On 21st June 1813 Wellington's Peninsular army won the

famous battle of Vitoria and cleared the French out of Spain.

On 25th July 1813, scarcely more than one month later,

Wellington came as close to defeat as he had ever been in

his career, and was all but pushed back across the Ebro by

an energetic and unexpected French counter-offensive.

On 21st June 1813 Wellington's Peninsular army won the

famous battle of Vitoria and cleared the French out of Spain.

On 25th July 1813, scarcely more than one month later,

Wellington came as close to defeat as he had ever been in

his career, and was all but pushed back across the Ebro by

an energetic and unexpected French counter-offensive.

TYPICAL PYRANEES SCENERY

Why was the triumphant army of June so nearly overthrown in July? How did the beaten French rally themselves so effectively for their telling riposte? These are interesting questions which illuminate a number of factors worth incorporating in Napoleonic wargames.

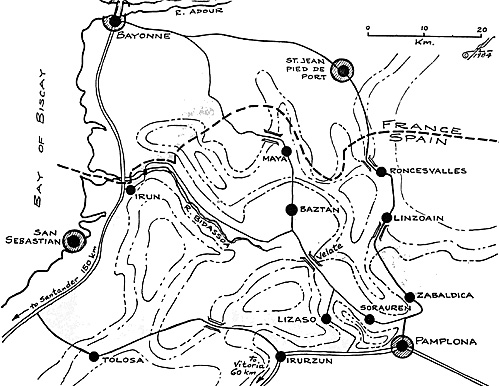

In the first place, Wellington's army fell to pieces after Vitoria almost as much as the French themselves. The fabulous booty captured in the battle distracted the soldiers and posed enormous disciplinary problems for the officers. Wellington was therefore unable to make an effective pursuit. The French, by contrast, were retreating upon their reinforcements and depots. They found well-stocked fortresses at San Sebastian, Pamplona, St. Jean Pied de Port and (especially) Bayonne. Secure within this "quadrilateral", they could reorganize their army and prepare to resume the offensive. Napoleon entrusted the task to one of his most energetic marshals--the greedy, obnoxious but crudely forceful Nicolas Jean de Dieu Soult, Duke of Dalmatia.

Even more to the point, perhaps, was the nature of the terrain. This was the area of the Western Pyreneesan impressive mountain barrier cutting across all communications apart from the coast road running either side of Irun. At Irun, however, there was the Bidassoa estuary to act as a military obstacle of a different kind. Nowhere along the frontier between Spain and France was it easy to maneuver large bodies of troops, and for wheeled vehicles or artillery much of the ground was totally impassable.

Wellington had seen mountains before, especially in Portugal, but in the Pyrenees the mountains were higher and more continuous. They could not be skirted by maneuver, and therefore imposed "mountain warfare" conditions upon the entire operation. This meant that movements were channelled along the 'grain' of the country-along roads at the bottom of steep-sided valleys, or along relatively flat but narrow and exposed ridgeIines. As soon as movement was attempted across the grain--up or down hillsides--it became very slow and dispersed.

In tactical terms all this offered some dramatic advantages to a defender. Relatively small bodies of troops could offer prolonged resistance at key passes or ridgelines. The steepness and vegetation of the terrain prevented close- order drill, so an attacker was forced to approach in disjointed skirmish clouds. Lengthy and inconclusive fire-fights usually followed, with occasional bayonet charges, perhaps, by units no bigger than a platoon. On several occasions in 1813 a brigade was able to hold up an army corps for half a day or even longer.

On the other side of the coin was the difficulty of reinforcement and the poor state of lateral communications which a defender had to overcome. If an outpost was attacked, it would be an eternity before any help could be sent up from supporting forces in the valleys below, let alone from flanking formations. The theatre of war was no more than 50 kilometers wide as the crow flies, but much more than twice that as the soldier marches. Command and control was exceptionally difficult, since the two armies were so widely dispersed in such inhospitable ground.

An attacker also enjoyed many possibilities for enveloping and surrounding enemy outposts. Although difficult and steep, the ground was rarely steep enough to prevent movement on foot altogether. Infiltrations were therefore possible through gaps in an enemy line. This was made all the more possible by the frequent mists and low clouds which often hung over the mountains-even in July. Several of the passes were over 3,000 feet above sea level-around twice the altitude of Wellington's defensive position at Busaco in 1810. On a number of occasions a surprise attack was able to overwhelm outposts before they had realized that the attackers had approached to close range under cover of the mist.

In July 1813 Wellington halted his pursuit on the crest of this mountain line, and set about reducing the two fortresses in his rear-San Sebastian and Pamplona. He covered these two operations by placing the bulk of his force in a defensive screen along the Spanish frontier--in strong tactical positions, but dispersed and vulnerable in the ways we have already noted.

Soult Attacks

On 25th July Soult was therefore able to launch two powerful attacks against the Eastern flank of the position, while Wellington remained preoccupied on the sea coast, watching the attempted storming of San Sebastian.

This was a day of disaster for the allies. The storm of the fortress ended in a bloody repulse. The attack on the Col de Maya succeeded in capturing a key British picket position, thereby unlocking the whole line. On the two shoulders of the Roncesvalles position the allies did admittedly hold their ground well at first-but at nightfall the local commanders could not overcome their fears of being outflanked, and they fell back to the south.

Wellington himself was caught strategically wrong- footed, and needed several days to effect a significant concentration in the path of the advancing French. It was only at Sorauren on 30th July that the French were finally defeated. They had failed to capture a strong hill position by frontal attack, and Wellington had been given a chance to reinforce it and counter-attack. Even so his Light Division was still maneuvering around Irurzun ' far from the battlefield, while general Hill's command was still being pushed back by enemy flanking moves around Lizaso. The whole episode was certainly a "near run thing" for the alIies.

Wellington managed to getaway with it in the end, and Soult's starving army had to retire into France with its tail between its legs. When it made a second attempt to break into Spain, across the lower Bidassoa, it was defeated on the first hill position, near Irun, by a force composed almost entirely of Spaniards-one of the few occasions in the war on which the Spanish forces distinguished themselves.

Wargaming the Real Campaign

When we turn from the real campaign in the Pyrenees

to the ways in which it can be wargamed, we find that

fascinating games can be designed at both the strategic

and tactical levels of action. Let us now consider these in turn:

The strategic game must be played with maps and hidden movement which is possible,although not easy, with only two players. I have played the campaign in this way, with London-based wargamer John Davis, over a series of five meetings. The main necessity is for both players to be honest about the hidden moves they make, and about what forces can be seen from the enemy's outpost lines. Both sides are assumed to see the enemy outposts at all times, but what else comes into the range of vision of each outpost will depend on the weather, the contours and the enemy moves with his main forces. When the enemy player thinks he has a force which can be seen by your outpost he rolls a concealed die:

- 1- your outpost reports to you that it has seen a force 20%

smaller than the real one

2/3- your outpost turns in a correct report

4- your outpost reports 50% more than it actually sees

5- your outpost reports 100% more than it actually sees

6- your outpost reports 300% more than it actually sees

Thus it is your enemy who is responsible for your scouting work, just as you are responsible for his. He will not tell you how accurate your reports have been, thus simulating the tendency to exaggerate which was a common feature in Napoleonic warfare.

It is better if all this can be done by an umpire, who will also be responsible for the movement of messages. In the mountains the transmission of scouting reports to commanders, and then the distribution of orders to units, could often take many hours. It formed an important part of the strategic difficulties imposed by the terrain, and helped to achieve effective "command paralysis" on a number of occasions.

All wargames in which one player is responsible for more than one separate force will always suffer from a certain lack of realism. They always ask the player to "be" more than one person at a time. In "Wargame Developments" recently we therefore played a large game of the Pyrenees campaign in which each separate force was given a different player to command it.

There were thus ten French players split between six playing cells--one for Soult's HQ, one for each of four corps, and one for the sieges of Pamplona and San Sebastian. On the British side there were cells for Wellington's HQ, each of five independent commands and the two sieges, making eleven allied players. Play was coordinated and adjudicated by a team of eight umpires, making a total of 29 participants in all. Nine playing rooms were occupied by this mass of dedicated gamers, who worked hard to play out four days of the battle in the space of twelve hours of real time (including briefing, setting up, two meals, debriefing and clearing away).

Players were asked to issue orders for their forces up to dawn on 25th July 1813, in advance of the game. The umpires then determined what tactical contacts would result from these movements, reckoning on rates of movement for infantry (in Kilometers per day's march) as follows:

- On "Very Main Roads" (coast road and in the

Pamplona plain) 25-35

On 'Useful Main Roads' (those marked by my map) 20-25

DEDUCTION for crossing a 'pass' 5

On a 'Track' (many mule roads criss-cross the area, not shown on my map) 15-20

DEDUCTION for crossing a 'watershed' 5

Cross Country on flat ground or along a ridgeline/ watershed line 10 15

Cross country "against the contours" 5-10

A random factor was added to movement depending on the quality of the local Basque guide attached to each force. A bad guide could get you badly lost (as several real generals discovered in 1813!).

When there was a tactical contact, a "tactics" umpire would ask each side for the details of their forces in presence (making allowances for column lengths and hence delays in deployment). Local maps would be shown to players, as well as perspective sketches of what they could "see".

On this basis the players were supposed to think themselves into the shoes of a Napoleonic commander on the spot, and make snap decisions for what they wanted to do (usually they were given one minute to make up their minds, after the situation had been explained to them). Each battle lasted for about half an hour of real time, as tactical umpires moved back and forth between the two opposed sides collecting decisions and other information about what was going on.

A SECTION OF THE ORIGINAL MAIN ROAD FROM RONCESVALLES TO

PAMPLONA AT LINZOAIN

A SECTION OF THE ORIGINAL MAIN ROAD FROM RONCESVALLES TO

PAMPLONA AT LINZOAIN

The results of combat were achieved by a "free kriegsspiel" system, based on the umpires' "feeling" for the combat odds, plus the score shown on one decimal dice (high numbers favor the French!). In this way we were able to get through about six large battles and several more smaller ones within the time allotted, without holding up the strategic action too much. Admittedly, there were a few loose ends, and the sieges cell was badly disappointed that such a short time was played (it didn't give them much time in which to develop a three month blockade!); but by and large we managed to get an overall strategic decision before supper.

In the game Soult attacked with almost equal forces along the coast road and over the Maya pass. After some exciting combat on each axis he was held by the allies and persuaded to retreat. Near Baztan, however, some French forces were able to cut the main road to Irun for a while, which endangered Wellington's lateral communications and almost did for him (in a paper dart duel as he arrived with his HQ in the midst of some French cavalry pickets).

In my game with John Davis I had used 5mm miniatures for the tactical contacts, while in the large scale WD game it was all done by explanations and perspective sketches (compare my postal battle of 1859 in 'Courier' Vol. 5 No. 1). An alternative would be to use 15mm or 25mm miniatures on a scale terrain. I would not wish to play this sort of game myself, since I would find too many problems of scale and of rulesconcepts; but if that is your particular area of interest, then I would say that there are many unusual features that you could incorporate into such a game.

If the groundscale is 1mm = 1 meter, then a scale model of Maya ridge will be about 3,000 mm long (some ten feet), but no more than about 25mm (one inch!) wide along the crest-line. On either side it will fall away very steeply indeed, although the crest-line itself will have undulations of only a few tens of millimeters up and down. This will make a very unusual wargame table indeed-but then the real battle was fought under very unusual conditions indeed. The miniaturist will have to look closely into his rules for vertical movement, for skirmish action, and for misty weather, before he will be able to re-fight battles like Maya on the table-top. It will certainly not do for him to assume that this is "just an ordinary battle but with a few more hills"!

There is the challenge--i.e. can you simulate Wellington's art of mountain warfare, 1813, on maps or on the table top, without falling into the trap of treating mountain warfare as just another variety of "normal" Napoleonic warfare? If you can, I am sure that you will find it is stimulating, interesting and-above alldifferent!

UMPIRES KEY TO GUIDES

When players apply for a guide, umpires give out top card from the pack, and mark it for the village of origin of the guide. The player then reads the card and either accepts or rejects the guide's advice. No more than 2 guides per village may be rejected by any one force. Beyond that they get no guides from the village. Only one guide can be consulted at a time.

Retrieve cards and try to keep the set of guides for each village together. Remember that the effect of the guide ceases when he has moved more than 7 km from home.

POSSIBLE OUTCOMES FROM THE GUIDES

- A: Excellent guide. Force does not get lost but

takes 10% off its time of arrival.

B: Moderately good guide. Force doesn't get lost. Arrives on time except on cloudy-rainy nights 10% delay.

C: Shifty character/smuggler/spy for the enemy. Roll nugget. For 8/9 behaves as 'A'; for 6/7 as 'B'; for 0-5 as 'F'.

D: The village idiot. It rapidly becomes clear that he cannot help the force, so is allowed to lope home, grinning inanely, after 500 meters.

E: Well meaning but rather confused guide. Has difficulty with the language. Force gets lost for 0-2. Otherwise arrives with 10% delay.

F: Donta Speaka the Lingo, and probably rather dim anyway. Force always gets lost (except on main roads or 'relatively flat ground').

OUTCOME OF MOVEMENT WITHOUT A GUIDE

(or with a viIlage idiot!)

On 'Very Main Road' or 'Useful Main Road' or 'Relatively flat ground': always find the way, but delay between 0-25% (umpire's discretion).

On 'Road or Track' always find the way in good weather in daylight. Lose the way for 0-1 in mist, rain or darkness. Delay between 0-25%.

Cross Country get lost for 0 in good weather, 0-2 in other weather. Delay between 0-35% (umpire's discretion).

GETTING LOST

If a force "gets lost" it takes a wrong turning:

- 0-1 90 degrees right

2-4 30 degrees right

5-7 30 degrees left

8-9 90 degrees left

Throw again for time of wrong turning: 0-2 after 1/4 of march 3-5 after 1/2 of march 6-9 after 3/4 of march ... or at umpire's discretion throughout.

UMPIRE SECRET

List of Local Guides

No & Name and Grade

1 Xavier D

2 Guyonne E

3 Juan B

4 annes A

5 Ramuntcho F

6 Sanz C

7 Sibert B

8 Alaric E

9 Albin A

10 Aldebert B

11 Aldric B

12 Aiienor C

13 Ala D

14 Aloara E

15 Andeol E

16 Archibald F

17 Arthaud F

18 Aubree E

19 Aymon E

20 Bastian D

21 Bertrane C

22 Brune B

23 Colomban B

24 Darnia A

25 Doulce D

26 Elzear F

27 Emilian F

28 Enric E

29 Esteban C

30 Esteve B

31 Fabian A

32 Fannin B

33 Fereol A

34 Foolques B

35 Fortunat B

36 Franca C

37 Gaietana D

38 Galia E

39 Gaudens F

40 Gaston F

41 Girazid A

42 Grazilla E

43 Grinaud E

44 Isaro F

45 Jordi D

46 Jules C

47 Faur B

48 Mage B

49 Magnetic A

50 Magali A

51 Matte B

52 Malid B

53 Malvy C

54 Xavier D

55 Margam E

56 Maetge F

57 Oliver F

58 Orlando E

59 Pascual E

60 Carlos C

61 Edmondo D

62 Huez B

63 Pedro B

64 Panco A

65 Pievre A

67 Miguel B

68 Xavier C

69 Rambert D

70 Ramon E

71 Rannunt E

72 Regis F

73 Remain F

74 Romanic A

75 Saby B

76 Sanz B

77 Sebastian C

78 Steve D

79 Tony E

80 Xavier E

81 Ramuntcho A

82 Xavier B

83 Urbain B

84 Valens C

85 Veran D

86 Felipe E

87 Hernandez F

88 Jose F

89 Fernandez B

90 Pietro B

GUIDE CARD EXAMPLES

The player must decide on the bases of the evidence shown on the cards themselves, whether he will let his force he navigated by these characters! The cards often give fairly accurate indications of what the player can expect - but not always! See "Umpires guide" for details.

17 ARTHAUD A student of Basque literature. The local priest. Very pious

gent.

14 ALOARA Rather a confused person, but with a winning smile.

55 MARGAUX A worldly-wise farmer's wife who is especially good at

explaining recipies and cures for bunions.

32 FANTIN A strapping Basque peasant. Keeps goats and hens. Hard to

drag away from them, in fact.

75 SABY Crack Shot with a squirrel gun, but likes his vin rouge.

24 DAMIA Local postman. Anxious to please.

67 MIGUEL Local librarian. Keen on books. Willing.

54 XAVIER Can't stop picking his nose & scratching; but has clearly lived

near here and in the outdoors a long time.

78 STEVE Not easy to follow what he says - but he is obviously keen to help.

60 CARLOS Showy clothes, earrings. Smells of garlic. Keen to get a reward for services to you.

29 ESTEBAN Overwhelmingly willing and ingratiating. A gleam in his eye shows shifty intelligence.

FURTHER READING

Apart from the standard works on the Peninsular War (Napier, Oman, Weller and Glover) there is a specialist study of the Pyrenees campaign by F.W. Beatson-'With Wellington in the Pyrenees' (London 1914? n.d.)-which is highly recommended. After Beatson, Oman is the best.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. V #5

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1984 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com