This year the West Point Napoleonic Gaming Club decided to try something

new -- a campaign game. We did this for several reasons. The primary reason

was realism, for the last few years the scenarios that we have been playing

have fallen into two categories: historically based scenarios, and balanced

fictional scenarios. Neither of these categories allow for the players to see the

effects of what they do on the battlefield past the next hour or two. The

players usually know the enemy's exact location, his exact strength, morale

and organization. The players also do not have to worry about saving some of

his units for the next battle - he can blow his whole army at once.

This year the West Point Napoleonic Gaming Club decided to try something

new -- a campaign game. We did this for several reasons. The primary reason

was realism, for the last few years the scenarios that we have been playing

have fallen into two categories: historically based scenarios, and balanced

fictional scenarios. Neither of these categories allow for the players to see the

effects of what they do on the battlefield past the next hour or two. The

players usually know the enemy's exact location, his exact strength, morale

and organization. The players also do not have to worry about saving some of

his units for the next battle - he can blow his whole army at once.

On the other hand, when battles are fought in the context of a campaign game, the players have to be concerned with finding and fixing the position of the enemy before he can be truly prepared for battle. Then once he is on the battlefield, he must maintain reserves at all levels to take advantage of favorable situations as they arise, or to protect against defeat. He also cannot run his whole army into the ground in one battle, because he will very likely be fighting with those same troops the very next day. The ability to explore different facets of Napoleonic warfare, the need to accommodate the busy schedules of our members that allows us to game only about once a month, and planning the campaign game during the weekdays between table top battles are other good reasons for a campaign.

Once a campaign format was decided on, several requirements were identified as being essential to the conduct of play:

1. Forces to be used by both sides in the campaign would be restricted to those painted and available to the club (approximately four Corps per side). New acquisitions would be assigned as reinforcements as they were finished.

2. The general area of Silesia would be utilized due to the availability of appropriate campaign maps.

3. The campaign rules should remain simple and not require large amounts of bookkeeping. The purpose of the campaign, to generate scenarios for tactical play, had to be the foremost thought in the minds of the participants.

To support these unique requirements of the Military Affairs Club, a "homegrown" rules system would haveto be developed. What followed was a synthesis/compilation and development process which drew on previous experience, board game rules, and miniature campaign systems to create--the body of the West Point Napoleonic Campaign Rules.

Begin

To begin play the Commander in Chief for each side was selected, given his mission, available forces, and game equipment. The first requirement was to provide the Umpire with any organizational changes, initial deployments and the first move.

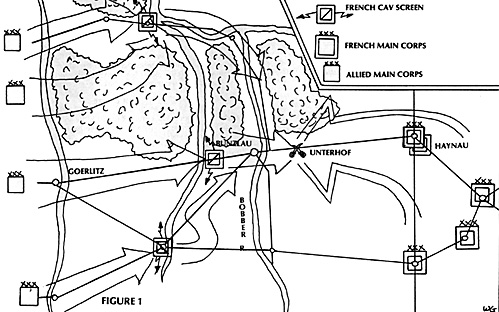

The Emperor of France, being on the defensive, opted to deploy a strong cavalry screen forward concentrated on the main approaches to the province while his main corps were concentrated to the rear in such a way as to be able to react to the allied moves (see Figure 1).

On the other side of the border of Silesia, Lord Wellington (history being discarded for equity) decided to take a broad approach, choosing to initially deceive the French by throwing out an unbroken screen of cavalry while advancing four separate axes of attack.

The protagonists thus arrayed, the campaign opened on the "First of May" (1st move). The French, through local superiority of cavalry, were able to determine the relative locations of three of the four allied corps by

the fourth day of the invasion while also inflicting some minor losses on the allied cavalry in a series of skirmishes. At this point the wily Frenchman sent out couriers with false messages to be captured and began to concentrate his forces forward on the center approach to seize the central position. I lie Allies, being unable to pierce the French screen and taking the bait of the false messages (which portrayed an exposed French unit in the vicinity of the main French concentration), continued to push their corps somewhat isolated.

As the Allies approached the Bobber River crossings the French prepared to fight the center (Prussian III Corps) of the Allied advance. With uncanny foresight the allied player began to concentrate his forces toward this point! The French cavalry screen immediately reported the start of the allied concentration while simultaneously inflicting a sharp defeat on the Prussian cavalry screen as it crossed the Bobber. Not to be dissuaded the Allies pushed the III Corps across the river against the French cavalry by deploying the infantry Brigades and a Grand Battery to seize the far side. The increased pressure of the French cavalry coupled with the defeat of the Prussian cavalry, however, effectively blinded the Allies on the Bunzlau-Haynau road at this critical junction.

The Corsican ogre, getting wind of the concentration, ordered his forces foward in a forced march to attack the exposed Prussians before they could be supported. Late on the afternoon of 7 May (7th move), portions of the four different French corps fell upon the hapless Prussian III Corps, their approach being kept from view by the cavalry screen until the attack began. With sunlight glittering off bayonets and cuirasses, and cries of "Vive l'Emperor", the French amies went in. Grim faced, the Prussians hoped to hold the vicinity of Unterhot while frantic couriers spurred off seeking support.

What follows is a description of the battle that was fought using the Empire III rules system. This description, prepared bya Cadet, was written after the battle to both entertain and enlighten members of the club.

By looking at the Battle of Unterhof, fought on 7 May 18??, we can learn many important lessons. To better understand the battle this report is in three phases. The first phase describes the movements of the French and Prussians just before the battle. The second phase is the actual fighting of the battle. Finally, the third phase views the actions of the two forces after the battle.

The most important lessons to be learned from the first phase of the battle are: the use of cavalry for screening and information gathering and their massing on the battlefield. Because of the overwhelming strength of the French cavalry screen in front of their forces, the Prussians could not find out the number and type of troops that they were about to fight. While on the other side of the field the French commander knew almost everything about the Prussian corps that he was about to attack. Once again, the reason for the different levels of intelligence can be attributed to the number and quality of cavalry that each side had on the field. Because of this information, the French commander decided to mass four of his corps to attempt to destroy the one Prussian corps. Because of the quickness of the battle (it lasted only one hour game time), there was no opportunity for forces that started off the field to enter the battlefield. The lack of mutually supporting corps is what hurt the Prussians the most; it would have taken more than a day to bring up another corps to help the one corps that would be utterly defeated.

Clearly, this opened the possibility of defeat in detail. So the lessons to be learned from the movements leading up to the battlefield are: always keep your forces within supporting distances of each other, and the force with the best and most cavalry in its screen is going to be better informed about the enemy.

THE BATTLE

THE BATTLE

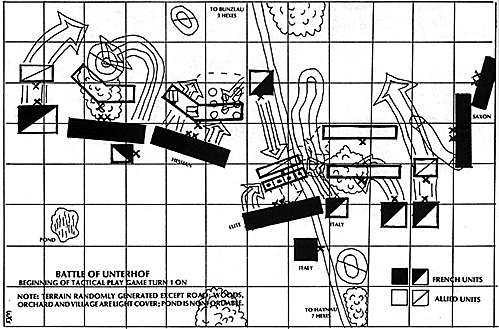

Each commander was required to write the initial orders for each maneuver element of his force before the battle. Because this was a meeting engagement, each side planned on attacking. The Prussians, lacking accurate information, planned to hold with their right flank and turn the enemy's rightflank with the combined power of two brigades of infantry, a cavalry brigade and a grand battery. The French planned to engage the Prussians frontally with his left flank and center forces, and then attack them on their leftflank and their rear with one Infantry Corps, a Cuirassier Division and a Lancer Brigade. To see what actually happened on the battlefield, we will look at it by working North to South. The northernmost force was the French 11 Corps. The 11 Corps, being screened by cavalry, began a frustrating day by becoming engaged tactically almost immediately upon entry on the field. Because of this, the division that was being held in reserve did not have enough room to maneuver to its position on the army's right flank. As the Prussians had deployed so far to the North, the 11 Corps soon became entangled with the Cuirassier Division that was supposed to cross in front of them. Thus the position of the Prussian left flank denied the French the effective use of their real strength in the attack. Eventually, the French Cuirassier Division, using two very effective brigade-size charges, destroyed the first Prussian brigade that was standing in the way of the intitial objective (the rear of the enemy between the Unterhof apple orchard and ridge to the North of Unterhof). The French orders are to blame for this mix up. The Cuirassier Division could not be used effectively against the Prussians because they had no infantry support, and the 11 Corps could not be used because the Cuirassiers were in their way.

In the center, the Prussian Grand Battery, without support, was soon isolated by French forces moving into the gaps in the Prussian line. The Landwehr cavalry supporting it was not strong enough to pose a serious threat to the elite corps that was sent against the artillery. The Grand Battery was almost completely destroyed because of its vulnerable position. In the town of U nterhof one Prussian brigade was faced by the Hesse-Darmstadt division, two Lancer regiments, and an additional 12 lb. battery. The Prussian brigade's positions were chosen well, but itwas soon overwhelmed. The deciding factor for this part of the battlefield was the cavalry in their rear, and the fact that there was no brigade reserve. They were required to hold too much ground with too few troops.

In the south we see one Prussian infantry brigade and one Prussian cavalry brigade faced by a French infantry division, a powerful cavalry brigade and a horse battery. Because of the big gap left between the forest and the town on the Prussian infantry brigade's left flank, it soon became isolated. The Prussian cavalry brigade, outmatched by its French opposite number, did very well holding off the French as long as it did (about three-quarters of an hour). All of the French initial charges were only minor victories, which probably saved the lives of many Prussian infantrymen of the Fourth Brigade.

After thefirst hour of the battle, the Prussians no longer had a continuous front, instead they were fighting four separate battles. The Prussian Corps Commander soon realized this and turned to his messengers to tell the brigade commanders to break off the attack and retreat to Bunzlau. The only problem was that there were no messengers to send; they were all dead. So the last words heard from the Corps commander were "Sauve Qui Peut"; he then raised his bloody saber and charged into the semiskirmisher screen to his front. He was not seen again until the French returned his bullet riddled body the next week.

A couple of French Generals were also casualties during the battle. By some strange fluke, the Division Commander of the Fourth Infantry Division, 11 Corps, was grazed across his left cheek by a stray musket round while he was directing the fire of his artillery on the squares that were formed on the left flank of the Sixth Prussian Brigade. The Cuirassier Division Commander was the second French General to become a casualty. He was wounded while he was leading one of the last charges of the day. The brigade that he was with destroyed the First Prussian Brigade by catching them with a misplaced square. The commander was, as usual, in front of the charge with his saber raised when the Prussian square to his right opened fire. A lucky musket ball entered his back by passing under his arm (unprotected by his Cuirass). The damage is still uncertain, and he is still in the care of the doctor.

Lessons

Lessons to be learned from the actual battle are numerous. First, the Prussian commander was the first one to note that a force faced by three times its number will lose. Second, a battlefield commander with limited information about the forces opposing him should carefully consider his situation. Usually his best option is to engage the enemy with part of his force and wait to commit the rest of his force until he has developed the situation better. Third, never leave gaps in your lines without having some form of reserve.

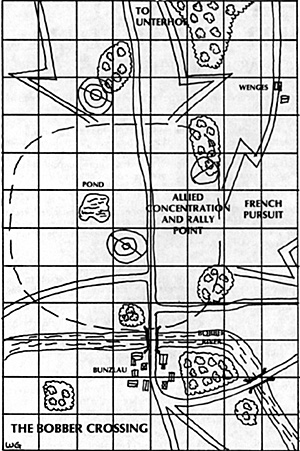

The third phase of this brief look at the Battle for Unterhof is the pursuit of the French. Because the French 11 Corps was unable to effectively engage itself in the battle, it was easily the best choice to lead the pursuit. The French commander decided that the other corps deserved a rest so they did not join in the pursuit until the next morning after they had recovered most of their stragglers. This was a tough decision to make, and the consequences of the French commander's decision will not be known until after the next battle has been resolved. This battle is going to be fought the very next day after this first one, and just about nine miles down the road at the Bobber River crossings.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VII #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com