In the Volume III No. 4 issue of THE COURIER, George Jeffrey presented an article about using accurate ground scales with our lead figures. He proposed measuring the depth of a figure's lead base then deriving one's ground scale from that. Thus, assuming an historical Napoleonic 3-deep line formation, which occupied about 4 yards of depth, and assuming a 3 yard minimum interval between 3- deep lines when in close column, we have a requirement to accurately represent 7 yards of depth. if our 15mm figure has a depth measurement of 7 millimeters, we can derive a scale of 1 millimeter = 1 yards (1" = 25 yds.).

For 1/300 scale Ros Heroics figures whose depth is about half that size, the ground scale would double so that 1 milimeter = 2 yards (1" = 50 ycls.). If new research or interpretations shows that the battlefield or paradeground depth should be 5 or 10 yards, ground scales would change accordingly. Likewise, if wargamers didn't care about accurate depth, they would at least be able to judge the amount of distortion they were comfortable with. Furthermore, once the ground scale was established, figure scales would become subordinate to ground scale instead of vice versa, and units could occupy realistic frontages while maintaining accurate depths.

That article presented us with a practical method of deploying our miniature Napoleonic armies in an accurate style. However, any wargamer who wished to deploy accurately was then confronted with another problem; the length of the human arm. Typical table sizes are often too small to allow us to deploy accurately while still allowing us to reach lead figures across the table. in this article I will discuss some ways to use our tables to allow accurate ground scales and to get the most out of the space we've got. These are not necessarily new ideas; most gamers have already used one or more of these ideas informally. Some of the ideas may be beyond the means of some gamers, and the final effect may still be imperfect, but at least the "accurate-scale gamer" can hope to reduce the inaccuracies caused by the lack of a chimpanzee reach.

SOME BASIC ASSUMPTIONS

Wargamers come in many different shapes and sizes; and one's reach can vary also. Wargamers have used card tables, pooltables, custom-built tables and "L"-shaped tables. For the purposes of this article I will assume the typical table in use to be the 5' x 9' ping-pong table, and the typical arm's-length reach to be 32"-36".

I will also assume that the players, in an attempt to combat the "end-of-the-world" syndrome caused by insufficient table space, use or are familiar with "off-board" troops; that is, lead figures are assumed to be present for the battle, but deployed off the table, behind the player's back, and eligible to enter the field. Many times off- board troops have their positions marked on a map or sketch.

HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION

There is an implicit historical assumption at work when players use off-table deployment. This is that those troops may enter the game but that they are in a "safe zone" or a "reserve area" where they may not be attacked. There is nothing wrong with this if one accepts that this implies that the battle will be won or lost away from the reserve area. The table becomes thus defined as the "critical area" and one need not allow for attacks into the reserve area. This is because the battle would have to be already lost before such troops could be attacked.

The player interested inaccurate ground scales wiII have to make other historical assumptions about the way a large Napoleonic battle worked if he is to rationalize an optimum usage of his table space. I do not suggest that he must lie to himself to justify his ground scale but instead maintain that current games and table usage relay a false picture of Napoleonic battles and their "critical locations". A re-examination of some Napoleonic battle deployments may change the way we allocate our table space.

Let's start with the distances between the armies in some of Napoleon's important battles. This is not an all-inclusive list, nor does it apply to every battle. I got these figures from a quick perusal through Esposito and Elting's A MILITARY HISTORY AND ATLAS OF THE NAPOLEONIC WARS. The nearest two armies started their main lines apart from each other was at Eylau, 1200 yards (and remember the winter conditions there!). At Friedland, the wings were initially 1200 yards apart but the centers were about 2400 yards apart. This is an average at Friedland of about 1800 yards (and 1760 yards is ONE MILE). At Borodino the armies started about a mile apart, and the same at Waterloo. In many of Napoleon's other battles a typical starting distance was around 2000 yards.

At Ligny, he ordered his Corps to make a change-of-front to face the Prussians. In his MEMOIRS, edited by Somerset de Chair, Napoleon stated that this maneuver brought his army to about "two cannon-shots" distance from the Prussians. In other words, the armies usually deployed well beyond effective artillery distance from each other. That is where they had a "jump-off" line, that is where they deployed and made major changes of front or formation. Had they tried such large-scale, timeconsuming maneuvers closer, they might have been attacked and dispersed before their completion, or been subjected to a long, and therefore murderous artillery bombardment. See George Jeffrey's TACTICS AND GRND TACTICS OF THE NAPOLEONIC WARS for some examples of how long it took to maneuver Brigades, Divisions and Corps grand tactically.

Once they were deployed and set, they usually headed right for their objectives. There was not a lot of fancy maneuvering or wargamer's tricks done during a 1000 or 1500 yard march towards the enemy line. Even if we assume a fast rate of 80 yards a minute for infantry (which is probably too fast when considering ground and combat conditions), we'd be talking about 13 to 20 minutes to cover the ground. If cavalry can charge 300 yards a minute and artillery can fire 1000 or 1500 yards we can understand that there would be little incentive to break up Divisions into a dozen criss-crossing battalions, changing formations and making "Napoleonic surprise attacks" every 2 minutes. It was a lot more brutal and direct than that.

Attackers and Defenders

This leads to another historical assumption: that in almost all of Napoleon's major battles there was an attacker and a defender. The attacker won if he drove the enemy in confusion from the defender's chosen positions. Likewise, the attacker didn't need to have his initial deployment line attacked to 'lose' the battle. He could lose by expending himself at the enemy position and being beaten and routing from there, or by simply losing too much while failing to take the enemy's position. That would leave him no alternative but to fall back at least a mile from the enemy positions, which, coincidentally, was often where his jump-off line was in the first place.

This is important, because it differs greatly from the typical wargamer's "encounter battle" where the two sides start at each end of the table and march towards a mutual collision in the middle of the table. if the battle is seen as an "attacker-defender" situation, we then have one "critical zone" which is the defender's position or line. It is important to show the depth of the defender's position, since the position isn't really taken while the defender has reserves there who can retake their lost positions, or who must be driven away to assure victory.

For example, driving back the enemy first line is of little use if he has a second line within canister range whose guns can chew up the attacker. Thus, the defender's side should be portrayed showing the original location and in enough depth to show any troops who might seriously threaten to retake those original positions.

If the defender can win by holding his positions, he has no incentive to cross 1500 yards of artillery ground and attack the "attacker's" lines. He can beat up the attacker on his own turf. if that leaves the entire attacking army in a state of near collapse and rout, a 1500 yard advance from the defending positions (as at Waterloo) is more of a pursuit than an attack on the enemy rear. The decision was reached on the defender's lines. The defender may decide to become the attacker the next day; but the character of this battle would be decided by the actions on or behind the defender's lines.

The attacker, on the other hand, is concerned with reaching the defender's line to fight and win there. Should he be hurled back from the lines or back across the artillery ground he would re-group and try it again. Thus, the artillery-ground was not a fighting or maneuvering area. It was instead an attrition space, across which armies advanced or retreated to get to or from a non-fighting area to a fighting area. The attacker would leave a non-fighting deployment area, cross the artillery-ground, then reach a fighting zone.

The fighting zone would begin at the defensive line and extend across the depth necessary to secure the defensive line. Success meant driving the defender from that zone (which naturally meant casualties). A defender who was driven from a deep position was often in such confusion that an attacker's pursuit could bring large dividends to the pursuer, but this was an after-effect rather than the cause of defeat. if an attacker were unsuccessful, he would retreat and start again.

At Borodino the distance between the French and Russian reserves was about 4000 yards. Armies often kept reserves a mile or more behind their own front lines; thus if they did lose their front line, their reserves would be out of artillery range of enemy batteries who might set up there, and the reserves would also have enough time and space to set up a rear-guard if necessary. Front-line fugitives would be able to rally without carrying the reserve formation with them. We might sum things up by saying there was no hard-and- fast rule about army deployment, but for our game purposes, we can figure that a "typical" layout would have about a mile (1760) yards between the armies (outposts, etc. could be closer) and about a mile of depth for each army, a total of more than 5000 yards. More would be perfectly authentic, while if pushed for a minimum we might get away with having 1000 yards between the armies and 1000 yards deploying depth for each, a total of 3000 yards. Let's now consider the problem of transferring these distances to the table top.

USING THE TABLE TOP

Now that we have an idea of how to obtain accurate ground scales, what areas were taken up by historical battles, and the functions of different sectors of the battlefield, we can look to simulating this on a table. The 5 x 9 ping pong table represents about 1500 x 2700 yards for 15mm figures using the accurate imm = 1 yard (1" = 25 yards) ground scale. For 1/300 scale Ros Heroics figures, using I mm = 2 yards (1" = 50 yards) the table is 3000 x 5400 yards. Let's look now at 1/300 scale players, followed by tables for 15mm players.

The 1/300 scale figures can use a ping pong table as is if the player is willing to use the minimum suggested distances of 1000 yards between the armies and 1000 yards for each army's deployment. If we use as an historical rule of thumb that we can deploy a Corps of about 20,000 men, in depth, for each mile of front, we can use accurate depth and have enough frontage on our single table for about 60,000 men to each side. Clubs able to put two ping- pong tables together can accurately place armies of over 100,000 men to each side. Traditional off-board maps can also be kept for more reserves. (Those gamers who do have tables of 6' depth and reaches over 36", would find that this gives about 3600 yards of depth, or 1200 between armies and 1200 for each side.)

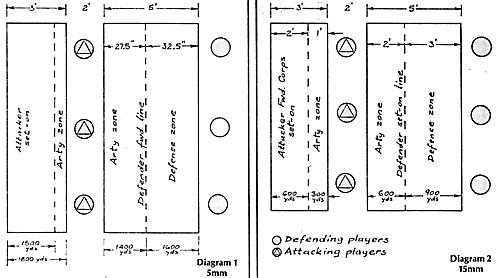

For the 1/300 scale Napoleonic game a table depth of 3 miles would require more than 8.5 feet; a problem if our arms reach only 3. One can take care of this by using an extra 3' wide table behind the attacking players (see diagram 1). If we assume players need 2' of space and have a 5' table and a 3' table we would need 12' of space, 11' if we substituted a 2' table for the 3' table. An 8' depth would mean 4880 yards, or 1626 yards between the armies and for each side. For that we would give about 32.5 inches on the 5' table to the defender, which is nearly a mile. if he is driven off the table, which is to say a mile or more from his front line he will have lost the battle. The remaining 1424 yards (27.5") on the 5' table would be the artillery zone through which the attacker will pass to reach the 1626 yard deep fighting zone of the defender's lines; as such no attacking figures would start on the 5' table.

The army of the attacking players would be deployed behind them on the 3' deep table, representing over 1800 yards. (The first 6" or so won't be occupied, so the 1424 yard gap between the armies will be increased to a mile.) This is the attacker's initial deployment zone, where he can deploy his army in formations of choice and prepare his attacks. The two tables are assumed to be joined as one 8' table, so movement from one table immediately goes onto the other. This is a point that many players object to on grounds of "taste". They wish to see all of the figures on the table in front of them, or worry about the enemy moving from one table to another.

However, in this case, for the defender to move from his table to the attacker's table means he has held his own line, beaten the enemy back from it and then moved four-fifths of a mile into the attacker's reserve zone. There is a good chance the battle would be over by that time. The attacker will see his troops across the artillery ground and at the enemy lines. And if he turns around, he'll see his reserves posted behind him. The 3' table can be landscaped, too. Players are still free to use off-board map locations and if the defender has room he could even use a 1' or 2' table behind him if he wishes to deploy deeper reserves, or have space to show rallying troops or a rearguard being formed.

The 15mm player will need to look more at the minimum distances than at the "typical" distances. This means that we are looking for about 3000 yards. The most important point is to give the defender defense depth, the next in importance is to separate the armies and the third priority is space to lay out the attacker's lead. This is because the critical fighting will take place on the defender's lines and because attacker positions can be indicated on a map easier than can the artillery ground or defender's defense area. In a 15mm game we must also examine the artillery zone and be sure that the deadlier zone of 500 yards and below is represented in front of the defender's position. The longer artillery range is still necessary, but less likely to have troops from both sides in it, and therefore it is less critical that it appear on the defender's table.

So a typical table arrangement might find players on both sides of a 5' deep (1500 yards) table (see diagram 2). Behind the attackers would be a 3' deep (900 yards) table. On the 5' table, the defender's line of battle would have about 900 yards (3') of table. He would use off-table maps for any reserves or rallying troops further than that (although players with extra space in the garage might be able to add a one or two foot table behind the defenders as well, at 300 yards per foot). The remaining 2' (600 yards) of the table would be the beginning of the artillery ground, and the deadlier half; canister range for 12 pounders.

The 3' table behind the attackers represents 900 yards. The first 12 or 18 inches (300-450 yards) will be left initially empty as the remainder of the artillery ground. Added to the 600 yards from the other table gives us the necessary interval between armies. Note that players may decide during the game to brave artillery losses and occupy portions of the "artillery ground" we are concerned here with proper initial deployments that lead to proper initial attacks. The improper current practice often sees large deployments within close roundshot range, followed by a mad mutual rush towards the enemy to reduce artillery losses!

The remaining 450-600 yards gives the attacker enough space to deploy at least his front line of Corps, perhaps more, on that table. This shows the attacker and defender the initial attacking line-up that is coming towards the defender's fighting zone. Further attacker deployments or reserves would be shown on off-board maps. 15mm players will need twice the table frontage as 1/300 players; thus one table for 30,000 men to the side, three for 90,000. Again, joining clubs helps, since they can provide more figures to get the bigger games as well as finding more space to enable more tables to be used.

Players may be able to alter some of these numbers. For example, if the players are willing (or able) to squeeze into 18" instead of 2', another 300 yards is gained for the 15mm game. Players who have room for a 4' rear table, or can put a 2' table behind the defender as well as the attacker can get more battle room. Is it easy? No. Is it always possible? No. Does it give a perfect historical simulation?

Not perfect, no, but certainly closer to history than much current wargaming practice. For the Napoleonic wargamer who is interested in how the Napoleonic battlefield looks with an accurate ground scale and thinks this might give him new insights not available in his current game, is it worth the attempt? Definitely!

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. V #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1984 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com