The stability of many African societies is undermined by a variety of factors, some of which threaten the very survival of their citizens. To the extent that such societies must focus on individual survival, there are few other resources to devote to the well-being of larger communities.

The stability of many African societies is undermined by a variety of factors, some of which threaten the very survival of their citizens. To the extent that such societies must focus on individual survival, there are few other resources to devote to the well-being of larger communities.

It is equally apparent that when national coherence is threatened by a government's inability to preserve order and to deliver some minimum level of services to its citizens, US national interests in that country will not prosper, or will do so with difficulty.

The most prominent characteristic of US foreign policy in Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1990s has been its decline. US regional expenditures in real dollars have been falling, while significant programs, such as those of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), are simply disappearing. These trends are occurring as African states desperately seek development strategies that might help them deal with an almost over-whelming array of problems. And whether we like it or not, nations in Sub-Saharan Africa continue to look to the developed world, particularly to the United States, for inspiration and assistance in such matters.

Disease in Africa is the result of attacks on humans by a vast army of "phantom warriors"--viruses, bacteria, and parasites that have caused epidemic and pandemic diseases with cataclysmic potential.[1] With rapid global connectivity a reality, these warriors are a danger to the United States and to mankind. Previous US security strategies have inadequately addressed this rapidly

emerging threat. To address it in isolation from the human problems that provide the conditions for these warriors to propagate, however, would be an illusive cure.

Disease in Africa is the result of attacks on humans by a vast army of "phantom warriors"--viruses, bacteria, and parasites that have caused epidemic and pandemic diseases with cataclysmic potential.[1] With rapid global connectivity a reality, these warriors are a danger to the United States and to mankind. Previous US security strategies have inadequately addressed this rapidly

emerging threat. To address it in isolation from the human problems that provide the conditions for these warriors to propagate, however, would be an illusive cure.

Unfortunately, many US policymakers seem to lack a holistic view of Sub-Saharan Africa and its problems. Without such a view it is difficult to appreciate how problems associated with economic distress (including localized overpopulation and urbanization), environmental degradation, government incapacity, and disease--all legitimate US national interests in the region--are inextricably linked within states or among tribal groups that extend across several states.

Remediation can succeed only if managed systemically in the region or its sub-regions by all participating US agencies, a daunting task under the best of conditions. Developing strategies to coordinate US efforts in the region should be well within the capabilities of US policymakers. But strategies that lack a rough balance among ends, ways, and means have little chance for success.

The ends in this case--our strategic objectives--are relatively clear, especially when compared to the ways and means to attain them. This article looks at the set of problems described above--solutions to which are in the best interests of the people of the region, the United States, and other nations--and proposes some strategic ways and means that could add coherence to US policies in Sub-Saharan Africa.

A Department Of Defense Role?

The United States has the resources and the ability to address many of the most severe problems in Sub-Saharan Africa. To date, however, attributes that should characterize the world's remaining superpower-- leadership and vision--have been missing from the process.

Consequently, different US agencies deal with discrete aspects of the problems cited above, frequently leaving both the donor and recipients of assistance frustrated by the results.

While few would contend that the Department of Defense is the only, or even the most appropriate, US government agency to solve African problems, it can play an enormously beneficial role when focused on specific aspects of an existing strategy for the region. DOD programs in Africa historically have been modest in scope, but they, too, have been scaled back in the wake of post-Cold War military downsizing and budget cuts. Even so, recent US operations in the region, such as military medical assistance missions, have greatly benefited Africans and significantly advanced US interests. Despite the successes, however, these efforts have fallen far short of their potential. DOD activities in foreign countries are directed by US regional commands--military organizations commanded by senior generals who are responsible for supporting national security strategy over vast areas of the earth's surface. It is relevant to the thesis of this article to note that responsibility for DOD activity in Africa is divided among several such commands.

The headquarters of these commands are staffed by competent, dedicated professionals. However, except in times of crisis, African issues are not of primary interest to any of the regional commanders. This circum-stance produces policies toward African countries that appear to be inconsistent and haphazard, driven more by convenience, crises, and the clout of local US diplomats than by any integrated regional strategy.

The headquarters of these commands are staffed by competent, dedicated professionals. However, except in times of crisis, African issues are not of primary interest to any of the regional commanders. This circum-stance produces policies toward African countries that appear to be inconsistent and haphazard, driven more by convenience, crises, and the clout of local US diplomats than by any integrated regional strategy.

Were such an overarching long-term regional plan to exist, what sort of DOD activities could it embrace? It assuredly would not include significant increases in funding or material for African armies. US troops are not currently based in Africa, a situation not likely to change. Military medical missions in the form of MEDFLAG exercises, however, have supported a wide array of medical activities in Sub-Saharan Africa. The medical missions have proven to be political, strategic, and operational successes.[2] They remain the single best means presently available for conducting the integrated diplomatic and defense strategy that is needed today to advance or defend US national interests in Africa. The exercises could become integral parts of US policy in the region.

The absence of an integrated US policy in Sub-Saharan Africa creates a paradox. Recent history suggests that US policymakers will not resist domestic and international pressures to intervene in African humanitarian emergencies; acceding to such pressure could commit forces on a scale that could significantly impair US ability to respond to major crises elsewhere in the world.[3] Conversely, the ability to intervene early in an impending crisis could preclude the need for substantial force to restore peace--or at least to prevent the spread of the instability to adjacent states. In developing appro-priate policies toward Sub-Saharan Africa, we essentially face the choice of paying a little now or a lot later.

Causes of Regional Health Problems

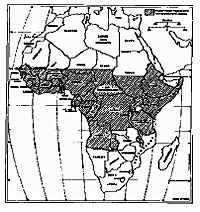

Most of the common threats to stability in Africa can be grouped into four general categories: economic distress, including localized overpopulation and urbani-zation; environmental degradation; government incapacity; and disease. These categories relate to one another in ways that tend to produce a synergy of negative effects.

Remediation efforts must deal with both the causes and the consequences of health problems in the region.

Overpopulation and Urbanization

Overpopulation and Urbanization

Stability in many parts of Africa is threatened by poverty, rapid population growth, and urbanization. During the last 25 years, annual growth rates of 2.5 to 3.5 percent have caused the population of Sub-Saharan Af-rica to double; at the current rate of increase it will double again in 25 years.[4] An increase of this magnitude in such a short time indicates an escalating proportion of children in the population, and thus an increased burden on those who must care for them and on the social services needed to support them.[5] Population growth contributes to migrations to urban areas, particularly by adult males, seeking the pleasures reputedly afforded by urban life and hoping to find employment to supplement family income.

And while national economies in Africa have been unable to provide anywhere near the employment sufficient to satisfy the needs of urban job-seekers, the growth of urban populations continues. In 1965 only 14 percent of Africa's population was urban; by 1990 it was 29 percent. It may be 50 percent by 2020.[6]

The growth of urban population is accompanied by increasing poverty. The World Bank estimates that between 1985 and 2000, the number of persons living in destitution will rise from 185 million to 265 million.[7] A very high proportion of these could be Africans. One source warns that "rapid population growth threatens population stability and may contribute to high and increasing levels of child abandonment, juvenile delinquency, chronic and growing unemployment, petty thievery, organized banditry, food riots, separatist movements, communal massacres, revolutionary actions, and counterrevolutionary coups."[8]

Many analysts have noted that rapid population growth severely impedes the rate of economic development otherwise attainable. Such growth also stresses the environment in ways that threaten longer-term potential for food production, through cultivation of marginal lands and overgrazing. These contribute to desertification, deforestation, and soil erosion, with consequent depletion of soil nutrients, pollution of water, and rapid siltation of reservoirs. Most African nations are not in a position to maintain the infrastructure needed to safeguard the environment or adequately support human needs. Between 1974 and 1994, the subcontinent recorded a 12 percent decline in food production, making it the world's only region of such size unable to feed itself.[9]

The impoverishment of African societies results in another unfortunate situation: many of the most gifted Africans despair of conditions in their societies and emigrate to apply their skills in developed countries. This drains Africa of many of its best engineers, managers, and medical professionals. One result is African societies which lack the basic services taken for granted in developed countries, especially health care.[10] This situation could be reversed only if talented African professionals were provided sufficient incentive to stay in their countries of origin, and more national resources were devoted to basic health care.[11]

The Fouled Environment

Air, water, and land pollution are increasing throughout rural and urban Africa at an alarming rate. Between 1990 and 1994, heavy use of wood and charcoal for heating and cooking and the predominance of sub-standard industrial equipment and vehicles without emission control systems increased the region's contribution to global carbon dioxide emissions from 2 percent to 19 percent.[12] Air pollution significantly exacerbates existing health problems; high rates of pulmonary disease peak during the cold season, when airborne particulates are at a high level and Africans heat poorly ventilated homes with charcoal.

African woodlands are disappearing to meet the demand for fuel in urban areas, while at the same time very few African countries are committed to reforestation. The long-term implications for the ecology--in Africa and elsewhere--are disturbing. Improper disposal of solid and toxic wastes in and around urban areas is routine. Refuse that is both toxic and infectious is commonly dumped along roadways and into waterways. Water sources are routinely contaminated by typhoid, cholera, and organisms causing diarrhea and dysentery. These preventable diseases are the greatest threats associated with humanitarian disasters and mass refugees.

In some areas, unwise use of pesticides and artificial fertilizers (employed in efforts to increase yields of commercial crops) has created a hazard to human health. The extent of this problem is difficult to measure empirically, but emphasis on development at any cost and lack of effective regulation suggest that the problem is likely to get worse before it improves. Lack of potable water is also a serious health threat, particularly in regions that experience prolonged dry seasons or that are located downstream from countries that have built dams on major rivers. In countries for which statistics are available, ready access to water has declined since the 1970s.[13] African countries have placed little emphasis on water purification.

With the increasing pollution (primarily from human waste), serious health care crises are routine and naturally result in epidemic outbreaks. These, in turn, erode the fragile health care infrastructure of African countries and overwhelm the limited available health care resources. The end result is crisis management in health care, which leaves little energy and few resources for attacking the sources of the problems. Availability of water is not the real problem. The issue is the effective management of resources, which also is at the core of another key African dilemma: the competence of national decisionmakers.

Illusory Infrastructure

Government services of the type and effectiveness that many in developed nations take for granted, including health care, are rare in Africa. In an era of rising expectations and declining opportunity, this is a destabilizing factor, one that can pose serious threats to existing governments. Absence of basic social services, nepotism and corruption, and lack of instruments for peaceful redress of grievances all promote anger, conflict, and withdrawal.

Since the mid-1980s there has been some change toward free-market economies in Africa, along with increased transparency and representativeness in some governments, which has resulted in improved living conditions in parts of the region. However, even the best such efforts are dwarfed by the gap between available resources and escalating human needs.[14]

African countries also suffer from another problem--poor cooperation among government agencies, and between government agencies and civil society. It is often difficult for African governments to produce needed co-operation between military and police establishments, or between police and health care organizations. And when weak civil societies cannot furnish the "watchdog" interest groups taken for granted in the West, results include slow, poorly coordinated responses to life-threatening emergency situations and much unnecessary suffering. Sometimes this is the result of inept management; more often it is the result of a lack of resources and limited training.

Urbanization, environmental concerns, poverty, and managerial and infrastructure deficiencies in Sub-Saharan Africa all are inextricably linked to one another and to human health. And because they are, any strategy to attack one or more of them, without addressing all of them, is bound to fail to meet its goals. The deep-seated and intractable qualities of each of these problems preclude quick, easy, or cheap solutions to any of them, as the following survey of significant disease threats demonstrates.

Disease Threats: The Phantom Warriors

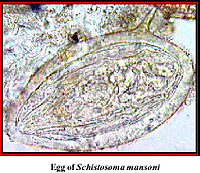

The phantom warriors, scientifically categorized as viruses, bacteria, and parasites, are entities of genetic material that can enter the human body and cause dis-ease. Relatively undetectable by our unenhanced senses, these warriors attack humans and propagate in the form of disease that can reach epidemic and pandemic proportions. The phantom warriors that are afflicting Africans and stalking the human race can be grouped into four main categories:

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and the active symptom complex of infection with HIV called AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

- Ebola-Zaire and other hemorrhagic fever-causing viruses.

- Drug resistant and lethal strains of prevalent diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria.

- Preventable epidemic diseases such as measles and infectious diarrhea caused by typhoid or cholera.

African medicine man -- a key to the acceptance of Western style medicine and a source of local medical

knowledge.

African medicine man -- a key to the acceptance of Western style medicine and a source of local medical

knowledge.

It is difficult to overstate the effects of disease on life in Africa. Of all the world's populations, Africans have the least chance of survival to the age of five. After that age, diseases and the effects of poor diets and other health threats in the environment begin to take a serious toll. If fortunate enough to make it to adulthood, Africans are the least likely of the world's peoples to live beyond the age of 50.[15] The diseases to be discussed are among the primary reasons for this depressing statistic. They also pose a potential threat to US national security.

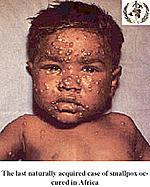

HIV is a pandemic killer without a cure, and viruses such as Ebola-Zaire are merely a plane ride away from the population centers of the developed world. Viruses like Ebola, which are endemic to Africa, have the potential to inflict morbidity and mortality on a scale not seen in the world since the Black Plague epidemics of medieval Europe, which killed a quarter of Europe's population in the 13th and 14th centuries.[16] These diseases are not merely African problems; they present real threats to mankind. They should be taken every bit as seriously as the concern for deliberate use of weapons of mass destruction.

The pandemic HIV, believed to have originated in Africa in the late 1960s, is recognized as universally fatal. Since 1983, when HIV was first documented, more than 16 million men, women, and children in Africa have become infected with the virus, constituting over two thirds of the recorded cases in the world.[17] Hiroshi Nakajima, director-general of the World Health Organization, stated that if the present infection rates continue, by the year 2000 there will be 24 million Sub-Saharan Africans infected with the virus, accounting for nearly half the cases in the world.[18] In Malawi, one eighth of the sexually active population currently is infected.

In Malawi's urban areas, one third of the women attending antenatal clinics carry the virus.[19] The current average life span in Uganda is 59, but by 2005 it may well drop to 32.[20] In the countries located in the "AIDS belt," nearly 25 percent of the urban population is HIV positive.[21]

The epidemic has profound economic and social implications. Economists calculate that by the year 2005, the subcontinent will lose from 15 to 20 percent of its gross domestic product as a direct result of AIDS.[22] Current analysis suggests that the demand for health care in the subcontinent will increase by up to 16 percent over the next six years.[23] Health care workers also are vulnerable to the disease, with infection rates now up to 25 deaths per 1000 in five years. This has resulted in a marked increase in health care worker absenteeism, recently as high as 16 percent.[24] HIV infection of health care providers places a significant constraint on an already inadequate medical infrastructure.

Unlike Western developed countries, in which homosexual intercourse and IV drug use are the primary methods of transmission, heterosexual transmission appears to be the primary cause in Africa.[25] The disease is not confined just to small, marginalized subgroups in the general population in the region. This means there are cultural obstacles and difficult behavioral ramifications inherent in any effort to arrest the spread of the disease.[26]

Ebola-Zaire virus, first discovered in 1976, is the stereotype of the virulent, almost invulnerable "hot-zone" virus. It strikes with great suddenness and lethality, then disappears until the next outbreak. At the very least, in each of the four recorded mass outbreaks, the 90-percent death rate is a stark reminder of the vulnerability of the human species.[27] No one yet knows where the virus resides in nature, how the human epidemics get started, or why they are so rare. In the recorded outbreaks in Zaire and the Sudan, flu-like symptoms typically appeared within three days of infection, and death soon occurred from generalized organ failure preceded by a hemorrhagic diathesis from every orifice.

In its present form, Ebola is unlikely to become a world pandemic disease because of its means of spreading (by infected secretions) and its extreme sensitivity to ultraviolet light. However, given a simple alteration to its genetic structure that provides for more protection during transmission, it could suddenly become a threat of global proportions.

This virus does serve to spotlight the very real horrors that epidemic and pandemic diseases can easily produce in an interconnected world. A genetically altered Ebola virus is one of several viruses found in Africa that could become biological weapons of cataclysmic lethality. Others, like Marburg virus and Congo-Crimean hemorrhagic fever virus, require further investigation and research. These diseases are sufficiently threatening now to warrant an aggressive surveillance program and an expanded capability for isolation and containment of further outbreaks.

In contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa, tuberculosis and malaria are undergoing a resurgence, both in total incidence and in lethality. The emergence of strains highly resistant to current drug therapies, the spread of vectors, declining health care services, and cutbacks in government services as a result of "structural adjustment" are the causes for the renewed lethality of these diseases. The spread of the anopheles mosquito (the vector for malaria) into new areas of Africa also has been associated with a rise in cases and mortality.[28]

Tuberculosis (TB), a disease that has been present from antiquity, remains the world's leading single infectious killer of adults.[29] About 2 billion people, approximately one third of the world's population, are believed to be infected. About 10 percent are at risk for developing the active disease, with one percent dying from it.[30] Initially an infection of the respiratory tract, TB is transmitted by human microdroplets expelled into the air which are inhaled by others. The conditions of crowding and generalized poor health, which make infection more likely, are an obvious correlate of poverty and urbanization. TB in Africa has demonstrated new and highly resistant strains to common drug regimens, making them more contagious and lethal.

Overcrowding and poor sanitation, conditions prevalent in urban Africa, also provide ideal conditions for diseases such as typhoid, cholera, and measles. Both typhoid and cholera appear in situations where drinking water is contaminated with human waste.

Measles, a highly contagious viral infection easily prevented by vaccine, along with infectious diarrhea, appear frequently in mass refugee situations. Combined with dehydration and malnutrition, they are the most common cause of refugee deaths.

A society's confidence in its national government can become strained as a result of the psychological effect of the rising incidence of morbidity and mortality from all these diseases. This is particularly true in Africa, where disease epidemics can be considered evidence of spiritual deficiencies of leaders.[31] Present trends suggest not only that future epidemics in Africa will be ever larger and more virulent, but that national governments will be even less prepared to cope with the problems.

Remediation

Addressing the root causes of regional health problems in Africa should become a higher priority for our national security posture and the corresponding national military strategy. The prospect of pandemic diseases coming to our shores is clearly a "defense of homeland" strategic issue. Ways and means must be sought to achieve the strategic end of adequately defending against these diseases.

MEDFLAG Exercises

A model military program that has dealt successfully with the linked human problems that foster the phantom warriors is the MEDFLAG exercises conducted by the US European Command (USEUCOM) under the direction of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The name MEDFLAG was coined to represent the military medical leadership role in conducting humanitarian and civic assistance in Africa. The exercises were established in 1988 under title 10 funding, and the program was to include up to three exercises per year in three separate Sub-Saharan countries.

USEUCOM was given proponency for this program since most of Sub-Saharan Africa lies within its area of responsibility. Countries are selected for the US military medical interventions by USEUCOM, in coordination with the Department of State and with the approval of the JCS. Since 1988, 19 MEDFLAG exercises have been conducted in 16 countries.

The MEDFLAG exercises are centered around a military-to-military exchange program in which a US joint medical task force (Army, Air Force, and Navy) of about 80 personnel deploys to the selected host nation and conducts an exercise lasting up to three weeks. Exercise activity includes medical training of host-nation personnel, a disaster response exercise, and a combined US and host-nation medical civic action assistance program to treat local populations.

Three MEDFLAGs conducted in 1994 and 1995 achieved a level of sophistication and complexity that established the exercise as one of the best uses of the military element of national power in Sub-Saharan Africa.[32] These three exercises were organized and carried out by a US Army Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) stationed in Germany.

The countries selected for the missions were Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire in West Africa, and Botswana in southern Africa. The basic medical element in each deployment was an Army unit--the MASH--with Air Force and Navy medical personnel attached. NATO allies were invited to participate; the presence of multiple services and of British, Dutch, and German officers made the MEDFLAG organization both a combined and joint task force (CJTF).

Each of the three MEDFLAGs in 1994 and 1995 followed a similar pattern. They were preceded by intense discussions among representatives of US European Command, host-nation political and military decisionmakers, US diplomats, and host-nation health care professionals from the public and private sectors.[33] These consultations determined the interests and particular health care needs of the country and obtained the agreement of all parties to a specific plan. They also clearly identified the expected contributions of all participants.[34]

Upon deployment to the host country, members of the CJTF linked up with their host-nation counterparts to begin activities. MEDFLAG activities were built around a standard format, modified to meet local conditions, and based on two self-evident medical needs of most of the Sub-Saharan African nations: training and treatment. Training included classes for local personnel in a variety of medical, health care, and disaster relief skills, culminating in a large-scale, mass-casualty exercise. Treatment included the delivery of medical, dental, and surgical care to individual citizens, as well as an ambitious immunization program against local disease threats. A less obvious but perhaps more important feature of these exercises was the opportunity they afforded to bring together national and local governments and health care communities in cooperative relationships.

The 1994 and 1995 MEDFLAGs provided services that were immediately obvious to host-nation observers: treatment of thousands of individual citizens and supervised large-scale inoculation programs in areas of ongoing epidemics (yellow fever in Ghana, meningitis in Cote

d'Ivoire). They provided health care training to medical personnel and lay persons in skills that citizens increasingly are demanding from African governments. The mass-casualty exercises were both highly visible "good shows" that people enjoyed, and obvious training to prepare for events that commonly occur in Africa. Collateral benefits included the ability to tailor each intervention to accommodate individual country needs and to test new technical equipment that could enhance US and other national operational and medical care effectiveness.[35] The MEDFLAGs proved to be immensely popular in each country, drawing the enthusiastic attention and involvement of senior political leaders. They also were covered extensively and very sympathetically by local media.[36]

The 1994 and 1995 MEDFLAGs provided services that were immediately obvious to host-nation observers: treatment of thousands of individual citizens and supervised large-scale inoculation programs in areas of ongoing epidemics (yellow fever in Ghana, meningitis in Cote

d'Ivoire). They provided health care training to medical personnel and lay persons in skills that citizens increasingly are demanding from African governments. The mass-casualty exercises were both highly visible "good shows" that people enjoyed, and obvious training to prepare for events that commonly occur in Africa. Collateral benefits included the ability to tailor each intervention to accommodate individual country needs and to test new technical equipment that could enhance US and other national operational and medical care effectiveness.[35] The MEDFLAGs proved to be immensely popular in each country, drawing the enthusiastic attention and involvement of senior political leaders. They also were covered extensively and very sympathetically by local media.[36]

Despite the large number of patients treated and the new skills imparted to host-nation personnel, it is evident that a three-week exercise can have only very limited direct effects on the health care needs of an entire country. However, the real value of a MEDFLAG is much more profound: the exercise serves as a catalyst to initiate or revitalize important long-term domestic and international relationships and programs.

Another important, if somewhat less obvious, aspect of the MEDFLAG program is its portrayal of values appropriate to health care personnel. US participants were expected to display the competence and self-sacrificing dedication which US society expects of the medical profession. By extension, these exercises display an ethic of public service which serves as a challenge for observers to emulate.[37]

MEDFLAGs offer a highly effective means for co-operating with African governments to improve medical services to the local population. In 1994 and 1995, these missions allowed African national governments to demonstrate active interest in the well-being of local communities. With US assistance, the host-nation military and local civic leaders provided unprecedented services to rural populations.[38] Participants also received valuable training in coordinating among local government agencies and in linking the efforts of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and private voluntary organizations (PVOs) to objectives established by local authorities.[39]

This particular outcome markedly improved the ability of the United States and host-nation military medical staffs to plan for cooperative future efforts. MEDFLAGs demonstrated on a national scale what might be achieved by similar cooperative efforts involving entire subregions. US diplomats in Africa recognized that the obvious increase in US and host-nation interactions which resulted from these missions served to strengthen political ties.[40] This should not have been surprising. US military officers with extensive African experience expressed astonishment at the success of military medical operations in providing access to senior decisionmakers in the countries where the exercises had been held. They strongly believe that such operations significantly reduce African suspicions of US regional motives and increase the willingness of African leaders to cooperate with the United States in other ways.[41] In short, MEDFLAGs have proven to be an ideal template for future US military operations, medical or other, in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Some have questioned the wisdom of employing US military forces in large-scale humanitarian relief operations, arguing that such missions degrade the ability of the US military establishment to perform its primary mission: to fight and win the nation's wars.[42] While this argument may have merit when applied to the combat maneuver forces, it manifestly is not true when applied to US medical personnel.

Some have questioned the wisdom of employing US military forces in large-scale humanitarian relief operations, arguing that such missions degrade the ability of the US military establishment to perform its primary mission: to fight and win the nation's wars.[42] While this argument may have merit when applied to the combat maneuver forces, it manifestly is not true when applied to US medical personnel.

Besides providing excellent training for US personnel, each MEDFLAG exercise included many essential individual and collective wartime tasks. MEDFLAGs tested combined and joint task force operations for all levels of US command, from theater level to the small dental and preventive medicine detachments that were attached to the CJTF. As a result of the MEDFLAGs, MASH combat readiness was directly and measurably improved at the individual soldier and unit level. The three missions in Africa in 1994 and 1995 contributed directly to the high quality of the support the MASH provided to US forces that deployed to Bosnia in December 1995.[43]

The United States, its NATO allies, and regional authorities could continue to benefit from a long-range program of recurring MEDFLAG exercises in consonance with a coherent plan to address specific US subregional objectives. Unfortunately, MEDFLAGs like those conducted in 1994 and 1995 have not been repeated.[44] This is largely attributable to the recent preoccupation of EUCOM, the sponsoring command, with requirements in Eastern Europe as well as demands on forces and supplies for the Balkans.

Beyond Direct Intervention

The United States sponsors programs with African nations to conduct research and disease surveillance, but they are few and underfunded. Since 1952, the US Army has maintained an active investigation of malaria in Kenya, which has supported Kenyan education and disease research. The project has provided current field data on the best methods of disease prophylaxsis for soldiers deploying into endemic malarial regions.[45] The lack of US engagement with African nations in this process is puzzling, for Africans--like most people-- are generally very receptive to assistance that improves their health. Few private sector agencies in developed countries have had the vision or resources to establish such programs in Africa.

For minimum protection of the US homeland itself from likely threats, the United States should expand its efforts to include new research centers located in each subregion of Sub-Saharan Africa. Centers must, of course, conduct disease research and education cooperatively with the host nation. Additionally, these programs should mobilize and link existing relevant programs and be expanded to include disease surveillance, isolation, and containment. Disease Research, Surveillance, Isolation, and Containment Centers (DRSICC) could conceivably integrate US efforts from the Department of Defense, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), nongovernmental programs, and private volunteer efforts together with the World Health Organization and indigenous scientists approved by appropriate regional organizations. A cooperative effort at this level would not only directly benefit Africans, but would provide the necessary multinational commitment to disease research and surveillance needed to actively defend against current and future pandemic threats. Africa is the most prolific "petri dish" of human biological catastrophes on earth, and therefore it is the place to initiate, in cooperation with Africans, large-scale research and surveillance to diminish these threats.

The United States itself must develop the line of defense necessary to stay abreast of mutating phantom warriors, a result of the conditions that plague Africa and other regions. A laboratory capability to monitor disease threats could greatly increase the US ability to protect against deliberate use of biological agents as weapons.[46] Containment of the diseases that threaten Africans today, through the development of prophylaxsis and cures, would allow the United States to maintain the scientific edge necessary for effective defensive countermeasure to biological threats from weapons or natural sources.

Prescriptions for Success

African societies suffer from many problems, including severe threats to human health, which adversely affect regional stability. But while the problems and their cures are recognized by US policymakers, there is little agreement over responsibility for addressing them. Some

argue that the United States has no vital interests in Africa, and that taxpayers' dollars should not be spent merely to assuage humanitarian impulses. Experience, however, has shown that such investments can lessen the severity of some local problems while supporting fundamental US interests in the region. US interests in Sub-Saharan Africa should be flexible enough to adapt to subregional conditions. A holistic approach to the four kinds of problems identified in this article should rest on cooperative US and host-nation programs that systematically improve the ability of host nations to manage the problems themselves. The recent increase in "human condition" threats must be addressed first, since concerns for economic growth and government reform are secondary to the struggle for survival. MEDFLAG exercises have provided a good model of how this can be done.

African societies suffer from many problems, including severe threats to human health, which adversely affect regional stability. But while the problems and their cures are recognized by US policymakers, there is little agreement over responsibility for addressing them. Some

argue that the United States has no vital interests in Africa, and that taxpayers' dollars should not be spent merely to assuage humanitarian impulses. Experience, however, has shown that such investments can lessen the severity of some local problems while supporting fundamental US interests in the region. US interests in Sub-Saharan Africa should be flexible enough to adapt to subregional conditions. A holistic approach to the four kinds of problems identified in this article should rest on cooperative US and host-nation programs that systematically improve the ability of host nations to manage the problems themselves. The recent increase in "human condition" threats must be addressed first, since concerns for economic growth and government reform are secondary to the struggle for survival. MEDFLAG exercises have provided a good model of how this can be done.

To encourage the development of an integrated US strategy in Sub-Saharan Africa regarding the spread of infectious diseases, DOD should consider the following initiatives:

- As a matter of "homeland defense," we should increase disease surveillance and research in Africa and elsewhere in the developing world. The basic capability to do so exists in DOD, though it is extremely limited. An expanded capability would include cooperative efforts with African nations to emphasize outbreak isolation and containment. Such an initiative would help African nations to attenuate disease threats while allowing them to build the capabilities to provide their own containment and control programs for the future. Research and surveillance clinics, staffed by US and host-nation personnel, should be established in the east, west, central, and southern regions of the subcontinent. It is worth noting that these activities will afford the US an enhanced capability to deal not only with acts of nature, but also with deliberate uses of biological weapons by a future adversary.

- Increasing US disease surveillance efforts should be tied to an increase in exercises of the scope and capability of the 1994 and 1995 MEDFLAG series. Such exercises should focus on hygiene, public sanitation, disease vector control methods, disaster management, medical expertise for cases of mass refugees, and education and training to improve disease prevention. Medical civic action projects should help the host nation project and stabilize the medical infrastructure and medical care capability within areas of greatest need. MEDFLAGs also can prepare US military units and command echelons for situations such as disaster relief that require rapid responses. A collateral benefit of having worked with and trained African personnel is that the training could facilitate the rapid integration of African medical personnel in disaster relief operations in Africa and elsewhere in the world.

- Although admittedly a more complex and problematic issue, DOD should establish a regional command that can provide a full-time focus on the entire African continent. As noted earlier, the African continental land mass falls under the responsibility of two US military commands (the US European Command and the US Central Command) whose primary focus in each case is elsewhere. Islands surrounding the continent fall under the purview of still other commands. The situation in the Balkans reminds us that the US European Command simply cannot fulfill its obligations in Europe and at the same time devote the required attention to the 38 African countries that are within its area of responsibility. Instituting these recommendations would offer no guarantee that we could avoid complex humanitarian emergencies in Africa. It can reasonably be assumed, however, that the frequency, cost, and magnitude of the ensuing interventions could be reduced, and that indigenous capabilities for assuming responsibility for controlling regional disturbances would be improved. Failure to implement these changes could increase the probability that large and progressively less well prepared US forces will be deployed into the next African humanitarian disaster.

The United States stands at the brink of an era in which, with great vision and minimal additional resources, it can profoundly affect the well-being of a huge area of the world. In the process we just may find a way to defend against a threat that could eradicate mankind. It is clearly in the national interest to do so. History is scathingly unkind to those who fail to rise to such challenges.

NOTES

1. The American Heritage Dictionary in MS Bookshelf de-fines endemic, epidemic, and pandemic as follows. Endemic: "1. Prevalent in or peculiar to a particular locality, region, or people." Epidemic: "1. Spreading rapidly and extensively by infection and affecting many individuals in an area or a population at the same time." Pandemic: "1. Widespread; general. 2. Medicine. Epidemic over a wide geographic area."

2. US European Command, "USEUCOM MEDFLAG Exercises," an unclassified report 25 February 1997, from the EU-COM Surgeon's office, Stuttgart, Germany. This document provides the background and origin of the MEDFLAGs.

3. This subject warrants careful consideration. A more focused DOD Africa program was being crafted in the Office of the Secretary of Defense under the management of Mr. Vince Kern and Dr. Nancy Walker early in 1997. This is a very positive development and should be emulated in a coordinated national-level effort.

4. World Bank, World Development Report 1992 (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1992), pp. 258-59.

5. Some 40 percent of the African population is presently under the age of 15. Yvette Collymore, "Short Shrift for Africa," Africa Report, 39 (November-December 1994), 42-46. Interestingly, a destabilizing factor in many African countries is popular discontent over the lack of educational opportunity for children. Interview with Colonel Dan Henk, 11 April 1997, Carlisle, Pa. Colonel Henk is a cultural anthropologist with extensive African experience. He points out that the problem is compounded in African countries, which produce large numbers of primary and secondary school graduates who cannot find employment in the formal economic sector.

6. Akin L. Mabogunje, "The Environment Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa," Environment, 37 (May 1995), 435.

7. World Bank, World Development Report 1990 (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1990), p. 139. A recent UN report notes that the ten poorest countries in the world are all located in Sub-Saharan Africa. See United Nations, The Progress of Nations 1997, on the Internet at http://www.unicef.org/pon97/.

8. Edd Doerr, "Curbing Population: An Opportunity Missed," USA Today magazine, January 1995, pp. 36-37.

9. "Africa for Africans," The Economist, 7 September 1996, p. 8. See also Leif Roderick Rosenberger, "The Strategic Importance of the World Food Supply," Parameters, 27 (Spring 1997), 84-105.

10. Gerard Piel, "Worldwide Development or Population Explosion: Our Choice," Challenge, 38 (July-August 1995), 13-22. Piel argues that the problem is not overpopulation per se, but the fact that the majority of this population is impoverished with little hope of amelioration in the foreseeable future. The disparity between the "haves" and the "have nots" is expanding globally, and in no place more profoundly than in Africa. This situation further serves to stress the population and creates a sense of disenfranchisement from the national government. Further, it creates the potential for conflict along class, ethnic, or religious lines as people mobilize to compete for diminishing resources.

11. Ironically, a factor in Africa that draws rural people to urban centers is the expectation of better access to health care. Unfortunately, rapid urbanization is occurring at the same time that health care access is diminishing, which fuels popular discontent. Piel argues that to stabilize the world's population at a sustainable level, the industrial revolution must be carried out worldwide. This would require the coherent, large-scale assistance of the developed world. He estimates that the total capital outlay required for such a task would be $19 billion per year, with decrements in that amount as development escalates in the underdeveloped nations. Piel, p. 14.

12. Mabogunje, p. 9.

13. United Nations Development Programme, Environment & Natural Resources Group, The Urban Environment in Developing Countries (New York: United Nations, 1992), p. 29. Another author points out that while agricultural irrigation accounts for nearly 90 percent of the total consumption of fresh water, only 37 percent of the water used for irrigation is actually absorbed by crops. The rest is lost to evaporation, seepage, or runoff. The value of fresh water continues to rise. Kent Hughes Butts, "The Strategic Importance of Water," Parameters, 27 (Spring 1997), 65-83.

14. "Africa for Africans," The Economist, p. 17. National priorities warrant continued rethinking. For instance, nearly all the current governments of Sub-Saharan Africa continue to spend more of their gross domestic product (GDP) per annum on defense than they do on health care.

15. Keith Richburg, "The Same Old Excuses," U.S. News and World Report, 3 February 1997, pp. 36-38.

16. Geoffrey Cowley et al., "Outbreak of Fear," Newsweek, 22 May 1995, pp. 48-55.

17. John C. Caldwell and Pat Caldwell, "The African AIDS Epidemic," Scientific American, 274 (March 1996), 62-68.

18. "Africa for Africans," The Economist, pp. 1-18.

19. Ibid., p. 16.

20. Ibid.

21. Caldwell and Caldwell, p. 64.

22. Ibid.

23. "Impact of HIV on the delivery of health care in Sub-Saharan Africa: A tale of secrecy and inertia," The Lancet, 27 May 1995, pp. 1315-17.

24. Ibid., p. 1316.

25. Caldwell and Caldwell, p. 62.

26. Ibid., p. 68. These authors believe that the best chances for combating AIDS everywhere lie in targeting education and prevention programs at high-risk groups. The number of AIDS cases has essentially grown unabated despite educational and financial assistance by the United Nations, nongovernmental organizations, and private voluntary organizations. New approaches and additional efforts are needed.

27. Shannon Brownlee et al., "Horror in the Hot Zone," U.S. News and World Report, 22 May 1995, pp. 57-60.

28. "Africa for Africans," The Economist, p. 15.

29. Lynn W. Kitchen, "AIDS Revisited," CSlS Africa Notes, No. l46 (March 1993).

30. Ibid., p. 2.

31. Henk interview, 11 April 1997.

32. These three MEDFLAGs were organized and conducted by the 212th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) headquartered in Wiesbaden, Germany.

33. The latter included local community leaders and nongovernmental and private voluntary organizations (NGOs/PVOs).

34. An important objective of the coordination was to reas-sure host-country leaders that the MEDFLAG exercise was to be a genuine partnership with no hidden agenda.

35. For example, at the host nation's request, the Botswana MEDFLAG included a US veterinary team to assess the health of local cattle herds and the sanitation of meat processing facilities. The Cote d'Ivoire MEDFLAG featured the use of "telemedicine" for medical and surgical care assistance provided via near-real-time video link through a satellite connection to specialists in Landstuhl Regional Army Medical Center in Germany.

36. For instance, the Botswana National Press characterized the 1995 MEDFLAG as a "monumental program for success."

37. Henk interview, 11 April 1997. Colonel Henk provides an anecdote that illustrates the importance of this MEDFLAG service. In the late 1980s, missionary medical personnel in southern Zaire began to encounter numbers of local citizens seeking care for complications associated with appendectomies. They were puzzled, because appendicitis is relatively rare in the region. However, informal investigation revealed that poorly paid government doctors were falsely diagnosing this malady in order to convince their countrymen to undergo an expensive--but unnecessary--operation.

38. This advantage was not lost on host-nation leaders. In his farewell address to the 1994 MEDFLAG, the Ghanaian Vice President publicly requested another at the earliest opportunity.

39. Interestingly, as the commander of the MEDFLAG in both Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire, I noted that a number of the participating PVO personnel acknowledged having changed their previous negative attitudes about military establishments as a result of the exercise.

40. The US Ambassador to Ghana in 1994, the Honorable Kenneth Brown, stated that the MEDFLAG mission to Ghana was the best example of US engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa that he had encountered in his many years of Foreign Service experience in the region.

41. Henk interview, 11 April 1997. Colonel Henk had served as a US Defense Attaché in Botswana, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Also, Lieutenant Colonel Anthony Marley (USA Ret.), interview by author, 9 April 1997, Carlisle, Pa. In a colorful career, Marley served in Cameroon, Liberia, and as a US negotiator mediating among competing sides in the civil war in Rwanda (1993-1994).

42. Charles J. Dunlap, Jr., "The Military Coup of 2012," Parameters, 22 (Winter 1992-93), 2-20. Dunlop develops a hypothetical scenario that proposes the most graphic potential outcome of US military readiness degradation due to numerous humanitarian operations: a military coup.

43. This is the author's opinion having served as the commander of the 212th MASH from July 1993 to July 1995. Follow-up discussions with several of the officers who served on multiple MEDFLAGs with the 212th and subsequently deployed to Bosnia have validated this opinion.

44. Much smaller-scale medical exercises conducted in Africa by EUCOM units and special operations forces have continued. However, while of benefit to recipient countries, programming of these exercises does not fit a comprehensive, long-range US national plan. Nor do these exercises offer the substantial benefits evident in the 1994 and 1995 MEDFLAGs.

45. Other developed nations, the World Health Organization, some private foundations, and some academic institutions maintain similar small-scale programs, but these efforts are also underfunded, not mutually supporting, and fall far short of the requirement necessary to meet the current African disease threats.

46. This is particularly true since biological weapon effectiveness is contingent upon stability of the contagion, easy transmissibility to the human host, and rapid morbidity and mortality, all conditions which currently exist in Africa.

Back to Cry Havoc #37 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com