The new Sultan of Egypt, Qutuz, beheld the four men before him with a mixture of hatred and justifiable anxiety. They were the envoys of Hulegu Khan, the great Mongol prince who had punched through Persia and into Fertile Crescent, leaving blood and destruction in his wake.

The new Sultan of Egypt, Qutuz, beheld the four men before him with a mixture of hatred and justifiable anxiety. They were the envoys of Hulegu Khan, the great Mongol prince who had punched through Persia and into Fertile Crescent, leaving blood and destruction in his wake.

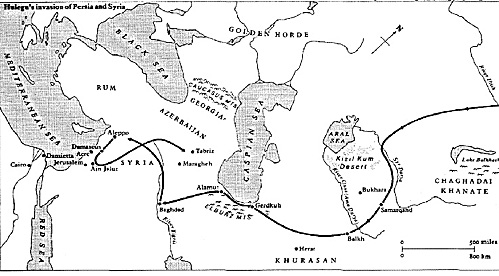

Two years earlier, in 1258, Hulegu had marched on Baghdad and ravaged the city with a ferocity beyond comprehension. His men savagely destroyed 500 years worth of carefully collected learning and culture, destroying libraries, museums and technological enterprises. Capturing the last Abassid caliph, Hulegu had treated his prisoner to a dinner, then ordered the caliph sewn into a Mongol carpet and crushed to death under the hooves of his cavalry's horses. Marching into Greater Syria he had spent a few short weeks destroying the power of the Assassins, reducing their mountain fortresses to rubble. Hulegu had gone on to sack Aleppo and entered Damascus on March 1, 1260. Now his attention was focused on Egypt.

The envoys carried a letter from Hulegu to Qutuz. It was not written in the tones one head of state normally addressed another:

- From the King of Kings of the East and West, the Great Khan. To Qutuz the Mamluk, who fled to escape our swords.

You should think of what happened to other countries ... and submit to us. You have heard how we have conquered a vast empire and have purified the earth of the disorders that tainted it. We have conquered vast areas, massacring all the people. You cannot escape from the terror of our armies.

Where can you flee? What road will you use to escape us? Our horses are swift, our arrows sharp, our swords like thunderbolts, our hearts as hard as the mountains, our soldiers as numerous as the sand. Fortresses will not detain us, nor arms stop us. Your prayers to God will not avail against us. We are not moved by tears nor touched by lamentations. Only those who beg our protection will be safe.

Hasten your reply before the fire of war is kindled ... Resist and you will suffer the most terrible catastrophes. We will shatter your mosques and reveal the weakness of your God and then we will kill your children and old men together. At present you are the only enemy against whom we have to march.

Qutuz, was indeed a Mamluk. The Mamluks had originally been a group of purchased slaves who then had been converted to Islam, becoming, over time, Egypt's military leaders. Qutuz, the one time commanding general of Egypt's armies, had come to the throne only a few weeks earlier by knowing how and when to act. Observing the dissolute and vapid character of the Ayubbid Sultan, he deposed him, stating "Egypt needs a warrior as its king."

Qutuz, was indeed a Mamluk. The Mamluks had originally been a group of purchased slaves who then had been converted to Islam, becoming, over time, Egypt's military leaders. Qutuz, the one time commanding general of Egypt's armies, had come to the throne only a few weeks earlier by knowing how and when to act. Observing the dissolute and vapid character of the Ayubbid Sultan, he deposed him, stating "Egypt needs a warrior as its king."

A proud, decisive man he not used to being addressed in terms of a coldly arrogant challenge and ultimatum. He pondered the message for a few moments and reached a decision. The Mongols, he knew, considered ambassadors to be untouchable. They treated those sent to them with utmost respect and expected theirs to be treated the same. To harm one, they considered a declaration of war without quarter.

Qutuz coldly ordered the four ambassadors seized. On his orders they were cut in half at the waist and their heads placed on the great Zuwila Gate of Cairo. It was not a lightly made decision. Ever since the days of Ghengis Khan the Mongols had been invincible. From a small region north of China they had pushed westward across the steppes into Russia and Poland, through Persia and into Mesopotamia and the Levant.

At the same time they pushed south into China. In the process they had developed cavalry tactics and the operational art to a hitherto unknown level. Military historians are fond of pointing out that the Mongol armies of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries still hold the record for the fastest sustained rate of advance. They rolled over all opposition, destroying anyone who tried to resist. Now Qutuz had bloodily announced his intention to resist. The die was cast. Egypt and its Mamluk rulers were irrevocably committed to war with the Mongols.

The Mongol Response

Hulegu commanded an army of some 100,000 Mongol cavalry and began to push from Syria preparing to march into Palestine and sweep into Egypt. The Mamluk armies took steps to defend Egypt against the expected assault. Then a messenger brought word to Hulegu Khan, that the Great Khan, Monge, had died. In keeping with Mongol tradition all the princes, including Hutlegu, were summoned to Mongolia to attend a Kuriltai (Council) to elect his successor. Ironically the death of the previous Khan had caused the westernmost armies to pull back after conquering the Poles. Hulegu pulled his main army back to Maragheh, leaving his chief general and advisor, Kitbuqa, in Syria with an army comprised of two tumens or about 20 000 Mongols. Kitbuqa was ordered to press on to Egypt.

Kitbuqa first sent a raiding party into Palestine, cutting the usual Mongol path of pillage and slaughter through Nablus all the way to Gaza, but he stopped short of Jerusalem, then held by the Crusaders.

The Crusaders were essentially too weak to provide any significant resistance against the Mongols but Kitbuqa hoped a show of charity might convince the Franks to ally themselves with the Mongols. An unlikely alliance had already been achieved when the Christian King of Armenia and the Prince of Antioch joined Hulegu in his triumphal entry into Damascus. To the eastern Christians, the Mongols were engaged in nothing less than a new Crusade to free the Holy Land of the Muslims. Kitbuqa, himself a Christian, expected that his co-religionists to ally themselves with the Mongols against a common enemy. He completely misunderstood them.

The Crusaders leaders responded with raids on the new Mongol-held territories and the two sides came to blows at Sidon. The Mongols besieged the city and on entering it plundered the town and massacred its citizens. Only the Castle of the Sea and its garrison held out.

In Egypt, Qutuz ordered a halt to the construction of defenses and commanded his men to advance against the Mongols. With the major part of the Mongol army in Persia and the open conflict between the Crusaders and Mongols at Sidon, it seemed the opportune moment to strike. At the same time he sent envoys to the Crusader leaders in Acre asking for safe passage and the right to purchase supplies.

To the surprised Franks the request presented a thorny question. To cooperate with Qutuz would mark the Crusaders as enemies of the Mongols, opening all their territory to the wrath of the Hordes — the full strength of which they knew they could not resist. On the other hand, Qutuz was the only hope of ridding the region of the foreign invaders. After a lengthy debate the Egyptian request was agreed to.

Qutuz Advances

On July 26, 1260, the Egyptian army began to march. The vanguard was under the command of Baibars, an aggressive, competent commander who swept away the Mongol force in Gaza without waiting for the main body. The war had begun. Kitbuqa, from his base at Baalbek in modern Lebanon, assembled his army and began a march to the south, moving down the eastern side of Lake Tiberias (Sea of Galilee).

Qutuz led his army north eventually camping on the outskirts of Acre. There while the nervous Crusader leaders watched his army pitch their tents in the shadow of the city, he planned his next move and purchased supplies. Word soon arrived that the Mongols, and a large contingent of native Syrian conscripts, had circled Lake Tiberias and were approaching the Jordan River, following the same invasion route used by Saladin in 1183. Qutuz ordered the army southeast to meet them.

On September 3rd, Kitbuqa turned west across the Jordan and up the rising slope to the Plain of Esdraelon. Qutuz established positions at Ain Jalut, the Springs of Goliath (the place local tradition held that David had slew Goliath). There vast the plain narrowed to just under five kilometers wide, protected on the south by the steep slope of Mount Gilboa and by the hills of Galilee on the north. Qutuz placed units of Mamluk cavalry in the surrounding hills, while ordering Baibars and the vanguard forward.

Both sides approached the coming battle with a desperate sense that there was no alternative to victory. To everyone Muslim it was obvious that Islamic power stood at the precipice. One more significant Mongol victory and Islam, as a political power, was finished.

There was more. Ghengis Khan's policy of remorseless brutality and no mercy might have been effective in paralyzing lesser men, it had stiffened the resolve of the Mamluks and reinforced their determination. Before the advance, Qutuz, in a speech that brought tears to the eyes of his men, reminded them of the nature of Tatar savagery. There was no alternative to fighting, he said, "except a horrible death for themselves, their wives and their children." It steeled the souls of the Mamluks for the coming battle against an enemy they knew had never tasted defeat.

The Springs of Goliath

Baibars advanced quickly and made contact with Kitbuqa's force coming towards Ain Jalut. Seeing Baibars' force, Kitbuqa mistook it for the entire Mamluk army and ordered his men to charge, leading the attack himself. The two armies collided and both seemed to stop in the fierce clash that followed.

The Springs Of Goliath

The Springs Of Goliath

Then Baibars ordered a retreat. The Mongols rode triumphantly in pursuit, victory in their grasp.

When they reached the springs, Baibars ordered his army to wheel and face the enemy. Only then did the Mongols realize they had been tricked by one of their own favorite tactics: the feigned retreat. As Baibars re-engaged the Mongols, Qutuz ordered the reserve cavalry out from its hiding places in the foothills and slopes and against the Mongol flanks. Realizing that he was now committed to a battle with the entire Mamluk army, Kitbuqa ordered his ranks to charge the Muslim left flank. The Mamluks held, wavered, held again but eventually were turned, cracking under the ferocity of the Mongol assault.

As the Mamluk wing threatened to dissolve and it appeared the entire army might be routed, Qutuz rode to the site of the fiercest fighting and threw his helmet to the ground so the entire army could recognize his face. "O Muslims" he shouted three times in stentorian tones. His shaken troops rallied and the flank held. As the line solidified, Qutuz led a countercharge sweeping back the Mongol squadrons.

Kitbuqa was now faced with a deteriorating situation. When one subordinate suggested a withdrawal his response was brief: "We must die here and that is the end of it. Long life and happiness to the Khan."

Kitbuqa was now faced with a deteriorating situation. When one subordinate suggested a withdrawal his response was brief: "We must die here and that is the end of it. Long life and happiness to the Khan."

Despite the relentless Mamluk pressure, Kitbuqa continued to rally his men. Then his horse took an arrow and he was thrown to the ground. Captured by nearby Mamluk soldiers he was taken to the Sultan amidst the sounds of battle. "After overthrowing so many dynasties you are caught at last I see," Qutuz exulted.

Kitbuqa, for his part, was still defiant — "If you kill me now, when Hulegu Khan hears of my death, all the country from Azerbijan to Egypt will be trampled beneath the hoofs of Mongol horses." In a move calculated to insult his captor, Kitbuqa added "All my life I have been a slave of the khan. I am not, like you, a murderer of my master" Qutuz ordered Kitbuqa executed and his head sent to Cairo as proof of the Muslim victory.

With their leader gone, the remaining Mongols fled 12 kilometers to the town of Beisan where they drew up to face the pursuing Mamluk cavalry. The resulting clash broke the remnants of the Mongol force and the few that could escaped crossed the Euphrates. Within days the victorious Qutuz re-entered Damascus in triumph, and the Egyptians moved on to liberate Aleppo and the other major cities of Syria.

Epilogue

What happened in the valley of Ayn Jalut was one of the most significant battles in world history, yet it is a rare Western history class that even hears mention of it. This is ironic because the battle was as important for Western civilization as those fought at Marathon, Salamis, Lepanto, Chalons and Tours. Had the Mongols succeeded in conquering Egypt, they would have been able to storm across North Africa to the Straits of Gilbraltar. Europe would have been clamped in an iron ring all the way from Poland to the Mediterannean. The Mongols would have been able to invade from so many points that it is unlikely that any European army could have been positioned to hold them back.

More immediately, the battle and its outcome, smashed the myth of Mongol invincibility. Qutuz's superior generalship had shown the vaunted Mongols were just as fallible as any army. The psychological impact worked both ways.

The Mongols were shaken. Their belief in themselves never quite the same. Ain Jalut also marked the end of any concerted campaign by the Mongols in the Levant. Except for a few small contingents sent into Syria to conduct revenge raids, the Mongols never attempted a reconquest of the lands that Sultan Qutuz had wrested from them.

For Qutuz, the ecstasy of victory was relatively short lived. After Aleppo was retaken, Baibars suggested that he be given the emirate of the region as recognition of his contributions. Qutuz refused.

When the Mamluk army was only a few days from its triumphal return to Cairo, Baibars went to see Qutuz on a matter of state. Reaching out in greeting he grabbed the Sultan's sword hand and withdrew a dagger from his belt driving it into Qutuz' heart. When the army entered Cairo, Baibars rode at their head as Sultan — destined to be the greatest of all Mamluk warriors. But that is another story.

Map: Hulegu's Invasion of Syria and Persia

Back to Cry Havoc #19 Table of Contents

Back to Cry Havoc List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by David W. Tschanz.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com