Provincial Regiments were raised in the British North American colonies during the 1753-64 War because even empire have priorities on their manpower. Britain's attention was mostly focused elsewhere during this era, and the colonists would have to supplement the regulars. This particular article concerns the Virginia Regiment, raised in that colony in 1754. To be accurate, Virginia raised three regiments, the first being down-rated to a set of independent companies before being re-raised as a regiment, and the second regiment being mustered in and mustered out in 1758 before being able to accomplish much (Elting, pg. 20).

The Virginia provi ncials were disti nct from the militia, as were provincials in other colonies. Militiamen were supposed to supply their own arms and would not serve outside of Virginia (Titus, pg. 56). There were also problems with militia service within Virginia. Most of the population was concerned with events on the coast or in Europe; few were greatly concerned about the frontier. The gentry did not want to pay for a militia army, and the individual militiaman really couldn't leave home for long. Military service for any length of time could mean economic ruin.

Provincial soldiers, on the other hand, had uniforms (paid for by stoppages), and weapons were provided. There was a term of service, as opposed to an on-call service. Discipline was closer to the regular army than the militia. The Virginia Regiment was as near to a standing army as the Colony wanted or thought it needed.

To the bad, being a provincial was never popular. Because coastal Virginia could not be convinced of the need there were never enough volunteers. Conscription was eventually resorted to, but failed to provide enough potentially good soldiers. Desertions were always a problem, particularly as pay was much lower by civilian standards, and pay was often late. To the good, Virginia provincials did well in battle, as noted by some British generals (Titus, pgs. 50-235).

The first Regiment consisted of six companies with enough recruits for five of the six in mid-1754. Officers appointed for the unit included Joshua Fry as colonial and George Washington as lieutenant-colonel. Despite this reasonably strong start, the Regiment officially dissolved into ten independent companies in October 1754. Independent companies were perhaps felt to be more flexible, probably less expensive, and better suited for conditions in Virginia. Other colonies possessed independent companies, probably for the same reasons.

This organization did not last. The Regiment re-incorporated in 1755, this time with sixteen companies and Washington as colonel. Its uniform differed markedly from the 1754 version. Enlisted men in 1754 were to wear their own clothing at first. This did not last. Citizens who could provide sufficient suitable clothing did not become private soldiers; those who could not tended to be in the ranks. The uniform adopted to solve this difficulty was a scarlet coat and breeches of the least expensive cloth and a very basic cut - no lapels and no distinctive markings at collar, cuff, and buttonholes. Officers had longer coats, probably of a much better grade of material. One such officer's coat was described as a "flaming suit of laced regimentals".

For most of its service, the 1755 Regiment had navy (or very dark blue) regimentals with scarlet facings, cuffs and waistcoats. The coat was apparently shortened for enlisted men. Officers wore longer coats, with silver trim on cuffs, facings and waistcoats. Each cuff had a "pocket flap", with three points on its base, sewn on running lengthwise up the arm. Gorget and sash were in use. Officers and enlisted men wore issue silver-trimmed cocked hats (Elting, pg. 21).

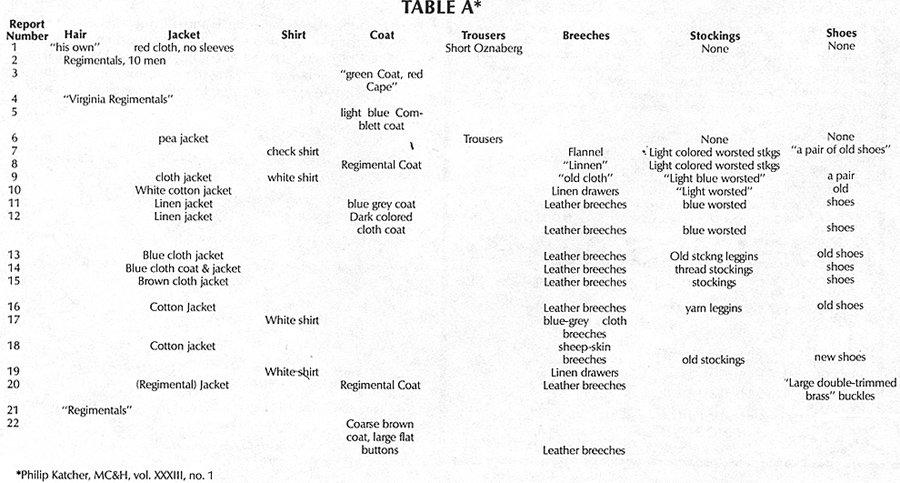

There were apparently a great many variations of this uniform, including civilian clothing, according to deserter reports published in local newspapers (Table A). At least 13 deserted with their regimentals. Others deserted in civilian coats or jackets, flannel or linen or leather breeches, trousers, and with or without shoes. Either supplies of uniforms never caught up with the numbers of recruits or enlisted men preferred their own clothing, and the officers allowed this because it reduced the regimental expenditures (always a concern in Virginia in this war). It is also a hypothesis that some deserters went to the trouble of securing civilian clothing to make desertion easier. Research has not uncovered anyone deserting from the 1754 Regiment, taking the scarlet uniform with him. The probability is that no one did, but there is no known data one way or the other.

Flags used by the 1755 Regiment followed English patterns. They had a white field, a large cross in red/scarlet, a Union flag in the left upper corner, and a wreath in the center containing the inscription "VA Regt". Copies of these flags hang in the Governor's Palace in Colonial Williamsburg.

PAINTING

One way to paint this regiment would be to choose between two "different" units, with shortened coats for enlisted men and longer ones for officers. British infantry figures for 1754-1755 should be correct, allowing for the cuff and shortened coat already described. Weapons, accoutrements, and leather items should be as for the British.

Once the preceding is allowed for, a core unit, including officers, NCO's, musicians and color party should be in the regulation uniform. Allowances should be made for "faded" coats, differences in cloth color resulting from different dyers, or uniforms made "dressier" by the individual. Some proportion of the enlisted men would almost have to be in civilian clothing. There are civilian figures on the market, and they can be drafted for regimental service.

A 1754 Regiment will be faster to paint, as a scarlet uniform, neck to knees, paints quickly. A 1755 Regiment represents one that saw more service, and looks less "British". The other items - guns, crossbelts, haversacks, and so on, should be pretty standard. The only potentially difficult part would be making any civilian figures look non-uniform and somewhat military at the same time.

USEFULNESS

The Virginia Regiment's usefulness to the wargamer will depend pretty much on what kind of gaming is preferred. The Regiment's companies were usually scattered in isolated forts, attempting to thwart enemy raiding parties. Gamers might want to paint and mount the figures for whatever set of skirmish rules is in use. Other considerations might be that this would make play awkward for anything other than a company-level game. Skirmishers also should have a better grade of painting overall because individual figures stand out. Not least, of course, skirmishing requires buying and painting fewer figures than regimental/brigade level games.

Line of battle would be the least common usage of the Regiment. It should be present in British-colonial armies for the 1754-1763 conflict, because of its historical importance. However, the Regiment on frontier service never was completely concentrated, so there should not be a lot of Virginians present in any wargaming army.

Six companies is the largest concentration of the Regiment found so far; but at the Battle of Monongahela in 1755 Virginians did better in battle than British regulars. One Virginian, George Washington, even managed the retreat of the British Army while technically serving as an unpaid aide-de-camp (Hamilton, pg. 154). You need Virginians in your British colonial army, especially in a campaign situation, as they may be the best troops for a wilderness campaign (Hamilton, pg. 15 8).

Virginian independent companies and regimental companies were present in almost every campaign south of New York, even if there was no battle at the end. There were problems of resupply, morale, desertion, and a governmental reluctance to fiscally support the Regiment. The Virginia Regiment was Washington's training ground.

There was no cavalry in Washington's portion of the War for Empire. This may be why he did not use his cavalry as effectively as possible during the Revolution. Colonel Washington did not maneuver whole armies during the 1754-1763 war, and he would have his problems from this lack of experience with Revolutionary armies. Washington's training to lead an army and his later desire for a European, formal army, as opposed to a militia-frontier organization, can also be perceived as stemming from his service with the Virginia provincials.

If this article causes anyone to add provincial regiments to an 18th Century army, then I have succeeded, and that person has a better army. It should be kept in mind that other colonies had their provincial units of cavalry, artillery, or infantry, allowing the wargamer to simulate regimental conditions while achieving more historically accurate forces.

READING LIST

Edward P. Hamilton, The French and Indian War, Doubleday and Company, Inc., Garden City, NY, 1962.

James R.W. Titus, Soldiers When They Chose to Be So: Virginians at War, 1754-1763, University Microfilms International, 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI, 1983.

Philip Katcher, Armies of the American Wars, 1753-1815, Hastings House, New York, NY, 1975.

Anonymous, A Soldier's Guide to the Virginia Regiment, Colonial Williamsburg research report, Williamsburg, VA, Feb. 22,1961.

Allan W. Eckert, Wilderness Empire, Bantam Books, Inc., New York, NY, 1971.

Philip Katcher, "Military Notes and Deserter Descriptions", Military Collector and Historian, Vol. Vol., No. 2, Washington, DC, Summer 1980.

Philip Katcher, "Military Notes and Deserter Descriptions", Military Collector and Historian, Vol. XXXIII, No. 1, Washington, DC, Spring 1981.

John F. Lowe, A Manual for the Public Magazine, Colonial Williamsburg research report, June 1972.

John F. Efling, ed., Military Uniforms in America: The Era of the American Revolution, Company of Military Historians, Presidio Press, San Rafael, CA, 1974,

Table A

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 3

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com