ED NOTE: This article was edited from a series on Napoleonic tactics by G. Jeffrey. The series will be published in one volume by THE COURIER PUBLISHING CO. as a preamble and adjunct to Jeffrey's VLB rules.

This brief look at tactics and battle-handling is meant to give a general knowledge of the differences between the two major tactical systems employed during the period.

Many people speak of tactics when, in fact, they are referring to the battle-handling of troops in the field. Tactics are the methods by which units and formations are brought from one form of deployment to another, and are, consequently, about formation changes during the Napoleonic period, whether by individual units (elementary tactics), or by higher formations (grand tactics). On the other hand, battle-handling is a term refering to the manner in which a commander uses his forces to achieve his objective. The formations he causes his units to adopt have a bearing on the outcome of his engagements, but will not of necessity determine the outcome of his operations. Battle-handling is about the use of formations and deployments, while tactics is about getting from one formation to another.

THE TWO SYSTEMS

There were two systems of tactics practiced during the period, which may be classified as the PRUSSIAN and the FRENCH systems. The French system was not a completely new one, or wholly different from the other, consisting of the Prussian system 'with embellishments', these being the product of new concepts in tactical thinking engendered by the works of the Conte de Guibert. However, since the products of Guibert's thinking became so widely-used as to almost eliminate the use of the other system entirely, it is fair to regard the two systems as separate.

The Prussian system was based on the linear formation, both for movements in full line by units and for movements in column. In the latter case the movements were effected by sub-units, each of which marched and wheeled in an individual line. The practice was for subunits to be moved and wheeled around in line until they reached their desired positions in the new formation.

This meant that intervals had to be maintained in column formations between sub-units equal to their own length so that they could wheel out of the column when required - forming what were called Open Columns. The French system introduced the alternative of the march by files - in which the sub-unit is turned to left or right and then marches 'in threes'. This allowed the subunits to be closed up when in column formations, known as closed columns, with their intervals reduced to 3 yards. This greatly reduced the amount of ground that they had to cover when they were required to deploy, thus speeding up the rate at which changes of formation could be effected. The French marched at the same rate but employed a shorter pace (thus covering less ground per minute) than their opponents, but since they 'did not have so far to go' when deploying they appeared to move faster.

Both systems were based on maintaining proper numerical order from right to left when in line, and the Prussian system also insisted on sub-units being in proper numerical order from front to rear when in columns. The French system introduced 'inversion', or the deployment of subunits in reverse numerical order when in column, which for some reason did not extend to their placement in line, where proper order from the right remained the order of the day. When columns were marching in inverted order they were returned to line by reversing the methods for deploying to right and left.

The two systems also differed in their attitude to grand movements. The Prussian system required that units maintain their alignment on one another at all times during marches in line (or in a line of columns). The French system advocated that this was not necessary provided a halt was made and units returned to their correct alignment with one another prior to any engagement.

Another vital difference was the use by the French of the wheel on a moving pivot. The Prussian system employed a wheel on a fixed pivot. Here the 'inside man' remains on the wheeling point, marking time, while the remainder of the sub-unit come round in line with one another using him as a pivot. The French pivot man took very short steps in order to clear the pivot point for the following sub-unit.

The importance of this might not be obvious, however it cannot be over-stated. Since the sub-units were deployed at intervals equal to their own length from one another under the Prussian system, one sub-unit was still 'on' the pivot point when that following arrived, so that a 'queue' formed. Once the first sub-unit had completed its wheel and the next in the column started to wheel in its turn, the interval between the two had, increased to 11/2 times the length of the first sub-unit. This occurred with every sub-unit in succession so that the unit as a whole ended up occupying a 50% greater length and had to halt and rectify this, all of which added to the time taken to deploy units in the field.

With the French system, since the pivot point was vacated almost immediately by the inside man of each sub-unit as it arrived at the wheeling point, following sub-units were able to commence wheeling immediately they arrived there, with the result that no distance was lost between the sub-units in column and no 'queuing' was necessary at the pivot point. The same situation existed under the Prussian system so long as wheels were of less than 60 degrees.

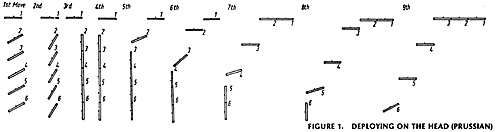

The function of tactics it to permit bodies of troops to be bought from one formation to another in the minimum of time consistent with their good order and safety. The classic examples of the great differences between the two systems of tactics practiced during the period - and of the great superiority of the French over the Prussian system are the deployments from column into line facing in the direction that the column had been moving and to the right of the column. In the former, which had to be effected from an open column under the Prussian system, the leading sub-unit (on which the line was formed), stood still, while the remainder formed line on its left by first wheeling backwards into line at right angles to the leading sub-unit.

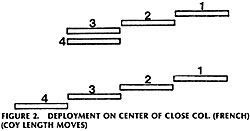

Then they marched directly forward, wheeling to the right and coming up into line with the leading sub-unit as they reached the right flank of their own positions in the line as shown in Figure 1. Under the French system, where the use of the march by files permitted the unit to be in close column in the first place, the leading sub-unit stood fast while the remainder turned to the left, marched clear of one another, then faced their front again and marched the few yards up into line as shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2. DEPLOYMENT ON CENTER OF CLOSE COL. (FRENCH) (COY LENGTH MOVES)

FIGURE 2. DEPLOYMENT ON CENTER OF CLOSE COL. (FRENCH) (COY LENGTH MOVES)

Units using the Prussian tactical system took four times the time taken by units using the French system to effect the deployment. This was further aggravated since in the French system, it was possible to deploy on any of the subunits. Thus, if it took 5 minutes to deploy using the French system, it could take anywhere from 20 - 30 minutes to effect the same movement using the Prussian system.

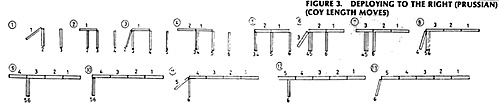

The deployment of a unit to the right under the Prussian system was slowed down' by the use of the wheel on a f ixed pivot (figure 3).

The first sub-unit wheeled to its right, and the

remainder marched along behind it, wheeling right in

succession and coming into line with the right-hand subunit.

A 'queue' of sub-units built up behind the forming line. The

time difference ratio could range from 5:4 to 6:1 depending on

whether or not the commander using the French system had

had the foresight to invert the order of his column beforehand.

The first sub-unit wheeled to its right, and the

remainder marched along behind it, wheeling right in

succession and coming into line with the right-hand subunit.

A 'queue' of sub-units built up behind the forming line. The

time difference ratio could range from 5:4 to 6:1 depending on

whether or not the commander using the French system had

had the foresight to invert the order of his column beforehand.

The general inefficiency of their troops' weapons meant that commanders were compelled to employ them in very large numbers in order to achieve definite results. It also meant that engagements between hostile formations were generally very localised affairs, even when one side was in the main line of battle, since about all the help that could be expected from formations on either side - unless they were prepared to quit the line of battle and permit the enemy to exploit the gaps thus created - was from their batteries.

For this reason, defence in depth was necessary - so that formations were deployed one behind the other in order that, should the first break, there was one to hand to take over from it. The basic line of battle consisted, consequently, of two lines of troops, with brigades being deployed one behind the other in a division, and divisions being deployed one behind the other in a corps. The lines thus formed were posted some 100-200 yards behind one another in order that, should one be beaten, it would not disrupt the one behind.

MARCHES

There are two factors to be considered when marching towards the enemy. The first is that the more rapidly one can approach the enemy the less time one gives him to take counter measures against one's advance. The second is that one should have one's troops deployed so as to be able to counter any action taken by the enemy. As a general rule , the further that one is from the enemy the less one has to give priority to safety, and the more one can concentrate on speed of advance, while, the closer one comes to hostile forces, the more one must consider security and the less vital becomes the rate of one's advance.

The rate at which one can move a body of troops across any piece of terrain is affected by the width of the formation in which they are deployed (this applies equally to a single unit as it does to a group of units in line with one another) with the rate being reduced by every increase in the formation's width. Thus, if a brigade of four units is placed in a brigade column, with each unit being deployed in line one behind the other, the rate of movement that it may achieve will be the same as could be achieved by a single unit in line, while, if the brigade is placed in a line of four units, the rate of advance would necessarily be slower owing to the far greater difficulty of maintaining their alignment.

Owing to the difficulty of deploying into line experienced by commanders using the Prussian tactical system, and to the time-consuming procedures that were employed, it was not wise to make approach marches to points close to the enemy. The most common situation was to deploy in line of battle at a considerable distance from the enemy, march towards him in line of battle, and then, if one was attacking, simply launch one's attacks in that formation. Under the French system, where a far greater degree of flexibility existed, approach marches could be made to points much nearer the enemy's positions - say to within a few hundred yards, which greatly reduced the time available to opposing commanders to make counter movements - these being followed by rapid deployments based on the march by files, followed by equally rapid attacks against the enemy's positions.

APPROACH MARCHES

Approach marches, that is a march to the point at which the troops were to deploy into line of battle (whether of line or of columns) were made in grand columns. The deployments

into line of battle that were effected from them were based on the same general principles as were those made by individual units - in this case with units replacing sub-units as the basic element of maneouvre. There were several methods of forming line of battle from a marching column, which were all designed to produce the same end result, namely the formation in a line of units of the force in the correct numerical order of units from the right.

Approach marches, that is a march to the point at which the troops were to deploy into line of battle (whether of line or of columns) were made in grand columns. The deployments

into line of battle that were effected from them were based on the same general principles as were those made by individual units - in this case with units replacing sub-units as the basic element of maneouvre. There were several methods of forming line of battle from a marching column, which were all designed to produce the same end result, namely the formation in a line of units of the force in the correct numerical order of units from the right.

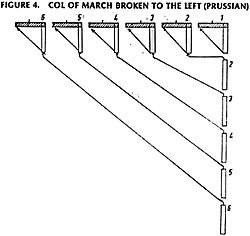

Under the Prussian system the most straightforward deployment of a grand column was that effected to the left of the leading unit (Figure 4). All of the following units broke from the column once the leading one had arrived at its deploying ground and then marched to their own positions where if required, they then formed into line.

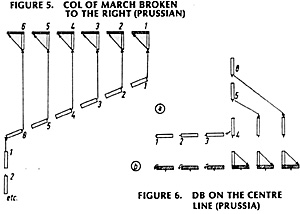

If the line was to be formed on the right of the route taken by the column, the whole force had to wheel to the right. The angle of the wheel depended on the distance between the point at which they wheeled and the point on which they were to deploy. The column was marched obliquely to its intended line, at which point (figure 5) the units wheeled left and came up to the deploying line on their own positions, where they could then deploy if required.

If the line was to be formed on the right of the route taken by the column, the whole force had to wheel to the right. The angle of the wheel depended on the distance between the point at which they wheeled and the point on which they were to deploy. The column was marched obliquely to its intended line, at which point (figure 5) the units wheeled left and came up to the deploying line on their own positions, where they could then deploy if required.

Where the line of battle was required to be formed on a unit other than that leading the column, and the force was at or slightly behind the deploying point, a combination of the previous two methods of deploying was employed as shown in Figure 6.

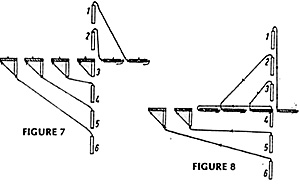

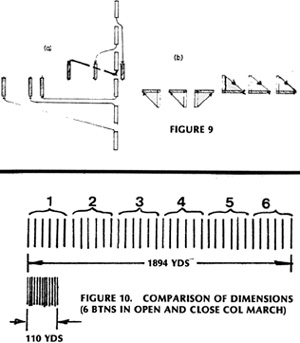

Where part of the force had already passed the line to be formed on, those units beyond it had to wheel through 180 degrees and return to their positions (Figure 7) while the others made a normal deployment. Under the French system of tactics, where the introduction of the countermarch had permitted units to deploy into line facing to the rear of the direction they faced in column, the methods of deployment shown at Figures 8 and 9 were used, much speeding up the methods employed under the Prussian system.

Where part of the force had already passed the line to be formed on, those units beyond it had to wheel through 180 degrees and return to their positions (Figure 7) while the others made a normal deployment. Under the French system of tactics, where the introduction of the countermarch had permitted units to deploy into line facing to the rear of the direction they faced in column, the methods of deployment shown at Figures 8 and 9 were used, much speeding up the methods employed under the Prussian system.

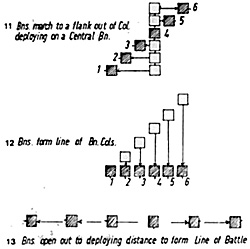

The major difference between the Prussian and French systems of deploying into line of battle from grand columns was brought about by the use by the latter of the march by files and close columns. Figure 10 shows the different depths of a force of 6 battalions when in open

column, as required for Prussian tactical deployments, and in close column, as permitted by the French tactical system. Under the French system, the basic maneuver, after the relevant unit had been nominated as that on which the deployment was to be affected, was for all other units to face right, if ahead of the unit of manuever, or left, if behind it, and then march in file out

of the column until they had cleared the units to their flanks, as shown in Figure 11.

The major difference between the Prussian and French systems of deploying into line of battle from grand columns was brought about by the use by the latter of the march by files and close columns. Figure 10 shows the different depths of a force of 6 battalions when in open

column, as required for Prussian tactical deployments, and in close column, as permitted by the French tactical system. Under the French system, the basic maneuver, after the relevant unit had been nominated as that on which the deployment was to be affected, was for all other units to face right, if ahead of the unit of manuever, or left, if behind it, and then march in file out

of the column until they had cleared the units to their flanks, as shown in Figure 11.

Having arrived at that point, the units then faced to the front, marched into line with one another, and then 'opened out' by marches by files to the correct deploying distance. They then deployed, if required, as shown in Figures 12 and 13. This method of deploying, like that of deploying a single unit from close column, could be effected on any of the units of the grand column.

DEPLOYED MARCHES

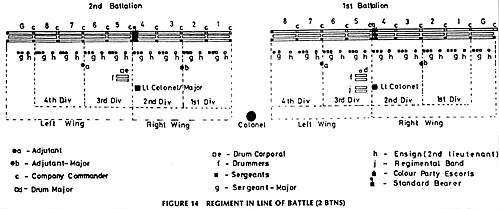

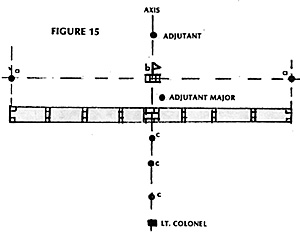

The most difficult maneuver of all was the march in deployed order - whether in line of columns or line of lines. I have shown the basic infantry regiment in line of battle in Figure 14, showing the different internal groupings by which the sub-units were known and the placement of the commanders. It will be seen that all of the command structure of the battalion and regiment was behind the unit, making it difficult to amend its movements easily (eg. no 'Right boys, follow me' stuff!). Figure 15 shows the position of the important officers

and NCO's when a battalion was ordered to advance, including the placement of the directing sergeants on the flanks, (a), and the colours and adjutants as forward guides, with the battalion commander behind the centre keeping the axis in the right direction by aligning it on three other Sgts, (c). It was not an easy task to march a battalion or cavalry regiment forward in line on a given axis.

The most difficult maneuver of all was the march in deployed order - whether in line of columns or line of lines. I have shown the basic infantry regiment in line of battle in Figure 14, showing the different internal groupings by which the sub-units were known and the placement of the commanders. It will be seen that all of the command structure of the battalion and regiment was behind the unit, making it difficult to amend its movements easily (eg. no 'Right boys, follow me' stuff!). Figure 15 shows the position of the important officers

and NCO's when a battalion was ordered to advance, including the placement of the directing sergeants on the flanks, (a), and the colours and adjutants as forward guides, with the battalion commander behind the centre keeping the axis in the right direction by aligning it on three other Sgts, (c). It was not an easy task to march a battalion or cavalry regiment forward in line on a given axis.

Where several units were required to march in line with one another one was selected as the 'directing unit', and guides were posted on the line of its axis. The other units maintained their alignment on the directing unit by posting the flank sergeants ahead of their flanks and the colours ahead of their centres when they were in line. These directors maintained their alignment with one another, and the units maintained their own alignment on their own directors (Figure 16). Where a march in echelon was made, the directing unit was always the flank unit of the leading element (the right-hand unit whenever possible). The same principles applied when

marching in lines of columns, except that the colours were posted in the centre of the unit mass.

Where several units were required to march in line with one another one was selected as the 'directing unit', and guides were posted on the line of its axis. The other units maintained their alignment on the directing unit by posting the flank sergeants ahead of their flanks and the colours ahead of their centres when they were in line. These directors maintained their alignment with one another, and the units maintained their own alignment on their own directors (Figure 16). Where a march in echelon was made, the directing unit was always the flank unit of the leading element (the right-hand unit whenever possible). The same principles applied when

marching in lines of columns, except that the colours were posted in the centre of the unit mass.

Wheels in line were not made by forces of larger than a single unit as an entity, but were made individually by units within the over-all context of the major curve as shown in Figure 17. The new line was 'marked' by the posting of guides on the flank positions of the units. The whole force moved forward until it reached the pivot point of the inside unit, at which point the force commander gave the order to wheel, this then being repeated by unit commanders in succession. The inside unit wheeled fully into its new position, the others doing so gradually as they continued to advance so as to bring themselves into their new positions. The British infantry, alone of all the period's infantries, employed a backwheel on their outer flanks rather than a normal wheel on the inside flank.

Wheels in line were not made by forces of larger than a single unit as an entity, but were made individually by units within the over-all context of the major curve as shown in Figure 17. The new line was 'marked' by the posting of guides on the flank positions of the units. The whole force moved forward until it reached the pivot point of the inside unit, at which point the force commander gave the order to wheel, this then being repeated by unit commanders in succession. The inside unit wheeled fully into its new position, the others doing so gradually as they continued to advance so as to bring themselves into their new positions. The British infantry, alone of all the period's infantries, employed a backwheel on their outer flanks rather than a normal wheel on the inside flank.

Diagrams 16-24 (Large: 56K)

Diagrams 16-24 (Jumbo: slow: 193K)

PARALLELISM

In order to be able to effect grand maneuvers it was necessary, where more than one line of troops was involved, that the second and subsequent lines be parallel to the first and at least one unit's length (in line), behind one another. If the lines were not parallel they would not be capable of bringing their effect to bear in the same direction. If the intervals between them were of less than the length of a unit, there would be insufficient room for the redeployment of units prior to the execution of maneuvers. The reason for these precautions is that the period's tactics were based on geometry. The pivoting of parallel lines at the same point on their lengths brings them closer together, culminating at 90 degrees, in their occupying the same 'ground' as shown in Figures 18 and 19.

For this reason, in order that the proper interval could be maintained between lines when they were pivoted, each line behind the first had to be pivoted on a point one interval's length further from the pivot flank as shown in Figure 20 (a) and (b). Thus, while the first line pivoted on its first unit, the second pivoted on its second unit and so on. One result of this was that, after pivoting, the lines were 'offset' from one another by the length of the interval.

CHANGES OF FRONT

The concept of parallelism did not end with the interior structure of the line of battle, but extended into its relationship with that of the enemy. The inability of large formations to quickly re-deploy to meet threats that came from their flank made it better if one's line of battle corresponded to that of the enemy. Moving a body of troops and a number of units from one deployment facing in a given direction to another facing in a different direction was not simply a case of telling the unit commanders to 'get on with it.'

Such a situation, with units moving independently of one another would inevitably lead to confusion as units tried to 'cross one another's paths' and to excessive re-alignment once the movement had been completed. To avoid these dangers precise procedures were laid down for the execution of changes of front, which were controlled by the officer commanding the force.

Figure 21 shows a change of front on a fIank - the full 90 degree pivot being shown. Pivoting both lines on their inside units would have brought them onto the same line. The second was, consequently, pivoted on its second unit, the first of that line failing back into place on the right of the line. The maneuver was effected by forming column facing in the direction in which they would be required to move, the first of the second line doing so in the opposite direction. The columns than marched onto their new ground (marked by the positioning of sergeants) and re-deploy into line. Sometimes a change of front was required to be effected by a backwards pivot of the line of battle (Figure 22). Under the Prussian system the subsequent deployment into line was effected by forming line to the left of the column, these having performed a 90 degree wheel from the positions shown in the Figure.

Changes of front through less than 90 degrees were effected as shown in Figure 23 where the flank was the pivot point. They were then re-aligned by 'dressing back' the second and subsequent lines to the proper interval, which had to be done before effecting any other change of front or deployment into column. Where the centre of the line was taken as the pivot (Fig. 24) the central units wheeled in line, those adjacent to them marching and wheeling in line and the remainder forming columns as normal for their matches. Changes of front were effected on the same numbered unit in each line where they were of less than 90 degrees, and required a subsequent realignment of the following lines.

Changes of front through 90 degrees did not require further re-alignment of the following lines. Where changes of front through greater than 90 degrees were required they were effected by fronting to the rear, by which, after forming columns, the units marched to their rear into the new positions.

GRAND COLUMNS

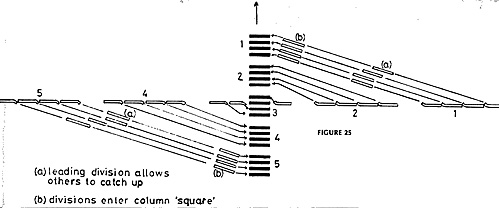

Marches in line of a number of units were difficult to execute, and were also slow of execution owing to the difficulty of maintaining alignment and the need to halt frequently to redress the line. To meet the main requirement of approach marches they were made in grand columns, each unit of the force being deployed, either in line or column, one behind the other. Forming a grand column under the Prussian system was done by having all of the units form column to the right then marching off behind the righthand unit, which wheeled as it stepped off to bring it into the required direction. In the French system this maneuver could also be employed. It could also be effected by inversion, in which case the column was formed to the left, placing the units and subunits in

reverse numerical order. The more ususal method of forming grand column practiced under the French system, was the formation of close grand column as shown in Figure 25.

In the French system this maneuver could also be employed. It could also be effected by inversion, in which case the column was formed to the left, placing the units and subunits in

reverse numerical order. The more ususal method of forming grand column practiced under the French system, was the formation of close grand column as shown in Figure 25.

CONCLUSION

Reading this brief will it is hoped, illustrate the great difficuly that attended maneuvers during the Napoleonic period. The best way of learning what the problems are, and the time factors involved in grand maneouvres is to; set the troops out and go through the movements that were prescribed (and those that weren't) to see why they had to be done as they were.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. III #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1982 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com