Though there area number of period drill regulations for artillery, there is very little readily available on the philosophy of artillery usage. The most thorough discussion of the philosophy of the use of artillery I have seen to date came, most surprisingly, from an 1816 Spanish source. In his Tratado de Artillerie, de Moria provides a number of maxims that are most enlightening. Though most of them are listed below, some were deleted because they are relevant to specific situations, rather than to the general usage of artillery.

Though there area number of period drill regulations for artillery, there is very little readily available on the philosophy of artillery usage. The most thorough discussion of the philosophy of the use of artillery I have seen to date came, most surprisingly, from an 1816 Spanish source. In his Tratado de Artillerie, de Moria provides a number of maxims that are most enlightening. Though most of them are listed below, some were deleted because they are relevant to specific situations, rather than to the general usage of artillery.

His first maxim is: "When in the sight of the enemy and when the artillery maneuvers, maneuver it with the prolong or by hand. "This ties closely with the second maxim, which is: "Artillery should be maneuvered by prolong when within range of enemy artillery and when the distance robe traversed is short, but over broken or rough terrain, or when the movement is large." It was felt that the prolong was the quickest way to move short distances and that it kept the gunners close to their firing positions. It was also felt that unless the move was significant, it was inappropriate to risk the limbered battery to the enemy fire.

The third maxim is: "When the movement of the artillery is short, the guns should be moved foward by hand. "The proling, a series of lines run out in front of the gun and used to pull it forward by hand, took a fair amount of time to rig and was not as quick over short distances.

The fourth maxim is: "When maneuvering artillery, never maneuver munitions and reserves with the brigade guns, because they complicate maneuvers."

The fifth maxim is: "The artillery should never maneuver according to the movements of the infantry. - By failing to operate in close conjunction with the infantry columns, they may maneuver such that there is insufficient space between them for the artillery to deploy. A single gun was considered to occupy the space occupied by the smallest maneuvering element of an infantry battalion. If the infantry formed without consideration for the artillery it would be crowded out and unable to deploy.

The eighth maxim is: "Batteries should endeavor to take up positions which enfilade the enemy, or at least fire on him obliquely. "This increases the killing power of each shot by maximizing the depth of the enemy formation that it penetrates. There are recorded instances of a single ball passing through a company on an enfilade shot that killed ten or more men. The impact of a shot into the flank of a dense formation was devastating.

The ninth maxim is: "Never put your batteries in front of your troops, nor behind them on slightly raised elevations." Artillery posted before the infantry was felt to increase the target for the enemy, as well as impede or break the movements and order of the troops. If the artillery is above the infantry and firing over their heads, they "torment" the infantry with the noise of the firing and hurt them with the spillage of the cartridges and short rounds.

The tenth maxim is: "Do not position the batteries until it is time to commence fire. " The intention here is to prevent the enemy from altering his dispositions when he knows the positions of the opposing artillery.

The eleventh maxim is: "Always conceal a portion of your artillery from the enemy. "This speaks both in the sense of maintaining a reserve and allowing yourself to have the enemy commit himself to a maneuver without knowing of the threat of artillery that will take his maneuver under fire.

The thirteenth maxim is: "Always position batteries on the flanks such that they can fire on the enemy cavalry when it advances."

The fourteenth maxim is: "If artillery is assigned to protect your cavalry, the number should be large enough to ensure victory and it should, if possible, be posted in a position that is inaccessible to the enemy cavalry. "

The sixteenth maxim is: "When the artillery is posted before the main line of battle it is necessary to support them with either grenadier companies or complete battalions."

The seventeenth maxim is: "The artillery pieces in a battery should be positioned ten paces apart. If the enemy threatens to enfilade the battery one gun maybe advanced in front of the others." I his maxim establishes the Spanish interval between guns. The movement forward of one gun is intended to minimize the impact of an enfilade by enemy artillery.

The nineteenth through twenty second maxims are closely rafted. They are as follows:

19. "When the position or order of battle is defensive, position the heaviest caliber guns such that they cover the most likely avenues of enemy advance. The smaller caliber guns should be held in reserve so they can be sent where they are needed."

20. "The major portion of the heavy artillery should be posted where it protects those portions of your forces which are exposed to the enemy.

21. "Always post a heavy battery in a fortified position which covers one wing or the center of the enemy's line.

22. "Light artillery, not heavy artillery, should always accompany an attack or rapid movement."

These maxims basically state that the heavy artillery is best used defensively. It is too difficult to maneuver with ease and will embarasse maneuvers or simply cannot advance quickly enough to support an attack or counter attack. It is possible that this is heavily influenced by some pecularities of the Spanish army which was notoriously short of horses. Because of its immobility the Spanish invariably lost most of their artillery in every battle they lost to the French between 1808 and 1814.

The idea of positioning the heavy artillery on the most likely avenues of enemy advance is simply the most rational use of it. If it is difficult to maneuver, position it where it can be Used effectively and with the least requirement for repositioning.

The twentythird maxim is: "Since the effect of artillery can be decisive, it is necessary that the batteries be strong, that their fire protects themselves and that their fire be crossed."

The twentyfourth maxim is: "Artillery should never abandon the infantry and, similarly, the infantry should never abandon it." Neither is able to withstand the enemy without the support of the other. Therefore it is logical that they remain closely tied to one another.

The twenty fifth and twenty seventh maxims are closely related. They say, 25. "The conservation of munition should be one of the major objectives of the artillery officer." 27. "The first of all the regulations for the service of artillery is to economize artillery for the essential and decisive moments."

In view of the limited stores carried with a battery, ranging from 100 to slightly over 200 rounds, depending on the nation involved, a battery can shoot off its ammunition in as little as 50 minutes or as much as 100 minutes of continuous fire. The battery which has shot off all its ammunition is worthless and can't defend itself, let alone the infantry.

Maxims twenty seven through twenty nine relate to the range of fire. The twenty seventh maxim says, "Do not commence fire at a range of greater than 450 toesas (2,700 yards) from the enemy."

Long range fire is uncertain and inefficient. Unless an excellent target presents itself, long range fire can be little more than a waste of munitions.

The twentyeighth maxim says, -Between 450 toesas (2,700 yards) and250 toesas (1,500) fire ball slowly. If no enemy columns are available for fire, fire still more slowly. "

The twenty ninth maxim says, "Between 250 and 130 toesas (1,500 - 780 yards) fire large cannister, or if able to fire enfilade or against columns, fire ball at a rapid rate."

The thirtieth maxim says, "Under 130 toesas (780 yards) fire small cannister. Do not fire ball unless you have an exact enfilade of the enemy line or unless friendly troops are very near the line of fire. The rate of fire should be precipitious. "

The thirty first maxim is: "If you do not have cannister, continue to fire ball until the enemy is 90 toesas (540 yards) from the battery and then fire bags of musket balls. "

The thirty seventh maxim speaks of howitzer fire. It says, "Howitzers may begin firing at a range of 600 toesas (3,600 yards) only when the enemy is maneuvering at that distance, and should not use cannister untif the enemy is within 150 toesas (900 yards).

The most significant maxim is the thirtysecond. It speaks of target selection. It says, "The primary target of the artillery is the enemy troops and not his artillery. "To dedicate one's batteries solely to counter battery is a -waste of ammunition" that "seeks in vain to achieve its objective."

Even if the counter battery were successful, what has it achieved if the enemy's forces have overthrown your own? Counter battery was strongly discouraged, but was acceptable only if it was necessary to support and defend your own troops.

In his discussion of the use of artillery in battles, de Morla states that "the principal and unique objective of the artillery in battles is the protection of the troops supporting their maneuvers and attacks, and the destruction of the obstacles which oppose them..." ' The treatise goes on to advocate that artillery be positioned in the heads of infantry columns when they attacked, so that they might, with their fire, soften the enemy and prepare him for the infantry assault.

In the regulation for horse artillery written by General Kosciusko in 1800 there is a section on the philosophy of the usage of artillery. Kosciusko says, "The use of artillery in battle is not against the artillery of an enemy, for that would be a waste of power, but against the line of the enemy in a diagonal direction when it is destructive in the extreme. - Though he doesn't provide reasons, Kosciusko clearly states that counter battery is not to be done.

Kosciusko says that the tactics of the period "have established it a rule that only a part of the artillery shall be ever engaged; but then this party by being constantly supported from the park and that park, again supported from a reserve at a distance, is kept up in full vigour and is as entire in all its parts at the endof the action as it was at the commencement of it; two-thirds of the artillery is therefore always out of danger, and as fast as any piece becomes injured from any cause whatever, it is instantly replaced by a perfect one, while the injured piece, if sucseptible to repair, is in the way of being refitted in the rear, totally unannoyed by the enemy, so long as the front keep their ground."

"By keeping the artillery on the flanks instead of (the older practice of) mixing it in the line (of battle), it never can impede the movements of the latter, which are totally independent of it; on the other hand, when artillery is placed in the center, the movements of the line, being of a different nature from those of the artillery, can never accord with them; the pieces are therefore always in the way and the movement, whatever it may be, is in some way or another by them, and they by the troops."

Further philosophical considerations for the tactical employment of smoothbore artillery are found in the Handbook of Artillery issued for the U.S. Army in 1863. Much of its guidance supports that of the Spanish treatise.

It says that artillery should never be used in numbers less than two guns operating in a mutually supporting section. Like de Moria's thirty-second maxim, it states that counter battery is not productive and should only be undertaken "when (the enemy's) troops are well covered and his guns exposed, or their fire very destructive. Their fire should be directed principally against columns of attack, and masses, or upon positions which are intended by be carried."

In concert with de Morla's comments about the conservation of ammunition, the Handbook states that, "Upon no account; ammunition should be at all times be carefully husbanded, particularly at the commencement of an action, as the want of it at the close may decide the fate of the day; it should also be sparingly used in skirmishes and minor affairs, especially when at a distance from supplies or in anticipation of a general reserve."

The employment of artillery reserves should be "When a particular point of the fine requires additional support, a favorable position is to be seized, an impression has been made on the line by the enemy, a forward or retrograde movement is it) contemplation, or when a determined attack is to be made on him, then the reserve should come up and take part in the action; and it is of the utmost importance that this should be done as expeditiously as circumstances will permit.

Artillery reserves were to be placed, "In the rear with the second line, out of the range of shot, and as little exposed as circumstances will admit, but always in such a position as to have ready access to the front or rear."

When supporting infantry in square, the Handbook states, "When infantry are formed in -squares to resist the charge of cavalry, the guns should be placed Outside the angles of the square, the limbers, horses, etc., inside. Should the detachments be driven from their guns, they will retire into the square, after discharging their pieces, and taking with them the sponges and other equipments; the moment the enemy has retired, they recommence their fire. Supposing the infantry formed in echelon of regimental squares, and that the time or small extent of the squares, would not admit the limbers, etc., being placed inside, then the wagons and limbers should be brought up with their broadsides to the front, so as to occupy, if possible, the space between the guns, leaving no intervals for the cavalry to cut through; the prolonge or drag ropes might also offer an effectual momentary impediment to them, if properly stretched and secured."

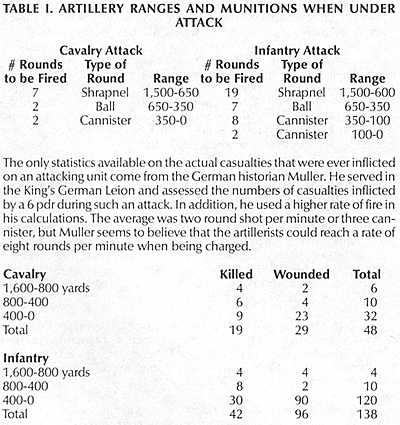

The Handbook of Artillery as well as the Madras Artillery Manual of 1848 provide scenarios for the use of artillery against advancing cavalry or infantry. Surprisingly, the two tables are identical and because of the lack of significant innovation in the world of artillery, they are probably very representative of the Napoleonic period. The following table shows the ranges and ammunition for use when the battery was under various attacks.

The only statistics available on the actual casualties that were ever inflicted on an attacking unit come from the German historian Muller. He served in the King's German Legion and assessed the numbers of casualties inflicted by a 6 pdr during such an attack. In addition, he used a higher rate of firein his calculations. The average was two round shot per minute or three cannister, but Muller seems to believe that the artillerists could reach a rate of eight rounds per minute when being charged.

The only statistics available on the actual casualties that were ever inflicted on an attacking unit come from the German historian Muller. He served in the King's German Legion and assessed the numbers of casualties inflicted by a 6 pdr during such an attack. In addition, he used a higher rate of firein his calculations. The average was two round shot per minute or three cannister, but Muller seems to believe that the artillerists could reach a rate of eight rounds per minute when being charged.

| Cavalry | Killed | Wounded | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,600-800 yards | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| 800-400 | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| 400-0 | 9 | 23 | 32 |

| Total | 19 | 29 | 48 |

| Infantry | Killed | Wounded | Total |

| 1,600-800 yards | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 800-400 | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| 400-0 | 30 | 90 | 120 |

| Total | 42 | 96 | 138 |

In his book, The Face of Battle, John Keegan says that a smoothbore cannon could keep its front clear of attacking troops with its fire. B.P.Hughes, in his book Firepower supports this. There is certainly no doubt that if a single gun could maintain the rate of fire indicated above, their front would be clear of any attacking troops.

FRENCH ARTILLERY USAGE

During the Revolutionary Wars the French used whatever artillery they had wherever they needed it. Batteries were distributed amongst the infantry in an infantry support role and often employed by sections. Indeed, individual batteries might have two different caliber cannons, in addition to their assigned howitzers.

After 1880 the battery's equipment was standardized and it was the general practice of the French to assign at least one battery per infantry division. This was generally a foot battery, but they often attached horse artillery to the infantry divisions as well. The divisional artillery was always an 8 pdr or 6 pdr battery. Horse artillery was generally assigned to the cavalry formations and, during the Revolution, consisted of 8 pdr guns. The use of 4 pdr regimental artillery continued until 1805.

The 12 pdr batteries were assigned on a corps level in the artillery reserve. In addition, the corps reserve, depending on the availability of equipment, could contain a number of light foot batteries or horse batteries.

Though banished earlier, in 1809 Napoleon decided that the regimental artillery should he re-established and by 1812 most infantry regiments had it again. In 1812 it became a standardized practice for the divisional artillery to consist of a foot and a horse battery. Equipment and horse shortages made this practice difficult to continue through 1813 and 1814, hut, when possible, this practice continued.

Napoleon, being an artillery officer, made his single biggest tactical contribution in the use of artillery. He devised the concept of the "grande batterie", which was a massing of as many as a hundred guns on a single section of the battle line. The object of these guns was to shred the enemy line and provide a hole through which Napoleon could drive his infantry and cavalry. Table II lists a few instances of the Napoleonic grande batterie.

TABLE II: GRAND BATTERIES

- Battle : Number of Guns

Castiglione : 19 (French)

Marengo : 18 (French)

Austerlitz : 24 (French)

Jena : 42 (French)

Eylau : 60 & 70 (Russian)

Friedland : 32 (French)

Deutsch-Wagram : 112 (French)

Borodino : 102 (French)

Bautzen : 76 (French)

Leipzig : 150 (French)

Hanau : 50 (French)

Ligny : 60 (French)

Waterloo : 84 (French)

AUSTRIAN ARTILLERY USAGE

In Italy, between 1800 and 1805, the Austrian armies were not particularly large and the artillery was assigned to the various infantry divisions. However, though seemingly organized as a divisional force, in fact, it was employed on a piecemeal basis. Batteries were scattered between the brigades and even break up with gun sections being employed in the line. The Austrian Army at Austerlitz was organized such that its artillery was assigned in the same manner. There was not an Austrian tactical army reserve composed of 12 pdr guns. Regimental 4 pdr guns were used during the revolution, but appear to have disappeared around 1800.

During the 1809 campaign the Austrians assigned a 6 pdr brigade battery to every line brigade. The light brigades had either a wurst battery or a 3 pdr brigade battery. They also assigned their heavier 12 pdr batteries on a corps level as an independent reserve, indicating that they had learned from the French practices of large reserves. In 1813 these corps reserves generally consisted of a 12 pdr position battery and two 6 pdr position batteries, but in 1808 they varied considerably.

PRUSSIAN ARTILLERY USAGE

Prior to 1806 the Prussians distributed their artillery on a brigade basis. An examination of the armies under Feldmarschal Brunswick-Luneberg and Furst Hohenlohe indicates that there was little regard for what was assigned to any brigade. Some had horse batteries, others 3 pdr, 6 pdr or 12 pdr foot batteries. Surprisingly, the reserve division had less artillery than the others. With the shortness of the 1806 campaign there is little that can be determined of their usage of it, but if the actions of the Prussians during the Revolutionary Wars are examined we find the typical infantry support role. There was no indication of any operational independence, indeed the artillery was quite tied to the infantry in its maneuvering. During the revolution the Prussians had used regimental 4 pdrguns, but they do not appear after 1800.

After the 1809 reorganization no doctrine on the use of artillery was established until the issuance of the 1812 Regulation. The Prussian 1812

series of regulations all repeat a set of directions on the use of combined arms. A Prussian brigade, which was the equivalent of other nations' divisions, was standardized and theoretically equipped with one 6 pdr foot and one horse battery. The foot battery operated in two half batteries, posted on the flanks of the brigade while the horse battery remained in the rear ready to deploy to whichever flank required the additional firepower. It was to act as a brigade ready reserve force, however in actual practice the horse battery was rarely assigned.

The 12 pdr batteries were assigned on a corps level and acted as the corps artillery reserve, much as that of the French. This corps reserve also contained varying numbers of 6 pdr foot and horse batteries, depending on the equipment available.

The Prussians did not mass their divisional artillery, but had the option of forming "grande batteries" from their corps reserve should the necessity arise. However, there are very few examples of the Prussians massing their artillery and no examples of what could be called a "grande batterie".

BRITISH ARTILLERY USAGE

The British use of artillery during the Napoleonic wars is truly Wellington's use of it. He did not believe in and rarely concentrated his artillery. Wellington preferred to work with small units placed in well chosen spots, and often concealed until the critical moment. They were spread in front of the position rather than massed, and in most cases must be regarded as an infantry support weapon, rather than an independent force with aims and goals of its own.

Much of this might be attributed to the small quantities of artillery available to Wellington in the Peninsula. He was unable to provide one British battery for his eight divisions and had to depend on the Portuguese for artillery support.

RUSSIAN ARTILLERY USAGE

In early 1810, Barclay de Tolly, the Russian Minister of War, wrote the Czar a report that addressed his philosophy of artillery assignment. He said that the distribution of artillery in the infantry divisions was done on a regular and equal basis. He said that there were, "two considerations on this subject (artillery assignment): a. it is necessary that the infantry divisions are not encumbered with an excessive quantity of heavy artillery which opposes the rapidity of movements by its transportation difficulties (See Morla's 22nd Maxim); b. the heavy artillery should be judiciously distributed between the infantry divisions and the excess assigned to the artillery reserve of each army. These reserves, placed under the immediate authority of the (army) commander in chief, can be employed with great advantage at the decisive moment of a battle."

"In accordance with these considerations I have the honor to propose (to your Highness), that each corps be assigned two reserve artillery batteries, composed of heavy and horse artillery."

By the beginning of the 1812 campaign, when these guidelines were implemented, each infantry division as assigned an artillery brigade that consisted of two light (6 pdr) batteries and a heavy or position (12 pdr gun) battery. At a corps level another brigade was assigned that usually had a position battery, a horse battery and one or two light batteries. This general organization persisted through 1815.

Prior to 1810 the Russians did not establish corps artillery reserves. Artillery was assigned on a divisional level and could consist of as many as two position (12 pdr) batteries, three light (6 pdr) batteries and a horse battery. They continued the use of regimental artillery through the Battle of Austerlitz, but it is not found in their orders of battle after that.

The idea of an army artillery reserve did not exist in the Russian Army before Barclay's letter, though there were massive corps reserves. Only in the Battle of Eylau do they seem to have employed it as such. No doubt Barclay noted the destructiveness of the two Russian batteries at Eylau and the French use of artillery reserves, then chose to follow it. At Borodino a massive reserve was established, but due to the poor generalship of Kutusov and the untimely death of the artillery reserve commanding officer, very little of it was employed.

The failure of the Russian artillery reserve system at Borodino may well have poisoned the Russian Army's attitude towards the large reserves advocated by Barclay de Tolly. However, the rejection of the use of artillery reserves can also be attributed to the xenophobia of the Russian establishment. It hated Barclay because of his Scottish ancestry and opposed anything he advocated on that basis alone. They steadfastly refused the poisoning of the Russian institutions with foreign ideas.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 3

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1988 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com