on leave, the Pacific war ended abruptly with the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. There would be no invasion of Japan! A wondrous relief! Upon my return to Atlanta, I was offered re-enlistment. Having enough service points, I declined and was discharged from the Army Air Force. I had had enough of war.

When I returned home, the realization gradually came to me that the time and place of my youth was gone. I had changed; home had changed; mankind had changed and was changing even more. The war and fading memory had isolated me from my origin. Also, reality contradicted my nostalgia – my dreams: home was a legend; its future a vision and its everyday routine, a swiftly passing parade. Wolfe was correct.

McWilliams served as a Sergeant, 9th Airforce, 435 Group Troop Carrier ,78th Sqd

Back to Cry "Havoc!" #41 Table of Contents

Back to Cry "Havoc!" List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com