I suppose many people who play Napoleonic wargames secretly want to be Napoleon, and part of the attraction of the hobby lies in this sort of Walter Mitty fantasy. When one 'takes command' of an army of lead soldiers (or of cardboard counters, come to that) one is imagining oneself 'in the shoes of' a Napoleonic general. We often hear wargamers discussing their'generalship'as if they haveactually been generals-and on occasion we even encounter boasts that such-and-such a spotty-faced youth believes he is an even better general than the Emperor himself!

The trick, of course, is that most wargames make an abstraction of generalship and look at only one particular aspect of it, i.e., the movement and tactical deployment of troops in battle. Therefore when a wargamer says he has shown 'good generalship' he really means that he has chosen to move his units to the right place at the right time and in the right formation. Those are the decisions that he has had to make for the game, and no others.

In real life, however, there is a lot more to generalship than just this 'tactical decision making'. The general must win at least the obedience of his subordinates and the confidence of his superiors. He must select the right men for each job, and not be afraid to sack incompetents. He must be skilled in the strategic arts of ingelligence collecting, logistics, diplomacy and concentrating the army on the battlefield. Once in battle he will need physical stamina and courage to move under fire and transmit his orders to everyone who needs to receive them. He must also keep alert to what his subordinates are trying to tell him, just as he must keep them informed of his own intentions. Indeed, the purely tactical decision is probably the easiest part of all: translating the decision into practice is the really difficult part.

In order to incorporate some of this into a wargame, we should distinguish two different approaches, which for convenience I will here call the 'Functional'and the 'Theatrical'. They come in increasing levels of difficulty, so I leave it up to the reader to decide which of them he may wish to attempt.

Normal wargames can be called 'Functional' role plays in the sense that the player has to perform the general's function of selecting his tactics and movements. As we have seen, however, a Napoleonic general in battle actually had other functions as well as these, so a more elaborate game could be designed to represent some of them. For example each of your (non-played) subordinates could be allocated a set of characteristics which make him suitable for certain tasks but not for others. The player would have to choose the right man for each job, and suffer a penalty if he got it wrong. Hence if a 'Napoleon' made Soult his chief of staff at Waterloo, and Ney his left wing commander, he could expect to suffer from hostility and misunderstandings between the two men, poor staff work from Soult and recklessly ill-coordinated attacks from Ney (just like in the real thing, in fact!).

Personal feuds between leading Napoleonic commanders were very common, and it would not be difficult to reflect this in a list of vendettas for each subordinate, with tactical cooperation disallowed between any pair who 'didn't get on'. Such a system could also extend to factions of 'friends' who would withdraw their cooperation from a player who sacked any one of them (unless he gave compensation in the form of plum jobs for the survivors). Thus each battlefield task could be graded according to its honour status and the degree to which it involved collaborating with others. The player would have to negotiate his way through the political complexities of making the right appointments before any tactics - whether good or bad - could work at all.

By the same token the rules for gathering and transmitting information on the battlefield might be refined to give a more interesting representation of this function than is usual in wargames. This is not just a matter of insisting on realistically slow movement rates for couriers (and realistically inaccurate estimates of enemy numbers), but also of legibility and relevance in the message sent. Could you really write a good operations order if sitting on a horse in the rain, with limited time? I am not suggesting that you should put it to the test literally, but as an easy substitute how about writing a message within 30 seconds using the hand you don't normally write with? Then check over the results at leisure to see if they really say what you wanted them to.

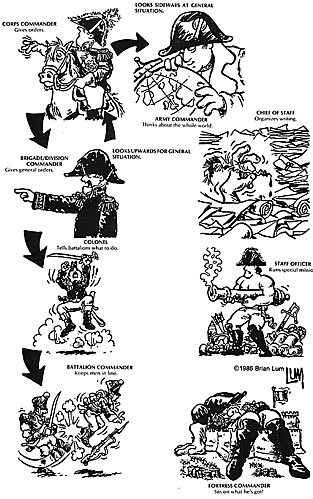

The functions of generalship did, of course, vary greatly according to level of command, and post. Here are a few examples from a French Army about 1806:,

Major or Battalion Commander: Little role in tactical decision making, but a difficult task in raising morale and keeping the men in line.

Colonel or Regimental Commander: Responsible for many of the tactical decisions but 'looking downwards' to his battalions rather than upwards to the wider battle. just obeys higher orders for the latter.

Brigade or Division Commander: Little concerned with minor tactics, but far more with grand tactics and even strategy. 'Looking upwards' to interpret the orders of higher authorities. Responsible for quite a wide area of the battlefield and concerned to keep a reserve, keep liaison on the flanks, &c..

Corps Commander: Almost an independent actor within the commander in chief's grand drama, with self-contained 'army in miniature' under command. The Corps Commander would be responsible for a very wide piece of terrain, and would often stay well behind the firing line. He would adopt a highly 'managerial' style of command, rather than one based on personal leadership.

Army Commander: Either Napoleon himself, with all the cares of the Empire on his shoulders, or a senior marshal worried about what Napoleon will think of him. Complete independence of action within the theatre of war, usually accompanied by a completely 'managerial' style of command. (Note that Napoleon's correspondence for a single day on campaign makes a file a foot thick!)

Corps or Army Chief of Staff: A pure administrator, whose only interest in minor tactics is to provide an adequate ammunition supply. Must be good at calculating movement rates and logistics, in order to make his commander's plans come to life; but exercises personal leadership only over a few office clerks.

Corps or Army Staff Officer: High ranking staff officers were often used to ride out and collect information or to grip a dangerous situation at a distant part of the line. An interesting wargame could be designed around their exciting and varied experiences, but it would be more of an 'individual skirmish' game than a conventional battle game. The difficulty would be for the game designer to lay on several quite different problems in quick succession.

Fortress Commander: The art of commanding a fortress under siege is different from the art of command in mobile warfare. it demands a rigid parsimony of resources and a long-term determination to hold out, even though common sense might dictate the need to reach an agreement with the enemy. Concerned mostly with morale and logistics rather than the technicalities of engineering, but forced by personal proximity to his troops to 'lead from the front'.

For each of these different types of Napoleonic generalship there could be a different type of functional role play game. The staff officer would be given problems of paper flow and the analysis of information, while the battalion commander would be presented with an individual skirmish game in which he had to rally shaky troops and persuade them to shout or sing--in unison! The potential variety is enormous, although not all of the possible games might have much point of contact with conventional wargames.

Beyond the 'Functional' game, furthermore, there lies the more ambitious 'Theatrical' type of role play. The rationale for this game is that if you are trying to play the role of a person in the past it is not enough simply to perform his functions. You must also try to adopt his way of looking at things; his instinctive attitudes, even his personality. Hence you are led logically into the sort of role play which actors use in the theatre - a dramatic portrayal of a personality which is not their own.

First Step

The first step is to decide just what type of personality you want to role play. This can be done either by 'rolling up' a character (D&D style) or it can be done by historical study - as actors do it. At first it is best to try something very simple and straightforward, e.g., you might choose to portray a caricature of Marshal Ney with only one idea in his head: attack! Even though you, as the modern player, might judge that immediate attack would be disastrous, the demands of the role play will be such that you are forced to launch them. Who knows, you might be lucky enough to face an opponent who is playing a timid and sickly Austrian...

The fun of such a game would not, in any case, lie in finding tactical winners or losers, but simply finding which player acted out his part most accurately. Thus a 'Marshal Ney' who spent most of the game bawling in frustration after his squadrons had been broken on the English squares would have turned in a better performance than one who cut the English line by careful utilization of the three arms. Note also that because this wargame would not be competitive in the normal sense of the term, the two sides could be trusted to reach an amicable assessment of each other's performance. After a couple of efforts they could then start to help each other to improve, until eventually they could graduate to the really difficult roles of more complex personalities than Ney.

In one large experiment at a Wargame Developments conference there were four teams of four players each, with each player having a particular type of personality and a particular tactical policy to argue for. Each team also had an umpire to award points on how well the players portrayed the personality they were supposed to portray, thereby making - it was hoped - a 'realistic' portrayal of a large council of war. Unfortunately it didn't really work very well because I failed to explain it all properly to the participants, but as a game structure it might have worked - and a number of subsequent efforts by others have helped to refine it.

Criticisms

Two particular criticisms tend to be levelled against this type of 'Theatrical' role play, but ultimately I do not believe that either of them stands up to examination. The first is that the exercise is futile since 'a twentieth century civilian cannot possibly hope to think like a nineteenth century soldier'. This is another way of restating the cynical view that history itself is worthless, since it describes 'What did not happen, written by someone who was not there'. Maybe in strict philosophical terms this is fair enough, but it it scarcely a line of reasoning which any practising historian - or amateur historian - can afford to follow very far. Surely the whole business of thinking about history is precisely a matter of 'thinking oneself into the shoes' of people in the past, even if it cannot be done with perfect accuracy. By the same token, in fact, the serious student of the past even has a duty to think himself into his characters' personalities in this way. Merely assessing the chances of victory and defeat from the external movements of battalions and guns is really only a rather minor part of the historical process.

The second criticism levelled against the 'Theatrical' role play is that wargamers are not usually actors, and are therefore technically unfitted to act out their roles. There is a clear danger that even the most seriously intended role play can degenerate into merely a game of 'silly hats'. The risk becomes almost a certainty if - as most wargamers tend to do - the participants regard their hobby games as 'just a good laugh'.

Even with the most serious will in the world, according to this critique, the wargamers will lack the preparation and experience which are needed to make a good theatrical performance. They will plunge in over-hastily and make a thespian mess of the whole thing. Proper acting, by contract, demands far more homework and self restraint than the untutored amateur is prepared to give it.

Once again, this critique does indeed have a certain logic behind it; but in my experience its strength lies in the fact that no wargamers have really given the theatrical role play a fair trial. Maybe some of the outdoor reenactment groups have done so, but we indoors wargamers have been strangely slow to try our hand. If we were seriously to tackle the problem, however, I can see no logical reason why we should not overcome all objections. We could do our homework on this, just as we do it on research for uniforms and tactics. We could gather the experience and practical skills of acting, just as we do for playing and winning our tabletop battles. We could make each game into a star performance designed to deepen our understanding of the historical characters!

In any case, even if our dramatic experiment really did not manage to rise above the level of 'silly hattism', it could still turn out to be deuced good fun, and even historically respectable too. I mean that the historian is not inevitably compelled to observe a hushed and respectful awe when he confronts a figure from the past - he has the option of satire open to him as well. Napoleon himself was certainly the object of much cruel satire at the time of his reign, and there is no particular reason why today's wargamer should not also subject him to it. Many of us find 18th century attitudes very strange indeed to our modern way of thinking, and it is therefore easier for us to poke fun at them by exaggerated histrionics than to rehearse them with a straight face.

Having chosen one's subject and decided between the serious and the satirical approaches, one can start to rehearse for the part. How would your man react to good news or bad news? How would he set about analysing a tactical situation (if he bothered to analyse it at all, that is)? How would he talk to people in his entourage? How would he sit down and stand up? We have plenty of good information about these things for many of the leading commanders of the Napoleonic Wars, and we can easily make up the answers to questions for which documentation is unavailable. All it needs is you - the wargamer-cum-actor - to sit down and try to find the answers that satisfy you for the particular personality you have chosen to portray.

Finally you get into the performance itself. You might wish to put on your performance in the course of a conventional wargame, but it would probably be more suitable for you to structure the event specifically around the role play. Give your performance to an impartial umpire or to your assembled wargame club. Do it as a one-sided game or with two sides, each in separate rooms, each 'playing to' the same umpire team. Do it as group therapy for a whole staff tackling a particular problem. Do it in a proper 'theatre workshop' environment or on video. Do it in whatever style seems best to you - but the important thing is to DO IT! Theatrical role playing is the logical next step for many types of historical wargame, and it would be a pity if wargamers shied away from it out of false modesty, or fear of getting it wrong or looking silly. Have the courage to follow the logic of your hobby - not just its conventional morality!

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VII #3

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1986 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com