![]() It was a dark and stormy night, thunder rolled down the valley like the guns of Antietam, and they were stuck in this hell-hole of a stage station with its leaky roof and cold, boiled turnip stew with pieces of unidentifiable; but suspicious, meat embedded in congealed fat warmed over by the station manager’s wife for her unexpected supper guests while the inept hired hand tried to replace the strap-iron on a broken doubletree

and the Indian boy ran through the night after the horse that had fled in terror when the harness broke while climbing up the cut in front of the home station. The driving rain that marched down the canyon ahead of the rolling thunder ran down the walls of their shelter beside the stable, making rivulets in the clay plaster that held the stones of the wall together and partially obscured their raw outlines.

It was a dark and stormy night, thunder rolled down the valley like the guns of Antietam, and they were stuck in this hell-hole of a stage station with its leaky roof and cold, boiled turnip stew with pieces of unidentifiable; but suspicious, meat embedded in congealed fat warmed over by the station manager’s wife for her unexpected supper guests while the inept hired hand tried to replace the strap-iron on a broken doubletree

and the Indian boy ran through the night after the horse that had fled in terror when the harness broke while climbing up the cut in front of the home station. The driving rain that marched down the canyon ahead of the rolling thunder ran down the walls of their shelter beside the stable, making rivulets in the clay plaster that held the stones of the wall together and partially obscured their raw outlines.

Suddenly, a woman screamed in terror in the next room and a shot rang out, competing with the thunder but with a more urgent tone. Drawing his .44 Colt and pulling back the hammer, he snuffed the lamp so that he wouldn’t present a silhouette when he opened the door, and stepped out into the rain to get to the room where the blond lady who had joined the stage at Las Animas had screamed-either a school marm from Kansas City on her way to Trinidad or a fancy woman from St. Louis on her way to Santa Fe to start life over as a virgin-she had been too busy hanging onto the seat to talk much during the day’s stage ride and he couldn’t tell.

Smoky orange light from the badly trimmed wick of the lamp was streaming into the deluge from her open door and she was cringing in a muddy corner of the room-definitely a school marm-while trying to reload the tiny pearl-handled gun she was holding. A rivulet of water was starting to cut a channel which would become a waterfall through the hole that her shot had made in the sod roof. As the old soldier slipped sideways through the door and out of the light, she pointed at the opening and stammered-Indians!

Cautiously peering into the storm, he discovered that she was right-and the Indian had dropped the halter of the horse when her shot frightened him. It would take the boy another hour to catch the terrified animal and bring it back to complete the augmented team that would be needed to pull the stage through the deepening mud when they resumed their interrupted journey. Snorting in disgust, the gray veteran let the hammer down on an empty chamber, re-holstered his colt, went back into the room he had just left, and picked up his poker hand.

Seeking Truth Behind the Story

So! how does this piece of 19th century meller-drammer relate to a modern archaeological dig in the Purgaroire Valley? The outline fits the known historical facts and the archaeological results-and, its a lot more exciting (the details are pure fiction)! Testing an avocation which had attracted me in my youth, but been rejected in favor of a more financially rewarding career, I joined the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs’ summer field course in archaeology-which was a dig at the Bent Canyon Stage Station in a side canyon of the Purgatoire in the hottest August in memory.

A number of ranchers were saved from having to admit that they couldn’t make a living running cattle on the north side of the Purgatoire in the economic conditions of the latter half of the 20th century when a large part of the area was purchased by the US government and turned into a military maneuver area-an isolated wide-open-space where the army can practice driving tanks and firing blank ammo. To preserve the archaeological record of the area, the army hires survey teams to locate sites of human activity-ranging from Paleoindian to Hispanic and Anglo farmers and ranchers-and dig/record significant sites.

One of those sites was the Bent Canyon stage station. The Barlow and Sanderson stage line provided a connection from the railroad near Las Animas to the town of Trinidad near the New Mexico border between 1871 and 1876-the stage route closed when the railroad reached the vicinity of Trinidad. The only “home” station of the line was at the head of Bent Canyon. It provided a change of horses and food, normally lunch-hence supper was “warmed-over”, for the travelers.

The station was located on a working ranch. Both Anglo and Hispanic families in the area were known to “acquire” Indian children as house servants. Some have called the Indian children slaves; but in this period after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery there is no record of mistreatment. There is a record of the “slaves” receiving the same formal education as other children in the family. The children of relatives, or neighbors were often taken into a relatively wealthy household for periods when their parents could not feed them. This accounts for the Indian boy in the meller-drammer.

The late afternoon thunderstorms are from personal experience camping in the Purgatoire valley-whose beauty resembles a miniature Grand Canyon in places. They blow in from the West late in the day and may last for only a half-hour, but the winds and rain can be impressive. The second day of the dig, the winds accompanying the storm broke all three of the struts which gave shape to my tent. A more experienced archaeologist repaired them with the ever-present emergency kit - duct tape, and the tent survived the remaining three weeks of the dig-although in a some-what misshapen form.

The clay daubing in and on the dry-wall (no cement) stone walls of the stage buildings can still be seen. The sod roofs in the meller-drammer are from written records of stage journeys.

Stage Station Cuisine

Stage Station Cuisine

The Bent Canyon stage station was a “home” station, which means that meals would be served-though there is no evidence that turnips would be on the menu. The numerous spent .22 rounds found on the site, some fired by a gun whose firing-pin had been replaced by a nail-a repair taught to me by my uncles when the cost of a replacement was prohibitive, are evidence of the harvesting of the cotton-tail and jack-rabbits which abound in the area. One to five pounds of protein could be acquired at the cost of a 1/2¢ cartridge, thus increasing the profitability of the meals served. Most city dwellers would not recognize the meat in rabbit stew, hence the mystery meat.

Second only to the spent .22 cartridges in number found were casings for the .44-40 Winchester round. Introduced in 1873, the year that the U.S. army adopted the Colt Single Action Army (SAA) which used it, this was the most common large-bore cartridge of it’s day. This round could be fired in both the Winchester rifle and the Colt pistol. Firing-pin marks on the specimens recovered are from both pistol and rifle. This flexibility made it popular with cowboys and ranchers. The round was heavy enough to knock down for the table the numerous antelope which still inhabit the area and seemed to delight in playing “chicken” with the van which carried us from the campsite to the dig each morning.

One, possibly two, cartridge cases which had been fired by a Smith & Wesson “American” revolver were found at the site. This relatively rare pistol was used by the U.S. army from 1871 until it was replaced by the Colt SAA in 1873. It is interesting to speculate that the firing of these army revolvers might be related to the appearance of a mixed band of Apache, Kiowa, and Cheyenne marauders in the area of the stage station late in 1872.

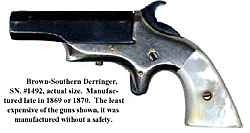

The most thought provoking find was a spent .41 short rimfire cartridge-the inspiration for the meller-drammer above. This round was introduced in 1863, as was the “National” derringer, below, which fired it. The cartridge was so under-powered that it would not penetrate the bark of a tree at fifteen paces, but it could be effective across a card table or the bed in a bordello.

Derringers were ineffective for hunting either animals or men and were relatively expensive-$4.75 compared to $6.50 for a Remington .44 revolver-the chances that a working cowboy, rancher, or farmer in this area would own such a luxury item are minimal. Ownership by a wealthy “city slicker” on the stage, who did not use a gun as a tool in daily living, is much more probable. This cartridge case doesn’t “fit” in the economy of the area for its era and may be the one artifact found which can be most securely related to the stage station.

To satisfy my curiosity, I purchased functioning antiques representing three of the most popular of the .41 short rimfire derringers, a few boxes of cartridges-highly valued by collectors of antique cartridges-and test-fired them. The only surprise was the amount of noise the explosions make. The psychological effect would have been paralyzing, even if the bullet were ineffective!

Derringers

Derringers

The derringer was not a practical tool for harvesting game. In addition to being under-powered, the little guns did not lend themselves to accuracy. An expert marksman fired five rounds from the “Southern” derringer, below, at a four inch plank at a range of three feet-without hitting the board!

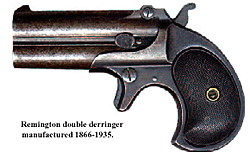

The most popular of these little guns was the Remington double-barreled model below. Over 150,000 of these were made between 1866 and 1935. This is the heaviest, most comfortable in the hand, most accurate, and most expensive ($8.00 in 1888) of the three. It also has a design flaw. Looking carefully at 4:00 o’clock beneath the screw on the top of the barrel, you can see a tiny crack, which widened to a complete break while extracting the 5th and 6th spent cartridges fired in it’s modern re-incarnation. A careful examination of others at antique shows revealed that almost all are cracked at this point where the metal is too thin for the metallurgy of the day-thus greatly increasing the price of those examples which are not cracked.

Firing the Remington derringer dispelled one of my fond memories from another era. We all remember the scene in the movies where the evil gambler in a dark-lit corner of the western saloon slung a derringer like this out of his sleeve and gunned down the drunken cowboy who objected to his dealing off the bottom of the deck. The evil gambler could probably have made a more secure living as a circus strong-man. Cocking this little gun preparatory to firing it requires the strength of both hands and isn’t easy!

So; which derringer fired the cartridge at the Bent Canyon stage station on that dark and stormy night? The only clue is the mark the firing-pins leave on the rim of the cartridge. Firing pins vary somewhat for the same model and change shape with age and use, but we’re exploring possibilities, not testifying as a forensic expert in court.

The mark of the pearl-handled “Southern” derringer (above right) most closely resembles the indentation on the archaeological specimen (above left). Definitely a ladies gun, hence the school-marm in the meller-drammer.

The Remington specimen had been the match, the derringer-firer would have been a Mississippi river-boat gambler fleeing vengeance.

Could the meller-drammer above have happened? Definitely! Did it happen? Probably not! There are things that we can know about history and things that we can only guess at, but understanding the forces that drive history is critical to mapping a safe path to the future. The human mind is designed to be interested in, and remember, the dramatic activities of our fellow man (gossip), not the dry facts of a telephone book. Telling history in a format that the human mind is eager to hear and remember makes the task of the student of history much easier.

Could the meller-drammer above have happened? Definitely! Did it happen? Probably not! There are things that we can know about history and things that we can only guess at, but understanding the forces that drive history is critical to mapping a safe path to the future. The human mind is designed to be interested in, and remember, the dramatic activities of our fellow man (gossip), not the dry facts of a telephone book. Telling history in a format that the human mind is eager to hear and remember makes the task of the student of history much easier.

If I had written that I spent four weeks digging, found two dozen shards of broken glass, eighteen iron nails, and definitely proved that the stone footing of a wall did not extend into a certain area, this account would be incredibly dull, but that is what happened on my adventure into field archaeology. The excitement is derived from imagining the possibilities.

Thirty years at a desk in an air-conditioned office 20 feet above sea level had not prepared me for scraping the clay from buried rocks on my hands and knees in 107 °F heat in the high desert of Southeast Colorado. Nor had the four-star hotels that international executives normally inhabit when away from home prepared me for porta-potties, an open-air shower heated by the sun, an aluminum cot in a tent pitched in a field of sagebrush and “cowboy corn”.

While the smell of a porta-potty remains nauseating, the “cowboy corn” was flavored with an exotic spice whose taste I hadn’t experienced in decades-hunger-and was delicious. The company was interesting and amazingly tolerant of an old codger, the view was breathtaking-I had forgotten that there were that many stars, the rabbits who came to my tent because the coyotes wouldn’t follow them there were cute, the attempts of my colleagues to identify tools that I had used as a young man on my grandfather’s farm were amusing, and adventure is where you find it. Most archaeological “digs” are horribly underfinanced and are willing to take on free labor, even retirees.

If you have an active mind, its more entertaining than re-runs of “I Love Lucy” - volunteer!

Back to Cry Havoc #37 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com