Wargamers constantly strive to make their games more realistic by incorporating historical

details and their effects into their rules. Up to now, unfortunately, no Napoleonic set of rules can claim to be realistic, since they have never successfully dealt with Napoleon's dice in their rules. Though some designers have made modest attempts (note especially George

Jeffrey's, "variable-pip dice"), most have considered it a problem without a solution and

have therefore ignored it. In this article I'll give some background on the subject and some

suggestions to guide future Napoleonic rulesmiths.

Wargamers constantly strive to make their games more realistic by incorporating historical

details and their effects into their rules. Up to now, unfortunately, no Napoleonic set of rules can claim to be realistic, since they have never successfully dealt with Napoleon's dice in their rules. Though some designers have made modest attempts (note especially George

Jeffrey's, "variable-pip dice"), most have considered it a problem without a solution and

have therefore ignored it. In this article I'll give some background on the subject and some

suggestions to guide future Napoleonic rulesmiths.

After Napoleon's exile to St. Helena, a conscious attempt was made to downplay the Emperor's use of dice in battles and to instead portray him as a military genius. This tendency was especially strong, naturally, among the French school of historiography, notably in recent years by Commandant LaChouque in his "Anatomy of Luck". However, with the appearance of works by Professor David G. Duffy and Dr. Paddy Rothenberg, today we can safely say that such theories have been conclusively disproved. Among their discoveries was the fact that when Napoleon III issued the massive Correspondence de Napoleon 1er in the 1850's, all references to dice were deleted, though they were to be found in the Vincennes archives from which the Correspondence was compiled.

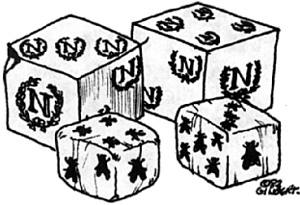

As a general, and later, as First Consul, Napoleon was forced to use whatever dice came to hand or were sent from Paris. However, once he became Emperor in 1804, he commissioned two sets; one the ceremonial set, usually reserved for state functions or diplomatic decisions (this was the pair he was holding in his shirt in the famous portrait by David), and the second pair as his campaigning dice, or, as he called them, his "battle dice". The ceremonial dice had pips in the form of the imperial "N" for Napoleon, while the battle dice ised "imperial bees" (the symbol of the Bonaparte family) as pips.

Battle Dice

The battle dice were not as well-crafted as the ceremonial dice, consisting of an inferior grade of ivory. This probably explains the unbalanced feel when held in the palm of the hand reported by contemporary observers, in the words of Berthier "a unique distribution of weight." Though smaller than the ceremonial dice, the campaign dice were heavier by an appreciable amount, probably to enable them to stand up to the rigorous conditions in the field. Napoleon's ability, whether in melee, weather or reinforcement rolls, to consistently roll one seven or eleven after another amazed his retinue and enraged his opponents. Talleyrand wrote that "we marvel at his prowess, which we can only ascribe to his lucky star. No other military man in Europe can compare".

Napoleon used his battle dice in almost every major engagement. In 1809, at Aspern-Essling, he experimented with the Habsburg "Kriegdicen", captured in Vienna a few weeks before, but dissatisfied with them, he went back to his own a short time later. His opponents were aware of this and at Tilsit Tsar Alexander presented Napoleon with a Russian set, but they were never used. In 1814, while negotiating with the Allies, Caulincourt offered to accept "natural frontiers, and no dice" as a part of a peace treaty, but the AlIies refused, guessing (wrongly, it turned out) that the dice had been lost on the Lindenau bridge at the Battle of Leipzig the previous year.

In 1815, when Napoleon returned from Elbe, Louis XVIII fled Paris, carrying Napoleon's battle dice with him to Ghent, later giving them to Wellington in early June. Napoleon was forced, therefore, to use his ceremonial dice for the Waterloo campaign. (One of these dice has a corner chipped off, the damage being done when Napoleon hurled them against the wall of his headquarters at La Belle Alliance shortly after the repulse of the attack of the Imperial Guard, and before he boarded his carriage to retreat from the field.)

Historians have often commented on Napoleon's great gamble at Waterloo, where he "staked everything on one throw of the dice", without realizing that he was using his ceremonial set. In the morning Napoleon was heard to say the chances were 90-10 in his favor "anything but a 2 or 4"; and even after the Prussians appeared he told Soult that the odds were still "60-40 in our favor. AW or better will do it." It is likely that if the Emperor still had his battle set, the outcome of this battle may well have been different.

To simulate this in our Napoleonic wargames, we should take into account more than just the better luck of Napoleon's dice, which can be easily done by applying positive modifiers to any such dice rolls when done by the Emperor. We must first of all determine before the game which set is present, and whether or not the dice roll is being used on the battlefield or in connection with a diplomatic or ceremonial function. We must also determine the proximity of Napoleon's carriage, since that is where the dice were kept when not in use; thus any last minute or unplanned movements on horseback away from his battlefield HQ might separate him from the dice, though usually this did not happen. With such considerations, any Napoleonic wargame will be able to better simulate history, and provide an exciting and fun-filled game.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. IV #4

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1983 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com