New technologies inevitably foster new ways of war, and the way nations organize their armies to fight. The advent of nuclear weapons (or atomic weapons as they were then known) after 1945 forced military professionals to think seriously about how they would affect strategy and tactics. The US Army's concept of the nuclear battlefield during the Eisenhower era (1953-61) led to a short-lived and radical reorganization of the US Army's ground divisions on the Pentomic concept where, as the name implies, divisions were organized on the Rule of Fives (penta) in order to fight and survive in a nuclear environment (atomic).

Mushrooms on the Battlefield

The Korean War was mainly fought using World War Two equipment, with American firepower pitted against Communist manpower and infiltration tactics, but two things made Korea different. Besides the political dimensions of the conflict, which often imposed bizarre limitations on military actions, Korea was also the first conflict in which the possibility existed of atomic weapons being used on the battlefield. During the conflict, the US Army debated at length how atomic weapons, especially the newer tactical types ( tactical is generally defined as any nuclear warhead with a nominal yield of less than 15 kilotons), would affect the battlefield of the future.

Research and development continued on smaller and more efficient warheads and new delivery systems. One of the new weapons, while it was never actually used, helped to end the Korean War. In May 1953, the United States field tested the atomic cannon, a 280mm gun which could fire a ground-penetrating atomic shell of 15 kilotons yield up to 17 miles. A veiled threat to use this weapon in Korea was made to the Chinese and this undoubtedly was a factor in their decision to sign an armistice in July of that year.

The Eisenhower years were a difficult time for the Army. The Army continued trying to develop new weapons and tactical systems in an environment composed of disagreement with Eisenhower s policies of massive retaliation and the New Look for the armed forces (which combined to concentrate spending on strategic nuclear weapons and the Air Force, at the expense of the Army and Navy s budgets), the knowledge that the USSR, which had exploded its first bomb in 1949, was developing its own arsenal of atomic devices, and a naive belief that sophisticated weapons and massive firepower could substitute for human presence and ability on the battlefield.

During the 1950's, the Army spent as much as 40% of its available funding for R & D in any given year on guided missile and tactical atomic weapon development. The intention was to provide a range of atomic-capable artillery at all command levels, to be used on offense or defense. The 280mm atomic cannon was soon discarded as insufficiently mobile and short-ranged, and work continued on developing atomic shells for the existing 108 and 155mm guns.

In 1953, the Corporal liquid-fueled guided missile was fielded, followed in 1956 by the longer-range Redstone. These weapons were intended to be corps or army commanders atomic-capable assets. In 1954 the Honest John, a truck- mounted unguided rocket with an atomic warhead and a range of 22 miles, was fielded as a division commander s nuclear asset. This was followed in 1956 by Little John, a trailer-mounted airportable rocket launcher with a range of 10 miles, intended for airborne divisions and light units.

The smallest such delivery system was not issued until 1961and was to provide regiment and battalion commanders with manpacked nuclear artillery. It was called Davy Crockett, and consisted of a 150-pound rocket that could loft a tiny atomic warhead up to 2000 yards.

Pentomic Concepts and Organization

As the new weapon systems became available and were incorporated into the Army s arsenal, there was much debate on the proper tactics to use on the nuclear battlefield. Did atomic weapons represent merely an increase in available firepower (albeit a quantum leap), or did they demand an entirely new way of fighting? How should ground units be configured so as to make best use of the abilities (and, on defense, the limitations) of atomic weapons?

The Army's senior leadership, consisting of General Matthew Ridgway (Army Chief of Staff, 1953-55), General Maxwell Taylor (Army Chief of Staff, 1955-59), and General James Gavin (Deputy Chief of Staff for R&D) — these three generals were known as the Airborne Club because they had all commanded airborne divisions during World War Two — thought a drastic reorganization was needed.

The new divisions should exhibit the following three characteristics:

Flexibility, or dual capability

This referred to the ability to operate equally efficiently on nuclear and non-nuclear battlefields. The size of the Army declined dramatically during the Eisenhower years, and its leaders realized that whatever troops were available in the standing army could be sent anywhere in the world at any time to deal with anything from a localized insurgency to an all-out atomic war.

Mobility

The Army realized, from the harsh lesson dealt it in the first three months of the Korean War, that it was necessary to have the strategic mobility to reinforce American or allied units anywhere in the world within days, if not hours, of hostilities. This translated into units being air-portable, if not actually paradrop-capable. Once arriving at the battlefield, units would have to be tactically mobile as well.

Depth

Similar to the modern AirLand Battle doctrine, there would be no more well-defined front lines with relatively safe rear areas. Instead there would be an area of battle, a deep and fluid zone in which units would have to stay widely dispersed in order not to offer a concentrated target for atomic weapons. Breaking the division into a larger number of independent components would allow this dispersion.

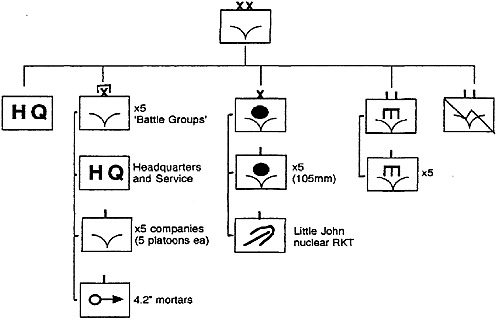

The Army developed a new structure for infantry and airborne divisions designed to fulfill these three requirements, based on five Battle Groups instead of three regiments as its main components (hence the name Pentomic).

The armored divisions kept their old establishment of eight maneuver battalions (four tank, four armored infantry) that could be organized into two or three combat commands as needed. Because airborne units were the lightest and most adaptable to the new pattern, or possibly because of the influence of the Airborne Club, the 101st Airborne Division was the first Army unit to convert, in the fall of 1956.

Infantry divisions remained somewhat heavier than airborne units, but in general total manpower was reduced by about 20-25%, while the number of front-line troops rose (125 combat platoons versus about 90 in the old-pattern division) as did the number of helicopters and manpacked crew served weapons.

Pentomic Tactics

With this reorganization came a new set of tactics, in line with the concept of fighting the non-linear battle. On the offense, the emphasis would be on blasting a hole through the enemy with as many tactical atomic weapons as required, relying on their shock and disruptive value as well as their destructiveness. The atomic bombardment would be followed by a rapid penetration and exploitation by mechanized battle groups moving in column.

"Ignored were [the] effects on the local civilian population and infrastructure, the permanent devastation and poisoning of the countryside, and the effect on friendly troops."

"Ignored were [the] effects on the local civilian population and infrastructure, the permanent devastation and poisoning of the countryside, and the effect on friendly troops."

On the defense, the general plan was to entangle the enemy in a mesh of well-spaced islands of resistance, then cut his supply lines by moving in mobile Battle Groups from the flanks or using more tactical atomic weapons. These islands were to be at once too small in size to make a target for an atomic warhead, but large enough to deal a decisive counterblow; too widely dispersed for any strike to take out more than one island at a time, but close enough to be mutually supporting. Not surprisingly, no clear guidelines for their size or interval were ever set.

On paper, these tactics seemed to work well. Even Eisenhower supported the idea of the Pentomic divisions, although apparently only because it meant even greater reductions in the size of the Army. However, the concept failed at several key points:

It demanded too much of subunit commanders.

A division commander had no intermediate level of command, and could in the case of a widely-dispersed division find himself and his staff trying to coordinate the actions of up to sixteen different units! A Battle Group was more than a battalion but less than a regiment, and could count on less conventional fire support than under the old configuration. This lack of firepower would be addressed in 1959 when the divisional artillery was reorganized as five composite artillery battalions (of one 105mm and one 155mm howitzer battery each) and would have been further remedied in later years by issuing Davy Crockett launchers at Battle Group level.

This had drawbacks as well: two types of guns in the same battalion posed difficulties in training, supply, and flexibility, and having Davy Crocketts on hand implied placing atomic weapons, albeit small ones, in the hands of jumpy young majors and captains once the Battle Group began to suffer officer casualties.

It did not take into account the collateral effects of atomic weapons

Ignored were their effects on the local civilian population and infrastructure, the permanent devastation and poisoning of the countryside, and the effect on friendly troops. Neither, in practice, was the need for planning and coordinating atomic strikes more carefully than conventional artillery bombardments seriously addressed. Army planners, while refusing to accept the plausibility or morality of the Eisenhower doctrine of massive retaliation, also seemed to believe that tactical nuclear weapons could be tossed about freely on the battlefield without inviting escalation to larger weapons.

The logistical base was too thin.

Wider dispersion and the larger number of subunits at each level increased the demands on the supply echelon. Meanwhile, the Pentomic reorganization had drastically reduced the amount of logistic support available in order to raise front-line strength. During exercises and tests, it was found that the amount of support available was inadequate to deal with the requirements of even a non-nuclear attack or defense, and that riflemen had to be combed out from forward units to keep the supply system working.

Strategic mobility (i.e. air-portability) did not translate into tactical mobility.

During the Eisenhower years, most American infantry units remained non-mechanized. Trucks could not traverse terrain devastated by atomic weapons, nor did they give their passengers any protection against fallout or enemy strikes. The M113, the first true mechanized infantry vehicle, did not fully enter service until 1960 — its development had been a casualty of the Army spending so much R&D money on atomic weapons. In 1959 some infantry divisions received a transport battalion of M113s, enough to carry one Battle Group at a time, and a small group of H-34 transport helicopters. However, tactics to use these new machines had not been fully worked out.

Pentomic Failure

The Pentomic experiment, never very popular, lasted less than five years. While the new organization was designed to give Army units the mobility they needed to be a global police force, the structure to make best use of tactical atomic weapons, and the dual capability to function on nuclear and non-nuclear battlefields, in the end it proved unable to accomplish any of these goals.

Within one year of Kennedy assuming power in 1961, the Pentomic concept had been replaced by the ROAD (Reorganization Objectives Army Division) program, which relied on a division base structure on which a varying number of battalions suited to the mission could be hung. Meanwhile, the new doctrine of counterinsurgency had claimed the spotlight in military professional journals, moving the focus away from nuclear weapons and setting the stage for the commitment of a reconstituted Army in Vietnam.

Organization Chart

Back to Cry Havoc #21 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com