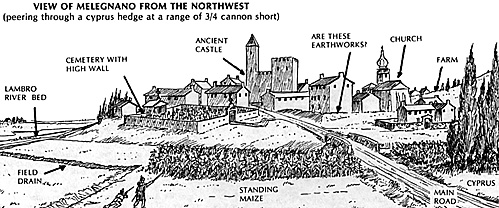

VIEW OF MELEGNANO FROM THE NORTHWEST (peering through a cyprus hedge at a range of 3/4 cannon short)

VIEW OF MELEGNANO FROM THE NORTHWEST (peering through a cyprus hedge at a range of 3/4 cannon short)

A campaign which has received much less attention than it deserves concerns the Franco-Piedmontese War against Austria in North Italy, 1859. Not only was this a crucial step in 'the making of Italy', but it also marked a significant turning-point in European tactical theory. This was the first war in which both sides possessed the riflemusket (even though the Austrians had fewer than they needed) and, because it was fought in Europe, it was more influential for European armies than the American Civil War, despite the fact that similar weaponry was deployed.

At first sight the Italian campaign has much in common with the American Civil War, since in both cases the battles were exceptionally bloody. At Solferino, each side admittedly lost less than ten per cent of the troops engaged in killed and wounded-not a particularly high proportion by Napoleonic standards-but when one considers the short duration of the action (little more than twelve hours) and the large size of the armies (around 180,000 men in each), one starts to get some inkling of the ferocity of the fighting. About 30,000 men were killed or wounded on that day alone, and the humanitarian reaction to this slaughter was so great that the International Red Cross was founded.

On closer examination, however, the military lessons drawn from the 1859 Italian campaign turn out to have been very different from those of the American Civil War. In the latter case the new weapons appear to have strengthened the power of the defensive. Battles became bogged down as each attack, no matter how energetically pushed, was beaten off.

In Italy, by contrast, it seemed to be the offensive which was vindicated. Time after time, the French successfully carried positions at the point of the bayonet, and crossed the dangerous beaten zone so fast that the defenders had no time to develop the maximum benefit from their fire. Perhaps this campaign did more than any other to keep alive the spirit of the bayonet in the European armies of the later nineteenth century.

A number of reasons can be adduced for the French success in 1859, not least of which is the short duration of the war. Unlike the Americans of the 1860s, the two armies were not engaged long enough for the best defensive tactics to be perfected, and after a couple of minor early set-backs the Austrians appear to have lost the morale battle to their opponents. The French were acknowledged to have the best army in Europe at this time, and their superiority in almost every department of the military art was swiftly asserted. Once they had realized the ascendency which they enjoyed, the balance of morale swung definitively in their favor.

The attacker in North Italy was also very greatly assisted by the terrain, since numerous orchards and high standing crops made it very difficult to find open fields of f ire. The long range weapons of the defense were frequently wasted, in these circumstances, unless the attacker could be kept at bay by buildings or walls.

One Zouave officer stated: "My opinion is that we were lucky at Magenta. The thick country in which we fought favored us in hiding our inferior number from the Austrians. I do not believe we would have succeeded so well in open country." (Quoted from Ardant du Picq's 'Battle Studies', translated 1921, p.269.)

The theatre of war, of course, was the same as that in which the First Napoleon had made his name, and it was perhaps no accident that his lesser nephew tried to model his tactics upon Napoleonic methods. Skirmish clouds and Close columns were the main infantry formations, although the line was also used.

The campaign was also interesting for the effect which it had on the thinking of Colonel Ardant du Picq, the best writer on infantry tactics in the nineteenth century. Ardant was interested in the way in which units could lose their cohesion and order when under f ire, and the way in which the neat geometrical formations assumed by Most military historians were a very far cry from the sort of desperate improvisations which really took place on the battlefield.

The 55th infantry regiment at Solferino gave Ardant a perfect example to support his thesis: "The regiment was then put on the road, marched some yards and formed in battalion masses on the right of the line of battle. This movement was executed very regularly although bullets commenced to find us. Arms were rested, and we stayed there, exposed to fire, without doing anything, not even sending out a skirmisher. For that matter, during the whole campaign, it seemed to me that the skirmisher regulations might never have existed.

"Then up came a Major of Engineers, from General Niel, to get a battalion from the regiment. The 3rd battalion being on the left received the order to march. The major commanding ordered 'by the left flank', and we marched by the flank, in close column, in the face of the enemy, up to Casa-Nova Farm, I believe, where General Niel was.

"The battalion halted a moment, faced to the front, and closed a little.

"'Stay here', said General Niel; 'you are my only reserve!'

"Then the general, glancing in front of the farm, said to the major, after one or two minutes, 'Major, fix bayonets, sound the charge, and forward!'

This last movement was still properly executed at the start, and for about one hundred yards of advance.

"Shrapnel annoyed the battalion, and the men shoulder( arms to march better.

"At about one hundred yards from the farm, the cry 'Packs Down' came from I do not know where. The cry was instantly repeated in the battalion. Packs were thrown down, anywhere, and with wild yells the advance renewed, in the wildest disorder.

"From that moment, and for the rest of the day, the 31 battalion as a unit disappeared." ('Battle Studies' pp.27 271)

We do not know whether the attack by 3/55 was successful or not, but it is clear that it was conducted as "soldier's battle" hardly less confused than the celebrated fighting at Inkermann in the Crimea a few yea earlier. Ardant du Picq, in fact, suggests that this is a true "face of battle" in almost every age.

What we do know about the 3/55 is that their 3rd companies had started with a nominal strength of around 132-13 Twenty of these were observed to have sat out the battle some distance in rear, "lying in the grass while the comrades fought". Forty- seven men were present at a recall towards the end of the day, having stayed sufficient close to the battalion's central core to be within effective "rallying range". In practical terms, in other words, the company had lost no less than 55 per cent of its soldiers during the battle.

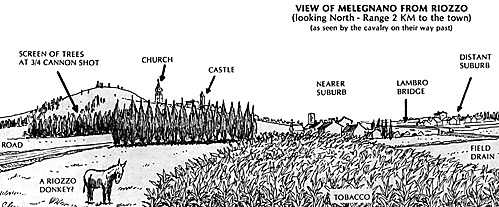

VIEW OF MELEGNANO FROM RIOZZO (looking North - Range 2 KM to the town) (as seen by the cavalry on their way past)

VIEW OF MELEGNANO FROM RIOZZO (looking North - Range 2 KM to the town) (as seen by the cavalry on their way past)

Yet by the next morning, about 94 men were back with the company, representing approximate 70 per cent of the nominal strength. At least 25 percent in other words, had been skulkers or "combat refusals' only 30 per cent represented permanent casualties to the company-killed, wounded, prisoner or run away forever to "la dolce vita" of the Po Valley. Quite how this remaining 30 per cent was distributed we will never know. The crucial point to notice, however, is that at least 25 percent of the company's strength took the decision that the battle was not for them, and therefore stayed out of it. And this was on the victorious side of the combat; the effectiveness of the Austrians must have been considerably lower.

Such speculations, however, do not appear to be generally pursued by the majority of military historians, who prefer to portray every soldier as a hero and as a well-planned movement of devoted troops.

I hope that I have by now indicated some of the fascination which this extraordinary campaign should hold for the military hobbyist. It stands as a European equivalent to the American Civil War--but so very different in its implications. As it happens, I also have a personal and emotional attachment to this war, having long been under every battle the spell of Louis Napoleon "le petit", and having been mightily moved on one of my very earliest battlefield visits by the sight of a broken child's doll on a rubbish heap beneath the tower of Solferino. However that may be, the point of this story is that earlier this year I decided to make a wargame of the campaign, and I have now found that it has developed into a most gripping and illuminating exercise.

It all started in a correspondence with Ned Zuparko, well known to readers of THE COURIER, who mentioned that he would like to take part in a "Wargame Developments" (WD) game. Since he lives in California and WD is based in England, this would necessarily have to be a postal game. The postal format is, in any case, well suited to a careful and detailed study of any particular battle, and so I seized the chance to launch a postal role-playing game based upon Baraguey d'Hilliers' French I Corps on the fatal day of 8th June 1859, at Melegnano.

I Corps saw as much action, in the campaign as a whole, as any French formation. It also contained some of the best-known officers of the day: Bazaine, Forey and de Ladmirault each had a division in this outfit.

The aim was, therefore, to give each player one of these divisions, present him with the situation as he would perceive it at various phases of the battle of Melegnano, and see what he made of it all. Melegnano was a real action, fought mostly in a thunderstorm (hence exceptionally favorable to the bayonet), but which displayed the high "butcher's bill" which was characteristic of the campaign. Out of a nominal 23,000 men engaged on the French side (of which probably little more than half can have been in the front line) almost 1,000 were killed or wounded within the hour that the battle lasted. Several military commentators have pointed out that the combat need not have taken place at all, since the Austrian brigade holding the town was a rearguard and could have been maneuvered out of its positions. Baraguey, however, determined upon a straightforward frontal assault which did succeed in its aim -- but only at a cost in lives which is comparable to the entire British loss in the recent Falklands operation.

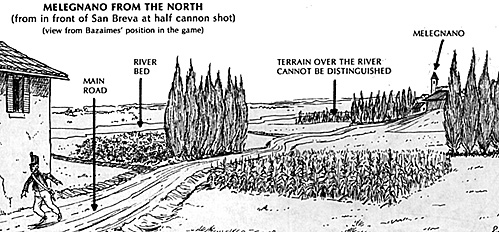

MELEGNANO FROM THE NORTH (from in front of San Breva at half cannon shot)(view from Bazaimes' position in the game)

MELEGNANO FROM THE NORTH (from in front of San Breva at half cannon shot)(view from Bazaimes' position in the game)

As umpire, I sent each player a description of his position at 3:30 pm, some hours before the battle actually started. In some cases these details were supported by sketches, drawn from imagination, of what the players could see (in fact the imagination was a little wild at some points, since a quite unhistorical hill soon started to loom over theactually very flat-town of Melegnano). Copies of correspondence received, and impressions of the characters of colleagues and subordinates, completed the briefing.

Each player was supposed to play according to an historical character sketch which was also supplied. Thus Ned, as Bazaine, was told that he was a cheery, outgoing officer who was popular with his men but liable to be paralyzed by indecision if confronted by any problem of more than marginal complexity. An important aim for him was to save his soldiers from unnecessary losses, and make their lives easier. He was also told that he had never heard of either Mexico or Metz, which were both important milestones in the career of the real Bazaine!

The turns varied in the length of time represented, but the average turned out to be about three quarters of an hour. in each one the players sent in details of what they wanted their characterto do: to whom he would talk, and how (including details of 'body language' to be used), what letters were to be written, and so forth. Thus in the early turns, the players nearest to Melegnano had to sort out a plan of attack and then gradually, and the pace hotted up, they would have to modify it in accordance with the the Corps commander's wishes, and put it into execution.

In fact all the divisional commanders somehow assumed that when the Corps commander had called for an attack that evening, he actually meant to attack on the following morning. He, therefore, had to go round and get them moving, in a series of abrasive interviews. in the end he never did find the cavalry division, since its commander (played by Ned Zuparko's brother Bob) had been briefed to avoid any fighting, and behave like a "Flashman" figure.

Bob therefore pressed his reconnaissance as far and as fast as he could in the opposite direction from th, battle, and when he came to a town which had recend, been evacuated by the enemy, he reported that he hai cleared it with cold steel.

ORDER OF BATTLE OF BARAGUEY D'HILLIERS

I CORPS

AT MELEGNANO

Corps HQ

1st lnf Div

Forey

13 Battalions

12

Guns

2nd Inf Div

de Ladmirault

13 Battalions

12 Guns

3rd lnf

Div

Bazalne

15 Battalions

12 Guns

Cav Div

Desvaux

16

Squadrons

6 Guns

Corps Artillery

Corps Train

In the game, as in the real battle, the two leading infantry divisions were thrown over-hastily into the assault, with bad conditions of visibility and with little idea of what was before them. Actually they enjoyed a great numerical advantage over the enemy, but they had to tackle some strong fieldworks, including a battery earthworks and a banquetted cemetery wall. As in the real thing, therefore losses were high. Although the results of each attack in the game were decided by die rolls, the overall shape of the action was fairly true to life. It was not entirely "fiction", but neither was it entirely "fact". It occupied thi middle ground between the two which has sometime been labelled "faction", and which tends to be used to, little by the wargamer.

A great attraction of this game was that the players did not look down on the battle, as is usual in table top games, as if they were in some balloon tethered over the battlefield. Their fields of vision were appropriately narrow, and the information available to them was realistically limited. On the other hand, the scope of their problems were wider than is normal in tabletop games, since they had to think of more factors than merely the movements of their battalions.

They had personality profiles to live up to, as well as a wide range of other characters to react with (both played and non-played characters). The scene was described to them in terms reminiscent to Ardant du Picq's account of Solferino, quoted above, with the difference that, at each stage, they could intervene in the action as participants in the drama. To put it another way, the battle was portrayed by a word picture and blackand-white sketches, instead of the dioramas of miniature figurines which are the normal form of presentation in table-top games.

SOURCES

This war is described better in the French literature than in English, but an interesting recent tactical discussion is in Steven Ross' "From Flintlock to Rifle, Infantry Tactics 1740- 1866" (Rutherford-MadisonTeaneck- Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Cranbury NJ 08512, 1979). A straightforward general account is H.C. Wylly's "The Campaign of Magenta and Solferino" (Swan Sonnenschein, London 1907), and Major Miller's 11 A Study of the Italian Campaign in 1859" (Royal Artillery Institution, Woolwich, 1860). There is certainly much scope for a clear modern military account of the campaign!

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. V #1

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1984 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com