It was like leaning on a giant door that would not give--an isometric exercise which lasted for over 40 years. Such was the cold war. Pressing against the unyielding door on which the seemingly unmovable Russian bear was leaning from the other side produced over a generation of frustration--and stability. Now the door has flung open, and the United States and its allies find themselves falling through, landing with a thud, and looking up with a sheepish smile. As we get up and dust ourselves off, saying, "Darn right--about time," we find ourselves in unfamiliar surroundings.

It was like leaning on a giant door that would not give--an isometric exercise which lasted for over 40 years. Such was the cold war. Pressing against the unyielding door on which the seemingly unmovable Russian bear was leaning from the other side produced over a generation of frustration--and stability. Now the door has flung open, and the United States and its allies find themselves falling through, landing with a thud, and looking up with a sheepish smile. As we get up and dust ourselves off, saying, "Darn right--about time," we find ourselves in unfamiliar surroundings.

On the other side of the door we do not find an orderly society, rid of oppression and waiting for a little democratic touch-up paint, but something akin to Alice's Wonderland. Indeed, the situation is so dreamlike and confusing that it may call for a whole new way of thinking. Gone, at least for a while, is an enemy we could count on, as well as the world stability brought about by this superpower standoff.

Putting aside purely diplomatic considerations that will certainly provide endless entertainment for the US State Department, how does our military prepare itself for the coming era? How should we allocate and arm our forces? In order to produce a plan for the future, we must consider such questions, many of them seemingly unanswerable: Who is the enemy? What are his capabilities? Will the next war be limited or general? Is it even possible to conduct a general war without destroying the world? Is the expected enemy the one we will actually fight?

Anyone claiming to have precise answers to these questions is uninformed; experts--aware of the world's volatility--are the least certain of all. But Gen. Giulio Douhet, the maverick Italian air strategist, gone now for 60 years, had much to say about these matters. Although some of his specific recommendations were wrong, his general theories may provide a blueprint for the future.

The Strategy of Douhet

As early as 1921, General Douhet suggested that the solution to the next war--whenever and wherever it came--was not to conduct it like the last one but to use high technology to win it before the opponent can respond: "Victory smiles upon those who anticipate the changes in the character of war, not upon those who wait to adapt themselves after the changes occur." Contemporary military planners ignore these words--Douhet's greatest contribution to war-fighting strategy--at their own peril. Indeed, we should use--them as the basis for our plan for the 1990s and beyond.

Douhet was a product of World War I and witnessed all of the carnage that resulted when outdated tactics and strategy went up against high-technology weapons. Selected in 1912 to lead Italy's first aviation battalion, he saw firsthand how ineffective the land battle had become in total war between modern powers. He was convinced that high technology--machine guns poison gas, and aircraft--made warfare between large land armies obsolete. Further, he was certain that the technology of land warfare favored the defense.

For instance, if a World War I soldier in a defensive position (e.g., a trench) had a gun that fired one shot per minute and the attacker took one minute to cross the terrain to the entrenched soldier, Douhet reasoned that two attackers could overrun the position.

However, if the defender had a weapon that could shoot 100 rounds per minute, the enemy would have to send 100 victims and one victor to take the defended ground. And if the trench were protected by barbed wire that prolonged the trip across no-man's-land to five minutes, 500 bodies would litter the battlefield before the last attacker took out the defense. Thus was born the concept of the force multiplier in military planning, accompanied by the demise of the ground offensive (at least according to Douhet).

Douhet's calculations seemed precise to a fault, leaving no place for errant bullets or--as Paul Fussell points out in his book on the misery of war--"natural forces like wind and weather and psychological disruptions of purpose like boredom, terror, and self-destructiveness."

In other words, Clausewitz's "fog of war." Such na´vetÚ shows up again in Douhet's bombing plans; nevertheless, the foregoing illustration demonstrates the effect of technology on warfare. Moreover, his conclusion that defense had the upper hand was essentially correct; as many as 60,000 troops in a single battle were killed in ill-advised charges, and, as a result, World War I bogged down into what he called "crystallization of the lines," sending the conflict into a stalemate.

Thus, Douhet announced the end of the era when surrogate armies roamed Europe (or anywhere else) and fought wars for their countries. Technology had converted land wars into defensive struggles, which were destined to become stalemated, obviating any possibility of clear-cut victory. All future wars would be either total or general and would involve entire nations. That is, the dirty work could not be left solely to the soldiers (some of whom at times in history had been mercenaries)-civilians, too, would be involved in the next war. Most important, Douhet suggested that by giving the air force complete independence from the other services and by making the airplane the preeminent weapon system in the military arsenal, air power could become the instrument of victory in the next war.

Command of the Air

Douhet believed that, with the advent of technology, the army and navy had become "organs of indirect attrition of national resistance." The air arm, on the other hand, could act directly to break national resistance at the very source. But not just any air force would do. Douhet rejected the idea of an auxiliary air arm of the army or navy or a collection of "knights-errant" flying fighters.

Rather, he called for a fleet of massive, self-defending bombers that would dominate not only the enemy, but also the military budget of Italy--or any other country that would listen to his ideas. He wanted an air force that could win not just air battles but total command of the air. This command of the air would have a debilitating effect on the capability of land and sea forces, which would be relegated to a secondary role in future conflicts. The army and navy would remain part of an "indivisible whole" of the three armed services but would no longer be a significant factor in successfully resolving a war. With the ascendance of the air force, "the history of the war ... presents no more interest."

A Giant Bomber Fleet

In keeping with his vision, Douhet suggested that countries maintain modest armies and navies and devote most of their attention--and money--to air power, specifically bombers. Immediately after commencement of hostilities, these aircraft would be used against countervalue targets: population centers, transportation nodes, manufacturing sites, and important buildings, both public and private. The attendant devastation would cause the people (as opposed to the military) to lose the will to fight, and the war would end quickly.

The earlier the air attack the better, according to Douhet. He reasoned that waiting for an official declaration of war could be disastrous because the opponent himself might seize the opportunity for a first strike. He suggested using for the attack a combination of high-explosive, incendiary, and chemical weapons, with emphasis on the latter two. The explosives would be disruptive, the incendiaries would set fires and do the real damage, and the gas bombs (delivered last) would enhance the incendiaries' effectiveness by keeping fire fighters away, To be sure, this combination of weapons was quite nasty, and using them probably violated principles of gentlemanly fighting--but an early termination of hostilities would save lives. Douhet argued that since war is amoral--regardless of the methods--and inevitable, warring nations should get it over with as soon as possible.

He was convinced that the populace under attack would give up quickly: "The time would soon come when, to put an end to horror and suffering, the people themselves, driven by the instinct of self-preservation, would rise up and demand an end to the war."

No Defense

Douhet did not favor expenditures for any kind of defense against an air attack, remarking that "viewed in its true light, aerial warfare admits of no defense, only offense." Writing before the advent of radar, he maintained that such a defense was untenable since any given country has more countervalue targets than it can defend. Specifically, because no country could determine whether an attack were imminent, it would have to defend all possible targets. Even if detection of an attack were possible, the enemy's selected target would remain unknown.

Given this attitude (a little surprising in light of Douhet's vision in other areas of technology), his answer to defense was to knock out the opponent's air force before he has a chance to use it; this tactic was his only concession to counterforce targeting. (To Douhet, using planes against an opponent's army was useless. Aircraft might kill two-thirds of the enemy troops, but the other third might still be willing to fight. Furthermore, the effort would not stop the opponent's war-generation capability or, more important, affect the average citizen.)

Although some of his fleet of self-protected flying fortresses would be lost, he felt that most would reach their targets. After taking out the opposing air force, one's own air force would have air superiority and could then fly to any target unscathed.

Few Fighters

With regard to fighter aircraft, Douhet argued that--if they were used at all--fighters should protect the bombers. Certainly, they should not be employed in a futile defense of the homeland, and they would be completely wasted in engagements with other fighters because only a few enemy planes are destroyed, no land is captured, and the enemy's will is unaffected. All glory--no results.

Douhet was equally opposed to using what he called auxiliary air forces with the army and the navy. Aircraft employed by surface forces would be wasted since, to his way of thinking, the latter's efforts could never be decisive. A country would be better served by using its resources to build more bombers. He did, however, favor limited use of reconnaissance aircraft for target selection and escort for bombers. Like his computations for machine guns, Douhet used exact calculations to determine the effect of individual bombing attacks. He suggested that 10 aircraft carrying two tons of bombs each could destroy everything within a radius of 250 meters, which he called a "bombing unit." (Similarly, he used "fighter units" for protection of his bombers.) By determining the number of bombing units required to destroy a given target, he was able to size his force. Thus, Douhet attempted to make an exact science out of the very imprecise task of killing people.

The Efficacy of Douhet

At first glance, events since Douhet's time seem to disprove his theories about air power. Take, for example, the German blitz during the Battle of Britain. The Germans poured so many bombs on London, Coventry, and other targets in 1940 and 1941 that if any people had reason to lose their will to fight, the British certainly did. Instead, the bombing strengthened their resolve and made heroes out of the Royal Air Force fighter pilots who defended their country.

However, we must note that the Germans did not use chemical weapons on top of the incendiaries, as Douhet suggested. Had they done so, and if London or some other city had burned to the ground with no chance to rebuild--or if the land victory in Germany and the atomic bomb in Japan had not overshadowed the devastation of Hamburg, Dresden, and Tokyo (which conformed somewhat to Douhet's vision)--perhaps the outcome would have been different. To this extent, Douhet's theory did not get a full airing. But other examples from World War II show that air power did not win the war by itself.

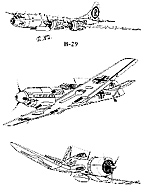

The B-17, B-24, and several other aircraft were exactly the types of platforms that Douhet had envisioned to win command of the air. They were relatively accurate, long-range bombers and were heavily fortified with turret machine guns for self-defense. Further, they were produced in large numbers in a short period of time. But both the Allies and the Axis produced equally large numbers of fighters and developed radar and accurate antiaircraft weapons. Therefore, bombers alone were unable to fly undetected and unopposed to targets deep within enemy territory.

The B-17, B-24, and several other aircraft were exactly the types of platforms that Douhet had envisioned to win command of the air. They were relatively accurate, long-range bombers and were heavily fortified with turret machine guns for self-defense. Further, they were produced in large numbers in a short period of time. But both the Allies and the Axis produced equally large numbers of fighters and developed radar and accurate antiaircraft weapons. Therefore, bombers alone were unable to fly undetected and unopposed to targets deep within enemy territory.

But the air war in World War II became so large, consumed so many resources, and was effective in so many places (fighter defense in the Battle of Britain, air-lift in Burma over "the Hump," naval air in the Marianas, and the bomber campaign against Germany, to name a very few) that Douhet's insistence on an independent air force was vindicated. Indeed, the air force is a separate military service in most nations today. Contrary to Douhet's sense of priorities, however, the US Air Force remains firmly committed to the support of ground forces in all of its missions, with the exception of strategic nuclear operations. The attitude of our military is that, with few exceptions, wars will still be terminated on the ground.

Some point out that Japan's quick surrender following the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki verifies Douhet's theory about undermining the national will. For example, in 1953 Bernard Brodie wrote that, because of the ability of atomic weapons to quickly destroy the fighting spirit of an entire nation, Douhet was probably more correct than ever (certainly, though, he should not be credited with anticipating nuclear weapons).17 Others argue, however, that the superpowers' ability to launch under attack and retaliate before being hit precludes the possibility of establishing command of the air (except against nonnuclear countries; even then, there is no assurance that a third party with nuclear weapons would not intervene).

So where do we go from here? We have seen that airplanes alone, although very effective, won't win the big war--unless it is nuclear. Nuclear powers have stalemated each other, making the prospect of a nuclear exchange--much less Douhet's general war--remote. What then? The answer lies in "anticipating the changes in the character of war."

Douhet for the 1990s

Today, there are two schools of thought on the sizing and generation of our military forces. The first, heard around the defense establishment, is that our erstwhile enemy, the Soviet Union, may have changed its intentions, but it can still destroy us. Therefore, we must plan accordingly. The second, a product of those people, who think that our economic problems over-shadow the military situation, is that we should relax because the Warsaw Pact has folded its collective tent and left town. On the one hand, these views may be complementary-perhaps we can draw down our military and still maintain a credible deterrent. On the other hand, either-or both-may be a prescription for suicide.

Nukes and Uncertainty

Since 1945, at least one fact has become clear: no one knows what is going to happen on the world scene tomorrow, much less next year or 10 years from now. We can also be reasonably assured that world peace is not forthcoming and that most countries will need some kind of military capability. Had they been polled 10 years ago, many people would have said that the world would eventually be destroyed by nuclear weapons. Today, however, those same people feel that these weapons, by virtue of their very existence, lessen the chance of general war and therefore are a stabilizing factor in international relations. Although there are no guarantees, this concept has held true since 1945, and our trigger finger hasn't even itched since the Cuban missile crisis in 1962.

Thus, continuation of nuclear modernization and deployment of weapons in sufficient numbers to maintain some sort of worldwide balance seems a prudent course of action and vital to our national policy. Although Douhet never mentioned the concept of deterrence per se, the principle is reminiscent of his own precepts, with a twist. That is, the advantage belongs to both sides--not just one. Beyond the nuclear foundation, we need to stop in our tracks and review every bit of past thinking to find the best answers to the questions posed earlier.

The number of possible scenarios in such a review precludes a comprehensive examination, but citing a few will demonstrate the difficulty of planning for them. First, Gorbachev could be deposed, either through the political process or a military coup, and a hard-liner could come to power. This action might reverse the clamor for independence that has swept Eastern Europe and has moved to the Soviet republics. Second, Eastern Europe, chafing under the rule of ill-chosen popular leaders, could find itself in civil war from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Third, Soviet republics could take the Lithuanian model to the extreme and elect open revolt. Thus, Gorbachev or his successor could find himself running, as George Will said, "the Duchy of Moscow" (but perhaps with a finger still on the nuclear trigger). Fourth, the two Germanys, moving inexorably toward reunification, could withdraw from NATO--shattering that organization--and become a real or perceived threat to the rest of Europe. Fifth, the non-Soviet Warsaw Pact countries could join NATO or some now alliance while the USSR festers in civil war. East, the US and USSR could become allies in a war in the Middle East or in one against nuclear-armed terrorist nations, or African nations engaged in border and food wars.

Which scenarios are likely? We just don't know. One man in power at the right place can make all of the difference--witness Stalin, Ceausescu, Noriega, Castro, and Hitler. Therefore, the US must use the most complicated of all force-structuring strategies: hedging.

Ways, Means, and Ends

Ways, Means, and Ends

By hedging, we mean the management of risk to our national interests. Any strategy is a balancing of desired outcomes (ends) against ways and means to accomplish those ends. Risk is the mismatch between any of the three elements. When military planners seek to minimize risk, they must address several matters: perceived threat, possible scenarios, available technology, direction of planning influence (top down or bottom up), mission, and money available.

Traditionally, the US has used the perceived threat as the basis for military planning. When possible threats outnumber any conceivable mix of forces, we use a "level of effort" approach--assigning available forces to perform at a certain level, regardless of the threat. Defense of the continental US is an example. All of the other factors weigh in at some point in the planning process, but the second most notable element (in addition to threat) is the monetary one.

We would like to have enough forces to meet the threat with minimum risk, but the available dollars usually do not allow that luxury. One does not need a Phi Beta Kappa key to realize that reductions to the defense budget are in the offing. The perception, accurate or not, is that the threat has gone south, so the military needs fewer bucks. With that as a given, available finances must not be used to sustain an artificial troop level that was never enough in the first place to match up with Warsaw Pact forces. That is, the fact that the US is morally opposed to using its troops as cannon fodder obviates any possibility that we can ever outnumber the forces of a country that is less scrupulous about its troops.

Consequently, we are left to hedge our bets and apply money where it will most likely have Some effect. Specifically, we can invest in superior technology and readiness for the next war. Our people must be happy, well equipped, flexible (ready to go anywhere since they relay may not be prepositioned), and prepared for the buildup when and if it occurs.

In the event of such a buildup, having the most modern systems on the production line would require only a surge, rather than a retooling, when time may be of the essence. In a drawdown like the one we are in now, Congress must fund the most advanced systems available (including sufficient modern airlift and sea lift). Saddling a reduced force structure with systems from the last war would be a fatal mistake. Not only must we modernize, but also we must reshape our thinking. That is how the United States should hedge. Douhet would be proud.

To the Future with Douhet

We have spent the past 40 years trying to envision what a war in central Europe would be like. Perhaps we should stop thinking of that location as the most likely place for the next war. Relatively speaking, we may be at the same point in modern warfare that Douhet found himself in World War I. That is, just as nineteenth-century weaponry was no match for the machine gun, perhaps twentieth-century combat aircraft are no longer any competition for modern-day defenses--at least in a maximum-threat environment. Like Douhet, we should redirect our attention and look for the next leaps in technology, some of which are already here: long-range standoff weapons, accurate tactical ballistic missiles (heretofore anathema to Air Force planners), drone aircraft, and stealth technology. We should, however, continue to include aircraft in plans that we draw up to counter sophisticated threats, regardless of the risk.

But we should realize that they will most likely be used to dominate a limited war. We should have no aversion to using B-2s (which would still be earmarked for our nuclear forces) in a conventional role against Libya or F-117s against Panama. Because we frequently have air superiority in a limited war and because such high-tech aircraft are highly survivable, the chances of losing them are remote. Furthermore, these aircraft could also survive the higher threat presented by a war in central Europe--at least until the next leap in defensive technology comes along. Employment of these platforms could very likely lead to an early cessation of hostilities and the saving of lives, much as Douhet envisioned.

Finally, we must continue to pursue technological improvements in the nuclear triad (intercontinental ballistic missiles, manned bombers, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles) since it is our insurance policy against major war. For the moment, our focus should be on the Trident D-5 missile, which will provide undetected hard-target kill. But as technology moves forward, it seems al-most a foregone conclusion that some day the oceans will become transparent to defenses, and we must plan for that contingency. We must not neglect the other two legs of the triad. We need to keep thinking, because technological advancements in one leg of the triad may make one of the others obsolete. For instance, perhaps a dyad of stealth bombers and submarine-launched missiles--or some other combination--is the ticket for tomorrow.

The world changes. The military that does not change with it or that is guilty of outmoded thinking can no longer be effective. Although Douhet's theories have not borne up in a number of critical areas, he was right on target with a statement that still speaks clearly to us: "Those nations who are caught unprepared for the coming war will find, when war breaks out, not only that it is too late for them to get ready for it, but that they cannot even get the drift of it."

Back to Cry Havoc #36 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com