"The War of 1812 is an extremely interesting variant of the Napoleonic

Wars, well worth the effor tto recreate on the tabletop", said noted gamer Chris

Johnson. And he is right!

"The War of 1812 is an extremely interesting variant of the Napoleonic

Wars, well worth the effor tto recreate on the tabletop", said noted gamer Chris

Johnson. And he is right!

Although I've had an extensive Napoleonic collection for several decades, it never occurred to me to consider America's own Napoleonic War. Except for an enlightened minority of gamers, spearheaded by Allan Ferguson et. al. at Empire, Eagles, and Lions, too many of us have ignored the War of 1812.

This period particularly lends itself to campaign games. As Chris Johnson pointed out "The Niagara campaign of 1814 can be recreated in its entirety, unit- for-unit, as the two contending 'armies' were really only small divisions by European standards." This is what we have done. The following is an illustrative battle report that hopefully will encourage you to consider this period.

THE SITUATION

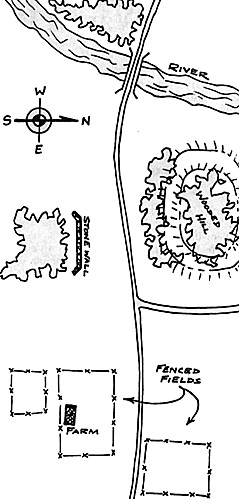

A British army is marching to the east along a narrow road on a misty morning in 1814 (see map). As their advanced scouts report that an American skirmish line is deployed adjacent to the road in the farmyard,a hard spurring courier arrives from the west to inform the British General Riall that his supply depot, located at a fort seven miles to the west (off the board) is under attack by an American column.

The British army is strung out in road column stretching from the bridge to the fork in the road and consists of the following forces (E=elite, V--veteran R=regular, M=militia):

BRITISH

-

Advanced Guard

- 95 Rifles E

71st Light V

19 Light Dragoons V

1st Brigade

- 1 Royal Scots R

100 Foot R

24 lb battery R

2nd Brigade

- 23 Fusiliers V

De Watteville R (Swiss)

Howitzer battery R

3rd Brigade

- Fencibles V

Lincoln Militia M

Rear Guard

- Chas. Brittanique R

Marines R

Royal Engineers R

General Riall had intended to march along the road to the east to attack the American base. Alternatively, he planned to turn north at the fork. With new information about an attack against his base, he must lay out his battle plan. Because of the combination of covered terrain and mist hanging over the river valley, the only American forces he sees are those within rifle range. Once the Americans deploy their visible force, the British will get an initial'free move'.

The American army, under General Scott, has the following force:

AMERICAN

-

1st Brigade

- Rifle Regiment R

9th Regiment E

11th Regiment E

18 lb battery R

2nd Brigade

- 21st Regiment R

23rd Regiment R

Volunteers 1st Volunteers R

2nd Volunteers M

Sharpshooters V

Kentucky Dragoons R

Militia

- PA Militia M

NY Militia M

Indians M

6 lb battery M

General Scott's objective is to block the British advance to the east while trying to also keep from from retreating to the west. He secretly sets up his army anywhere along the south of the road or east of the fork. Only those forces within rifle range are actually revealed except for forces in the river valley. There visibility is a mere 6 inches.

Victory goes to the side that best accomplishes its multiple objectives, taking into account casualties.

FIGURES AND RULES

First, I offer the "quick" solution to creating armies for this period. I employed the solution to see if the period was enjoyable. Unfortunately, I've found gaming the War of 1812 compelling and am now forced to take up brush to create yet another army!

Any gamer who owns a British Napoleonic army has half the forces he needs. The Canadian forces were equipped by the British, Fencibles being very- well trained elites, the other forces being of indifferent quality. it is fun to supplement British with some of the colorful allies - such as Indians and odd militia units - but this is not vital.

To get started, the American army can be reasonably represented by Portuguese! While this may be heresy to some, the Belgic shako and general appearance of the Americans is very similarto the Portuguese line who served under Wellington. What I have done is use the line infantry for both European and North American conflicts. A command stand with the blue and yellow flags of the American forces makes them American regulars, a command stand with the Portuguese flag places them in the Peninsula. It's an economical way to get going. The ill-equipped militia and volunteer units can be formed out of British Marine figures, Tyrolean Jagers,and American Revolution hunting dress uniforms. I also understand that Frontier Miniatures is putting out a line of period figures, so there might be another source.

For rules we use Generalship: The American Wars available from the author, Rte. 1, Box 397, Bluemont, VA 22012. 1 must confess to having written these rules, so my enthusiastic bias should be noted!

Two somewhat innovative aspects of the rules require explanation. Troops are rated, as shown in the order of battles, in terms of their level of training and experience. This rating indicates how easily they perform battlefield operations and what are the consequences of "critical threats", our term for morale threatening events. This is best explained with reference to the following chart:

| STATUS: | Militia | Regular | Veteran | Elite |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| initiate advance (outside 12" range) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| initiate advance (within 12" range) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| face/formation change (per facing within 12" range) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| stop retreat/rout (within 12" range) | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| stop retreat/rout (outside 12" range) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| steadying | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

A quick glance at this chart shows that the lower status units require more command points to perform an action than the better trained units. Every unit is easier to control outside of rifle range than when in closer contact with the enemy.

Command figures are given a finite number of 'command points' either based on historical rating (Scott=6, Riall=4) or on a die roll. They use these points during the course of a turn to provide grand tactical direction ("llst Brigade will attack the hill") as well as the tactical direction (rallying, charging, changing formation) shown on the chart. The command and control rule places realistic restrictions on what can be done each turn. it forces players to establish priorities since making optimal moves for all units will be impossible.

The second consequence of a unit's status rating relates to morale. A militia unit must test morale when it faces one or more critical threats. A regular, veteran, and elite test morale when facing two, three, and four threats, respectively. Critical threats are such things as enemy to the front within 12 inches (rifle range), enemy to flank, fatigue from close combat, losses, facing mounted attack, or adjacent unit routs. Each turn, the player counts the number of critical threats a unit confronts. Regulars are used to the sights and sounds of battle; simply seeing the enemy will not make them test morale. inexperienced units will test morale more often. Tabletop maneuver comes down to trying to impose more critical threats - through movement, fire, and shock - on the enemy than he is imposing on you.

THE BATTLE

Confronted with an unknown force to his front, General Riall sent the light dragoons to scout the road and adjacent fields. They spied the Kentucky Mounted Volunteers and launched an impetuous charge. Since each force was regular status and each confronted only one critical threat (enemy to the front), no morale tests were required. Instead a saber and pistol melee ensued with the British coming off decidedly the worse.

Simultaneously, long range harassing fire peppered the road-bound British column from the stone wall. (it was Scott's plan to block the British front with regulars, cut their line of communications with militia, while the volunteers provided a flexible skirmish link between these forces.) The British began to deploy to attack the stone wall, while the rearguard halted just over the bridge.

The American militia advanced up the river valley on both sides of the water. The mist clung to the ground (judge's roll each turn; 1-3 mist stays) and hid the militia advance. Riall cautiously sent the Canadian militia into the shrouded valley supported by a battery. As the mist rose, the American militia charged the British line in column. The 6 lb militia battery supported the advance with pointblank canister fire. Facing 3 critical threats (enemy to front, artillery fire, facing column attack), the Lincoln militia broke to the rear. Riall had no command points in reserve to rally them. However, the British battery escaped (it takes no command points to initiate a retreat, the assumption being a low level commander can make such a decision without recourse to his superiors - however, it would take command points to stop this command's retreat). Enjoying better luck than they perhaps deserved, the Americans advanced to seize the bridge.

Repulsed in front and back, and having determined that the wooded hill was devoid of enemy troops, Riall threw his main effort into the attack against the stone wall. He little realized this played into Scott's hands. The sharpshooters and Indians drifted back into the woods as the British turned eastward to advance against the farm. Meanwhile, a musketry duel between the American regulars and the British advanced guard flared up around the road fork. While the American gave as good as they got, some wavering in the line forced Scott to devote command points to maintaining this position. Consequently, he was unable to capitalize on his militia's success at the bridge, nor was he able to address the flanking attack developing from the stone wall. Similarly, Riall chose not to use command points to protect his rear, leaving the rearguard to fend for itself.

Spearheaded by the Guards, the British swept onwards against the farm, brushing aside the Volunteer Brigade who tried to stop them (the volunteers faced two critical threats; enemy to front, and artillery fire. They balked and retreated in order. Scott used command points to rally them outside of rifle range behind the farm). But now the British faced American regulars supported by the canister belching 18 lb battery. Further British advance was blocked. However, they inflicted enough losses on the Americans, so that Scott was unable to prevent an orderly British withdrawal off the road to the North. It had been a narrow American victory.

CONCLUSION

This game is best handled by a non-playing judge. He can ensure that realistic 'fog of war' (as well as the river mist caused confusion) is maintained. I judged two plays of this scenario. After action reports from both reveal that the British generals had a hard time of it. As one said "I've never been in this type of situation Wore, where my army is in road column confronting an unknown force." Probably, the novelty of the situation explains the curious coincidence that both generals led their main attack to the south. To this all-seeing judge, south was the one direction that would not accomplish any of the British objectives. Instead, the British should have decided to either ram straight ahead, secure their line of communications, or maul some Americans and then march off to the north.

Regarding the rules, Jim Birdseye offered the convincing thought that troops sheltered behind a stone wall should be able to confront an additional critical threat without having to test morale. He rightfully pointed out that period commanders habitually sought such positions, particularly with American militia and volunteer units. Another concern regarded canister effect against square. Jim, supported by Pat Condray's incisive wit, feels that canister should have enhanced effect against troops in square since they are so densely formed. I think that this effect is negated by the narrow front (some 60 feet for a battalion square) the guns are shooting at. This debate continues.

Regardless, I invite readers to try out this period. It very well lends itself to campaign games, including those that reflect the importance of naval operations. Currently, in our campaign, we are engaged in a flurry of ship building on the Great Lakes as the naval arms race escalates (ED NOTE: see Jon Wiliiams' articles in previous issues), just as it really did. Commander Perry, where are you now that I need you?

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VII #1

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1986 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com