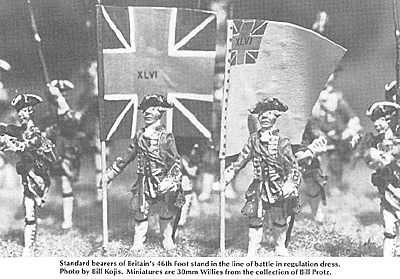

Standard bearers of Britain's 46th Foot stand in the line of battle in regulation dress. Miniatures are 30mm Willies from the collection of Bill Protz. Photo by Bill Kojis.

Standard bearers of Britain's 46th Foot stand in the line of battle in regulation dress. Miniatures are 30mm Willies from the collection of Bill Protz. Photo by Bill Kojis.

Theme Editor's Preface:

I have taken the liberty of presenting articles regarding British uniforms of the era written separately by Bill and Wayne to present one allied effort to maximise information. The first piece written by Bill concerns British uniforms in general while the second composed by Wayne highlights one regiment, the 60th Royal Americans. - Bill Protz

The British Armyon parade in the mid-Eighteenth Century must have been a glorious sight. Imagine - the pomp and ceremony of drill being conducted by officers and NCOs in scarlet coats decorated lavishly with lace and wearing clean white gaiters. Picture the grenadiers wearing heavily embroidered mitre caps. The Highlanders, pipes a-droning, marching in scarlet coats and wearing belted plaids. Yes, it must have made an incredible sight.

Then shots were exchanged in 1754 between French regulars and Col. Washington's Virginia provincials at a place called Great meadows in far off America-and yet again the British Army was required to prepare for battle against their old enemies, the French. This time the battles were to be fought in that trackless wilderness -- America. The fight in North America, through rugged terrain and against an enemy that was at first primarily composed of Indians, Canadian militia, and "Colony regulars" (Compagnie Franches de la Marine), caught the British Army unprepared.

By the middle of the 18th Century the uniforms of the British Army had been regulated to the point that, outside of the facing colors, most of the regiments looked the same. British infantry wore collarless "scarlet" coats that hung to just above the knees. Wide lapels, rather wide, slashed cuffs, and the linings of the coats, these kits of which were worn turned back, were all in the facing color. The lapels, button holes, and cuffs were decorated with distinctive regimental lace. The coat was further decorated with lace panels above the slash in the cuffs and lace around the pockets. When the weather was cold or inclement, the lapels of the coat could be worn closed.

Under the coat was worn a red, long-sleeved waistcoat that hung to midthigh. The edges of the waistcoat and pockets were normally trimmed with lace. Breeches were red for all regiments except those that were designated as "Royal" regiments. Royal regiments wore blue breeches.

White gaiters (brown during campaigns) were worn to mid-thigh, covering stockings and the knee and lower thigh of the breeches. The men wore black shoes and black felt tricorns. Tricorns were edged white. The cockade was black. Grenadiers wore heavily embroidered 12" tall mitre caps, the fronts of which were generally in the facing color. The lower portion of the rear of the cap was also in the facing color and the upper rear portion was red and trimmed with lace.

A wide, light buff leather belt was worn over the left shoulder and supported a black ammunition pouch worn at the right hip. Another belt of the same color was worn over the waistcoat around the waist and held a bayonet and sword. When the coat was closed, this second belt was worn on the outside of the coat. Hair was worn about shoulder length and tied back with a black ribbon. Beards and mustaches were forbidden.

This then was the regulation uniform worn by the British infantry in 1754. However, conditions in North American dictated changes and changes were indeed made. At the end of the War of Spanish Succession, in 1713, England received Acadia from France and renamed the area Nova Scotia. The 40th, 45th, and 47th Foot were stationed in the new town of Halifax in the early 1750s. These regiments were dressed in the regulation manner. After the disaster at Great Meadows, the Colonial Governors clamored for the dispatch of British regulars to the colonies to discourage French encroachment on lands that the Governors felt belonged to the English Crown. Consequently, in early 1755, General Braddock was sent to Virginia with the 44th and 48th Foot - both understrength. Braddock ordered changes in the uniforms and the manner of equipment transportation and thus began the evolution of the British uniforms to meet the conditions found in North America.

Braddock's men were marching over mountains and through forest, cutting a road as they went. He ordered that waistcoats, crossbelts, swords and other bulky equipment be left in the wagons. Waistcoats and breeches were of a lighter material, probably a white linen, than the customary wool.

Brown canvas gaiters replaced white. Knapsacks were worn over the right shoulder and pads were to be worn under the tricorn to prevent sunstroke. Sergeants and officers still wore their sashes and both carried firearms.

Also raised in 1755 for the campaign in New York were the 50th Foot (Shirley's) and the 51st Foot (Pepperell's). Both regiments were raised in North America and ended the campaign in the garrison of Oswego where they were decimated by illness. Both regiments were apparently uniformed in standard issue uniforms that had silver buttons. After the fall of Oswego to the French in 1756, both units were disbanded and numbered units following #51 were reduced by two numbers.

During 1756 the 22nd Foot, the 35th Foot, and the 1st battalion of the 42nd Highland Regiment arrived in North America. Of these, the 42nd is noteworthy because they wore traditional Highland garb. The 42nd wore a short scarlet jacket without lapels. The collars and cuffs were in the buff facing color. The waistcoat was red and the lace was white with a red stripe. The most distinctive part of the uniform was the belted plaid kilt in what was known as the "government tartan" pattern. This pattern was a checked design of light greens and bluish grays that was lighter in color than the modern version that we think of today.

The 42nd wore the belted plaid only for ceremonial purposes and generally wore the "Feilidh beag" or short kilt in the field. Headgear consisted of a dark blue bonnet with a small red porn on the top and a black bearskin tuft on the left side. Grenadiers wore black bearskin mitres with a small red front plate. The hose was red and white checked. Red and white checked shirts were preferred because they did not show dirt as easily as white ones.

The entire unit, including officers and NCOs, carried broadswords and the light infantry muskets. The light company was issued tomahawks. Each soldier furnished his own sporran which was often made from otter and many of the men equipped themselves with dirks, which were about the length of a forearm.

King George II declared the 42nd a "Royal" regiment on July 3,1758 - five days before the battle at Ticonderoga. The unit was notified to change their facings to blue sometime later.

During 1757 Brigadier Lord Howe and an additional ten regiments arrived in North America. Lord Howe spent some considerable time on missions with Roger's Rangers and learned to appreciate the style of fighting done by this outfit. Consequently, he turned his own regiment, the 55th, into virtually a light infantry regiment. The following quotes are from the Elting volume and are in turn taken from letters and notebooks of the period: "He [Lord Howe] forbade all displays of gold and scarlet and set at the example of wearing himself an ammunition issue coat... one of the surplus soldier's coats cut short... he ordered the muskets to be shortened and the barrels of theirguns were all blackened... he set the example of wearing leggins... Lord Howe's [hair] was fine and very abundant, he, however, cropped it and ordered everyone else to do the same." "We are now literally an army of Round Heads*. Our hair is about an inch long; the Flaps of our Hats, which are wore slouched, about two inches and a half broad. Our coats are docked rather shorter than the Highlanders... The Highlanders have put on Breeches and Lord Howe's Filabegs... Swords and Sashes are degraded, and many have taken up hatchets and wear Tomahawks."

The reference to Round Heads dates back to the mid 17th Century during The English Civil wars, 1642-48. The Royalists called their opponents Round Heads because of the short hairstyles worn by the Puritan faction in the Army of Parliament. - Bill Protz

"Every effort apparently was made to fit the men for woods fighting... 10 Rifled Barrelled Guns were delivered to each regiment to be put into the hands of their best Marksmen. Whenever the men march they carry their provisions in the haversacks and roll them up in their blankets like the Rangers."

Thus the 55th came to appear as a light infantry battalion. Extra pockets were sewn onto the waistcoat to hold additional ammunition. Hat brims were cut down and worn "slouched". Sometimes the front peak was left and worn to resemble what we now would call a baseball hat or that peak might be turned back against the front of the hat.

The remainder of the troops that accompanied Howe and Abercromby on the Ticonderoga expedition - the 60th, 27th, 44th, 88th light infantry, and the 42nd Highlanders, appear to have followed these regulations to a greater or lesser degree and might appear somewhere in between the regulation uniforms and those adjustments ordered by Lord Howe.

The 78th (Fraser's) Highland regimentarrived in North America late in 1757 and spent the winter training with the Rangers. The 78th looked much the same as the 42nd, only with white facings. They wore the "government tartan", black belts, and had silver buttons. On campaign the wore little decoration or lace and, surprisingly, they probably did not adopt the short kilt. It appears that they were issued the shorter light infantry musket.

The value of light infantry troops became so apparent that by the middle of the war light companies were formed in each regiment. These companies were usually converged together and functioned as separate units of about 500 men. The coat was discarded and the sleeves were sewn onto the waistcoat. The waistcoat had extra pockets for ammunition. Leather leggings replaced the gaiters and the men were issued a hatchet and tomahawk rather than a sword. Some of these troops adopted Ranger dress. At the end of the war all regiments were ordered to add light companies.

The value of light infantry troops became so apparent that by the middle of the war light companies were formed in each regiment. These companies were usually converged together and functioned as separate units of about 500 men. The coat was discarded and the sleeves were sewn onto the waistcoat. The waistcoat had extra pockets for ammunition. Leather leggings replaced the gaiters and the men were issued a hatchet and tomahawk rather than a sword. Some of these troops adopted Ranger dress. At the end of the war all regiments were ordered to add light companies.

On Wargaming the Period

Tired of all of this historical stuff? Want to know what it means to a French & Indian War armchair general? As a wargamer all that has preceeded was essentially background. Want to paint your British units bright red and paint all of the lace? - fine, your troops just disembarked in New York and are undergoing a review. Want to paint them all in buckskins with green and brown leggings?-fine, it's 1760 and your troops have been in the field for several years.

Let's consider the French & Indian War for a moment. The troops were outfitted in England in regulation uniforms that were designed forfighting in Europe. They were issued one coat, one waistcoat, one pair of breeches, and a couple of shirts. They traveled on a long sea voyage to North America and then spent, perhaps, several months awaiting the new campaign season. They may then have been marched several hundred miles through forests, hogs, rain, etc., in a land that had few or no roads. Possibly the most respected General in the war had issued orders that regulations must be radically changed. How did these troops appear?

The red dyes of the period as well as the quality of the cloth used for uniforming privates of the British Army were neither very good. Consequently, the red of the coats, waistcoats, and breeches, could appear as anywhere from dark red and almost orange. Officers and NCOs should be painted as more or less scarlet. Rangers, light infantry companies, and regiments that spent considerable time in the field might very well have had beards. By the end of the war the first battalion of the 60th reportedly dressed much as the Rangers - in green. The lack of resupply and the harshness of the terrain caused many adjustments to the uniforms.

Much of what you can or may want to do depends on what castings you are using. If you want to make your troops appear uniform, you will want to make each unit from one casting. If you wish to make your units historical and to simulate much of the skirmish warfare by basing your figures one to a stand, you may want to get figures from several different companies and paint them irregularly. Obviously, you can convert figures to give your troops different looks. Let's face it, outside of Quehec, there weren't many European style lines of battle drawn during this phase of the war. Skirmishes, sieges, and ambushes were the major actions in North America.

The French & Indian War makes for very enjoyable gaming. You don't have to paint up a zillion guys to represent your army and the addition of those inconstant allies, the Indians, can make for some fun afternoons. You can justifiably represent the color and pageantry of the 18th Century armies and, at the same time, put out Indians, Coureurs, regulars, milia on both sides, and provincial units - all dressed differently. You have the various shades of red for the British regulars, the blues, browns and greens of the provincial units, the greens and black of the Rangers, the grayish-whites of the French regulars, the various garbs of the frontiersmen on both sides, and the variety of Indian clothing- all on the same table. This setup can have considerable eye appeal and, if you are playing with a set of rules you like, the French & Indian War can be one of the most enjoyable periods in which to game.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barthrop, Michael. British Infantry Uniforrns Since 1660. Poole, Dorset, England New Orchard Editions 1982

Bootstin, Daniel J., ed. The Chicago History of American Civilization. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1964. The Colonial Wars 7689-1762, by Howard W. Peckham.

Chartrand, Rene and Summers, Jack L. Military Uniforms in Canada 1665-1970. Ottowa National Museums of Canada. 1981.

Elting, John R., general editor. Military Uniforms in America The Era of the American Revolution 1735-1795. San Rafael, CA: Presidio Press. 1974.

Funcken, Fred and Funcken, Lilliane The Lace Wars, vol. 1. London: Ward Lock Limited. 1977.

Kennedy, Ludovic, general editor, The British at War London: Hart-Davis-MacGibbon, 1973 vol. I: The Seven Years War, by Rupert Furneaux.

Parkman, Francis. Montcalm and Wolfe. Now York: Atheneum. 1984.

Scollins, Richard. "Redcoats in North America". Military Modelling (July, 1979: pp. 595-6, 616.

Tindall, George Brown. America, A Narrative History 2 vols. New York. W.W. Norton & Co., 1984.

Windrow, Martin and Embleton, Gerry, The Military Dress of North America 1665-1970 London Ian Allen Ltd. 1973

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1989 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles covering military history and related topics are available at http://www.magweb.com