It has been my frustrating experience that even the best miniatures rules for the Seven Years War in Central Europe transplant very poorly to the North American theatre (Americans south of us call it the French and Indian Wars; we Canadians, however, do NOT call it the English and Indian Wars). This is a pity, for some of the most colorful uniforms and characters in the war appeared on THIS side of the Atlantic and some of the most important battles in the hemisphere took place at Fort Ticonderoga, Fort Duquesne, and Quebec. Why do rules, which work perfectly well for battles involving Frederick the Great or the Duke of Cumberland, prove so disastrous and boring for Wolfe and Montcalm? I suspect it is the woods.

It has been my frustrating experience that even the best miniatures rules for the Seven Years War in Central Europe transplant very poorly to the North American theatre (Americans south of us call it the French and Indian Wars; we Canadians, however, do NOT call it the English and Indian Wars). This is a pity, for some of the most colorful uniforms and characters in the war appeared on THIS side of the Atlantic and some of the most important battles in the hemisphere took place at Fort Ticonderoga, Fort Duquesne, and Quebec. Why do rules, which work perfectly well for battles involving Frederick the Great or the Duke of Cumberland, prove so disastrous and boring for Wolfe and Montcalm? I suspect it is the woods.

To start with, I don't know of a miniatures gamer who has enough tree models to cover his whole table. So what happens is we cover as much of the table as possible and leave the rest clear. This is not really a North American battle we're reproducing but rather a European battle without cavalry. No wonder we find it slow and boring.

European woods are rather small and annoying. A tiny copse of trees was easier to skip around than cut through. Most rules reflect this by penalizing movement through woods. This makes sense because such a small thicket would allow sun and rain to penetrate and nourish even the smallest seedlings. The virgin North American forests were totally different, as anyone who has tramped around the wilderness in Vermont, Ontario or Quebec can tell you. The sun only penetrates the edges of these dense woods. Once beyond this fringe of undergrowth, the woodswanderer is confronted with only the large trunks of mature trees, with huge spaces between. What is more, the forest floor is firm and often carpeted with pine needles or leaves. In fact, one can move much faster through this terrain than over a plowed field or through a sea of rye.

The solution - penalize movement only when moving through the underbrush on the fringe of the forest - or even better; don't penalize movement through woods at all.

More important than movement, however, is the fact that the woods give the North American conflicts their own unique flavour. And that flavour is one of aimless, hopeless, lost, wandering - an aspect totally absent from the battles in Europe. You have to really try to get lost in 300 square yards of woods. The task becomes much easier in 1,000,000 square miles of forest between here and Montreal. To capture this flavour we need a whole new approach to our games.

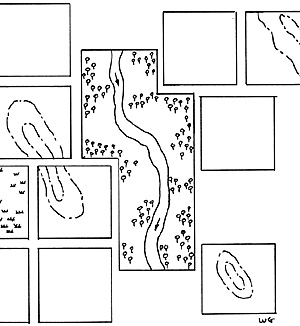

Our group sets out the terrain up to 12 inches on either side of the line of advance (usually a forest path or a river). An umpire keeps a map of what is outside this 24" strip (see illustration). Now, either your whole army advances on a 24" wide, frontal assault (it happened - with predictable results) or you venture into the deep, dark woods. Once into the woods the umpire sets out the terrain on a 24" square piece of board and sends the commander of this detachment off, away from the table, to maneuver his troops. To increase the confusion the player sits facing his own troops and moves them towards himself. This works great for the first 2 or3 times it is used.

By the 4th or 5th time the game is played the players get accustomed to the above system and stop taking wrong turns. So, we introduced another twist. When the troops reach the end of their square and prepare to move onto the next terrain piece, the umpire rolls a die. Europeans, regulars, militia and anyone else unfamiliar with frontier life have a one-third chance of taking a wrong turn. if they do, the umpire rolls again; 1-3 they leave the terrain square one side to their left (i.e., if they were supposed to go off the north edge, they now go off the west edge); 4-6 they leave one side to the right (east edge). Rangers, Frontiersmen, Indians, Coeur du Bois and anyone else at home in the woods only have a one-sixth chance of taking a wrong turn. The umpire never states whether the troops took a wrong turn or not. He just keeps directing the troops to their new terrain squares.

If the troops reach the map's edge they are considered to have bumped into some impassable terrain (a cliff, lake or dense woods, etc.) or to have realized that they were too far off track. They turn around and search for a new route off their present terrain square.

Swamp squares are special. Troops that stumble into swamps are stuck for a die roll's worth of turns. They then backtrack onto the square they occupied previously. Or, in some games we have them simply disappear altogether (only to re-appear in Boston three months later mumbling something about moose-juice and walnuts, we're told). Indians, Woodsmen, etc. are not that stupid. As soon as they see woods, instead of jumping in, they head straight back to the Commander-inChief, who sent them there (he's usually on still on the main line of advance). They report to him, question his ability to command, insult his mother and then head back into the woods.

Since everything outside of the main 24" strip is considered to be forest we don't even use model trees, except on the main table. The terrain square are clear of trees, but sighting, musket ranges, and cover are limited as per the usual woods rules.

Now, this is wilderness warfare as it was meant to be -- swift, unsure, exciting. Regulars and Grenadiers sticking to the known paths and clearings. Indians and Woodsmen streaking through the trees, trying to gain a flank or lure some militia into the woods- -never to be seen again - -or to stumble out in an even better position than when they went in!!!

Great stuff - Montcalm would be proud.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VII #5

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com