Repro The recent interest in the era of Napoleon III has been primarily devoted

to what Pat Condray has called the "play-offs": the Franco-Prussian War of 1870

in which Prussia defeated France. While the 1870 conflict is certainly the end of

the era, the Crimean War unquestionably marks the beginning. Indeed, France

became a world power as a result of the Crimean War. But the story of the war is

not just of the rise of France -- it marks a major event in the history of the Russian Empire.

Repro The recent interest in the era of Napoleon III has been primarily devoted

to what Pat Condray has called the "play-offs": the Franco-Prussian War of 1870

in which Prussia defeated France. While the 1870 conflict is certainly the end of

the era, the Crimean War unquestionably marks the beginning. Indeed, France

became a world power as a result of the Crimean War. But the story of the war is

not just of the rise of France -- it marks a major event in the history of the Russian Empire.

The Charge of the Heavy Brigade from a Lithograph by W. Simpson used courtesy of The British Museum, London

Since the days of Peter the Great the Czars have sought to expand the southern boundaries of Russiaat the expense of the Ottoman Empire and its neighbors. indeed, the relatively recent invasion of Afghanistan and the potential threats to Iran are but extensions of the same philosophy. The Crimean War of 1853-1856 was a major effort on behalf of England and France to contain yet another Russian expansion into Turkey. However, what was originally perceived as nothing more than a "colonial expedition" turned into a larger conflict which threatened to involve most of the major countries of Europe.

In 1853 Czar Nicholas I of Russia precipitated a diplomatic incident with Turkey as a pretext for hostilities. Notwithstanding the protests of England and France the Russians occupied the Turkish controlled provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia located on the east coast of the Black Sea. As a result, Turkey declared war on October 5,1853.

The Russians' invasion of Turkey began with an assault on the Turkish lines on the Danube River and a siege of Silistria. Next, the Russian fleet in the Black Sea destroyed a Turkish squadron at Sinope. in addition, the Russians began preparation for an invasion of the Caucasus border region located on the western shore of the Black Sea. A diplomatic resolution of these matters proved impossible, and France and England declared war on Russia in March, 1854.

The reasons for the French and British intervention are certainly complex. In

general, however, England thought the Russian invasion of Turkey as

something of a threat to India. From a more practical standpoint, the English

public became aroused by the Russians' failure to heed the direction of the

government notto invade Turkey. The French motive has often been perceived

as nothing more than the desires of Napoleon III to strengthen his own position

by military victories. For a multitude of reasons France and England - historical

enemies - found themselves as allies against the Russian Empire.

The reasons for the French and British intervention are certainly complex. In

general, however, England thought the Russian invasion of Turkey as

something of a threat to India. From a more practical standpoint, the English

public became aroused by the Russians' failure to heed the direction of the

government notto invade Turkey. The French motive has often been perceived

as nothing more than the desires of Napoleon III to strengthen his own position

by military victories. For a multitude of reasons France and England - historical

enemies - found themselves as allies against the Russian Empire.

Modern warfare concerns itself to a great extent with control of the means of transportation of troops. In 1854 naval superiority was very much a concern because of the proximity of the Russian invasion to the Black Sea. By its control of the Black Sea, the Russians could directly support a land invasion which could conceivably conquer Constantinople.

To thwart the Russian conquest of Turkey both France and England perceived that their objective would be the naval base at Sebastopol on the Crimean peninsula. The destruction of the Russian fleet and the capture of this base would enable the allies to counter the Russian drive into Turkey. As a practical matter, this was the only real "exposed" position since an allied invasion the Baltic to capture St. Petersburg would be extremely difficult due to the strong Russian fortifications there.

To begin the relief of Turkey, the French and English troops sailed to the Black Sea and established themselves at Scutari which is adjacent to Constantinople. From there a large force was sent to Varna on the east coast of the Black Sea. This latter move was originally intended to assist the Turks who were defending the Danube line. But because the Turks successfully held back the Russians, the allied troops were now free to mount an invasion of the Crimea across the Black Sea to take Sebastopol.

The Russians were well aware of the intentions of the allies since almost every move of the English fleet was reported on the front pages of the London Times.

In September, 1854, the allied expeditionary force landed in the Crimea at Eupatoria about 25 miles north of Sebastopol. After several days of "organization", the allied army began its march south. Even at this early stage, it was clear that this was not a drill-ground exercise. There was inadequate supplies and many of the troops were already sick from cholera.

The allied "army" was in reality two separate independent commands. The French were under General St. Arnaud who commanded some 28,000 troops. In addition, the French were supported by 7,000 Turks commanded by Omar Pasha. The English command was given to Lord Raglan, a 65 year old protege of the Duke of Wellington. The English army of 26,000 included the "light brigade" which was the only cavalry available to the allies at this point. The entire allied force moved virtually in line of battle down the Crimean coast with the French and Turks closest to the sea. The English, with their cavalry, supported the left flank. The right flank was under the protection of the allied fleet which sailed alongside of this ponderous formation.

The Russians were well aware of the intentions of the allies since almost every move of the English fleet was reported on the front pages of the London Times. However, the Russians could only muster some 34,000 troops around Sebastopol. This was so because large Russian forces were tied down on the Austrian frontier fearing further intervention by the Austrian army. The local Russian commander in the Crimea, Prince Menshikov, determined that the only defensible position would be at the Alma which lay across the allied line of advance.

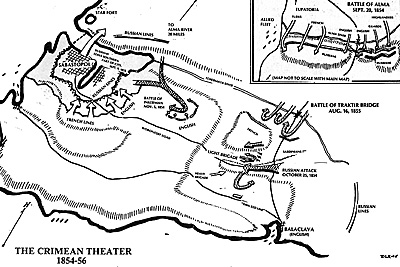

Jumbo Map of Crimean Theater 1854-56 (slow: 161K)

Jumbo Map of Crimean Theater 1854-56 (slow: 161K)

The Alma was certainly an excellent position since the river was commanded by an enormous range of hills affording a clear field of fire. Unfortunately, the Russians left much of their left flank exposed and failed to take adequate measures to erect field fortifications.

On September 20, 1854, the allied armies marching to Sebastopol were facing the Russian positions on the Alma with nowhere to go but forward. The resulting battle illustrated in miniature what would become the typical course of the remainder of the conflict. The English and French commanders never totally agreed on how the battle was to proceed. in general, the French and English both assaulted separate positions of the Russian position in uncoordinated attacks which could have resulted in failure had the allies been facing a more resolute opponent.

The Russians "deployed" primarily in column formation which was disastrous since the column presented an enormous target. The Russian small arms consisted almost exclusively of smoothbore muskets which were not effective at anything over 100 yards. However, the Russians did have excellent support in their artillery which undoubtedly caused the bulk of the allied casualties. The Russians also had a large force of several thousand cavalry which played absolutely no part in the battle.

Many commentators have suggested that the Alma was the most decisive battle of the entire conflict since an allied defeat would surely have terminated the Crimean expedition.

After several repeated assaults, the English were finally successful in carrying the Russian right flank. The French eventually scaled the undefended heights on the Russian left flank. After several hours of bitter fighting the Russians were in full retreat and the allies found themselves in an exhausted condition.

Many commentators have suggested that the Alma was the most decisive battle of the entire conflict since an allied defeat would surely have terminated the Crimean expedition. Certainly, there were several opportunities for the Russians to win the battle primarily by an effective use of their large cavalry force.

After spending some time recuperating on the heights above the Alma River the allies began the "flank march" to Sebastopol. Many writers believe that a prompt pursuit by the allies would have totally destroyed the Russian army. However, the allies were anything but prompt, and instead began a slow advance to their objective.

The allies were again in confusion as how best to proceed. The French commander died shortly after the battle of Alma and his replacement would not take the initiative. As a result, the English were not strong enough to begin a direct assault on Sebastopol, and so the allies agreed to a siege. Writers are certainly unanimous in the view that a prompt allied assault on Sebastopol would have been immediately successful since there were virtually no defenses in the city, and the Russian army was extremely weak.

The resulting battle of Balaclava is best known for the disastrous charge of the light brigade. However, there were two successful British actions during this battle which have been overshadowed by the more famous charge.

The indecision of the allies permitted the Russians to construct earthen fortifications around Sebastopol which were armed by guns pulled from the Russian fleet in the harbor. During most of the following siege the Russian engineering efforts were commanded by Colonel Toldeben who was one of the few bright spots in the command structure of either side. It would be almost a year before the allies could capture the city.

Abandoning their lines back to Eupatoria, the allies established bases in smaller harbors south of Sebastopol. unfortunately, the English chose a very small harbor at Balaclava which was some five miles from their positions. The allies then encircled the southern portion of Sebastopol and began both land and naval bombardments. Actually, the result was in reality not a full siege in that only positions of the town were invested. The Russians had continued access to the city from the north. Furthermore, the Russians had troops across the western portions of the allied lines.

On October 25,1854, the Russians attacked the exposed allied flank and proceeded to the English port at Balaclava. The first line of the allied defense was held by some Turks who were no match for the 25,000 Russians of which about half were cavalry. The resulting battle of Balaclava is best known for the disastrous charge of the light brigade. However, there were two successful British actions during this battle which have been overshadowed by the more famous charge.

The first action was the Russian cavalry attack on the 93rd Highlanders. This little defensive position has come to be known as the "thin red line" because, at the time, it was all that stood between the Russians and the English harbor. The enormous Russian cavalry force never made contact with the Highlanders because they were repulsed by some three volleys of rifle fire. The Russian defeat is understandable because of the new weapons in the hands of the allies. It must be noted that many of the English troops were only recently armed with the Minie rifle which was effective at some 500 yards. In addition to its range, the new rifle had immense muzzle velocity which caused horrible casualties to the thick Russian formations.

Although some Russian cavalry was repulsed an even larger force appeared over a hill to attack the English anew. In their way was the English heavy brigade of some 700 dragoons. Although vastly outnumbered, the heavy brigade charged the Russians who beat a hasty retreat. The defeated Russian cavalry force rode by the English light brigade of cavalry which has been repeatedly criticized for failing to follow up on the victory of their heavier cousins.

During these actions the allied commanders hurried to the scene ana could survey the entire battle from their position on the heights. Because the Russians were removing some captured Turkish cannon Lord Raglan sent a note to the cavalry in the valley below to prevent the capture of the guns. Lord Lucan, the commander of all the English cavalry, directed Lord Cardigan to advance down the valley with his light brigade to "capture the guns". From the perspective of these two men the only guns visible were some Russian artillery located about a mile and a half away; the cavalry could not see the captured Turkish guns on the heights above.

Lord Cardigan directed his troops to the wrong guns and the light brigade

then charged into history. Of the 673 men in the light brigade, 113 were killed,

134 were wounded, and 15 were made prisoner. In addition to the loss of men,

most of the surviving horses had to be shot due to wounds; the light brigade

was crippled as a fighting force. By some quirk of fate, Lord Cardigan, always

in the van of the charge, returned unscathed. Unquestionably, "someone had

blundered".

Lord Cardigan directed his troops to the wrong guns and the light brigade

then charged into history. Of the 673 men in the light brigade, 113 were killed,

134 were wounded, and 15 were made prisoner. In addition to the loss of men,

most of the surviving horses had to be shot due to wounds; the light brigade

was crippled as a fighting force. By some quirk of fate, Lord Cardigan, always

in the van of the charge, returned unscathed. Unquestionably, "someone had

blundered".

Although the light brigade had been destroyed the action had caused the Russians to cease their advance. in addition, the French had participated in the activity by supporting the retreating English forces by a cavalry charge of their own. Nevertheless, the Russians continued to threaten the exposed allied positions.

On November 5 the Russians once again attacked, this time at Inkerman which was on the flank of the English siege lines. This particular battle was fought in heavy fog and resulted in enormous casualties on both sides. Fortunately, the French units managed to support the English and the Russian attack was repulsed.

The allied army was in terrible condition after this battle, especially the English, who had sustained the bulk of the fighting in three pitched battles. Cholera had broken out and thousands of allied troops died. To add to their troubles, a hurricane hit the Crimea and sank most of the supply ships and swept away many of the tents. Then, as if that was not already enough, a blizzard struck. While the French had adequate supplies, the English were in terrible shape which caused great consternation at home.

When spring finally came it was the French who were to take over most of the siege activities due to the English losses. By mid 1855 the allies numbered almost 180,000 men, most of whom were French. With these additional troops the allied continued with the siege, bombarding the city and moving their trenches closer and closer to the Russian lines. Several assaults against Sebastopol were attempted, but were repulsed with great loss to both sides.

On August 16, 1855, the Russians tried one last desperate attack on the right flank of the allied positions near the Traktir Bridge which crossed the Chermaya River. The Russians failed to take the positions and were again repulsed. This combat is noteworthy because it not only involved the French but the Sardinians as well. Sardinia had declared war on Russia in January, 1855 and troops started arriving in force in May. Sardinia had joined the war for purely political reasons and had had "observers" in the Crimea for sometime prior to their actual declaration of war. Indeed, one source reports that two Sardinian officers participated in the charge of the light brigade the year before.

In September, 1855, the allies began yet another major bombardment of

Sebastopol. On September 8, the English and French poured from their trenches and

after a bitter struggle the French were successful in their attack although the English

were again repulsed with heavy losses. Nevertheless, the allies prepared for one

final assault the next day, but during the night, amid exploding magazines, the

Russians withdrew from their positions. However, they only retreated across the

Sebastopol harbor and were firmly entrenched on the north side of the city. As a

practical matter, the allies had accomplished nothing. Although the Russians could

not use the harbor, neither could the allies. Thousands of lives had gained only a few

yards -- shades of World War I.

In September, 1855, the allies began yet another major bombardment of

Sebastopol. On September 8, the English and French poured from their trenches and

after a bitter struggle the French were successful in their attack although the English

were again repulsed with heavy losses. Nevertheless, the allies prepared for one

final assault the next day, but during the night, amid exploding magazines, the

Russians withdrew from their positions. However, they only retreated across the

Sebastopol harbor and were firmly entrenched on the north side of the city. As a

practical matter, the allies had accomplished nothing. Although the Russians could

not use the harbor, neither could the allies. Thousands of lives had gained only a few

yards -- shades of World War I.

Later, the allied Pacific fleet heard that the Russians had established a base in Alaska, sailed away to it, only to find the report false and the war over.

The "capture" of Sebastopol was by no means the only allied activity in 1854 and 1855. Even before the initial invasion of the Crimea, the allies planned to obstruct Russian naval activity in the Baltic and so the French and English dispatched a fleet there in 1854. While there were several bombardments of various Russian forts in the area, the primary activity consisted of a land and sea assault on the fortress located at Bomarsund. Here, some 6,000 French and English troops captured the fort and forced the surrender of some 2,000 troops. In 1855 the allied fleet returned to the Baltic area and bombarded the forts protecting the entrance to Helsinki which was under Russian control. This accomplished very little and the remainder of the war in the Baltic was spent in blockade duties.

In the Pacific, the English and French fleets attacked several Russian bases, mostly without success. One attack began with the English commander committing suicide in his cabin, after which the late general's troops were repulsed with heavy loss. Later, the allied Pacific fleet heard that the Russians had established a base in Alaska, sailed away to it, only to find the report false and the war over,

As noted earlier, the Russians had invaded Turkish territory on both sides of the Black Sea. The first invasion resulted in the unsuccessful siege of Silistra. Eventually, the Russians withdrew from the Danube area due to their failure to take Silistra as well as being under intense political pressure from Austria.

While the Russians failed in their invasion in the Danube area they were far more successful in Asia Minor. Here, the Russians advanced to Armenia and besieged the city of Kars. Kars, in a way, was like Sebastopol in reverse. The Turkish garrison was effectively under the control of Colonel Williams, of the English army. From September, 1854 to November, 1855, Williams' heroic efforts prevented the capture of Kars. However, the allies refused to send aid even after the fall of Sebastopol, and Williams was eventually forced to surrender the garrison. Fortunately, the war did not last long enough for the Russians to exploit their success.

During the activity around Sebastopol the allies correctly observed that it would be necessary to restrict supplies to the Russian field army in the Crimea. To this end, the French and English conducted several amphibious assaults on various Russian bases in the Black Sea. The allies occupied Eupatoria with several thousand Turkish troops. This position was unsuccessfully attacked by the Russians on February 17,1855. In May, 1855 the allies landed some 15,000 troops in Kertch to block the Russian supply lines through the Sea of Azov. After the capture of this place, the allied fleet destroyed much Russian shipping in the Sea of Azov.

In October, 1855, some 10,000 allied troops attacked the ports on the Bug and Dneiper rivers located in the north of the Black Sea. This force was led by General Bazaine who was later to command the garrison of Metz during the Franco-Prussian War. The English contributed some two battalions of marines as well as the 17th, 20th, 21st, 57th and 63rd regiments. The expedition was a success and the Russian forts around Kinburn eventually surrendered.

Although the allies had been successful in many of their activities in the Black Sea, the winter of 1855-1856 once again pitted the allied army in the Crimea against the elements. But this time it was the French troops who suffered the most and they had to seek assistance from the English. The activity around Sebastopol came to a cautious halt.

By late 1855, the Russians were thoroughly exhausted and intense diplomatic activity was underway to bring an end to the war. Nevertheless, even though Sebastopol had fallen, the allies were seriously considering further military activity against the Russians. Napoleon III even thought of coming to the Crimea himself to command a field army for the invasion of southern Russia. With peace "in the air", however, the French perceived that there would be no benefit to further military activity. The English, on the other hand, were certainly not of this mind. While the English were slow to get started, their military forces were becoming stronger.

Indeed, a number of mercenaries, including Americans, were enlisted to fight for the English. However, Austria was threatening to intervene on behalf of the allies if the Russians did not bring the war to a conclusion. Faced with the threat of yet another adversary, the Russians agreed to an armistice in February, 1856. In March, 1856 a treaty was signed which brought the war to a conclusion.

By the terms of the peace treaty, the territory seized by the Russians was returned to the Turks. Further, the Russians were prohibited from having any military forces in the Black Sea area. It was obvious that France was the primary factor which kept the Russians to the terms of the treaty illustrated by the fact that Sebastopol was garrisoned anew only after the French reverses in 1870. In 1877 the Russians and Turks were at it again and, at this point, the Russians were successful in taking much of the territory which they failed to capture from the Turks in the Crimean conflict.

The Crimean War, in retrospect, was more than just another quest for territories. New methods of destruction made their first appearance. When the conflict began, the tools of war were virtually unchanged from those present at Waterloo some 40 years earlier. Yet, at the end of the conflict, the technology of the era was more akin to that of the First World War some 50 years later. Indeed, Frank Chadwick has characterized the Crimean conflict as the "dawn of modern warfare". Chadwick is certainly correct in this observation. For example, the French employed "floating batteries" which were actually the first ironclad warships. While these vessels had masts they were also steam powered. Three of these ships were used off Kinburn.

When the conflict began, the tools of war were virtually unchanged from those present at Waterloo some 40 years earlier. Yet, at the end of the conflict, the technology of the era was more akin to that of the First World War some 50 years later.

On land, other new inventions made their appearance. In the Crimea, the British built a small railway from their lines to their port at Balaclava. The electric telegraph was also used and stretched from the lines around Sebastopol to England and France. This proved to be a mixed blessing because the generals at home could conduct the war with no idea of what conditions were really like on the field. Things got so bad that the French commander was forced to cut the telegraph line.

The most deadly form of warfare by far took place during the various siege operations. As the allies advanced on Sebastopol the Russians threw up earthen defenses on the land approaches, strong enough to hold the allies for almost a year. In front of the trenches were various rifle pits and man traps. The Russians employed wooden planks studded with six inch nails in front of their works. They also dug holes and covered them with a little straw and dirt. These obstacles proved to be very effective against a storming party.

To overcome them, the allies used bags of wool and small bundles of straw which the troops threw on top of the obstacles. Not to be outdone, the Russians began using various types of land mines. The first type was buried just below the earth and exploded when a man walked on it. Another type was also buried, but under several large stones. These mines were detonated electrically through wires running back to the Russian lines. When an attacking party neared one of the mines, they were exploded, sending a shower of rocks in all directions. Electric mines called "torpedoes" were also used in the defense of naval ports in the Baltic.

Artillery weapons became larger and some were rifled. This dramatically increased the range of the batteries. Similarly, the allies began the war with rif led small arms in many of their units. In the English army, all of the troops, except those in the Fourth Division, had Minie rifles at Alma. In 1855 the army began receiving the new Enfield rifle which was superior to the older Minie. in addition, the English employed several sizes of Congreve rockets which had a range of up to 1,000 yards. Occasionally, these rockets were mounted on small boats for a seaward attack.

The Crimean War is also noted for other "firsts". We are all familiar with the efforts of Florence Nightingale who dramatically increased the level of medical care. The first war correspondent, W.H. Russell, sent back reports to the London Times that in many instances, afforded the Russians better information than their own spies. The first war photographer, Roger Fenton, has provided us with pictures of the participants in the conflict.

Crimea: Suggested Reading and Gamer Resources

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VII #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com