At the age of six, my father passed down to me his single-shot .22 rifle. For the next twelve years that rifle provided a steady diet of rabbits in the fall and winter. Some of my uncles hunted rabbits, ducks, and squirrels with shotguns, but nobody had a pistol. The only game that you can hunt with a pistol is human – and strictly off the menu. Pistols just weren't practical for a poor farmer! But they are fascinating to boys of all ages.

The best-balanced and best-looking pistol ever made is the Colt 1860 Army. It's smooth lines made the boxy Colt Dragoon look clumsy. Firing a .44 inch round lead ball propelled by 40 grains of black gunpowder, the bullet has enough momentum to knock a man down. This was the weapon of choice on both sides of the Civil War. The Union bought about a million of them and the Confederacy made a copy (distinguishable by a brass frame). The best of the best is the Cavalry model. Its fluted cylinder reduces the weight and improves its appearance compared to the normal round cylinder. Colt is still manufacturing its line of black-powder pistols – with improved metallurgy!

The best-balanced and best-looking pistol ever made is the Colt 1860 Army. It's smooth lines made the boxy Colt Dragoon look clumsy. Firing a .44 inch round lead ball propelled by 40 grains of black gunpowder, the bullet has enough momentum to knock a man down. This was the weapon of choice on both sides of the Civil War. The Union bought about a million of them and the Confederacy made a copy (distinguishable by a brass frame). The best of the best is the Cavalry model. Its fluted cylinder reduces the weight and improves its appearance compared to the normal round cylinder. Colt is still manufacturing its line of black-powder pistols – with improved metallurgy!

But the weapon is not perfect. Sam Colt patented the wedge of metal between nipples on the cylinder of the revolver, which prevented the chain firing caused by an exploding percussion cap setting off a cap on the adjoining cylinders. But after loading the cylinder, the business end had to be filled with lard to prevent the blowback from a fired cylinder igniting the adjoining cylinders. (There is a gap between the end of the cylinder and the barrel of the gun. Fire from the exploding charge blows back from this gap into the cylinder on each side of the one being fired. These cylinders are not lined up with the barrel – detonation of the charge in them is a serious problem for the person holding the pistol – and anyone else in the vicinity. This is called chain firing and probably accounts for the lack of popularity of the Colt revolving rifle – which had a forestock in front of the cylinder.)

Another problem with the 1860 Colt Army is the sights. The pistol does not have a top strap (a piece of metal atop the cylinder). This makes it very easy to dis-and re-assemble but weakens the frame and leaves no place for a rear sight. The rear sight is a "V" cut into the top of the hammer. The gun is better for off-hand shooting than for carefully aimed fire. If you are holding the reins of a horse with one hand, ducking whatever is being fired or poked at you and trying to hit an enemy who isn't standing still, this is not a serious disadvantage.

However, if you are trying to win a black-powder pistol match and the competition are shooting match target pistols with double set triggers, you are at a distinct disadvantage. While I enjoy the camaraderie and the competition at the local muzzle-loading club's matches, I have conceived an ambition to win (or at least not come in last). After firing twenty-four rounds and hitting only one target, and that my neighbors, I decided that I needed some practice. So I load up all the necessary accouterments and head out to the (shooting) range. This includes the gun itself, gunpowder (FFF for pistols), No. 11 percussion caps, an in-line capper (a spring loaded device for installing the percussion caps on the nipples without breaking your thumbnails), a powder flask with attached measuring spout (made of brass with a spout cut to a length to measure the desired powder charge. A lever-operated cut-off valve lets powder pass when depressed and cuts off the flow when released.

Load and Shoot

To load, point the spout down, covered by the finger, depress the lever to let the spout fill and release the lever. The spout is filled with the correct charge – ready to be poured into the cylinder. Sam Colt was selling these to the government of Texas before Abe Lincoln had won a reputation as a lawyer), a bag of balls (The Colt .44 fires a .451 inch round ball, the extra .011 inches being shaved off when the ball is forced into the cylinder by the loading lever.

This gives a good seal to the cylinder, which is necessary to develop the pressure required to

propel the ball downrange.) – a flat-bottomed leather bag will sit there on the loading bench with its mouth open and pointed up and the balls readily accessible, and that all-important Colt tool, the combination screwdriver/nipple wrench.

This gives a good seal to the cylinder, which is necessary to develop the pressure required to

propel the ball downrange.) – a flat-bottomed leather bag will sit there on the loading bench with its mouth open and pointed up and the balls readily accessible, and that all-important Colt tool, the combination screwdriver/nipple wrench.

Last into the saddlebag is that modern contribution to the old west "wonder wads". These are 1/8" thick felt wads cut to .45 inch diameter circles and saturated with oil. Introduced within the last 35 years, they are set between the gunpowder and the lead ball and serve as an effective barrier to prevent chain firing from flashback and greatly improve the enjoyment of the hobby (fire ants will commit suicide in the tens of thousands to get at the combination of bear grease and lard formerly used to seal the cylinders). All of this is spread out on the shooting bench at the range.

After pinning up the targets (300 yard rifle targets at 25 yards for me), the gun is placed on half cock to permit the cylinder to rotate freely. With the barrel pointed up, powder is measured and loaded into each of the six chambers in the cylinder. A wonder wad is placed on each chamber and forced down squarely onto the powder by the loading lever. Then a lead ball is set on each chamber, the chamber is rotated beneath the loading lever, and the ball is seated securely on the wonder wad. Next the pistol is pointed down and a percussion cap is fitted onto each nipple. The gun is now ready to fire!

Firing six shots in rapid succession (it is a "six-shooter" after all!), I notice that the target has suffered minimal damage – this is going to take a lot of practice! And the deep boom and cloud of smoke from the gun have attracted the attention of everyone else at the range who gather around and want to know what I'm shooting. After they have all had a chance to fire the old gun I get back to some serious target practice – and notice that the cylinder of the pistol rotates only with great difficulty. After checking to make sure that a used percussion cap wasn't jamming the mechanism (the copper cups distort rather badly under the force of the explosion and tend to fall off of the nipples and into the internals of the pistol) I realize that the gun is so fouled with powder residue that it is dangerous to fire. Black powder, an intimate mixture of sulfur, charcoal, and saltpeter, leaves a lot of residue when burned. This residue is acidic and must be cleaned from the gun after each firing to prevent serious pitting. The residue build-up also coats the mechanism and makes mechanical operation difficult.

After extensive testing, I found that, if the gun had been well cleaned and oiled, I could fire thirty shots before the pistol had to be cleaned with hot water. Descriptions of Civil War cavalry engagements never mention breaking off action to ride back to camp, build a fire to boil water, and clean firearms. This leads me to the conclusion that less than thirty shots were usually fired from a pistol in any one engagement.

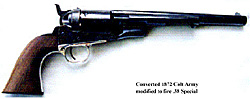

To get in more practice, I searched for a pistol with the same balance that fired fixed ammunition (cartridges you can buy commercially). My first attempt was a copy of the 1872 Colt Army modified to fire .38 Special – the most common (and cheapest) commercially available cartridges. This looks like the 1860 Colt from a distance, but has an ejector rod beside the barrel instead of a loading lever underneath it. Unfortunately, the

barrel is 1 inch shorter and much heavier – the balance is far forward of the balance of the 1860 Colt Army. My next attempt was a copy of the 1870 Richardson's (or factory) conversion. These guns were the result of an effort to extend the life of those @ million muzzle-loading

Colts bought by the federal government during the Civil War. A shorter, bored through cylinder was substituted for the original and a ring was fixed to the hammer plate which contained a floating firing pin and a loading gate (and a rear sight!). The loading lever was replaced with

an ejector rod. This gun has the same balance (and barrel length) as the 1860 Colt Army – and it can be fired several hundred times between cleanings!

To get in more practice, I searched for a pistol with the same balance that fired fixed ammunition (cartridges you can buy commercially). My first attempt was a copy of the 1872 Colt Army modified to fire .38 Special – the most common (and cheapest) commercially available cartridges. This looks like the 1860 Colt from a distance, but has an ejector rod beside the barrel instead of a loading lever underneath it. Unfortunately, the

barrel is 1 inch shorter and much heavier – the balance is far forward of the balance of the 1860 Colt Army. My next attempt was a copy of the 1870 Richardson's (or factory) conversion. These guns were the result of an effort to extend the life of those @ million muzzle-loading

Colts bought by the federal government during the Civil War. A shorter, bored through cylinder was substituted for the original and a ring was fixed to the hammer plate which contained a floating firing pin and a loading gate (and a rear sight!). The loading lever was replaced with

an ejector rod. This gun has the same balance (and barrel length) as the 1860 Colt Army – and it can be fired several hundred times between cleanings!

My aim was slowly improving until a retired policeman taught me the proper method for bracing the hands when firing a pistol – which enabled me to cut the bull's eye out of the target. Now I'm ready for the next muzzle-loading pistol match!

The retired policeman was shooting a stainless steel copy of the Remington New Army. Also a Civil War muzzle-loading revolver but a heavier gun with a top strap, a much stronger frame, sights that work, and a lower cost to Uncle Sam. This being true, why was the Colt so popular and only enthusiasts have heard of the Remington? The barrel and cylinder of the Colt can be removed by pushing out the cylinder wedge with your thumb, a loaded cylinder installed and the gun re-assembled and ready to fire in about ten seconds. This consideration may have overridden other features to insure its popularity. It would be interesting to compare the number of cylinders sold by Colt to the number of pistols.

The retired policeman was shooting a stainless steel copy of the Remington New Army. Also a Civil War muzzle-loading revolver but a heavier gun with a top strap, a much stronger frame, sights that work, and a lower cost to Uncle Sam. This being true, why was the Colt so popular and only enthusiasts have heard of the Remington? The barrel and cylinder of the Colt can be removed by pushing out the cylinder wedge with your thumb, a loaded cylinder installed and the gun re-assembled and ready to fire in about ten seconds. This consideration may have overridden other features to insure its popularity. It would be interesting to compare the number of cylinders sold by Colt to the number of pistols.

The friend (retired policeman) had made up his own ball lubricant – very important for muzzle-loading rifles. Unfortunately the lubricant worked too well in his Remington pistol – the balls rolled out of the barrel when the gun was fired. A lot of friction is required to build up the pressure required for propulsion; the ball lubricant removed the friction.

Test firing a revolutionary war era smoothbore flintlock – much like the smoothbore muskets used by the British, showed that after the fourth shot the barrel was so fouled that a fifth bullet couldn't be driven down the barrel with a hammer. To maintain volley fire with a smoothbore musket (remember – the quality of gunpowder in 1776 was much lower than today, the rate of fouling would have been worse!) the diameter of the ball must have been much smaller than the bore of the musket. This would account for the observation that if you were killed by a British musket at a range of over fifty yards; your death was an act of God. The grooves in a rifled barrel provide a place to force the fouling into – permitting more shots with a tighter fit between bullet and barrel – improving the muzzle velocity and accuracy. Finding a flint that sparks is a whole 'another story!

Test firing a revolutionary war era smoothbore flintlock – much like the smoothbore muskets used by the British, showed that after the fourth shot the barrel was so fouled that a fifth bullet couldn't be driven down the barrel with a hammer. To maintain volley fire with a smoothbore musket (remember – the quality of gunpowder in 1776 was much lower than today, the rate of fouling would have been worse!) the diameter of the ball must have been much smaller than the bore of the musket. This would account for the observation that if you were killed by a British musket at a range of over fifty yards; your death was an act of God. The grooves in a rifled barrel provide a place to force the fouling into – permitting more shots with a tighter fit between bullet and barrel – improving the muzzle velocity and accuracy. Finding a flint that sparks is a whole 'another story!

The 1860 muzzle-loading Colt Army does a lot more damage to the wooden pallets that the targets at the range are pinned to than does the .38 Special. In the 1870s and 1880s, many people noticed that the old Colts had more "stopping power" than the modern cartridge guns and kept them in use long after they were obsolete. First-hand experience with the quirks and foibles of the weapons used in previous wars gives one a deeper understanding of the events that we read about.

Back to Cry Havoc #32 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com