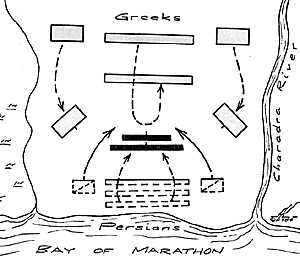

In the autumn of 490 B.C., the Persian army that landed on the plains of Marathon was more varied in composition, hence potentially more capable, than the pure heavy infantry formations of the Greeks. The Persian army, in addition to infantry, possessed a large number of archers and some cavalry. The Athenian army arrived for battle 10,000 strong and occupied a strong position on raised ground. They opposed the Persians whose force at Marathon was an estimated 15,000. Upon observing the Greek army, the Persians deployed between the right bank of the Charadra and the Little Marsh (see fig. 1) so their line was parallel to the shore of the bay, Marathon. The Persian front on the plain was too long for the Greek hoplites to cover in their usual eight deep formation. To compensate, theGreek council of war decided to spread theirformation by reducing the center to four ranks while maintaining eight on the flanks. Both armies had anchored their flanks on the streams with steep banks.

As soon as the battle line had been formed the order to attack was given and the Greek hoplite formations moved forward. The advance was slow at first since the two armies were about a mile apart. However, to minimize the effect of the Persian archers, the Greeks covered the last 200 yards or so at a rush.

According to custom, the Persians had deployed their best troops in the center. This placement combined with the already thinned Greek ranks allowed the Persians to push the center back. The Persian success in the center drew their army into a convex line, while the deeper ranked Greek wings, unshaken by the assault on the tribal levies on the Persian flanks drew inwards. This effect was probably anticipated by the Greek commanders. The result was a double envelopment with no room to maneuver for the Perians. The Persian army was trapped and defeated.

Ths advantageous use of terrain and the battlefield disposition of the Greek army resulted in a victory for a less progressively developed and quantitatively inferior force. The Battle of Marathon illustrates how the armies of the Greek city- states won battles on ground of their choosing and denied the Persians tactics that would fully exploit their capabilities as a more diversely composed army that had conquered all of Asia Minor.

Success

The successful generals of ancient classical warfare were acutely aware that great care was necessary in choosing the field of battle and in the disposition of one's forces. This same care is necessary for modern wargamers with ancient armies. With the advantage of some two thousand years of military history over the ancient generals, the modern wargamer has the tendency to use maneuver to compensate for an initial maldeployment or a concentration of missile fire to negate higher quality troops. These techniques are more applicable to contemporary warfare, and are often overcome by a direct and quick attack that leaves no time for major troop shifts.

The modern wargamer often neglects the real and necessary skills that brought victory on the ancient battlefield. A review of the ancients' observations on disposing one's forces for battle may prove usef u I to the ancient wargaming general battling on table tops.

Flavius Vegetius Renatus, a Roman of high rank, wrote "De Re Militari", a synthesis of ancient manuscripts, Roman military regulations and customs. His treatise became the universal text for the warrior-kings and generals of the middle ages. His identification and observations on various battle formations are inclispensible to the modern wargamer.

Before discussing the various formations some general comments on terrain are necessary. In the selection of a battlefield, it is extremely important to protect the army's flanks. Physical obstacles such as river or marsh make ideal anchors for one's line, and it is sometimes necessary to allocate additional cavalry to cover an open flank. One obvious consideration in the choice of terrain is to occupy the highest ground.

Most wargaming rules rightfully enhance the fighting capabilities of troops on high ground. Weapons thrown from a height strike with greater force; and the soldiers above their opponents can repulse and bear down on them with greater impetuosity. In order for infantry to stand against cavalry, it must choose a rough, uneven, or steep hill location to break- up cavalry charges.

Or, if on the contrary, you expect to use your cavalry, you would be wise to select ground that is higher, level, and open - without any obstructions such as woods or morasses.

Other uses of terrain allow economy of force tactics such as light infantry in woods. One can use obstacles to pin or limit enemy maneuver space. A battlefield with a number of terrain obstacles or terrain that wil significantly slow portions of a deployed army offers opportunities for additional flanks open to attack.

In the matter of the disposition of the armies, some factors that had to be considered by ancient generals but do not figure into modern wargaming rules are the sun, dust, and wind. The sun in a soldier's face hampers vision and dazzles one's sight. If the wind is against the troops, it turns aside and blunts the force of their weapons, while it assists those of their opponents. The dust driving into the soldier's front fills their eyes and blinds them.

The ultimate aim was to have the troops so disposed as to have these inconveniences behind them, and directly in the enemy's face. The dedicated ancient aficionados who may wish to use these weather elements might consider a minus factor for such ill disposed troops on the initial melee.

Seven Different Formations

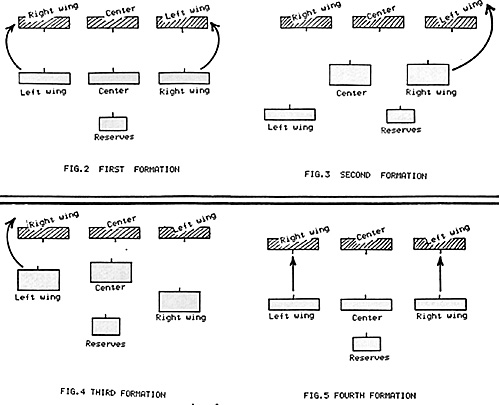

Vegetius identified seven different formations in which an ancient army could be drawn up for a general engagement.

The first formation is a linear rectangle (fig. 2). This formation

is useful only on level ground, where lines may be held intact

without interference from hollows or ground irregularities. if

the cohesiveness of the formation is broken at any point due

to uneven ground, woods, or steep hills, it is that weakened

segment of the line that will be exploited and pierced by the

enemy. Since the reserve must be able to support either wing against an enemy's

possible envelopment tactic, it should consist of cavalry or

light troops for quick movement. This formation should never

be used unless enough troops are available to attack the

enemy on either or both wings.

The first formation is a linear rectangle (fig. 2). This formation

is useful only on level ground, where lines may be held intact

without interference from hollows or ground irregularities. if

the cohesiveness of the formation is broken at any point due

to uneven ground, woods, or steep hills, it is that weakened

segment of the line that will be exploited and pierced by the

enemy. Since the reserve must be able to support either wing against an enemy's

possible envelopment tactic, it should consist of cavalry or

light troops for quick movement. This formation should never

be used unless enough troops are available to attack the

enemy on either or both wings.

A wargamer should make use of this disposition only when his forces are better and more numerous than the enemy's, and when it is within his capability to attack the flanks. This linear formation is particularly suited to Greek hoplite or early Roman armies. These armies possess numerous and sturdy infantry.

The second formation (fig. 3), and the formation that I have found most useful, is the echeloned army. With good quality troops, this formation can be used against quantitatively superior forces. As the armies are approaching for melee, your left wing must be kept back from the enemy's right side and out of range of their arrow and other missile fires.

Historically, the left side of a soldier, and the left wing of an army, were traditionally the weak side because it was hampered by the shield and other armor. Consequently, the left wing was usually the defensive wing; the right wing, the offensive. if the right wing is relatively protected by terrain, the echeloned left wing will defend the army's main body. For wargaming the echeloned left side should be open to the side forcing a greater distance to be traversed by the enemy's cavalry for a flank attack while your army moves quickly to close with and defeat his main body.

The right wing must advance obliquely upon the enemy's left and begin the engagement. Here, you must use your best cavalry and infantry to surround the enemy's left and make it give way, so that you may fall upon the enemy's rear. If you give ground on the initial melee and the attack is properly reinforced, you will undoubtedly gain the victory while your left wing which continued to advance at a distance will remain untouched and poised to counter a flank threat.

Additionally, an important point is to advance the left wing so it will always be capable of countering flank attacks to the center. Most of Alexander the Great's battles were modifications of this method in which he fought with a concerted infantry push in the center to create an opportunity for a decisive cavalry charge on the right. Reserves are held to support the left wing if required, or if the enemy anticipates your maneuver on the right wing.

The third formation (fig. 4) is like the second, but not as good. This formation has your left wing attack the enemy's right. This movement should be used only when your left wing is stronger than your right and reinforced with your best cavalry and infantry, and the enemy's right isweak. An additional consideration is favorable terrain on the left with open terrain and a cavalry threat on the right. The right wing composed of your worst troops should remain at a distance from the enemy's left wing and avoid their arrows and other missile fires. These troops should also evade a sudden attack for melee. The latitude in composition for the wings and center of this formation makes it an excellent choice for virtually any ancient army.

The fourth formation (fig. 5) is employed as you move your army slowly to the attack in battle lines. As you come within two hundred paces (Wargamers Research Group rules), both of your wings must be ordered to unexpectedly quicken their pace and rush to the attack. This sudden, simultaneous onslaught on both the enemy's wings should surprise him and may catch him in the middle of troop realignment from an initial maldeployment.

A word of caution, this move may be hazardous to the health of your army. For if it fails on the first charge, the enemy is given an extremely good opportunity to attack your wings which are separate and without support from your center. This method is recommended in situations when the opponent has unwisely placed low quality troops on both flanks allowing for a quick melee and rout.

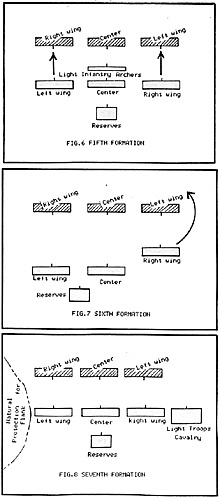

The fifth formation (fig. 6) resembles the fourth but plans

for the use of light infantry and archers before the center to

cover it from the enemy. With this precaution, the wargamer

may safely follow the attack as in the fourth formation with a

protected center. This time if the attack fails the center is in

strong position to move to the wing that showed success with

support from the light infantry. This maneuver still has some

risk and should not be tried against an experienced

opponent. The maneuver's major flaw is the lack of quick and

mutual support to either wing. The one or two moves to bring

up the center may be too late for the beleaguered wing.

The fifth formation (fig. 6) resembles the fourth but plans

for the use of light infantry and archers before the center to

cover it from the enemy. With this precaution, the wargamer

may safely follow the attack as in the fourth formation with a

protected center. This time if the attack fails the center is in

strong position to move to the wing that showed success with

support from the light infantry. This maneuver still has some

risk and should not be tried against an experienced

opponent. The maneuver's major flaw is the lack of quick and

mutual support to either wing. The one or two moves to bring

up the center may be too late for the beleaguered wing.

The sixth formation (fig. 7) is very good and almost like the second. It is used when the wargamer cannot depend either on the number or the morale of his troops. If made with good timing and spatial judgment, the wargaming general has a good chance for victory. As your line approaches the enemy, advance your right wing against the enemy's left wing and begin the attack with your best cavalry and infantry. At the same time keep the rest of the army at a great distance from the enemy's right, extended in a direct line. Menaced by your left wing, center, and reserves, it is risky for the enemy to draw upon his right and center to aid his left wing in resisting the attack of your strong right. It is a formation often used in an action proceeding from an attack while on a march.

The seventh formation (fig. 8) owes its advantages to the nature of the ground and like the sixth formation will enable the wargamer to gain victory while fighting with a numerically and qualitatively inferior army. The prerequisite for this formation is that one of your flanks must be anchored on a physical obstacle such as a river, lake, impassible morass, or inaccessible broken ground to the enemy. The rest of the army must be formed ' as usual, in a straight line and the unsecured flank must be protected by your light troops and all your cavalry. Sufficiently defended on one side by the nature of the ground and on the other by a double support of cavalry and light infantry, you may then safely go into battle.

Considerations Some considerations to be kept in mind will insure success. if you intend to engage with your right wing only, it must be composed of your best troops. And, the same consideration applies with respect to leading the action with your left. Or, if you intend to penetrate the enemy's line, the wedge which you form for that purpose before your center, must consist of the best disciplined soldiers. Victory in general is gained by a small number of men.

The concept of this formation was used by Julius Caesar at the Bttle of Pharsalus48 B.C. Outnumbered by Pompey'sarmy, Caesar anchored his left flank on the River Enipeus and placed all his cavalry on the right flank stiffened by light infantry and an additional eight cohorts. Caesar's cohorts pushed back Pompey's larger cavalry force and threatened to encircle Pompey's army. Caesar won with a smaller army.

The wisdom of the ancient generals as well as for modern wargamers is nothing more than the art of choosing an army's disposition in consonance with the enemy's composition and disposition, terrain, and how you like to fight your army. Like any art the simplicity is achieved from technical subtleties and experience. By a better understanding in the nuances of ancient warfare, your selection of the initial disposition and use of terrain will limit your opponent's response time, and they will be mystified to find the battle lost before the first arrows are unleashed.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. V #4

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1984 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com