The scope of this evaluation is going to be limited to the period of 1808-1815. Though there were actions in the Caribbean and a brief action in the Netherlands before 1800, the principal campaigns of the British Army fall between 1808 and 1815, so there is little point, and less supporting data available to me, to justify attempting to evaluate the army for the earlier periods.

The scope of this evaluation is going to be limited to the period of 1808-1815. Though there were actions in the Caribbean and a brief action in the Netherlands before 1800, the principal campaigns of the British Army fall between 1808 and 1815, so there is little point, and less supporting data available to me, to justify attempting to evaluate the army for the earlier periods.

Defense of Hougoumont by the Coldstream Guards Flank Company at Waterloo. Froma watercolor by Denis Dighton (1792-1827). Reprinted with permission of the National Army Museum, London.

When studying history it is desirable to have as neutral an attitude as possible towards the subject and to enter that study with as broad a mind as possible. However, that is not always possible and everyone has perceptions or attitudes that slan ttheir understanding of the topic at hand. When preparing this analysis I too had several biases, not in the terms of Anglophilia or Anglophobia, but attitudes towards the merits of various units within the British Army vis-a-vis one another. The mathematical analysis that is distilled and presented here changed my perceptions tremendously and may well be rather startling to you, the reader. I was fortunate enough to come into possession of a large number of official, historical records of great detail and relevance to the morale of the British Army. What came out the far end of this study is not what I expected, nor is it the fruit of a biased analysis. It is the simple distillation of British documentation.

The official documentation used in this study was the official listing of deaths, desertions and stations. It proved very enlightening insight into the morale of the British Army. This listing contained those statistics for every cavairy regiment and infantry batailIon, for the British Army between 1 811 and 1813. No one can argue that the desertion rate of a unit is not directly related to its morale. Obviously, if the soldiers are happy they won't desert. And, conversely, the worse the regiment's morale, the more men will desert.

These listings of desertions revealed two facts, one obvious, and one startling. The obvious fact is that the location of the unit has a lot to do with its desertion rate. The startling feature is that the highest desertion rates, in ascending order, are found in England, Scotland and Ireland, while the lowest are in Portugal and Spain, where there was a war, and in India.

There is also some correlation between desertion rates, duty station and the type of unit, i.e., Scottish regiments had very high desertion rates when in Scotland. I suppose they want to go home.

A good example in point is the 4/1st Foot Regiment, or Royal Scots. In 1811 it had 138 deserters, while posted in Scotland. In 1812 it was still posted in Scotland and had an even higher desertion rate (202 men). This means that its morale, working on the assumption that the desertion rate is directly proportional to the unit's morale, was the second worst in the entire army. Only the Duke of York's Greek Light Infantry had more deserters - 215 and the Chasseurs Brittaniques, formed with French POW's and deserters, came in third with 171 deserters. The assigned strength of the 4/1 st-infantry Regiment was about 71,336, which means that it had a desertion rate of at least 15%! As the actual strength of the unit was less than that the desertion rate was higher than 15%.

In 1813 the 4/1 st was moved to Germany, but it still had 126 men desert. Its established strength in 1813 was still 1,336, which means that at least 9%of its men deserted. No doubt it would have been higher if the unit had not moved to Germany and the war. I

Another point that should be considered is the question about desertions from such places as Malta, Jamaica, Mauritius, etc. Here we have soldiers on small islands, often in the middle of nowhere. One could logically ask, "Even if they did desert, where could they go?" However, when one examines the records of desertions one finds that the deserters did find ways of going some place which they hoped was better than where they were.

In 1812 we find the 1/72nd and the 86th Foot Regiments posted to islands in the Indian Ocean. The 1/72nd suffered only one deserter, while the 86th had 22 deserters. Even in the middle of the Indian Ocean they seemed. to feel that there was sufficient means and reason to desert.

Furthermore, in examining the records, there appeared to be little correlation between units that were of a specific ethnicity and their morale, unless one considered the duty station. Therefore, suggestions that "Highlanders" or "Fusiliers" should have higher morale ratings or Irish units should have lower ratings appears to be completely without justifiable foundation. The correlation between all units, and their duty stations was far higher.

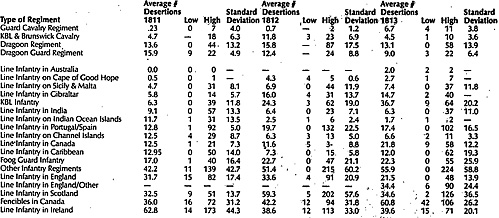

The following table is a listing of unit types by year, showing the average number of desertions per. unit, the high and low desertions per any unit in that category, and, in the case of the line infantry, a breakdown by duty station. This data shows some pretty startling facts.

In examining this chart it is interesting to note that in 1811 the average number of desertions was higher for the three guard regiments than it was fo rthe line regiments in Australia, the Cape, Sicily, Malta, Gibraltar, India, in the middle of the Indian Ocean, in Portugal on the Channel Islands, in Canada and on the supposedly disease ridden islands of the Caribbean. Also the KGL had a lower average annual number of desertions. What is really shocking is that the foreign regiments had an average desertion rate that was lower than line infantry in England, Scotland and Ireland!

I don't understand that the punishment for deserting in the face of the enemy was any more than the punishment for deserting while in England, so it is unlikely that it was a matter of the potential punishment inhibiting desertions. In fact, I would suspect that the English soldiers actually appear to have liked going to war!

In combining and analyzing the desertions for the period of 1811 through 1813 and ranking them in ascending order we find the following statistical relations:

| Unit | Mean Number of Desertions | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Guard Cavairy Regiment | 3.2 | 3.0 |

| KGL & Brunswick Cavalry | 7.6 | 6.3 |

| Dragoon Guard Regiment | 12.6 | 7.4 |

| (Light) Dragoon Regiment | 14.4 | 15.0 |

| Line Infantry | 19.2/year | 24.0 |

| Foot Guard Infantry | 20.7 | 20.8 |

| KGL Infantry | 23.4 | 20.3 |

| Fencibles in Canada | 41.4 | 28.1 |

| Other Foreign Infantry Regiments | 52.9 | 55.2 |

Of the two statistical reviews, this one is probably the more useful to the gamer because it shows the general morale levels of the British infantry over a three year period of constant warfare. It combines and evens out the effect of units being in garrison in England and Ireland with those units actually in combat in the field giving a good, broad view of the overall morale of the British Army. It is with this analysis that the basic morale status of the British Army has been determined, with modifications based on Wellington's correspondence.

The most interesting thing to note is that the British Guard, Line and KCL infantry have substantially the same annual level of desertions. This strongly indicates that there should be no significant difference in the morale of these units. Indeed, it strongly supports the contention that the British Guard were no better or worse than the line. Their biggest single advantage was that in the field they generally had a larger battalion field strength. That is to say they often fielded over 1,000 men actual head count, in contrast to the theoretical establishment.

To support this contention, one has only to review the cavalry desertion rates. Notice that the three guard regiments have an almost imperceptible desertion rate. Indeed, the deserters are almost entirely from the "Blues". The 1st and 2nd Life Guards have no desertions Tor several years.

Not surprisingly it shows the Dragoon Guards and tile Dragoons having approximately the same level of desertions and, subsequently, the same morale level. The slightly lower desertion rates of the KGL and Brunswick Oels cavalry can easily be explained by the probably social standing of the men. On the whole it is more likely that those troopers of the KGL and Oels were of a better birth, i.e., not peasants, because they were members of a mounted unit. That being the case' they would have more to fight for visa-vis the lifting of the Napoleonic yoke from their homeland.

Having established these few points it would now seem appropriate to prepare some evaulations for the various units of the British Army. In seeming contrast to my French article, where I made a point of justifying why one could not give a single unit the same morale rating for a period of 23 years, it is my contention that for the short, seven year period from 1808 to 1815 where data is held on three of those years, one can give a single rating and be reasonably justified in doing so. Especially when one is working with desertion data for the central three of those seven years. If Wellington's correspondence provided data that modified a rating based on morale a note has been added to provide an explanation of why the morale is different than the desertion rate might otherwise justify. On that basis the following evaluations are made:

Cavalry Unit, Class, and ACE

1st Life Guard Regiment Guard 30/Battle

2nd Life Guard Regiment Guard 30/Battle

Regiment of Horse Guards Grenadiers 28/Battle

1st Dragoon Guard Regiment Elites' 24/Battle

2nd Dragoon Guard Regiment Crack Line 18/Battle

3rd Dragoon Guard Regiment Grenadiers 28/Battle

4th Dragoon Guard Regiment Elites 24/Battle

5th Dragoon Guard Regiment Elites. 24/Battle

6th Dragoon Guard Regiment Elites 24/Battle

7th Dragoon Guard Regiment Elites 24/Battle

1st Dragoon Regiment Grenadiers 26/Battle

2nd Dragoon Regiment Elites 24/Battle

3rd Dragoon Regiment Elites 24/Battle

4th Dragoon Regiment Grenadiers 26/Battle

5th Dragoon Regiment Disbanded

6th Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Battle

7th Light Dragoon Regiment \teleran Line 16/Non-Battle

(in 1813 this should be raised to Crack Line 20/Non-Battle as a result of performance, in several actions.)

8th Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

9th Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

10th Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

llth Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

12th Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

l3th Light Dragoon Regiment Elites 24/Non-Battle

l4th Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

15th Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

16th Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

17th Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

18th Light Dragoon Regimert Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

19th Light Dragoon Regiment Veteran Line 16/Non-Battle

20th Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

21st Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

22nd Light Dragoon Regiment Elites 24/Non-Battle

23rd Lod Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

24th Light Dragoon Regiment Crack Line 20/Non-Battle

25th Light Dragoon Regiment Elites 24/Non-Battle

Foreign Cavairy

Brunswick Oels Cavairy Elites 22/Non-Battle

KGL 1st Dragoons Elites 22/Non-Battle

KGL 2nd Dragoons Elites 22/Non-Battle

KGL 1st Light Dragoons Elites 22/Non-Battle

KGL 2nd Light Dragoons Elites 22/Non-Battle

KGL 3rd Light Dragoons Elites. 22/Non-Battle

Guard infantry

1/1st Foot Guard Regiment Elites

2/1st Foot Guard Regiment Grenadiers

3/1 Foot Guard Regiment Guard

1/Coldstream Foot Guard Guard

2/Coldstream Foot Guard Elites

1/3rd Foot Guard Regiment Guard

2/3rd Foot Guard Regirnent Elites

Line infantry

Except as noted, all line infantry is rated as "crack line". Those units which demonsrated 3 or fewef desertions for the entire period 1811-1813 were given an "elite" status. Those who had rates of desertion averaging about 40 per year were given a "veteran line" status; those with W100 per year were given a "conscript line status, and those with over 100 were felt to qualify as landwehr.

4/1st RoF Landwehr

2/6th RoF Elites

1/7th RoF Elites

1 3th RoF Elites

1/l4th RoF Elites

2/14th RoF Veteran Line

1/15th RoF Elites

16th RoF Veteran Line

2/21st RoF Veteran Line

2/24th RoF Veteran Line; Conscript Line - December 1812 through 1813 only. In December

1812 this battalion was stripped of its privates and the cadre returned to

England to recruit.

2/25th RoF Veteran Line

2/26th RoF Conscript Line

3/27th RoF Landwehr

29th RoF Veteran Line

1/30th RoF Elites

1/31st RoF Elites

2/32nd RoF Veteran Line

33rd RoF Veteran Line

1/34th RoF Elites

2/34th RoF Veteran Line

2/36th RoF Veteran Line

1/37th RoF Conscript Line

2/38th RoF Elites; Conscript Line - December 1812 through 1813 only. In December

1812 this battalion was stripped of its privates and the cacke returned to

England to recruit.

1/40th RoF Elites

2/40th RoF Veteran Line

2/41st RoF Veteran Line

1/43rd RoF Elites - repeated superior performance in action in 1811 and 1812.

2/43rd RoF Veteran Line

1/47th RoF Elites

2/49th RoF Elites

1/52nd RoF Elites - repeated superior performance in action in 1811 and 1812.

2/52nd RoF Veteran Line

1/53rd RoF Elites

54th RoF \teleran Line

55th RoF Veteran Line

1/56th RoF Elites

2/56th RoF Vetesan Line

2/59th RoF Conscript Line

5/60th RoF Veteran Line

2/61st RoF Veteran Line

1/62nd RoF Elites

2/62nd RoF Veteran Line

1/66th RoF Elites

2/66th RoF Veteran Line

1/67th RoF Elites

2/69th RoF Veteran Line

70th RoF Veteran Line

2/71st RoF Conscript Line

1/72nd RoF Elites

1/73rd RoF Elites

2/73rd RoF Conscript Line

74th RoF Conscript Line

2/79th RoF Veteran Line

2/84th RoF Landwehr

1/85th RoF Veteran Line (1810-1811 only); This battalion had its entire officer cc" replaced in 1811 because of a

high level of quarrels and duels amongst the officer cadre.

2/87th RoF Veteran Line

1/89th RoF Elites

1/90th RoF Elites

2/90th RoF Conscript Line

2/91st RoF Landwehr

1/94th RoF Veteran Line

3/95th RoF

Foreign Infantry

Royal Africa Corps Veteran Line

Creek Light Infantry Larxhvehr

de Meufon Regiment Veteran Line

Cape Regiment Veteran Line

de Roll Regiment Veteran Line

Maltese Provincials Veteran Line

Watteville Regiment Veteran Line

1/Italian Volunteers Veteran Line

Dillon's Regiment Landwehr

2/ttalian Volunteers Trained Militia

Chasseurs Brittainiques Trained Militia

3rd Italian Regiment Trained Militia

Royal York Volunteers Veteran Line

Calabrian Corps Veteran Line

Royal Corsican Rangers Conscript Line

Bourbon Regiment Conscript Line

Sicilian Regiment Veteran Line

1st Greek Lt. Infantry Untrained Militia

Royal York Rangers Landwehr

2nd Greek Lt. Infantry Untrained Militia

Royal West India Rangers Veteran Line

l0nidn Greek Infantry Conscript Line

Brunswick Oels Infantry Conscript Line

KGL Infantry

KCL 1st Light Battalion Veteran Line

KGL 4th Line Battalion Crack Line

KGL 2nd Light Battalion Veteran Line

KGL 5th Line Battalion Veteran Line

KGL 1st Line Battalion Veteran Line

KGL 6th Line Battalion Crack Line

KGL 2nd Line Battalion Crack Line

KGL 7th Line Battalion Crack Line

KGL 3rd Line Battalion Crack Line

KGL 8th Line Battalion Crack Line

New World Fencible units

Canadian Fencibles Landwehr Glengary Fencibles Landwehr

Newfoundland Fencibles Conscript Line

Nww Brunswick Fencibles Conscript Line

Nova Scotia Fencibles Conscript Line

Canadian Voltigeurs Conscript Line

The response to the article evaluating the French Army and the requests for similar articles for other armies had been phenomenal. Initially I passed on those requests because of the problems of gathering sufficient data. The material used in the French article was gathered over a period of 9 years and parallel research for similar articles would be prohibitive. Fortunately, I chanced to receive copies of the desertion records in the spring of 1988 that permitted me to undertake such an articles for the British. These came from Warren Worley of Olvieda, Florida. These documents, coupled with Gurwood's Wellington's Correspondance have made this study possible.

This article will probably be greeted with howls of "Anglophobia", especially after my previous article on rating the French Army through, the Napoleonic wars. It is not so, even though I will admit that I have been unjustifiably accused of "Francophilia" by no less than David Chandler when he wrote the foreword for my book "Napoleon's Invasion of Russia, Presidio Press, 1988.

I would repudiate both claims. Both that book and especially this article are based on hard fact. The article is drawn from parliamentary records and Wellington's correspondence. If quoting those documents is "anglophobia" so be it. This article is based on modern statistical analysis, the tools of my profession.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 4

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com