In December 1186 Reynald des Chatillon, the Lord of Kerak and a vassal of the King of Jerusalem, Guy de Lusignan, violated the King's sworn truce with Saladin and attacked a Muslim caravan en route from Damascus to Cairo. The booty was enormous and among the hostages was Saladin's sister. Saladin's request for the return of the caravan was followed by a royal entreaty to Reynald. The Lord of Kerak rebuffed both his king and the Sultan, declaring that "he was master on his land as the king was on his." The raid and Reynald's arrogant reply set into motion a chain of events that led to the critical battle of the Crusader era.

In December 1186 Reynald des Chatillon, the Lord of Kerak and a vassal of the King of Jerusalem, Guy de Lusignan, violated the King's sworn truce with Saladin and attacked a Muslim caravan en route from Damascus to Cairo. The booty was enormous and among the hostages was Saladin's sister. Saladin's request for the return of the caravan was followed by a royal entreaty to Reynald. The Lord of Kerak rebuffed both his king and the Sultan, declaring that "he was master on his land as the king was on his." The raid and Reynald's arrogant reply set into motion a chain of events that led to the critical battle of the Crusader era.

Convinced the Franks could no longer be trusted, Saladin resolved to be done with them once and for all. From Damascus he called for jihad. Mobilizing the armies of Damascus, Aleppo, Egypt and northern Syria he assembled the largest Muslim force ever to prepare for war. When they marched on the fortress of Tiberias in June 1187, the sight of the army, according to the Arab chronicler al-Imad, "made men think of the Last Judgment."

At Acre, the Crusaders, under the nominal command of Guy de Lusignan, had been rapidly building their own force. Months of political wrangling and intrigue had complicated the issue. Raymond III, the Prince of Antioch, considered Guy a usurper of the throne he felt was his by right. After Reynald's raid Raymond had quickly concluded another truce with Saladin. In March the Sultan requested permission to send 7000 men across Galilee into the Kingdom of Jerusalem on a twelve hour "demonstration."

Raymond agreed provided no harm was done to the land or the people. The Muslim troops were true to their word but on the return journey were challenged by a few hundred Knights Templar under their Grand Master, Gerard De Ridefort. The Muslims, attacked under a guarantee of safe passage, slaughtered those whose did not escape and left Christian territory with the heads of Templars on their lances.

Despite the fact that it was the Templars who had violated the guarantee, Raymond could not ignore the outcome. He went to Acre and was reconciled with the king. But Raymond's presence divided the court. A popular figure, a natural leader and a skilled general Raymond should have been given command of the army by Guy, who was unpopular, a foreigner and militarily inept (facts he recognized in himself). But Raymond's earlier alliance with Saladin allowed his two bitterest personal opponents, Gerard De Ridefort (who had escaped the slaughter of the Templars by fleeing the battlefield) and Reynald des Chatillon, to intrigue against him. For his part Raymond knew that both men had conspired to deprive him of the throne.

The Christian army at Acre was the largest since the First Crusade. While different sources give various numbers, there were approximately 3500 armored knights of which 300 were Templars or Hospitallers. (An additional 900 knights were supplied by Gerard De Ridefort out of money given to the Knights Templar by Henry II in expiation for the murder of Thomas a' Becket). This heavy cavalry was supported by some 30,000 Christian infantry and 4,000 tucopoles (Muslim mercenaries).

Garrisons Depleted

To raise this force Guy had milked dry the garrisons and fortified cities of the Kingdom. Jerusalem, for example, was only defended by three knights. The Frankish army had extremely high morale. The reconciliation between Guy and Raymond, despite the back room intrigues, meant the greatest unity in the history of the Latin domains. The Christians also knew that if they could defeat Saladin's army it would mean years of relative peace. Finally, inspiring them with religious fervor, was the presence of True Cross. God would not desert them.

On the other side of the frontier Saladin waited patiently for the Franks to assemble. The army he commanded was about twice the size that of the Christians. In addition to his numerical superiority he had confidence in his considerable gifts as a general.

The morale of his troops was also high. They had declared jihad and had the blessings of Allah and the prayers of all Islam on their side. Saladin also knew that the garrisons and cities were empty of defenders and that victory over the Christian army meant he would be master of Syria within a few days of its defeat. Saladin wanted battle, but also feared it.

Eighty years of Franco-Muslim war had shown that numerical superiority was a feeble weapon against the Franks. He had twice as much cavalry but it was light cavalry against armor.

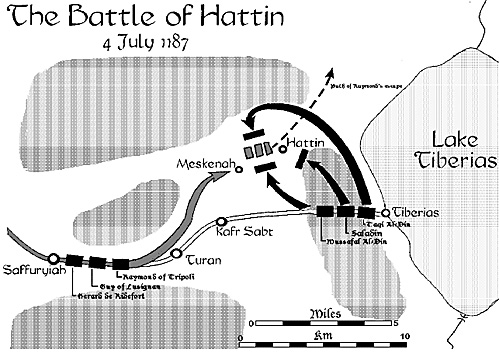

On July 2, 1187 Saladin made the first move, crossing the Jordan River and laying siege to Tiberias. The town, located on the shores of the lake of the same name (also known as the Sea of Galilee) fell quickly. His men the surrounded the castle and the nearby fields disappeared beneath their tents. Holding out in the citadel was the garrison and Raymond's wife, Eschiva, and his children.

On July 2, 1187 Saladin made the first move, crossing the Jordan River and laying siege to Tiberias. The town, located on the shores of the lake of the same name (also known as the Sea of Galilee) fell quickly. His men the surrounded the castle and the nearby fields disappeared beneath their tents. Holding out in the citadel was the garrison and Raymond's wife, Eschiva, and his children.

Saladin's position was tactically dangerous. Lake Tiberias was at his back and if defeated he had nowhere to retreat. On the other hand the nearest water was at Sephoria. To reach him the Crusaders would have to march twenty miles across the desert in the searing summer heat.

At Acre a message from Raymond's wife described the desperate state the fortress was in. Raymond advised Guy against marching to their rescue. To go forward, he argued, was to allow the Saracens to choose the place of battle. Gerard and Reynald went to Guy and used the Prince's reluctance as evidence of his treason. The common soldiers for their part clamored for the opportunity to do what chivalry demanded — the rescue of women in distress.

The army reached Sephoria (Kitron) and halted. There was water from several wells and springs and the early July heat was well over 100 F. Raymond again argued for the army to stop. "Let Saladin waste himself on Tiberias while we remain on the defensive and await an opportunity to counterattack him." The main concern should not be Raymond's family or the castle he told Guy. He could ransom his wife and children. Tiberias could be retaken later. The preservation of the army was all that was important. To march forward was folly. There was no water between Sephoria and Tiberias except one small spring, he pointed out. To advance was an invitation to annihilation. Guy agreed and the army was ordered to assume defensive positions.

At midnight Guy was secretly visited by Gerard de Ridefort. The Grand Master accused Raymond of cowardice, treachery and of being allied with Saladin in a conspiracy to seize Guy's throne. Guy, a weak willed individual who owed his throne to Gerard caved in.

Dawn

When dawn broke the army was ordered to advance. Saladin received the news with a sigh of deep satisfaction. "That is what we wanted." Saladin then sent several light cavalry units to pin down the Christian army and slow its advance. They met the vanguard, commanded by Raymond, engaged it then swarmed around it to assault the main body. By noon the water was gone and the exhausted men began to straggle. The march was now a race to water — the Crusaders had to reach the shores of Tiberias or the Jordan by night fall. Standing between them and their next drink was Saladin's army. Delay would be fatal. Raymond went back to Guy and persuaded the king that the army had to press forward as quickly as possible.

Then a message came from Gerard. The Templars, manning the rearguard, were under heavy attack by Muslim bowmen. To Raymond's astonishment, Guy turned the army around and marched to the rescue of the Templars. The delay meant that the army could not hope to reach the water it needed.

As night fell the thirsty, exhausted Christians were still five miles away from Tiberias. The army assumed a defensive posture on the 1,191 foot high hill of Hattin. A bare, rocky place with no water, tradition held that this was the Mount of the Beatitudes, where 1200 years earlier Jesus of Nazareth had proclaimed "blessed are the peacemakers."

The hot, tired and thirsty men got little sleep. Saladin moved the largest portion of his army to surround the hill. Relays of horse archers sent showers of arrows into the encampment throughout the night. When dawn broke, Saladin ordered forward seventy camels laden with arrows to resupply his horse archers. With the wind at his back and blowing directly into the Crusader camp, Saladin then set fire to the dry grass of the plain. Half dead with thirst, exhausted by the rising heat, the Franks found themselves suddenly enveloped in smoke and flames. Behind the choking walls of fire was Saladin's host barring the way to water.

Half of the infantry surrendered within an hour. Atop the hill the armored knights assembled, then charged the Muslim lines with unbounded ferocity, intent on reaching the lake. So savage was the attack that Saladin actually thought, for a moment, that he had been defeated. When the charge was blunted Raymond III wheeled and broke through the western arc of the Muslim encirclement, escaping to Sephoria with a portion of the army. Chroniclers ascribed his motives to cowardice, treachery or an act calculated to allow his troops and some of the chief leaders to escape.

Atop the hill the remaining Christians fought in the shadow of the True Cross which was held aloft over them. When a Muslim force captured it the effect was electric. Al-Imad, a witness to the event, wrote "when the Christians knew that the Cross had been taken from them, none desired to escape."

For a Muslim to notice this the Crusaders must have responded in a spectacular way — in the midst of a hell of thirst, blood and defeat there was a brief resurgence of the Crusader spirit on the hill. But it was too late.

The defeat at Hattin was complete. The carnage was terrible. All around the Mount of the Beatitudes was a gigantic charnel house of men and horses. Despite the large number of dead there were more prisoners than killed and wounded. Among them were the King of Jerusalem, Guy de Lusignan; his brothers; the Lord of Kerak, Reynald de Chatillon; the former Count of Edessa, William of Montferrat; and Gerard de Ridefort.

Reynald des Chatillon, whose unwise raid on a caravan had started the war was beheaded by Saladin who said to the terrified Guy — "a king does not kill another king but this man's perfidy knew no bounds." All of the Hospitallers and Templars, except Gerard de Ridefort, were executed. The rest were spared, and along with the True Cross, fifteen thousand Christian warriors were taken, in chains, to Damascus.

Hattin was the turning point in the struggle between Christian and Muslim, Crusader and Turk, for control of the Holy Land. The battle critically weakened the military position of the Franks and completely demoralized the Christians. The loss of the True Cross was taken as a sign that God had abandoned them. In the immediate aftermath, city after city fell on Saladin's approach. Impregnable fortresses yielded in a day when his banners appeared before them. The Kingdom of Jerusalem was expunged. It was the beginning of the end. Nine more Crusades failed to undo what had been done that July 4th.

Map

Back to Cry Havoc #21 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com