When the Union effort of the Civil War is spoken of most of what is covered is the great battle on land. Epics of great Union generals poetically overcoming the enemy are the scenes most often depicted. Some of these scenes include the names of Sherman and Grant and often attribute the land troops with winning the war.

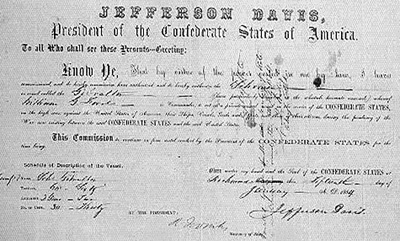

Letter of Marque issued by Jefferson Davis

Letter of Marque issued by Jefferson Davis

However, another branch of the Union military also played a crucial role in defeating the Confederacy the Union navy. It was this still underappreciated force and its blockade of Southern ports that really damaged the South's chances of winning the war.

The Blockade

As Union president, Abraham Lincoln had to regain order of his torn nation through tactics that went beyond the battlefield. His idea was to initiate a blockade around southern ports so that the South could not export or import any goods. Despite the lack of gallant battles it was devastating blow to the South.

War is an expensive endeavor. The South's main source of revenue was cotton. Without cotton and some other grains and cereals the Confederacy was squeezed for cash with which to buy the engines of war. When the first cannon fired on Fort Sumter, the South immediately lost the North as a consumer. The blockade was designed to cutoff its overseas trade.

Curiously the first economic blow to the South's need for money was itself. The South started the war by announcing an embargo on cotton. The embargo was an attempt at foreign policy arm-twisting. Britain was the main patron of cotton, importing 66% of its cotton from the South. Without the special goods the textile industry would collapse. France was also effected. Confederate President Jefferson Davis hoped "that the European powers who wanted It [cotton] would be forced by economic pressure to break the blockade."

However, after much deliberation the two countries decided that it was in their best interest not to get involved with the conflict in America. The South also found the in-flow of weapons severely restricted. Most gun manufacturing had taken place in the North. The Confederacy would now have to buy weapons elsewhere and at a high price.

Ever since the secession of the first state the South sought recognition of their country from outside and the Confederacy looked to Britain for recognition. Diplomats were sent to England from the South to help aid in the discussion. After much deliberation over the rules and conduct of the blockade the British government decided that the South was a belligerent power but not a nation recognizable under international law. It was a deft compromise. Other powers of Europe soon followed in Britain's footsteps. With the declaration came the knowledge that a belligerent force could buy weapons from neutral countries and had the power of "search and seizure." This gave the South justification to run the blockade for trading vital war supplies and cotton with foreign countries. And there were plenty of holes to slip through.

Necessity is the Mother of Invention

The blockade was a significant factor in the Union victory. Yet, in it's initial stages it was almost a disaster. If it were not for a few lucky factors on the North's side the blockade could have fallen into shambles. The navy, however, quickly demonstrated its capabilities and epitomized the phrase: "necessity is the mother of invention."

The blockade was a significant factor in the Union victory. Yet, in it's initial stages it was almost a disaster. If it were not for a few lucky factors on the North's side the blockade could have fallen into shambles. The navy, however, quickly demonstrated its capabilities and epitomized the phrase: "necessity is the mother of invention."

When Lincoln first announced the blockade in April 19, 1861, only three ships were available for service. The rest of the fleet was either not commissioned or sailing in distant waters. Also, the sailors available to man the ships were also very limited. Fortunately for the North the South had just shipped its season's cotton and initiated the cotton embargo mentioned earlier. This bought some time for Lincoln's "bluff" and allowed the navy to find other ways of utilizing existing supplies.

Ships were scarce so the navy turned to the commercial shipping to fill the immediate gap. Anything that could float and move by either wind or other sources of power was commandeered and commissioned a naval ship including ferryboats and antique sailing ships. Still the Union navy was only capturing one out of twelve traders coming from the South and it soon became obvious that the Union needed to build new ships.

The rapid construction of new gunboats became a critical factor. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles initiated the building of twenty "90-day gunboats" for immediate service. Welles, knowing the needs of the navy, did not wait for congressional approval. By June 1861, while only a handful of "90-day gunboats" had arrived for duty another question arose. Who would man the new ships?

The lack of qualified officers and sailors was serious. There was no time to put an inexperienced person through training. To fill the requirement the navy looked to its sister branch the Merchant Marine and to the commercial mariners for officers. Luckily for the navy many of the officers volunteered their services. As the navy soon found though, many of these eager volunteers lacked some of the skills needed to operate complex machinery. On one occasion a ship headed back to the wharf harbor it had just launched from because the engines were stuck in reverse.

In another instance:

- One ship went to sea with the Chief a regular ill: His four assistant engineers were a semi-literate fireman, promoted for his bravery in battle; a New Hampshire schoolmaster whose only acquaintance with engines was a picture in a textbook; his favorite pupil; and an ex-skipper of a tugboat.

The Blockade-Runners

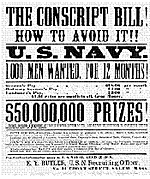

The single greatest threat to the success of the blockade was the blockade-runner. Davis initiated the commissioning of privateers since the Confederacy had no navy to challenge the Union's. Privateering made it legal for civilian craft to conduct military operations not only by running the blockade but also by attacking Union ships near ports. Still Confederate sailors suffered from the same lack of experience as their Union opponents, and the poor condition of their ships was appalling. Both led to the failure of privateering as a solution. However, blockade-runners became more inspired to conduct trading expeditions for profit not for just the South.

Profit & More Profit

The average cargo load was about 30,000 pounds. This cargo was worth many times more to the South since the "runners" were the Confederacy's only source of supplies.

The typical runner would load in the Bahamas and dash for southern ports during the night. Assuming the ship made it to a friendly port, they unloaded their cargo and went back for more. Money was not the only attraction.

Stevedores in Nassau unload cotton from a Confederate blockade-runner.

Stevedores in Nassau unload cotton from a Confederate blockade-runner.

In an issue of Harper's Weekly, a weekly magazine from the North, an anonymous runner speaks of the adventure and excitement of running the gauntlet. The man was a foreigner who lived in the South. The alien returned to his homeland to visit family and upon his attempt at arriving home he was arrested at the blockade line. Once he was released he decided to try his luck again. Crew on Northern ships patrolling the blockade became easily bored. In a little less than a month a sailor might only see one runner.

To keep the men's spirits high the Union enacted an incentive program. When a blockade-runner was captured its crew was sent to jail. Its cargo was also sent to land but not before the capturing crew got their share as dictated by the Government. This made blockade duty very popular and profitable. The captain would receive about 7 percent of the prize's value with a lesser portion for each officer, and 16 percent shared among the seamen. The other half was given to the government.

The Union Response

The blockade-runners forced the Union to take more vigorous action towards controlling the ports where the runners sortied. This meant that the ships would have to attack land targets, as well as, other ships. The capturing of strategic ports to aid in the maintenance of the blockade, make up most of the contribution of the navy to the Union effort. The blockade eventually stretched to over three thousand miles with only two bases in the South for Union ships to get supplies from. The Union decided to capture more points along the coast.

The first target was Hatteras Inlet on the North Carolina coast, nicknamed "the blockade-runners headquarters" due to the high volume of runner traffic passing through it. The Union officer placed in charge of the mission to deny it to Southern shipping has a passionate desire to do so. Silas Stringham had proven himself a major asset to the navy from the start of his career. He was rapidly promoted to Flag Officer (roughly equivalent to Commodore or Rear Admiral lower half) and given the command of the Atlantic blockading squadron. His plan for taking Hatteras Inlet involved the use of seven twenty gun ships and transports to land troops.

Stringham's plan defied the odds and normal naval practice no fleet had ever destroyed a fort without help from land forces and the idea seemed risky, even foolhardy. On August 26, 1861 Stringham landed his ground forces who were essentially ineffective. Stringham then ordered his ships into the fray and engaged the forts directly. After a day and a half of constant shelling the Confederate fortifications raised white flags in surrender.

Stringham's victory demonstrated the value of naval vessels in bringing considerable firepower to bear on a single point and the relative ease of movement compared to land based artillery of the same caliber. Unfortunately. Stringham, was the target of vitriolic criticism that overlooked his accomplishments and chastised him for not continuing the assault. In disgust he resigned his post as Flag Officer.

Port Royal

Flag Officer Samuel Du Pont took over from Stringham. Du Pont was an extremely brilliant officer with a "silver tongue." His men always held him in high regard and did all they were told. Du Pont continued capturing ports and reducing forts until he came to Port Royal. There he found himself confronted with what Confederate engineers thought was the strongest fort anyone could build.

On November 7, 1862, Du Pont moved against the harbor. His fleet consisted of three major ships, little more than gun platforms really, that bombarded the harbor with shell and shot while smaller ships covered the sides of the attack The South's weaponry was no match for the size and maneuverability of the Union arsenal. Troops landed to create a two pronged attack on the forts forcing the defenders to fight from two fronts. After a few hours the Union flag was hoisted over the harbor, the impregnable fortress a victim of its own reputation.

Denying the Ports

For Robert E. Lee, the success of the Union navy and its growing size were ominous portents and he "recognized that sea power gave the Yankees the option of striking when and where they pleased."

In addition to capturing harbors, the Union navy would sink old whaling ships in ports with shallow waters by sinking them in a narrow passage so that blockade-runners and other craft could not get through. Their extremely poor appearance earned the detachment the name, "The Rat Hole Squadron." The aging whalers would be filled with stones and then a hole cut in the ship's hull to sink it. The rocks helped stabilize the ship so it would not capsize while it sunk to the harbor floor. The technique was especially useful along the coast of North Carolina where there were many shallow inlets.

Ironclad

New ship design was the Confederacy's response to the Union threat. The most lasting was the steampowered ironclad the Virginia. Built at Norfolk from the abandoned Union ship the Merrimack, it was redesigned with steel cladding and logs creating a ship that laid low in the water. The new design was ideal for ramming other ships. and the Virginia sortied onto the James River to challenge the Union ships guarding its mouth and sunk two Union ships in a very short time.

Union naval engineers had been working on their own ironclad, the Monitor. The latest addition to the Union fleet, the steam driven vessel had a peculiar shape that was likened to a cheese box on a table. The steel hull cause the ship to float very deep in the water. Atop the hull was a revolving turret that enabled the ship to fire in any direction. The fabled clash of the Monitor and Merrimack lasted for several hours and was essentially a draw but it heralded in the age of iron ships.

As the war dragged on the blockade tightened. The Confederate war effort suffered as a result as ammunition and supplies were either captured or sent to the bottom. With an increasing inability to wage war from a lack of food, weapons, and other necessities, the Confederacy finally succumbed sin no small part due to the Union navy

Jason Ledbetter is a history major at Colorado State University. This is his first submission to Cry "Havoc!"

Back to Cry Havoc #27 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com