THE SITUATION

Sunday, October 25th, 1812. The Russian Campaign. An

outpost skirmish north of the River Lusha could have

occurred as described below.

Sunday, October 25th, 1812. The Russian Campaign. An

outpost skirmish north of the River Lusha could have

occurred as described below.

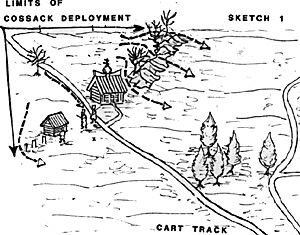

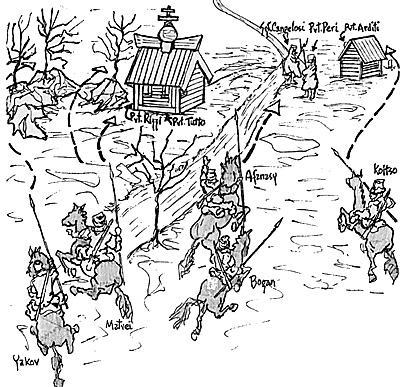

Sgt. Cangelosi (A class, veteran) and four privates, IV French Corps, Prince Eugene commanding, have turned a stout log chapel into an improvised blockhouse. At this moment, Pvt.'s Tutto (B class) and Rizzi (C class) are on guard inside the chapel. Beside the broad cart track, Sgt. Cangelosi and Pvt. Peri (C class) await the result of Pvt. Arditi's (B class) foraging at the hut across the track (Point X in Sketch 1).

THE RULES

Paddy Griffith's Napoleonic skirmish rules allow 54mm figures to make 14 inch mounted moves with 28 inches at the gallop (scale: 1" to 1 meter). Suitable for light cavalry, the rules provided the basis for this skirmish that tested a light cavalry tactical design for 80 or more figures. Comments follow on the design and the rules, with a few concluding remarks.

Two cards decks, one for each side, controlled movement in the design. Each deck of 21 cards contained 18 action cards for the figures on that side, and 3 command cards. Alternating draws from the two card decks picked the figures that moved or acted on each turn. The number of cards per figure varied from 3 to 6. Cards randomized the figures that could take action; figures brought into action by a card draw began, and finished, combat on that draw. Other controls in the card decks will be described in the conclusions.

The rules rate skills from veterans (A) to novices (D). Figures drop one skill level for minor wounds, three levels for major wounds. Skill levels shift up or down for close combat weapons, mounted figures, double time fatigue, cover, prone and facing away positions. Morale will also shift the skill levels of the men involved.

The limited area of deployment attempted to simulate a scouting light cavalry party of Cossacks stumbling across an unknown outpost. The Cossack player viewed the terrain without French figures, then placed his unit of five Cossacks on the edge of the restricted deployment area. Only the visible French troops on the Cossack's line of sight were placed on the terrain; the rest were added as they would be observed in the action. The sandy rolling area north of the River Lusha was laid out on a floor, a soft blanket was thrown over various objects for gentle grades, model trees added, and the buildings drawn on small boxes by felt pen.

A few test moves familiarized the players with the rules. Four trials followed, each with different Cossack players. Cossack orders were to (1) reconnoiter and (2) harass the enemy. Orders tended to be forgotten in the immediate action at the buildings in spite of the inviting wide expanse of the terrain. No Cossack player took advantage of an off-terrain concealment by placing a Cossack or two and moving them off-board, or bringing on the other Cossacks, as their cards were drawn, into the developing situation. Random effects of the card moves, coupled with the era's inaccurate musket fire represented by the rules, insured that the limited area of initial Cossack deployment did not handicap the Cossack players.

Encirclement, natural in irregular Cossack tactics, appeared best in the second trial, and it completed the game design in the shortest time. In the description that follows, Cossack moves are labeled "C", French moves are marked as "F". The Cossack leader and village ataman, Afanasy (A), together with Bogdan (C class) and Koltso (C class), could see Sgt. Cangelosi, and Pvt. Peri, from their deployment on the edge of the terrain. The Cossacks moved first on each trial.

The Encounter

C1 . . . A card for Koltso is drawn; he charges Pvt.

Peri with a lowered lance. Both combatants go into action

on a single card draw in close combat distance. Morale

rolls occurred for 54mm combatants within 10 inches, and

after a wound. If afraid, the figures could not advance or

initiate close combat, but could defend themselves. The

design modified the rules to allow morale rallies, in spite

of the skirmish's short duration. If fear was registered by a

figure, it was allowed a morale rally on its next card draw.

Neither combatant, here, came out afraid, but they both

missed each other in the combat pass.

C1 . . . A card for Koltso is drawn; he charges Pvt.

Peri with a lowered lance. Both combatants go into action

on a single card draw in close combat distance. Morale

rolls occurred for 54mm combatants within 10 inches, and

after a wound. If afraid, the figures could not advance or

initiate close combat, but could defend themselves. The

design modified the rules to allow morale rallies, in spite

of the skirmish's short duration. If fear was registered by a

figure, it was allowed a morale rally on its next card draw.

Neither combatant, here, came out afraid, but they both

missed each other in the combat pass.

F1 . . . Pvt. Arditi's card comes up; he fires on, and kills, the Cossack Koltso.

C2 . . . Drawing a command card allows the Cossack leader Afanasy to take action; by voice and arm aignals he directs a double envelopment . . . Matvei (C class) and Yakov (C class) to their left, he and Bogdan to the right.

F2 . . . Another card for Pvt. Arditi, reloading frantically (a necessary five turns under the rules); he wounds himself on his fixed bayonet (a delightful hazard of the rules), and so he is delayed one turn in reloading. The design allowed a reloading action to proceed on each card draw.

C3 . . . A card for Afanasy, he gallops around to his right, sees Pvt. Arditi and charges him, but completes his move short of contact. Both combatants register unafraid in morale, hence neither one will turn aside. Both can initiate attacks now, that is, if Arditi can reload in time.

At this point the design's second part occurs. A party of six French horsemen move on to the terrain at Y (Sketch 1), grouped tightly together to simulate the poor visibility in the morning mist on October 25th. One Cossack player treated this with indifference, more intrigued with killing Prince Eugene's Italian troops. Another Cossack player, on his trial, showed a mild interest, reserving the French mounted party for a future move. Our immediate second trial player remembered his Cossack's first order was to reconnoiter.

F3 . . . Sgt. Cangelosi's card appears; he turns 45 degrees (up to 90 degrees on one turn is possible in the rules), fires on Afanasy, but he misses. Although each action could be a move, in a strict sense, they were allowed as one move.

C4 . . . A card for Afanasy; having seen the body of French horsemen to his right he turns 90 degrees, and gallops the full extent of his move, dropping his lance deliberately at the end (allowed by the design in horsed movements). Afanasy sees the six horsemen in open formation.

F4 . . . Pvt. Tutto (in the log chapel) fires on the Cossack Bogdan inflicting a minor wound. Bogdan falls from his horse; he can stand on the very next card draw, with a minor wound, however, he cannot initiate action should his card be drawn on this next turn. Bogdan comes out of his morale roll unafraid. The design put aside the roll provided in the original rules to prevent his horse from fleeing.

C5 ... Another card for Afanasy; he has identified the Emperor Napoleon in the French group (by a small sign hung around the tiny neck; if Afanasy can't read English, he has, at least, identified a high ranking French officer). Afanasy unslings his captured musketoon and aims; at this moment the shutter of time comes to a stop, as history may forever be changed. Afanasy fires, and misses. Napoleonic wargamers are saved, to continue adding to the thousands of tramping feet; history sweeps on in its expected course; as the less imaginative have it, in the only way history could happen, because that is the way it did happen.

F5 . . . Poor Arditi hit again: he is still unable to fire having

wounded himself once more on his bayonet, and having

suffered a misfire, another delay in the rules.

F5 . . . Poor Arditi hit again: he is still unable to fire having

wounded himself once more on his bayonet, and having

suffered a misfire, another delay in the rules.

C6 . . . A command card: the Cossack leader Afanasy observes the intact Napoleon and his party move off the terrain on the side road Z (Sketch 1), a turn by a

C6 . . . A command card: the Cossack leader Afanasy observes the intact Napoleon and his party move off the terrain on the side road Z (Sketch 1), a turn decided by a dice roll. Napoleon's party moves as a single entity on each card draw. Afanasy signals to break off action. The Cossack player confided that Afanasy's command resulted from the ataman's disappointment over his failure. With 40% casualties in his command he could do little else. Here, the design intruded on Afanasy's morale, and will be taken up in the conclusions.

F6 ... A French command card: Sgt. Cangelosi orders everyone into the blockhouse at the chapel (where they could also offer prayers of thanksgiving?). Action in the second trial ends.

No Cossack player knew about the October 25th 1812 incident where Napoleon, for a short time, was threatened by attacking Cossacks; -- for them the design was a historical surprise. One Cossack player intended to destroy the French outpost before turning to the mounted party, but it proved so difficult a fight he did not have time; in the interval, the French mounted party moved off the terrain. His confidence in the Cossack's ability to take on what might have been a body of French cavalry (the design's alternative for the experienced player, or one who knows about October 25th) was admirable, but misplaced. The Cossack figures seemed to exercise a captivating influence over the players.

The distance between the outpost and the French mounted party insured the Cossack player time for a decision, but shortened as the French party moved past point Z. Hostile contact became possible; if a command card was drawn Cossack attitudes could be coordinated. In any event, the design had the mounted party intent on retreating off the terrain.

Designer's Comments

Skirmishes open, and close, as single figure actions of a few seconds duration. In a tactical situation, these single figure actions must fit together to make a tactical unit function, and fulfill a tactical plan. When a card deck initiates action, the player must combine this random selection of his single figures to carry out the tactical plan. Building tactical units from single figures, and moving the figures as blocs, loses the unique personal quality of single figure skirmishes.

Using a card deck alters real and scale time in tactical actions based on single figure skirmishes. Simultaneous individual actions shift to become a series of tactical actions influencing each other. Inevitable distortions of time and actions occur from this shift. A designer solves this distortion by stressing the situation's playable qualities.

Card decks will reflect historic tactical practice, as they did the characteristics of irregular light cavalry, and regular infantry, in this skirmish. The Cossack leader Afanasy (A class) had 6 cards, the four other Cossacks (C class) had 3 each. in addition, Afanasy was able to issue commands by the 3 command cards. Once Afanasy was put out of action, no other Cossack had enough moves to establish a dominant line of action to coordinate the rest. The Cossacks, scattered out as irregular light cavalry, and leaderless, disintegrated into individual fighters.

In contrast, the French had Sgt. Congelosi (A class), Arditi (B class), Tutto (B class), each with 4 cards, with access to 3 command cards, and two soldiers (C class) with 3 cards each. Figures rated (A) or (B) under the rules were equal in combat effects. Using these figures in combination assured the French player the means of continuing actions to fulfill a defensive tactical plan, in spite of casualties. The French movement rate, as infantry, kept them close together, and this closeness enhanced the French coordination of fire. Cossack players added to their difficulties by fighting a tactical action at the outpost, instead of masking it, and carrying out their orders.

Overall, the rules were simple, workable, and the best of qualities: open to modification. The rules avoided the common fault of complexity striving to pass for realism. Heavy Napoleonic tactical casualties were reproduced, 40% to 60% suffered wounds, or were killed. Faithful to the era, individually aimed musket fire frequently missed its target, aided by the morale throws that could lower combat skill levels. Casualties limited the Cossacks severely. They were unhorsed, split by space and obstacles, unable to coordinate actions on line of sight. These disadvantages followed from the design's wide terrain, its few figures, and the Cossack tendency to be on exterior lines.

No easy solution exists for morale in skirmishes. Unless, of course, the simple movements of retreat or advance of most rules satisfies the complexities of morale in the design. Skirmish rules, as in this set, concentrate on f ire and maneuver outcomes rather than morale itself. Controlling more than one figure transposes an individual skirmish into one of tactical units, losing personal action. Most rules will then carry personality, morale, leadership, fire and maneuver as a single numerical total, or tactical unit combat rate. At best a compromise, it voids the individual personality and morale effects of the skirmish. Sequences of individual action contained in the tactical skirmish offers a continued opportunity for changes in individual morale. All battle action reflects the individual personality as the basis of morale and leadership; it has a direct influence on combined fire and maneuver.

Skirmish morale should originate in the personality of the single figure; rules must be unbearably complex to do this. Encouraging a player to freely develop his individual way of play could establish this as a single figure's personality. If so, in a tactical action, a commanding player will see his careful plan evaporate in the individual whimsy of his subordinate players, a representative and desirable feature in some tactical designs. Increasing single figures, assigned to individual players, must increase players; this has obvious practical limits.

The design experimented with a pack of personality factors, flipped on each card draw, that designated morale outcomes such as "figure develops a sudden caution on this move". These experimental elements were tried as part of the figure's action, but were not put into play. No consistent and simple way tied the items to the few simple personality traits assigned to each figure, except by an arbitrary decision, or multiple dice rolls. On one move (C6), a card indicating a morale change influenced the player to break off action. Role playing games suggest ways of improving on this crude design expedient.

Some players see skirmishes as very elementary games. Viewing battle as human experience makes of it what one sees, hears, and does. This is as true of the commanding officer as it is of the man in the ranks. A wargame establishes a role for the player. Will it be the common soldier, or the highest commanding officer's role? Skirmishers elect to play the common soldier. A single soldier's actions are direct, immediate, and personal. In contrast, a commanding officer issues orders, distant actions take place, and only the most optimistic see this action as a direct consequence of his orders. Role and realism in wargaming are a matter of personal taste. Optimism concerning the commanding officer's controlling role comes from grounding the wargame in military history . . . a very selected view of military reality. The common soldier's personal experience comes from an equally selective, and valid, view of military reality.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. V #2

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1984 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com