Successful tabletop games require the happy confluence of several factors: figures, rules, the table itself, and a good scenario. Designing a good scenario seems not to be as easy as it should. Onetime I spent many long hours carefully preparing my troops and terrain for a re-fight of Waterloo. Combining resources with friends, I was able to represent each battalion. Full of anticipation, I made victory conditions which, for the Prussians, centered around the capture of Placenoit and cutting the French line of communications. More time was spent exactly modelling the terrain. An HMGS announcement duly noted that a re-fight of Waterloo was intended. It seemed nothing could go wrong, yet the event was both a miserable reconstruction and a boring game.

I thought the victory conditions were so obvious that I failed to adequately brief the Prussian commander. He, in turn, knew little about the historical performance of the Prussians and completely ignored Placenoit and the French LOC during his maneuvers. His wanderings along the French flank entirely disrupted what should have been a fine gaming experience.

Similarly, I have participated in other people's historical re-fights that have turned out to be less than wonderful. One knowledgeable fellow (I won't mention your name, Bob Coggins), enticed me to his recreation of Maloyaroslavetz, a pivotal battle that took place during Napoleon's retreat from Moscow. He had done careful research about the bridges and fords spanning a small river that ran through the battlefield's center. The problem was that by the time the players commanding the French had crossed the river, it was getting on towards midnight and neither side had come to grips!

These experiences highlight two problems that plague many scenarios: fuzzy explanation of victory conditions and overly ambitious expectations of how much can get done during the course of a gaming evening.

"For some reason the majority of tabletop battles seem to be encounter battles... historically only a minority of battles were meeting engagements..."

Both these problems can be easily avoided. Victory conditions can be simple - "this is the critical terrain feature, whomever holds it at the end wins" - or complex - "you must reach this road junction in four hours of historical time, preserve your own line of communications, and suffer less than 20% losses" - but they should be carefully defined before the game begins. Even when one wants to preserve the fog of war and not brief the gamers on all the factors that determine victory, the scenario designer had better have these factors written down. otherwise he faces the uncomfortable scrutiny of his guests as they glare at him and ask, "well, who won?".

A simple rule of thumb can be used to ensure that the attacking side has enough time to have a reasonable chance at victory. Measure the distance from the attacker's start line to his objective. Divide this by the distance covered in an average, unopposed move. if the attacker can barely get there by a simple route march, let alone during a contested advance, you had better change something.

It is remarkable how often this simple rule is ignored. At a convention I was given command of a truly impressive array of thousands of fine 15mm figures. The rules were explained and objectives defined. Basically I needed to cross the tabletop, pass over a river, and attack the enemy's flank. Full of zeal I began my march. My only opposition was a regiment of hussars so my two corps set out at full bore. Reaching the river I learned it was unfordable. I headed for the only bridge. The hussars got there first, burned the bridge, and that was that. All of this took some three hours of playing time (other gamers were engaged frontally while I made this useless flank march). To let me get a feel for the rules system, on the last turn of the game the river mysteriously dried up and I was able to pitch into the enemy's flank. But the experience wasn't much fun.

Preliminary Calculations

So the scenario designer can do some preliminary calculations: how far does a unit have to travel (say a 5 turn march), how many times is it likely to be engaged (say once to pierce the first line and once to beat the reserves), how much time does deployment and battle usually take (say the approach march complete with formation changes takes twice as long as a route march while the two battles require a turn each). Does this give the attacker a reasonable chance? If not then either his start line should be moved forward, his objective brought closer, or the defender's strength reduced.

For some reason the majority of tabletop battles seem to be encounter battles. Each player starts on his side of the table and marches towards the enemy. This is a mistake on two accounts: historically only a minority of battles were meeting engagements; and an awful lot of valuable gamer's time can be taken up in preliminary maneuver that is better handled on a map before anyone even arrives at the tabletop.

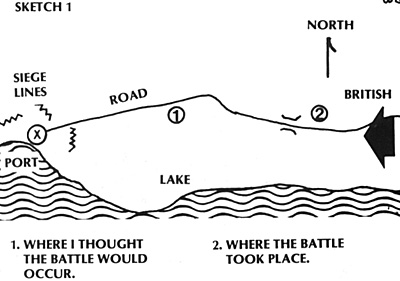

A third major problem in scenario design I will call inflexibility; the inability to predict how gamers will react to the situation the scenario places them in. At a recent HMGS affair, I hosted a War of 1812 scenario (Sketch 1). Basically, the British entered on the road and could also send troops by ship to the port. Their objective was to bring an overland resupply convoy to the port which was under siege by the Americans. Other American forces lay hidden in the wilderness. I applied the above mentioned rule of thumbto determine if the British had a realisticchance in the three hours I allocated for the game.

A third major problem in scenario design I will call inflexibility; the inability to predict how gamers will react to the situation the scenario places them in. At a recent HMGS affair, I hosted a War of 1812 scenario (Sketch 1). Basically, the British entered on the road and could also send troops by ship to the port. Their objective was to bring an overland resupply convoy to the port which was under siege by the Americans. Other American forces lay hidden in the wilderness. I applied the above mentioned rule of thumbto determine if the British had a realisticchance in the three hours I allocated for the game.

"Keep the design simple, let the players add the complexity through their tactical invention and human interaction."

The crucial mistake I made was in anticipating what the British commander would do. I believed that the solution to his tactical problem was to land enough forces at the port so they could march toward the main body. Thus, the two separate columns would join somewhere at the table's midpoint. The Americans would (so I figured) try to prevent this linkup and the result would be a rousing two-front action at a place on the table (the center) where there was ample room for maneuver.

WRONG!

The British player did send forces by sea. But once they got there the commander timidly holed up and waited for relief. Consequently, the other British player now had to march almost twice as far to initiate a battle as I had anticipated. There would not be enough time. Fortunately, the aggressive American commander attacked instead of waiting behind a comfortable defensive position and a good time was had by all. But, it had been a near run thing!

I cannot provide a solution to this inflexibility problem. All I can offer is a warning for the scenario designer to be alert and to try to accommodate his players' tactical imaginations (or lack thereof) sometimes to the extent of changing the victory conditions after the battle has started (but don't tell the players you've done this!).

TWO SCENARIOS THAT WORKED

A second scenario I ran at HMGS proved very successful in both concept and execution. It also shows that simple is quite often best. Keep the design simple, let the players add the complexity through their tactical invention and human interaction. The concept came from an actual Civil War battle between Early and the pursuing Yankees in 1864, following Early's retreat from Washington. I have the privilege to live in the Shenandoah Valley and thus making the mini-campaign map was easy. I changed the period to an American Revolutionary battle (it could just as easily have been an Ancients or Napoleonic) while retaining the terrain and overall objectives.

A second scenario I ran at HMGS proved very successful in both concept and execution. It also shows that simple is quite often best. Keep the design simple, let the players add the complexity through their tactical invention and human interaction. The concept came from an actual Civil War battle between Early and the pursuing Yankees in 1864, following Early's retreat from Washington. I have the privilege to live in the Shenandoah Valley and thus making the mini-campaign map was easy. I changed the period to an American Revolutionary battle (it could just as easily have been an Ancients or Napoleonic) while retaining the terrain and overall objectives.

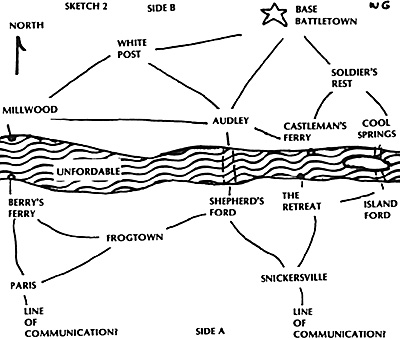

The two sides started on opposite sides of the river (Sketch 2). It can only be crossed at the fords and the two ferries. Crossing at the fords takes two turns, the ferry only one. Only one brigade may cross per turn. A outnumbers B at least 4:3. This information both sides knew. Side A secretly designates a LOC along either the Berryville or Millwood Pike. He must protect this while seizing Side B's base. B must cover the escape of his trains and try to hold his base. Failing to hold his base he must evacuate his trains and burn the base. However, only half his force is available at the start; the remainder appear at his base after one hour of real time.

I kept in my possession knowledge of how to resolve attempts at crossing the river. Each brigade would roll a six-sided die. The defender would add two, if either side had artillery support it would add one. Acting as the judge, I would make the die rolls an announce results (e.g., the attacker tries to force Castleman's Ferry at 7:30 A.M., he comes in brigade force and is met by an equal force on the far shore. He succeeds in gaining a bridgehead, each side loses 100 men, B retreats to Berryville and A controls the crossing).

I think it is important to keep the mechanics of how the judge resolves the action secret to prevent hindrance by rules lawyers. However, the gamer must be given enough information to make rational decisions.

"... it is important to keep the mechanics of how the judge resolves the action secret to prevent hindrance by rules lawyers."

In the event, this scenario proved entertaining, full of probes, bluffs, and finally a ding-dong (ED NOTE: This is a superlative expletive, not a negative one in Jim Arnold's lexicon) battle at Audley complete with both sides marching reinforcements to the sounds of the guns. The planning and map moving consumed about an hour, the tabletop encounter 2.5 hours. So, in a very manageable 3.5 hours a tabletop battle complete with a campaign context was staged.

The river crossing scenario worked at an HMGS convention when players didn't know the rules and I didn't know the players. The following scenario may work best when the scenario designer acts as judge for friends who have a knowledge of the period.

ROUT!

I designed this scenario as both a gaming challenge, the opening partof a campaign (using those wonderful Kriegspiel re-print maps), and to test a theory. One often reads how a general failed to pursue vigorously enough to convert an ordinary victory tosomething more. By putting the players in such a situation I hoped to learn why this was so.

I designed this scenario as both a gaming challenge, the opening partof a campaign (using those wonderful Kriegspiel re-print maps), and to test a theory. One often reads how a general failed to pursue vigorously enough to convert an ordinary victory tosomething more. By putting the players in such a situation I hoped to learn why this was so.

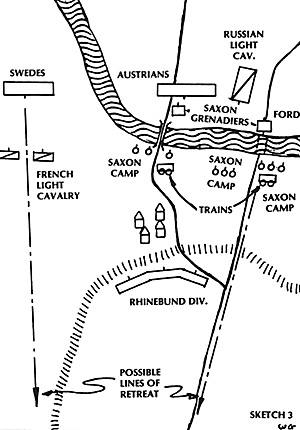

The scenario opens in late morning. A large battle has been fought off the map to the east. The French and French-Allies suffered a defeat and are retreating from the field. A pursuing Swedish divisional commander meets with an Austrian advance guard commander on a hill overlooking the field. Rather than brief them on the scenario, I conducted the two players to the edge of the table and let the setup speak for itself. What they saw is shown on Sketch 3.

I added a few details such as "smoke is rising from numerous campfires within the Saxon lines" and "a questing division of Russian light cavalry is rapidly advancing near where you stand". Mostly however, I let them look and plan, telling them that as they met, time was passing. At appropriate moments I moved the trains slowly towards the west. in addition, liberal doses of alcoholic beverages were provided to recreate the general command confusion of those hard drinking times.

What the players could not know was the status of the Saxons. They knew they were pursuing defeated troops, but could not know the extent of the Saxon demoralization. They also did not know how many French troops might be concealed by the folds of the ground. This, I think, accurately recreates some of the real factors that constrain a general from ordering an all-out pursuit.

In fact, of all the Saxons, only the grenadier brigade had any fight left in it. As soon as the bulk of the Saxons were fired on, saw enemy troops approaching, or saw friendly routing troops, they would automatically rout themselves. In addition, a Confederation of the Rhine Division lay concealed along the western slopes. They had orders to cover the Saxon retreat.

Unbeknownst to the Austrian, the Swede had cover orders to minimize losses. To reflect the difficulty of allied cooperation, neither Swede nor Austrian could control the Russian since they were all equally ranking division commanders. They could suggest a course of action to the Russian, in which case I made a judge's roll (40% likely the Russian would obey). Finally, to add spice, I tossed in a British rocket battery, a small squadron of light dragoons, and that inspired busybody himself, Colonel Sir Robert Wilson.

The whole brew blended into an exciting mix in which the players tried to execute a conventional deep flanking attack. Against an intact foe, this would have worked well. Against the skitterish Saxons it proved less than a perfect choice. The bulk of the Saxons, covered by the heroic sacrifice of their grenadiers, fled from the rapidly closing jaws of the Allied envelopment and two-thirds of their baggage and trains escaped.

The scenario showed us that arm chair generals with perfect hindsight might perform no better than historical generals even when placed in a position full of great opportunity.

Much has been written and said about recreating the fog of war. A good scenario will accomplish this. However, the designer must avoid imposing so much fog upon the players (even if this is realistic) that they become totally confused and frustrated. Remember, fun as well as realism is a goal of scenario design.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VII #5

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com