The main source for this article is the Saxon cavalry regulations of 1810. I intend to quote from them as often as possible indicating the page number in brackets afterwards. There are no diagrams in these regulations so I hope that mine will serve to clarify the text. My source for the Prussians is the German General Staff's work which will also be mentioned.

The cavalry of this era were divided into the light and heavy branches. There was however only one set of regulations to which they were all trained, which included flanking, skirmish attacks, picket duty, reconnaissance, in short, all the tasks of the war of outposts.

However they did specialize according to their specific duties. The heavy cavalry, riding boot to boot in closed formations were used almost exclusively as battle cavalry. The light cavalry too could be used as battle cavalry, but as the heavies tended not to be armed with the carbine, their use in a skirmish function was limited.

The Saxon regulations make that very point: "The cuirassiers are the primary arm of the cavalry. The big, strong man, protected against wounds by the cuirass, must be more effective with his stabbing sword than the smaller and unprotected light cavalryman. The stronger German horse whose gallop for the necessary distance for impact is faster and more forceful, especially suitable for riding down the enemy and breaking him." (Pp. 2)

And what do the regulations have to say about light cavalry? "The indispensibility of the light cavalry is most clearly to be seen in pressing forward in loose order or in skirmisher attacks on the enemy infantry, causing them to let off their fire before the closed attack, by surprising the enemy with strategic diversions either offensively or in covering our withdrawal, by pursuing the retreating enemy for days at a time, confusing him, causing him to deploy, to halt, where it is often necessary to trot for hours at a time and to cover 8-10 (German) miles in a short time.

Furthermore, picket duty and the war of outposts is the duty of the hussars and the light horse; ... foreign horses, such as Russian, Polish and very light German, which are more consistent with running and can endure greater hardship even when poorly fed; the saddle and remaining equipment of the horsearmament, clothing of the cavalryman - everything suits these troops primarily to the mentioned service." (Pp. 5-6)

Cavalry skirmishers had many tasks. They reconnoitered on the advance, scouting outthe terrain, trying to cause the enemy to fire and facilitating the shock of their own formed cavalry standing behind them, throwing the enemy into confusion, constituting part of the skirmisher attack, etc., etc. Cavalry skirmishers also showed the enemy that he now had to reckon with a serious attack and should immediately take counter measures.

An often unknown point is that both cavalry and infantry skirmishers operated together, supporting each other. That is how a withdrawal could be covered or an attack hidden and prepared.

What does "skirmishing" mean, what sort of fighting does it involve? "Skirmishing is fighting by individuals, it is carried out either by the cavalry operating alone or by cavalry and infantry operating together." (Pp. 186) "For skirmishing, two things above all are necessary. Firstly, that the soldier is master of his horse and secondly that he is fully aware of how to use his firearm."

Skirmishing was often carried out in a very loose order and wargamers tend to use their figures much too close together. The soldier was left to his own devices, making his own decisions. The text following will illustrate how high the demands of both horse and man were. All other tactical aspects of the Napoleonic era were distinguished by the total control of the officer. indeed, the better the control and supervision, the more effectively the soldiers could be led.

"Instruction for Skirmishing in the Open."

(Certainly similar to that in battle, however adapted to

the tactical situation. Also to be noted is the omission of any

characteristic regulation 'frippery' as everything was to be

done naturally - HKW)

(Certainly similar to that in battle, however adapted to

the tactical situation. Also to be noted is the omission of any

characteristic regulation 'frippery' as everything was to be

done naturally - HKW)

"a. The carbine is raised, hooked on and carried in the right hand above the lock with the butt resting on the right thigh. This is done without any orders." (See drawing 1)

"b. when ordered, fire the carbine in the direction of the enemy over the horse's head (taking care not to frighten it! - HKW)

"c. When ordered, aim to the left and fire, which is only allowed when the horse is in motion because if its side is turned towards the enemy, the whole length of the horse is offered as a target and if standing still, aiming and hitting by the enemy is facilitated. It should not be necessary to be reminded that aiming to the right is not possible as this goes against the natural build of the body." (Pp. 186/187) (see drawing 2).

When aiming to the left, the butt of the carbine is of course

pressed against the right shoulder. Theoretically, firing is

done standing over the top of the head of the horse, that is

close to its ears. That is why firing was surely always done to

the left so that the cavalryman was at an angle to the enemy.

At such an angle, with the horse moving, the number of hits,

already not very impressive, must have been reduced to next

to nothing. If aiming was only slightly to the left, then the

cavalryman should have been able to keep his horse quiet.

When aiming to the left, the butt of the carbine is of course

pressed against the right shoulder. Theoretically, firing is

done standing over the top of the head of the horse, that is

close to its ears. That is why firing was surely always done to

the left so that the cavalryman was at an angle to the enemy.

At such an angle, with the horse moving, the number of hits,

already not very impressive, must have been reduced to next

to nothing. If aiming was only slightly to the left, then the

cavalryman should have been able to keep his horse quiet.

To facilitate the loading process, the cartridge box was pushed to the front. The Prussians fixed the ramrod either to the carriage box or the crossbelt with a chain so that it could not be dropped. The British went so far as to fix it on the carbine itself.

Despite that, cavalry skirmishers came only as close as 80-120 paces from the enemy so the number of hits must have been minimal indeed. It was more important to the Saxons to prevent themselves from being shot at. The Prussians mostly fired one-handed. Cavalry skirmishers thus did not have the task of inflicting losses on the enemy by prolonged skirmishing, so their actual functions have been listed. They were also an effective measure against enemy infantry skirmishers.

"Soon the Prussian infantry appeared, skirmishers to the fore and fired at the Polish cavalry. Deminski then took the initiative again and shouted at the lancers: 'Volunteers for skirmishing!' and soon thereafter, the infantry were driven back by the lancers." (From - Mosbach: Deutsch- Franzoesische Kriegsgeschichte 1800-1813, pp. 247)

"d. After the carbine has been fired, the soldier is to gallop towards the enemy and attack him with his sabre, drawn only after having fired the gun, using the customary method which is made clear to the recruit, that he is never to offer the enemy his left side, rather that he should seek to gain that side." (Pp. 187) It is clear that if the infantryman stands to the left, then the cavalryman would find it difficult to use his sabre, both for attack and defense.

Of course, in action, an attack is not made after every shot, rather, the tactical situation and the skirmisher's orders determine the next move. An attack is especially good when fighting infantry skirmishers or if one wants to weaken a closed formation by, say drawing their fire so that one's own formed cavalry can get in without being shot at. Or an attack on the skirmish line is first provoked, then the line is pulled back so that the enemy can be driven off by one's own formed troops. It must have been very uncomfortable for troops to be continuously tormented by skirmishers without being able to take effective countermeasures. The ideal combination is mixed skirmishing by both cavalry and infantry.

"e. Should the soldier be forced to retire on his own troops, he is to be instructed to let his sabre go (it is hung on the wrist, held by the sword-knot - HKW) and to draw his pistol and fire a shot to the rear with it so as to prevent the enemy from pursuing." (Pp. 187)

"It is clear from this that the carbine is the weapon of the attack and the pistol that of the defense and at the most can only be used as an offensive weapon in a melee and that is why it should be especially impressed on the soldier that only in an emergency should both pistols be fired off and that rather he should reserve one shot." (Pp. 187) Not that the pistol was also used on picket duty in preference to the carbine. Pickets were required to indicate the presence of the enemy by making noise.

"General Instruction on Skirmishers"

"No more than one quarter of the men should be used as

skirmishers and they should be split into two groups, one of

skirmishers, one as a reserve. A squadron should therefore

skirmish with one platoon (in the Saxon cavalry, 4 platoons =

1 squadron - HKW), a regiment using one platoon from each

squadron. When reserves are present, they are used as

such.

"No more than one quarter of the men should be used as

skirmishers and they should be split into two groups, one of

skirmishers, one as a reserve. A squadron should therefore

skirmish with one platoon (in the Saxon cavalry, 4 platoons =

1 squadron - HKW), a regiment using one platoon from each

squadron. When reserves are present, they are used as

such.

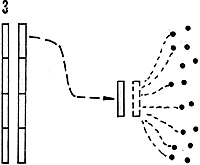

This platoon gallops to the front and stays at a reasonable distance according to the terrain, about 150 to 300 paces in front of the centre of the squadron. The front rank draws carbines and both ranks are organized into No. i's and No. 2's; once this has happened, all No. i's of the front rank gallop forward forming a line to the left and right, covering the squadron, the No. 2's (of the front rank - HKW) follow to a distance of 50 paces and forms such a second line that every No. 2 acts as a second to his No. 1. The second rank remains standing in reserve with drawn sabres and replaces or relieves the No. 1 and No. 2 of the front rank according to circumstances." (Pp. 188-189) (See drawing 3).

The skirmishers should move far enough away from each other so as not to place each other in danger. Only a quarter of the unit was used so that enough men remained ready for the charge. Skirmishing is therefore a combination of both open and closed order troops.

A drawing is included to show how the sabre was held'in reserve'. Many wargames figures are made holding it freely in the hand which may be fine for individual officers, but in close order it would be suicide. The regulations describe how it should be carried.

"The hilt is to be pressed between the navel and the hip

and carried low but without putting it on the hip. The cutting

edge is to point inwards, the blunt edge along the sleeve

seam on the shoulder. The elbow must be held firmly." (Pp.

54) (See drawing 4).

"The hilt is to be pressed between the navel and the hip

and carried low but without putting it on the hip. The cutting

edge is to point inwards, the blunt edge along the sleeve

seam on the shoulder. The elbow must be held firmly." (Pp.

54) (See drawing 4).

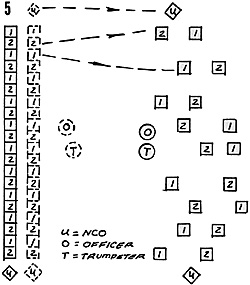

"Once skirmishing is to begin, the horse is to turn to the right (as a sign that everything is ready - HKW), remaining in line and then turning left again so that every thing moves in alignment (offering a poor target and covering one's own troops - HKW). If No. 1 has charged the enemy after having fired his carbine, then No. 2 moves up to the first line and holds his carbine at the ready, supporting the No. 1 as he retires; No. 1 falls back to the second line, loads his gun, does not lose sight of No. 2 so as to support him likewise and relieve him in the first line." (Pp. 189) Taking a platoon at around 40 men, 20 are in reserve and from the remaining 20, 10 are in the first firing line. But not all of themfire at once, rather about four do so that a continuous fire can be maintained. From the skirmish line, one can easily go over to the "skirmish attack". (See drawing 5).

From the above one can determine that:

From the above one can determine that:

- 1. The first line of skirmishers is continuously supported

by a second line of seconds and both are again supported by

the second rank of reserves.

2. The skirmishers must take care that not all of them fire in one go so that a consistent fire can be maintained.

3. The officer with the trumpeter places himself between the reserve of the second rank and the line of seconds (1st rank) in order to control the direction of the flankers as well as bringing forward reserves when needed.

Due to the lack of space, it is difficult to show the true extent of the dispersal of the skirmishers. Of course, the officer and trumpeter did not remain on one spot, but instead rode down the line. He would probably be a good deal nearer to the skirmish line than the reserve. Any possible change in the situation would require orders which were conveyed by trumpet signals as the skirmishers were widely dispersed.

"f. Finally, the men must know the trumpet signals exactly and be used to following them immediately and without hesitation as it is often important to stop skirmishing quickly." (Pp. 189-190).

"On Cavalry Skirmishing when mixed with Infantry"

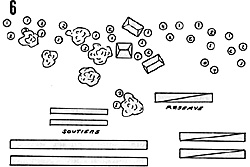

"This is the most effective form of the war of Outposts, and usually all major actions begin with it.

"in level terrain it is the honor of the cavalry to support the infantry with determination, whereas in broken and wooded terrain, it is likewise the duty of the infantry to support the cavalry.

"In open country, the skirmishers of both weapons are to be mixed and individual infantry skirmishers are to see out and use ravines, ditches and other such obstacles so as to receive and cut off any enemy flushed out by the cavalry.

"in mountainous terrain where the skirmishers consist almost entirely of infantry, the cavalry are to try to use all clear and level places to form themselves 'en masse' as a reserve either to support the retiring infantry or to fall upon the beaten enemy.

"if it seems that one is being forced to withdraw in open country, then the cavalry must do everything to cover the retreat, partly by increasing the number of skirmishers and partly by uniting the reserves for the occasional shock action 'en masse'." (Pp. 190-191).

The map will hopefully serve to illustrate.

The map will hopefully serve to illustrate.

"The corporals are positioned on the platoon's flanks, with 8 corporals being found in the front rank (1 squadron = 4 platoons x 2 = 8 corporals - HKW). The remaining four corporals remain in the second rank on the flanks of the half squadrons." (Pp. 124). The sergeants were not placed in the ranks but rather behind them. Whenever one went forward with the ranks, he would probably have stayed with the reserves. The corporals probably did not take part in the skirmishing, remaining on the relevant flank of the skirmish line.

Other nations would no doubt have skirmished in a similar fashion, each with their minor idiosyncracies. The Prussians had theirs and they shall be mentioned briefly using the renowned General Staff history of the Prussian Army of the Wars of Liberation as my source.

First, to the question of armament. There was a complete lack of uniformity of the patterns of weapons carried. Moreover, only the hussars were entirely armed with carbines. Along with the volunteers, the hussars were the only cavalrymen to wear both the carbine belt and the cartridge box belt. Other troops had their carbine hooks fixed onto the cartridge box belt and possibly only the trained skirmishers had this hook. in the cuirassiers and dragoons, twenty men per squadron were armed with carbines, and, if possible, twelve of them with rifled weapons.

Hussars too were to have this number of riflemen. 48 men plus 12 rifle-men per squadron were trained to skirmish. Those men also received the quietest horses so that they could operate the most effectively. All cavalry troopers were issued with two pistols even though in the summer of 1813 one of each brace was given to the militia cavalrymen because there were not enough to go around.

The pistol was 45cm long, the 'long' carbine 98cm, the 'short' smoothbore carbine 90cm and the rifle 81cm. The 'long' carbine, being longer and heavier had to be fired with both hands and was unpopular as mounted men obviously prefered using only one hand. it was used mainly by the cuirassiers. However, the skirmishers of the cuirassiers, dragoons and uhlans used the pistol, and the riflemen no doubt rifles when these were available.

However, it was the hussars and volunteers that were the proper skirmishers. All the hussars should have had the 'short' smoothbore carbine (other than the riflemen of course). It was fired with the right hand alone, but the use of both hands was allowed for"aimed" fire. As the riflemen were supposed to hit their target, they naturally used both hands. The men armed with the smoothbores covered the riflemen who were even allowed to dismount and fire. More than that, if he had a quiet horse, he was allowed to rest his weapon on the saddle.

It would seem that as pistols had a shorter range than carbines, the Prussian cavalry skirmishers were at a disadvantage. Of course, the number of hits made by such weapons was bordering on the negligible, but it must have been an uncomfortable feeling to be under enemy fire and not able to return it. Pistols were virtually useless in close combat and swords were more effective. The latter tended to be attached to the wrist by a strap when firing.

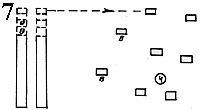

In the Prussian army, like the Saxon, it was the 4th platoon that had te responsibility to skirmish and the squadron's skirmishers were put into it. The 4th platoon rode 150-200 paces to the front and the four left flank files - 2 rifemen and 6 carbineers - rode a further hundred paces on. The carbineers formed the skirmish line and the riflemen were placed 20-30 paces behind them in support, firing alternately. The skirmish line was in continuous motion. A corporal controlled the fire whilst the officer controlled the use of reserves. The front line came to a stand at about 80-100 paces from the enemy. The six riflemen of the 4th platoon rode in the second rank.

The remainder were divided equally between the other

three platoons. When required, more men could be sent

forward to skirmish and support the six riflemen.

The remainder were divided equally between the other

three platoons. When required, more men could be sent

forward to skirmish and support the six riflemen.

A quote from an eye-witness, Freiherr Hermann von Gaffron-Kunern, an officer in a Silesian cavalry regiment at the Battle of Montmirailor Vauchamp (14th February 1814) will serve to illustrate my point:

"... we formed up somewhat to the rear, the entire enemy mass of cavalry at a short distance behind gentle slopes opposite us. Our task was to cover the right flank of our position and to maintain this position for as long as possible.

At first, as usual, the 4th platoon was sent forward to skirmish, but the enemy increased the number of his skirmishers so much that ours were too few and the 2nd platoon of every squadron was sent forward as re- enforcements. Half the regiment was deployed as skirmishers. I went forward with my 2nd platoon.

Our task was no easy one - our opponents, chasseurs and dragoons, fired at us with carbines which carried far, and during their later advance even sent bullets into the regiment, although without inflicting casualties. We only had a few carbines in the left flank files. Several of our skirmishers were wounded or killed..."

Similar accounts can be read of the great cavalry action at Liebertwolkwitz in October 1813. Large scale skirmishes occured whilst the cavalry reformed. Here too the French dragoons were respected because of their long carbines and the skills they had picked up in Spain.

Skirmishing cavalry in the Prussian army thus had a multitude of duties ranging from reconnaissance to large scale actions. Skirmishing with pistols was no doubt done only when the carbine-armed troopers were too few to carry out the task. As cuirassiers too were used for skirmishing, the border between light and heavy cavalry was blurred.

To prevent misunderstandings, I would finally like to point out that it was not the task of skirmishers to inflict enormous casualties on the enemy as his weapons were inadequate for that purpose. Rather, he was to cause the enemy discomfort, scout out the terrain, mask attacks, cover advances and much more. Although I have concentrated on the end part of the Napoleonic Wars, skirmishing was much the same for the whole of this period.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. IV #4

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1983 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com