Author's Note: Most accounts of the Revolutionary War refer to the occurrence which I am about to discuss as the "Battle of Long Island." For our purposes, however, I am choosing to go with the name used by local historian John Gallagher, "The Battle of Brooklyn," since it was fought within the boundaries of this particular part of the island.

The port of New York was an important target for the British and their Hessian mercenaries during the early days of the Revolutionary War, one which they were certain could easily be captured with their vastly superior manpower and equipment. Once the port was secured, the British plan was to proceed north along the Hudson River to a point where they would hopefully rendezvous with forces moving south from Canada. This would effectively isolate the rebellious New England colonies from their southern neighbors.

A Geographical Background

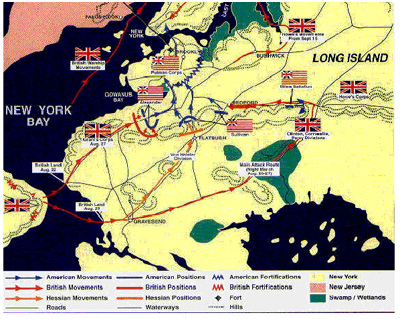

Located at the western end of Long Island, the six towns which later came to be known as Brooklyn consisted largely of farmland with a few small villages. As the Map illustrates, a long spine of hills, known as the Terminal Moraine, runs west to east through the area. Consisting of debris from the Wisconsin Glacier, these hills were largely covered with dense forest and underbrush, providing a natural barrier against invasion. The few roads that existed at the time roughly followed old Indian trails, and crossed the aforementioned spine though several narrow passes. Several of the major thoroughfares of the time, whose names are familiar to Twentieth Century New Yorkers, included Flatbush Road, a principal highway for farmers bringing their crops to port; Jamaica Road, which passed along the top of the Moraine, and Kings Highway, which intersected Jamaica Road at the pass with the same name. The village of Brooklyn proper was located in the area closest to Manhattan. Somewhat elevated in spots, it was partially isolated from the rest of Long Island by the Gowanas Creek on one side and Wallabout Bay on the other. A busy ferry service operated from the village to lower Manhattan.

Passing between south Brooklyn and Staten Island is the Narrows, a thin stretch of water which has always served as entrance to New York Harbor, and it was through this channel that the British intended to attack the port. Technically it would also have been possible to sail south along the New England coast and through Long Island Sound. However this roundabout course would have forced the entire fleet to pass through the Hell Gate, an aptly named strait full of strong currents, whirlpools and sharp rocks located where the Sound reached the East River. Many ships had been lost via this route, and it was therefore considered prudent to pass through the Narrows.

Washington's Strategy

The colonial forces in New York were most concerned about an invasion by sea. Being a collection of islands located on the East Coast, New York City would be difficult, if not impossible, to defend against an invasion by a well-equipped navy. The best that they could hope for would be to delay the invaders for a time.

Several months before John Jay had actually recommended that the city along with its surrounding farmland be burned, and that the Colonists instead build a base of operations further north along the Hudson. The highlands there, he believed, would be much easier to defend. Still, for political reasons, a serious attempt had to be made to defend the city. Washington has amassed about 19,000 troops in New York in the months before the fighting, but stationed only about 9,000 of these in Brooklyn, mostly in the area closest to Manhattan. General Nathaniel Greene was originally put in charge of these forces, but soon became ill, and was replaced by John Sullivan. A short while later the majority of Sullivan's command was given over to General Israel Putnam.

Although Washington and the men held him in high regard, Putnam was completely ignorant of the terrain under his supervision. As the map indicates, the colonists built a crescent-shaped series of forts and embankments running from Wallabout Bay (near the contemporary Navy Yard), across the area known then as Brooklyn Neck, to Gowanas Creek. It was behind this line of defense that most of the troops and weaponry were concentrated, and where Putnam spent most of his time. Several batteries were erected here, as well as in lower Manhattan and upon today's Governor's Island, to fight the enemy ships which

Washington feared would soon enter the harbor. Meanwhile, only token attention was paid to guarding the passes mentioned in the previous section, a decision which would later have serious consequences. Jamaica Pass, the most distant of these, had only a handful of guards, since it was not believed that the invaders would go that far east.

Most of Washington's men were poorly trained and equipped. Few had any real combat experience, and those who did often had not seen the large-scale, European style of fighting which would soon take place in Brooklyn. Their weaponry was anything but standardized, and some did not even have firearms. Those who did often brought their own hunting weapons, of different sizes and calibers, which made it difficult to maintain a suitable supply of ammunition. Although the hunting rifles that many carried were more accurate than their opponents' muskets, they were slower to load, and fired a much smaller projectile. Few of the men had bayonets, although many carried tomahawks. Uniforms were in scant supply.

In marked contrast to most of Washington's forces were a small group of highly trained and well-equipped Maryland and Delaware militiamen, whose bravery would later be celebrated. Even amongst these elite troops, however, enthusiasm for the Revolutionary cause was not as high as we would like to think. Indeed, many of the Marylanders had enlisted due to the scarcity of work in their home towns.

The British Arrive

On June 25, 1776, General Sir William Howe arrived in the Narrows with a flotilla of some 150 ships and 9,000 men. Rather than invade immediately, he and his men settled into Staten Island, which not only put up no resistance, but actually welcomed the arriving troops. Indeed, some 400 militiamen from the Island promptly switched allegiance to His Majesty's cause. Soon afterwards Howe was joined by his brother, Admiral Richard Howe, and later Admiral Sir Peter Parker arrived with still more men. In early August some 8,000 Hessian mercenaries completed the team, which had grown to a combined force of some 33,000 men and 320 ships. It was the largest trans-oceanic expedition which England had ever put together.

In contrast to Washington's newly-recruited band of ill-equipped fighters, the British forces, along with their Hessian mercenaries, were an effective group: experienced, disciplined and well-armed. Besides English and Hessians, their ranks also included Scots, plus a number of blacks from the Caribbean, who had been promised liberty from slavery once the rebellion was crushed. The typical British soldier at this time had ten years of experience, and carried a smooth-bore musket called a Brown Bess, which could also be equipped with a bayonet. The Brown Bess was not as accurate as a hunting rifle, but could be reloaded much more quickly, and fired a much larger slug. Besides, in the close, intense fighting which was to take place, accuracy was not that important to begin with.

Although contemporary Americans often think of these "Red Coats" as poorly-suited to the guerilla-type combat which they would face during the Revolution, the British also employed light infantry, who were well-versed in frontier fighting. Their ranks were supplemented by green-uniformed Hessian "Jaegers" (Hunters), who were also trained in flanking and skirmishing. Backing these troops was artillery in a wide range of sizes.

On two separate occasions Howe attempted to send a letter to "George Washington, Esquire," requesting a meeting in order to avoid a military confrontation. These were not accepted by the American troops whom Howe's messengers contacted, since they were not addressed to "General" Washington. A few days later a Colonel Patterson did succeed in meeting with the rebel leader. He was advised that he could not accept Howe's offer of a pardon, since the Colonists had done nothing wrong.

The Battle Begins

Howe's ultimate goal was to conquer the island of Manhattan. Rather than sail to this target directly, however, he decided to secure Brooklyn first. One reason was the resistance which his brother's ships would no doubt encounter from rebel artillery batteries at various sites around the island, as well as the sunken hulks and other maritime obstacles which had been placed in key channels in the harbor. Just as important, however, was the strategic value of Long Island as both a base of operations and a source of food for his men. Not only was the area covered with productive farmland, but its populace were for the most part still Tory, and could be counted upon to cooperate.

Beginning in the early hours of August 22 the first British forces crossed the Narrows in two groups. The first landed near present day Fort Hamilton, while the other came ashore further east.. Eventually three columns were formed: To the west, Col. Grant was to lead his men along the Shore Road along to the area near the Gowanas Creek. The middle column, consisting mostly of Hessians and Scots under the command of General DeHeister, were to proceed along the Flatbush Road. The most important section, however was to travel east under the direction of Generals Cornwallis and Clinton.

Beginning in the evening of August 26, the British right flank started along the Kings Highway towards Jamaica Pass. In the early hours of the next day, Grant's troops attacked Alexander's on the left front, and were repelled by the approximately 1,700 colonial troops there, who were under the command of Brig. General William Alexander, a.k.a. Lord Sterling. This engagement was a mere ploy on Grant's part to divert the Americans' attention away from the East, towards which the main body of British forces, some 19,000 men, proceeded. After reaching Jamaica Pass, which had only a handful of guards, they turned east, following a road which would roughly parallel today's Atlantic Avenue. At the same time, De Heister's Hessians and Scots moved down the Flatbush Road, towards the pass with the same name, behind which the Colonists waited with some 800 men and a few pieces of artillery. Howe was fortunate to have excellent intelligence, much of it coming from Loyalist sympathizers who lived in the area. Washington's forces did not have much information to work with, and had little idea what was to lie ahead. At 9:00 AM several shots rang out from cannon brought by the eastern British flank, which had by now reached the town of Bedford. This was the signal for the different forces to attack.

De Heister's men quickly over-ran the badly-outnumbered defenders of Flatbush Pass, who had only the time to discharge a single volley from their weapons before having to retreat in the face of an oncoming bayonet charge. Their long rifles were too slow to reload, and their greater accuracy was wasted in the thick brush surrounding the Pass. At the same time that De Heister's regular troops marched along the rutted road, his Jaegers were making their way along the sidelines, to further surprise the defenders. To their horror, the retreating Americans found themselves also under attack from British forces from the east, who had now reached the area to their rear.

In an area marked by several monuments in today's Prospect Park, the terrified new volunteers attempted to flee down the Fort Road, which intersected Flatbush immediately behind the pass, and led down to the waterfront, where they hoped to seek shelter behind the fortified lines. Those who attempted to surrender to the Hessians often found themselves bayoneted against trees, since de Heister's forces had been told that the rebels gave no quarter in fighting. One of the reasons why this was believed to be so was the fact that many of the Colonists carried tomahawks, as previously mentioned. Before the battle the British had spread rumors amongst the mercenaries that these primitive weapons were evidence of cannibalism on the enemy's part, making them completely untrustworthy. General Sullivan was captured, along with hundreds of his men who escaped the Hessian bayonets. We will discuss what became of them shortly. Many others simply fled into the woods and deserted.

While the land fighting was in progress, most of Admiral Howe's warships remained at anchor due to adverse wind conditions. He was able, however, to knock out a battery in Brooklyn Neck, and to unload some Royal Marines near Gowanas. It was in the swampy Gowanas area that the most celebrated members of the American forces continued to hold their ground, enabling those comrades who could to escape behind the fortified area nearby, which was still safe. The British had occupied a small stone house and placed several canon inside. Six times a group of some 400 Maryland militiamen under Lord Sterling charged the house, twice capturing it, only to be expelled again. Over 260 were known to have died, and all but about ten of the others were either captured or lost. Lord Sterling himself was taken prisoner. Writing later of his foe's bravery, Cornwallis remarked that "General Lord Sterling fought like a wolf."

Many of the fleeing colonial troops drowned in the marshes surrounding Gowanas Creek. By noon, those would could escape were safely in the fortified downtown area. Some of Howe's advisors argued for an assault upon these grounds, but he chose instead to wait. Opinions differ as to why he did so. Tired and hungry, his forces certainly needed a rest, and he no doubt recalled what had happened at Bunker Hill, when an attempt was made to charge an American fortification. While he and his men regained their strength, they began plans to break through the formidable barrier that the Colonists had built. Knowing that they would be easily overtaken when the fortress fell, Washington's men began preparing for a massive evacuation to Manhattan.

To deceive the British into believing that he would not immediately leave, Washington continued to bring some men to the Brooklyn encampment. Meanwhile, a heavy fog rolled in, accompanied by heavy rains and hail. Fortunately, some of the latest troops to arrive consisted of units from fishing villages in Massachusetts, who had years of experience rowing and handling small boats. Once darkness set in the Massachusetts brigade, using oars wrapped in cloth to muffle the sound of rowing, started ferrying men and equipment across the East River. Eventually every man and piece of machinery which could be moved was taken to Manhattan.

The Aftermath

Howe did not immediately follow the Americans into Manhattan. A short while later, he and the colonists met at a house on Staten Island in order to try and reach a peaceful settlement to the war. The negotiations were not successful. A short while later the British crossed the East River, and I will discuss the developments there in a future article.

Estimates of the casualties of the Battle of Brooklyn vary tremendously, especially when it comes to the number of Americans killed or wounded. There is simply no way of knowing what happened to many of the men who did not reach the colonial fortification in Brooklyn Heights. Some may have died in the woods; others drowned in the marshes, and no doubt others deserted. Gallagher, whose book gives the most thorough overview of the Battle which I have found, has confirmed at least 1,120 Americans killed, a figure that does not include several hundred estimated deaths. Howe claims to have taken 1,097 prisoners. The British army reported the loss of 61 men, with 257 wounded and 31 missing. This was in addition to about 20 Royal Marines. Five Hessians were lost, with another 23 injured.

Those colonial officers who were captured by the British were able to pass the time in occupied New York City fairly easily. Considered men of honor, they were allowed to move about town with relative freedom, and some even found themselves part of the local social circuit. The common soldiers who were taken prisoner were not as fortunate, for many found themselves confined to the hideous prison ships anchored in the lower East River. Years later Walt Whitman, who did a series on local history for a Brooklyn newspaper, described their fate:

- "These...unhappy men...were crowded together in the most infernal quarters, starved, diseased, helpless, any many becoming utterly desperate and insane. Death and starvation killed them off rapidly."

Visiting Battle of Brooklyn Sites Today

Anyone who lives in or visits New York City nowadays can easily see several key sites in the Battle of Brooklyn. There are monuments to the Marylanders in Prospect Park and Greenwood Cemetery, both close to where the actual battle took place. As a guide who has led walks through the area, however, I would recommend instead a tour which roughly follows the route taken by the fleeing defenders of Flatbush Pass, and leads to a replica of the stone house where the Marylanders fought. The best time to do this is on a weekend, when vehicular traffic is banned in the parks.

Battle Pass, as it is known today, lies within the confines of Prospect Park, along the Eastern Road, about a ten minute walk from the main entrance at Grand Army Plaza. Modern Flatbush Avenue lies several hundred feet to its north. Olmstead and Vaux, the Park's famous designers, wisely decided to let this key area remain largely as it was in 1776, so the contemporary visitor can see roughly the same landscape as did the troops. The Terminal Moraine is clearly visible here, and one can climb to its stop via a long series of stone stairs. Near the point where Washington's men had their artillery are two plaques commemorating the skirmish, while directly after going through the pass one will find a small monument which stands where an oak tree was cut down by Colonial forces to hinder the advance of the enemy.

After viewing the Pass, walk west through the park through the area in which the Hessians did some of their dirty work, down First Street, which roughly follows the route of the old Port Road. At Fifth Avenue, walk over to J. J. Byrne Park at Third Street, where a replica of the old Stone House (see at right) can be found. Many of the slain Marylanders are reportedly buried nearby, although there are no markers to commemorate this. If one continues down to Third Avenue, the Gowanas Canal flows through the area into which many of the escaping colonists fled.

After viewing the Pass, walk west through the park through the area in which the Hessians did some of their dirty work, down First Street, which roughly follows the route of the old Port Road. At Fifth Avenue, walk over to J. J. Byrne Park at Third Street, where a replica of the old Stone House (see at right) can be found. Many of the slain Marylanders are reportedly buried nearby, although there are no markers to commemorate this. If one continues down to Third Avenue, the Gowanas Canal flows through the area into which many of the escaping colonists fled.

In future articles I will be covering what happened when the British did invade Manhattan, as well as the situation in occupied New York. I would be glad to correspond with anyone interested in this or any other aspect of New York City history.

Please feel free to send e-mail to historic-ny@mindspring.com.

Notes on the Illustrations: The map used below is part of a larger one that appeared in the Soto article. All photographs are Copyright 1998 by Tony Rohling.

Bibliography

Christman, Henry M. (Editor), Walt Whitman's New York, New York, New Amsterdam Books, 1963, pp 31-42.

Gallagher, John J., The Battle of Brooklyn, 1776, New York, Sarpedon, 1995

Homberger, Eric, The Historical Atlas of New York City, New York, Henry Holt, 1994, pp 14-49.

Kammen, Michael, Colonial New York, Milwood, NY, KTO Press, 1975, pp 337-375.

Soto, Jose, "Battlefield: New York," Military Technical Journal, April, 1997, pp 22-26.

Stokesbury, James L., A Short History of the American Revolution, New York, William Morrow, 1991.

Back to Cry Havoc #25 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com