These rules were developed as a result of a growing realization that skirmish wargamers have far too great a control of what their "units" do than most other wargamers. Equally they also have a far greater knowledge of the behavior of their opponent's "units" than conventional garners. For"unit", read figure, or character as we prefer to call them.

These rules were developed as a result of a growing realization that skirmish wargamers have far too great a control of what their "units" do than most other wargamers. Equally they also have a far greater knowledge of the behavior of their opponent's "units" than conventional garners. For"unit", read figure, or character as we prefer to call them.

For example, if a skirmish gamerorders his character to fire, aim, advance or carry out an action he knows that the order will be obeyed. In the more conventional game this certainly would be unlikely to exist and certainly in real warfare it would not. The carrying out of the order would depend upon the type of troops being given the order, their morale state, the quality of their officers and a host of otherfactors. These are all rolled into what are usually described as Morale rules.

Yet we are more concerned with individuals, who are more likely to act in individual and unpredictable ways. In a real battle a commander of a small unit cannot be sure that each of his men will act on accordance with his orders, even though he knows they are the right ones in the situation. Any orders he gives will be subject to the physical and mental make-up of the recipients. Bravery, fear, enthusiasm, terror, clumsiness and skill will all affect the actual response.

But in our games this was not the case. We order a characterto aim and fire and he does so; we order a characterto run across the street (under fire, probably) and he does so; we order a character to stand and fight and he does so. I n fact all our characters have just about the same mental traits, it seems; they are all equally brave, intelligent, and heroic! In real life it would be rather different I suspect. A man might be too scared to dash across that street, or too excited to take such careful aim, or too confused to stand fast.

This over extensive knowledge and certainty also extended to the effect of wounds. When a character is hit we consult the Wound Table and this tells us exactly how many phases the character will be out of action. Whilst this is useful if it is your character, it is even more useful if it was your character which fired the shot, because it lets you know just how long the character will be out of the game and thus how longyou can ignore him. No such certainty could be possible in a real fight. Even if the other player does not know whether the character is a Vet, AV or Nov, the span of minimum and maximum is known.

So, whilst our rules covered in considerable depth the physical abilities of our characters through Firing, Fighting, Throwing factors and so on, there was an important part of the overall make-up of a man which was largely ignored, that of the Mental abilities. What we felt we needed was a rules mechanism which would reflect all this. We did attempt something along these lines in the very first edition of our rules, the Western Gunfight rules, which had Nerve Initiative Tests. We dropped them because of the very short timescale we had adopted but it was obvious that something along these lines was needed and so we decided to develop something. Mike Bell was the prime mover in all this and produced some ideas.

These attempted to expand the existing game mechanics by introducing a range of mental and physical traits which would add a new element of FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt) into the game and in so doing bring in greater reality (in so far as any game reflects any element of reality, of course) too. Certainly the ideas introduced additional frustration and fun!

The principles are simple - you can tell your character to do anything you want to, just as you always could, but his compliance is no longer guaranteed. Indeed he might do just the opposite, or worse. You indicate what you want the character to do in your usual way (written orders, order cards, etc.) but then you test to see whether they obey. Let me hasten to explain thatthe aim is notto remove control bythe players entirely, but simply to introduce some uncertainty and, as a consequence, some confusion such as would undoubtedly exist in real shootouts. It is difficult to see quite why the frustration of having some of your characters blazing away at a target he has no chance of hitting or stubbornly insisting on takingcareful aim when a snap shot is so obviously called forshould add to the enjoyment of a game but I can assure you that it does.

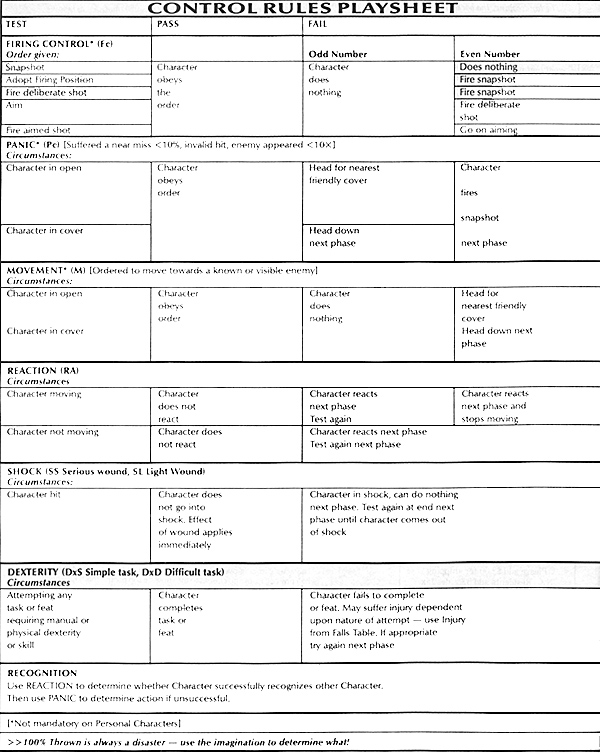

We found that Mike's original rules were rather too complicated and so we simplified them to 6 new Abilities or Factors. These are Firing Control, Panic Control, Movement Control, Reaction, Shock and Dexterity. The table shows how they work in the game but a few words of explanation may help.

First, each character needs to be given ratings for each of these new abilities or factors. The ratings are percentages, i.e., numbers in the range 1-100 (actually, 99%, as 100% is never used) and as a general principle the higher they are, the better the ability. As a rough guide to the kind of ratings to use a table is included but please do not apply it blindly. The ratings you use should reflect the traits of the character, so that, for example, a Pro (professional, veteran) might be a big brawny guy with clumsy hands and low Dexterity or a Nov (novice) might be built like an ox and have high Shock ratings.

In other words, fit the ratings to the character- I am sure you get the idea. With these new areas the old rigid Ability ratings of Pro/Av/Nov (AV = average) are less important and more flexibility is possible if you want it: if not then apply the limits as on the table.

| Ability Rating | Firing | Panic | Movement Bravery | Reaction | Shock | Dexterity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | L | S | D | |||||

| PRO | 80-99 | 80-99 | Fearless 90 | 80-99 | 40 | 90 | 90 | 50 |

| Brave 70 | ||||||||

| AV | 40-70 | 60-70 | Steady 60 | 40-70 | 20 | 70 | 80 | 40 |

| Cautious 40 | ||||||||

| NOV | 10-30 | 10-50 | Yellow 10 | 10-30 | 10 | 50 | 70 | 30 |

Firing Control

The testis simple. When the character is given orders to fire or a firing related order like Aim or AdoptA Firing Position then he throws the % dice. If the score is equal to or is less than the character's Control Factor then the character carries out the order OK. If the score is greater than the Control Factor, on the other hand, then instead of doing the right thing, i.e., what the player wanted, the character will act in accordance with his own ideas - to see what, exactly, consult the table. The actual result depends also on whether the throw was an even or odd number. If odd then the outcome is always that the guy does nothing, but if even then anything can happen.

Panic Control

With this it is events which may make the character act in certain ways. If he suffers a near miss, i.e., a shot at him is within 10% of hitting, an invalid hit, or because an enemy (or even just an unknown or unrecognized character) is within 10 yards then throw the dice. Again a score equal to or less than the factor means he is OK but a score overthe factor means he fails the test and must act as the table dictates. His actions are dependent on whether he is in cover or in the open.

Movement (Bravery)

This is not a test for all movement, only when the character has been ordered to move towards the enemy (or even towards where the enemy may be, if he does not know where they are, if you want to apply the rule that way - it is up to you). The same principles as before and again his actions depend on whether he is in cover or not. The other point to make is that the ratings are not meant to show that a Pro can only have a rating of Fearless 90% or a Nov Yellow 10%. Most Pros would probably be Cautious 40% - that is how they survived long enough to become Pros! So you can have Fearless Novices and Averages, and Yellow Pros. The table is just really showing what each factor of the Bravery ratings should have for Movement test purposes.

Reaction

This is a new idea which enables the old fixed reaction times related to the Professional/Average/Novice categories. Each character has a Reaction Factor so that the reaction time he will take is no longer predictable. When a situation arises in which, with the original rules, the character would spend phases reacting then the Reaction Test is taken instead. If the score is equal to or less than the characters Reaction Factor then the character does not react, or rather reacts immediately and can do what the player likes the next phase. If the score is greater than the Control Factor, on the other hand, then the character spends the next phase reacting and then throws again at the end of the phase to see whether he stops reacting or contin u es for another phase and soon until he succeeds in throwing below his factor.

Shock

The fixed No-Action times caused by wounds are replaced by 2 Shock Factors, one for Serious Wounds (S) and one for Light Wounds (L ). When a character is hit, throw the dice. If the score is less than or equal to his factor then he ignores the stunning effect of the wound and does not fall down. The deductions from firing, movement and fighting still apply, of course. The rule can even be applied in the case of a hit which kills the character, i.e., a Dead result on the Firing Table! The difference with Dead, however, is that he throws each phase to stay on his feet and when he goes down he stays down - and it can be most disconcerting having someone who has suffered a mortal wound staying on their feet for a couple of phases and firing back.

Dexterity

This is intended to bring uncertainty and delay into the clever little things that players sometimes have characters do. There are 2 factors, one for Simple Actions (S) and one for Difficult Actions (D). As to what actions fall into which category we leave up to you, as they are all fairly obvious we feel. Dexterity can be used to replace all fixed action times specified in the rules but we suggest that you use a minimum and maximum approach ratherthan allowing things to be done too fast than would be possible or to take ridiculously long.

Recognition

This is an extra shown on the table just in case you want a simple rule to cover those situations which arise in which recognition, of friend or foe, is important and would not be automatic. We use it to cause consternation, e.g., when a character charges into a dark room which could contain either friends or enemies, or just innocent bystanders. I am sure you get the idea.

By way of added fun when 100 is thrown it is always some kind of disaster. There can be no rules for this, it is a case of using one's imagination to the full! As an example, with Dexterity it could be that if the throw was for the character climbing over a balcony and dropping to the ground then the balcony collapses and crashes to the street on top of him (this happened to Kid Colwill in a game just the other day).

Why not give these rules a try in your next Old West skirmish? You will need to allocate the extra abilities and factors but it will only take a minute or two and once done they can be kept like all the other ratings and used every time. We have found that they add a lot of enjoyment to our games and use them all the time. Mike Bell gets cursed every time the Control rules bring some well planned move to a halt or to disaster, but we would not be without them now. They have transformed our games by introducing real unpredictability - and made them even more FUN!

If any of you Old West Skirmishers in the States have any queries or comments on these Control Rule ideas then please drop me a line. An IRC would be appreciated but is not essential - I enjoy writing to fellow enthusiasts. We had some good letters after the SCMT article and we are always delighted to hear from others who share our interests.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 5

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1989 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles covering military history and related topics are available at http://www.magweb.com