ED NOTE: This article was originally much broader in scope, and presented carefully reasoned historiographical information that emphasised previously underl/unutilized Arabic source materials.)

HISTORIOGRAPHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The importance of the battle of Al-Babayn had long been recognized by historians of the Crusades. This battle has served as an example of a battle-narrative for this period, though most western accounts suffer from some basic historiographical flaws:

-

1. Most western military historians rely too heavily on

Latin and Greek sources for their analyses of

Muslim military systems. They repeat gross distortions of

numbers, tactics, equipment, etc.

2. Most Muslim sources cited are translations and often use abridged paraphrases of the Arabic originals. This source limitation makes it impossible to gain a correct understanding of Arabic technical military terms, especially when the translator is unfamiliar or unconcerned with military matters.

3.Available translations usually focus on those sections of Arabic chronicles that deal directly with the Crusaders. This omission leaves many accounts of warfare among Muslims untranslated and unused, and these tracts are invaluable in gaining an understanding of Muslim military systems.

4. Finally, there is an almost complete avoidance of important Muslim military manuals, similar in style and substance to contemporary and more well known Byzantine manuals.

R.C. Smail, whose book Crusading Warfare: 1097- 1197, is considered to be the best compilation on this topic, did not cite important Arabic military treastises on Saladin's army even though they had been translated into French a decade before his book was published.

"The Battle of Al-Babayn" represents a detailed examination and application of Arabic sources that add crucial information to the narrative of this battle. The sources attached at the end of this article should be referred to in more depth to appreciate this reevaluation.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Fatamid Caliphate of Egypt was in a state of political chaos in the middle of the 12th century. A young boy, A[-Adid, sat on the throne, though he only actually ruled the huge palace complex in Cairo. Only the strongest survived outside of the palace where guile and exploitation of the weak was the rule. The Christian Franks and the Syrian Muslims both cast greedy eyes on the unprotected wealth of the valley of the Nile.

In January 1167, Sultan Nur ad-Din of Syria dispatched his ablest Amir, Shirkuh, to lead a picked expeditionary force to instigate a rebellion against Fatamid Egypt. Spies informed the Fatimid Grand Vizier Shaar of the Syrian advance, and he sent a message to Almaric, King of Jerusalem, asking for support against the Syrians. Almaric accepted this request and soon marched at the head of his army into Egypt.

Shirkuh eluded the numerically superior FrancoEgyptian army for nearly two months and eventually fled into upper Egypt. The Franco-Egyptians left a portion of their army behind in northern Egypt and set off in pursuit of Shirkuh. They soon discovered that their infantry could not keep up the pace in pursuit of Shirkuh's allcavalry force, and they were left behind as well.

A swift cavalry race ensued up the Nile until the Allies finally caught up to the Syrians near the city of Ashmunayn in central Egypt at a site called Al-Babayn (the two gates). The next day, Shirkuh marshaled his forces for battle and urged them on the words, "Each man (must) choose for himself a place to die!"

THE OPPOSING ARMIES

Author's Note: The capital letters in parenthesis, for example (WT), refer to the source that establishes the point discussed. See the bibliography for full references.

The order of battle is organized according to the WRG system for those wargamers who wish to refight this engagement.

The Syrians: William of Tyre estimated the Syrian force to consist of 9,000 mounted Tuks wearing mail and helmets, 3,000 light horse archers, and 10-11,000 Bedouins fighting with lances. Reliable Muslim souces indicate that Shirkuh's expeditionary force amounted to 2,000 picked cavalrymen ([A). William of Tyre's estimate is useful for illustrating the proportions in Shirkuh's force. Aside from the Bedouins, who were recruited in Egypt, (MQ), William's estimate allows 3/4 of Shirkuh's force to be mailed troops and 1/4 to be light horse archers.

The Syrians' mailed troops were called "Askaris." They were paid regular mounted archers who wore mail coats and helmets, and carried lances, small round shields, broadswords and/or maces for close combat. (Author's note: the scimitar was not introduced until the 14th century) Shirkuh's army, therefore, is divided into the following contingents:

The Horns Contingent: As feudal Amir of Horns, Shirkuh commanded a standing army of approximately 1,000 Askaris. Except in cases of severe danger of invasion of the homeland, only 1/2 of an Amir's retinue usually accompaned him to battle. Shirkuh's personal force in this expedition probably numbered 500, of which 250 could be classified as elite mamluks.

The Kurdish Light Horse Archers: The Syrian Army's left flank was composed of a Kurdish contingent (TB) who were probably the light horse archers referred to by William of Tyre. Given William's proportions, this force consisted of 500 light cavalry armed with bow, lance, sword and/or mace.

The Syrians of Nur ad-Din: The remaining 1,000 Syrians were from the Askar of Nur ad-Din. Part of this force included his personal bodyguard of Mamluk's; their presence would insure the loyalty of Skikuh. The Nuriyya Amirs included the young Saladin, Skirkuh's nephew, who was at this time the Shinar (Police Commandant) of Damascus. There were about 100 elite mamluks and 100 Askari's under Saladin's command in this group.

The Bedouins: According to William of Tyre, Shirkuh recruited Beclouin cavalry from the Taihi and Qarshi clans near Alexandria (MQ). Alternative sources that describe a slightly earlier period ascribe about 400 Taihi Bedouins available for service under the Fatimids. The Qarshi was a minor clan and could probably field 150-200 men. Thus, an average estimate here would be 350 Taihi and 150 Qarshi light cavalry, armed with lance and shield.

The Franks: Christian forces present in this engagement were entirely mounted. William of Tyre cited 374 Knights in the Christian force, accompanied by an unspecified number of Turcopoles. As a rule, Turcopoles usually equalled the number of Knights in most engagements. Thus, there should be 350-400 each of these two types, arnred with lance and shield. lbn Tashribardi's reference to lbn Nizan, a Christian, as commander of the Franco-Egyptian right flank would indicate that he commanded Turcopoles. (Author's note: Small contends that the Turcopoles may have included some horse archers)

The Fatimids: There are almost no sources that describe the composition of the Fatimid force at A]-Babayn. Piecing together several sources (abu Shama, Bar Hebraeus, lbn Tashribardi) an estimate may be made that there were 3,600 cavalry available for the battle. The Fatimid Army had been subject to widespread purging of the officer corps just prior to this campaign and a large proportion of these units would be C, D, and E in morale grades.

THE BATTLE

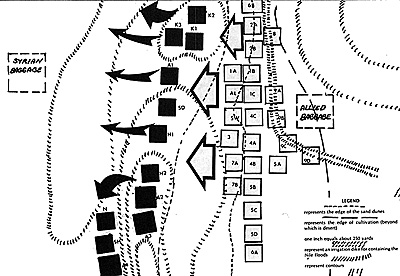

The battle of Al-Babayn may be reenacted as a wargame especially noteworthy for its mobility as a cavalry battle. Special attention should be paid to its terrain. The area marked "sand dunes" slows movement and should eliminate charge bonuses for cavalry attacking uphill. Hills should be placed to hide Shirkuh's division from view from both the Franco-Egyptian and Syrian camps. Hills should be arranged to create a series of depressions that are not visible to each other. Therefore, additions and deductions for morale reaction tests should be limited strictly to anything a unit can sight from its specific vantage point.

Although it is difficult to recreate the effects of Shirkuh's plan in its entirety, a conditional move to force the Fraco- Egyptians to launch the initial charge should add authenticity to this scenario. Furthermore, it would be useful to designate three commanders: one Syrian, one Frankish and one Egyptian. This systems will lead to only one victorious commander; even if the Franco-Egyptian army defeats the Syrian army, only the Franks or the Egyptians may be declared to be the victor. This victory condition may be judged on the basis of possession of the field, casualties inflicted, and/or booty captured.

Initial Skirmishing

Shirkuh dispatched his Bedouins at dawn to harass and delay the Franco-Egyptian army. After some minor skirmishing between both sides' Bedouins, Shirkuh's troops retired drawing Shawar's Bedouins after them all the way to Alexandria (MQ). There is no further mention of either sides' Bedouins during this action. By noon, both armies finally faced each other.

Shirkuh chose his position well. He deployed his army on the edge of a cultivated valley and on a series of hills, whose eastern slopes were covered with sand dunes. His troops held the higher ground, and this disposition channeled the enemy to charge through those dunes uphill (WT).Joseph's River protected both flanks. Saladin commanded the center with about 500 of the least experienced askaris 0A) as well as all of the pack animals from the baggage train, to make his force appear larger than it actually was. 500 Kurdish light horse archers were stationed on the left flank, and 500 more Askaris on the hidden western side of the hill.

The Franco-Egyptians concentrated their initial charge against Saladin's force, believing that he commanded the best troops there. Saladin staged a tactical feint, drawing on the attackers with archery in good order. Meanwhile, the heaviest Allied cavalry pursued Saladin and Shirkuh charged the remaining Syrian troops scattering them.

Shirkuh's Charge

The Knights and Fatimids that pursued Saladin believed that they had gained a victory and stopped to pillage the Syrian camp. Meanwhile, the actual climax of the battle took place when the Allies' reserve force charged the Syrian right flank. They assumed incorrectly that it was under Saladin's command and consisted of inferior troops. As they approached the hill, Shirkuh charged in perfect timing with his right flank force.

The Allies panicked and fled in dissorder; Shirkuh then turned and crushed the Fatimid infantry that was guarding the Allied baggage train. When the Allied force that plundered the Syrian camp returned to the battlefield, they were confronted front and rear by the combined assault of Skirkuh and Saladin (B & BH). This combination proved to be more than they could stand and they routed off the field.

Order of Battle

Franco-Egyptian Forces

Christians: Each knight unit = 100 men (3-5 figures); each Turcopier unit = 180 men (6-9 figures).

1a = Templars EHC (res A) Ian/swd

AL = Knights EHC (irg B) Ian/swd

1b = Knights EHC (irg Q Ian/swd

1c = Knights HC (irg Q Ian/swd

2a = Turcop MC (irg D) Ian/swd

2b = Turcop MC (irg D) comp. bow/mace

Fatamid each unit 240 men or 8-12 figures

Cavalry

SW = Bodyguard HC (reg B) Ian/swd

3 Hv. cav. HC (reg Q Ian/swd

4a Md. cav. MC (reg D) Ian/swd

4b = Md. cav. MC (reg D) Ian/swd

5a = Lt. cav. LC (reg D) Ian/swd

5b = Lt. cav. LC (reg D) Ian/swd

5c = Lt. cav. LC (reg D) Ian/swd

6a = Hr. arc. LC (irr D) comp. bow/mace

6b = Hr. arc. LC (irr D) comp. bow/mace

7a = H r. arc. HC (irr D) comp. bow/lan/swd

7b = Hr. arc. HC (irr D) comp. bow/lan/swd

8 = Bedouins LC (irr D) Ian/swd

Infantry 9a, c, d = Infan 1/2 LI (irr D) sp/shd/swd

1/2 LI (irr D) bow

9b = Infan 1/2 MI (irr D) sp/shd/swd

1/2 LI (irr D) bow

Syrian forces Each unit = 180 men (6-9 figures)

NOTE: ask = Askari, armed with comp. bow, lance, small shield, swd. or mace.

SH = Horns ask. HC (reg B)

SD = Salad. ask. HC (reg C)

H1 = Horns ask. HC (reg C)

H2 = Horns ask. HC (reg C)

N Nur. ask. HC (reg B)

Al Syr. ask. HC (reg C)

A2 Syr. ask. HC (reg C)

A3 Syr. ask. HC (reg C)

A3 Syr. ask. HC (reg C)

K1 Kurd hr. ar. MC (irr D) comp. bow/mace

K2 Kurd hr. ar. LC (irr D) bow/mace

K3 Kurd hr. ar. LC (irr D) bow/mace

SOURCES

Modern accounts of the battle

Deipech, H. La Tactique au XIIIeme siecle (Paris 1886) vol. II pp 209-13

Grousset, R. Histoire Des Croisades et du Royaume, Franc de Jerusalem (Paris 1934-6) pp. 489-93

Heath, Ian Armies and Enemies of the Crusades: 1096-1291 (London, 1978) pp. 52-3

Rohricht, R. Geschichte des Konisreichs Jerusalem (Innsbruck 1898) pp. 326-7

Runciman, S. A History of the Crusades (Cambridge, 1952) vol. II p. 374

Schlumberger, G. Campagnes du Roi Amaury 1er de Jerusalem in Egypte (Paris 1906) pp 136-46

Smail, R.C. Crusading Warfare (Cambridge 1956) pp 131-2, 183-185

There is also usually a brief account of the battle in every biography of Saladin, or history of the Crusades. On Saladin's military forces see:

Gibb, H.A.R. "The Armies of Saladin" in R. Rolk editor, Studies on the Civilization of Islam (Boston 1962) pp 74-90. (it is a reprint of a 1951 article)

Medieval Sources

(AS) Abu Shama The History of the Zangid and Ayyubid Dynasties (Selections of the arabic text with a translation to French in Recueil des Historiens des Croisades (=RHC), Hist. or vol IV (pp131-2): he basically paraphrases Ibn ak Athir's account.

(BH) Bar Hebraeus Chronography (Oxford 1932) Translated from

Syriac by E.A.W. Budge; vol I pp 290-1: He

was a Jewish Physician who wrote a history of

the world in Syriac, containing detailed ac-

counts of the period of the Crusades. For the

battle of Babayn he basically seems to rely on

Ibn al-Athir, however, he does add some addi-

tional interesting facts.

(IA) Ibn al-Athir The Universal History (al-Kamil fi al-Tarikh):

(Selecctions of the arabic text with a french

translation in RHC Hist or vol 1, pp 547-9) He

is one of the most important arabic sources

for this time. He was a courtier for the Zengid

princes, and gives the account from the Syrian

point of view.

(TB) Ibn Tashribardi The Kings of Egypt and Cairo (Al-Najum al-

zahirs fi muluk Misr wa al-Qahira) un-

translated. Cairo edition, 1935, vol 5 pp 348-9.

Although writing in the 15th century, Ibn

Tashribardi collected materials from many

sources, some of which now are lost, for a

history of the Islamic Kings of Egypt. He and

Maqrizi both reflect a Fatimid postion, and in-

clude many details of Fatimid activities which

don't occur in other sources. Apparently they

had access to now lost Fatimid records of the

period.

(MQ) Maqrizi History of the Fatimid Caliphs (Itti'az ai-

hunafa bi akhbar al-A'ima al-Fatimiggin al-

Khulafa) untranslated. Cairo edition, 1973, vol

3 pp 383-4. Maqrizi was one of the greatest

historians of the middle ages of any nation

(who also claimed descent from the Fatimid

Caliphs). He wrote a number of invaluable

works, of which only a small portion have been

translated. This work, seemingly based in par on

now lost Fatimid records, contains much crucial

information on Fatimid Egypt.

(WT) William of Tyre A History of Deeds done beyond the Sea (Rerurn

in Partibus Transmarinsi Cestarum) translated by

E.W. Babcock, (Columbia 1943) English version vol

2 pp 331-4 Latin in RHC Hist occ. vol I pp 925-7

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. IV #1

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1982 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com