This article is a potpourri of ideas on the general

theme of providing more interesting and challenging naval

games. The various concepts are not necessarily closely

nor directly interrelated. The specific examples which I will

discuss are for 20th century naval situations; however,

most of the ideas have equivalent or analog counterparts in

many historical periods.

This article is a potpourri of ideas on the general

theme of providing more interesting and challenging naval

games. The various concepts are not necessarily closely

nor directly interrelated. The specific examples which I will

discuss are for 20th century naval situations; however,

most of the ideas have equivalent or analog counterparts in

many historical periods.

"He who fights and runs away . . . "

Every reader can complete the above quotation, although he may not recall that the phrase is attributed to Demosthenes (338 B.C.), with many variations having been recited by various military leaders over the years. In any event, the thought behind the quotation provides the rationale for wargaming a campaign, rather than a one time battle or engagement. If there is no reason to husband resources for some future encounter, there may be considerable incentive to attempt to win a battle with meaningless kamikaze tactics.

The suicide incentive is especially strong when the only victory conditions are to sink the most enemy ships. This is not to say that situations might not arise in which fighting to the last man is important; I simply make the point that, in most cases, there are strategic as well as tactical objectives which govern the actions of a military commander.

Land or naval campaigns generally involve the use of a strategic map of some region where the forces move and maneuver until they make contact. The forces which come into contact either attempt to defeat the enemy or withdraw, depending on the circumstances. Avalon Hill boardgame JUTLAND provides the setting for the engagements between British and German naval forces in the North Sea during World War I.

The out-of-print Simulations Publications, Inc. game, FLIGHT OF THE GOEBEN simulates the strategic situation in the Mediterranean Sea at the outbreak of the first World War. The boardgames BISMARK (Avalon Hill) and NORTH CAPE (C-in-C) provide strategic maps and order of battle data for the North Atlantic convoy routes during World War II. The maps and counters for the games mentioned (and others) can be used to generate the strategic events which trigger the tactical encounters. The two-volume set, Chronology of the War at Sea 1939- 1945 by J. Rohwer and G. Hummelchem (published by Arco, 1974) is a goldmine of information from which scenarios for any theater of war could be constructed. In addition, the gamer can invoke historical "what if s" or his imagination (as will be described later) to invent campaigns and scenarios.

When a map campaign is used to provide the basis for tactical encounters, some type of hidden movement is often used. The services of a gamemaster or referee may be used to monitor the locations of the forces and to inform the players when contact has been made. If a third person is not used, then some form of "hex-calling" or coordinate-calling may be used to determine when two forces come into the same area.

The disadvantage of the "calling-search" is that it gives clues to both sides about the location of opposing forces which they would not generally have. The "matchbox system" described by Featherstone is an excellent (all-be- it cumbersome and expensive) way to provide for hidden movement and search without the two sides gaining intelligence from the searching procedure.

I have devised an equivalent procedure which can be used for strategic or tactical searches provided there is only a small number of units (or groups of units) on either side . . . say 4-6. The search method is suitable for situations in which contact is made in the same or adjacent hex or square. The method is not very suitable when the units which are searching have a long search range and can look into a large number of hexes or squares.

Matchbox Method

Perhaps the best way to understand my proposed method is to describe the "matchbox system" discussed by Featherstone in his book Naval War Games. A matrix of penny matchboxes is constructed, such that each drawer in the matrix represents a coordinate location (grid square or hex) on the campaign map.

The friendly player places a marker in each drawer which represents a location in which he has units. The enemy player may examine the contents of drawers representing locations which he is eligible to search by virtue of ships, aircraft or submarines located on his campaign map. If the enemy player discovers a drawer containing a friendly unit marker, he has made contact with that unit.

The process would be repeated reversing the roles of the friendly and enemy players (or use two separate matrices, one for each side). The basic concept is sound; however, the physical bulk of the set of matchboxes and the time required to construct the matrix (or two matrices) tends to discourage implementation of the method. For example, a standard map of 30x60 = 1800 hexes or coordinate squares would require a matrix of boxes having dimensions of about 30"x15"x1 1/2".

My proposed system consists of two special sets of

card files, one set for each player . . . analogous to a

matchbox matrix for each player. a direct analog of the

original matchbox scheme would require two decks of

cards, each several inches thick. For example, the 1800

hexes (or squares) would require 1800 cards which would

approximate the thickness of an unabridged dictionary.

The special nature of my proposal is that each player's

deck consists of two parts and, as a result, the system is

more compact than one might expect.

My proposed system consists of two special sets of

card files, one set for each player . . . analogous to a

matchbox matrix for each player. a direct analog of the

original matchbox scheme would require two decks of

cards, each several inches thick. For example, the 1800

hexes (or squares) would require 1800 cards which would

approximate the thickness of an unabridged dictionary.

The special nature of my proposal is that each player's

deck consists of two parts and, as a result, the system is

more compact than one might expect.

Part A of each player's set contains one card for each value of the more numerous grid coordinate (e.g., cards numbered 1-60 in our example). Part B of each deck contains N sets of cards, each set containing a card for every value of the least numerous grid coordinate (e.g., N sets of cards numbered 1-30 in our sample). The number N is the number of independent units or groups of units which can be searched for. Obviously coordinate systems which use combinations of letters and numbers (such as the Avalon Hill boardgames) can also be handled by my technique.

Suppose that the friendly player (designated by F) has four independent units which the enemy player can look for. Suppose that the enemy player (designated E) has five independent units which the friendly player can search for. The file card decks would be make up as follows:

-

Friendly Player -- Part A-60 cards;

Part B-4 sets of 30 cards

Enemy Player -- Part A-60 cards;

Part B-5 sets of 30 cards

Note that we have replaced 1800 cards for each player (or 3600 total) with 390 (60 + 4x30 plus 60 + 5x30). Each set in Part B is given a designation such as F1, F2, F3 and F4 for the friendly player and E1-E5 for the enemy player.

Each independent unit for each player is represented by two chits bearing the code for a unit such as F1, F2, E1, E2, etc. One chit is placed in the A file at the appropriate value of the more numerous grid coordinate. The second chit is placed in the B file at the value of the second grid coordinate. The unit is placed in the B file which matches its name.

After each player has placed his pairs of chits in the proper file locations, the players exchange files to conduct their searches. Each player looks into the A file at the appropriate grid coordinates which he is eligible to search. If he finds nothing, he is through. If he finds a chit bearing a Part B file designation (such as F2), he can look at that set (F2), and ONLY that set, in part B (F2) at the second grid coordinate corresponding to his search location which was successful in Part A.

The following example illustrates the procedure. Note that my example is also chosen to illustrate the fact that the A file is made to represent the more numerous grid coordinate regardless of whether it happens to be the first part of the coordinate location or not. Also, as noted, either of the parts of the file could use alphabetical grid coordinates in place of the numbers used in the example.

EXAMPLE: coordinate system numbers are XXYY; where XX = 1-30, YY = 1-60

| friendly units | enemy units |

|---|---|

| F1 in 1033 | E1 in 0633 |

| F2 in 1252 | E2 in 1013 |

| F3 in 2015 | E3 in 1030 |

| F4 in 3010 | - |

Assume that units may only search the hex in which they are located in order to establish contact.

| Enemy File | |

|---|---|

| Part A (YY) | Part B (XX) |

| E1 at 33 | E1 at 06 in set E1 |

| E2 at 13 | E2 at 10 in set E2 |

| E3 at 30 | E3 at 10 in set E3 |

The friendly player is eligible to look in the enemy A file at 33, 52,15 and 10. He will find only the E1 at 33; but when he looks in the E1 file at location 10 he will not find the second chit. Note that he is NOT eligible to look into the E2 and E3 files to discover the 10s there since he did not find the E2 or E3 markers in the A file. Also note that unit F4 in 3010 cannot accidentally discover E3 in 1030 because of the way in which the search is conducted.

In the above example no contact is made. The enemy player would conduct his search in a similar manner. Unless the other player had aircraft or submarines which enabled him to search some locations not available to the friendly player, the enemy player would not find any contacts either.

There are several advantages to my method as compared with the traditional "hex-calling". First, the two players are able to search simultaneously, which speeds the search procedures. Second, neither player gains knowledge of where the other player is eligible to search. Finally, the equipment is simple and inexpensive. The files can be made or modified easily for a variety of maps.

One disadvantage is that a player may find out one grid coordinate of an opposing unit during an unseccessful search. However, this is less information than he would obtain from the traditional hex-calling. The twostep procedure is a little cumbersome, but worth the effort.

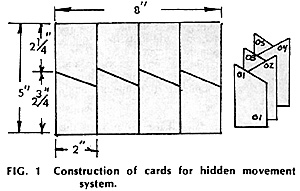

My files were constructed from 5"x8" filing cards by cutting them as illustrated in the diagram. The diagonal cuts are simply an easy way to produce tabs on which the coordinate values can be written. I reverse every other tab (see sketch) so that odd-numbered tabs are left and even- numbered tabs are right. I cut the cards for coordinates 10, 20, 30, etc. from a different color to speed up the searching procedure. I also use different basic colors for each set in Part B to make the sets easy to distinguish from each other.

Cards of the size shown in the sketch can be stored in a crush-proof cigarette box. Thus, we might dub the proposed method the "cigarette pack" search method. (For those who are interested in computers and programming, my method is analogous to the use of "indirect addressing".)

TACTICAL GRID COORDINATES

Although several of the naval miniatures rules systems provide rules for submarines, only SEEKRIEG provides any explanation of how submarine hidden movement might be implemented. All of the other rules leave the implementation of hidden movement (or related procedures to the imagingation of the players and/or referees.

We have found that a pattern cutting board makes an excellent grid coordinate surface to play on. The boards are made of heavy cardboard, 40" x 72", fold to 12" x 40" and are covered with a one-inch grid. They can be purchased for about six dollars in a sewing store or in the sewing department of a department store. Of course you could make one for yourself, but the readymade version is convenient.

If we substitute centimeters for inches as distances in the GENERAL QUARTERS rules, one pattern board is sufficient for a good cruiserdestroyer engagement. Two boards make a surface large enough for use with the normal distance scale. The grid has a great many useful applications for devising scenarios.

The coordinate system can be used for the following purposes: to define the locations of minefields; to implement hidden movement for submarines, torpedoes, limited visibility, etc.; to locate positions and orientations of ships when a game is interrupted and is to be continued in the future; to provide a reference for executing missions (e.g., pick up downed pilot at XXYY); to provide reference locations for islands, shallows, etc. which can be used at different times and easily relocated, or which may locate features known only to one side or the referees. There are many other possible applications.

Another grid scheme was evolved by Bob Henderson at the Potomac Wargamers. Bob created an "ocean" of one-foot square ceiling tiles. The tiles are painted and interlock to form a playing surface. . . or can be picked up and moved, if you move off of one of the sides of the area. Islands, shallows and other features can be painted on some of the tiles. The one square foot area can be subdivided for the purpose of locating a point or an object with greater precision.

We have found that two or three cruisers and four to eight destroyers per side provide enough ships for an interesting evening. We generally provide aircraft for two or three turns of air attacks, but not enough to overwhelm the scenario. The most obvious way to provide balance of forces is to allot each side the same number of the same types of weapons. We try to produce balance in other ways, some of which give the gamers an opportunity to choose some of his forces (or save some forces for a future scenario). We have used a point system which permits a commander to select forces within some overall limit.

A point value method which works well with the GENERAL QUARTERS rules is to use the sum of the primary and secondary attack factors plus one point per torpedo tube mount. This approach works better than to use only the defensive value as the basis for assigning points. Destroyers would range from 4~; heavy and light cruisers from 5-19. A typical scenario might call for 50-55 points per side with a maximum limit of 30 points of ships larger than DDs. For aircraft we use the AA factor as the point value or 1/3 point per unit for planes with zero AA value. 25-30 factors of aircraft will provide one to three turns of air strikes per game, depening on how the sides whish to allot aircraft. More turns of airpower tend to overwhelm the ship-vs-ship flavor of a game.

If more powerful units such as battleships, battle cruisers or aircraft carriers are to be used, it is possible to provide balance various ways. An engagement conducted under conditions of limited visibility may permit all units to get in close before firing can take place. Such a situation tends to offset disparities in gun ranges and penetration or reduces the capabilitiy of the big ships to stand off and demolish the smaller units.

For example, one might set the basic range of visibility at 10 or 12 thousand yards. A die roll could be used each turn to increase or decrease the basic range (e.g., odd, add the die roll in thousands to increase visibility; even, subtract the die roll in thousands from the present visibility range). Ships may move in and out of contact as the "fog" thins or thickens . . . light forces may be able to conduct torpedo attacks which would otherwise be impossible.

One might also compensate a weaker side by giving additional aircraft. Powerful units can be handicapped by using them in a damaged condition where their full armament strength is not available. A scenario might involve the successful escort of a damaged battleship or carrier across the board. The speed capability of the unit might be reduced and, perhaps, a hull box or two might be crossed off to start.

Also, a damaged ship might have to fire in local control (+1 die roll penalty) because of damage to the firecontrol system, or be permitted to fire only every other turn because of loss of power and damage to the handling system. Finally, one way to limit the impact of a powerful ship is to permit the unit on the board for only a limited number of turns. Perhaps a convoy raider learns that a larger force has been called in; perhaps a unit may "hit and run" because air strikes may be called in if it stays too long, etc.

Another way to influence balance is by assigning victory points to the attainment of certain objectives such as picking up a pilot, bombarding a radar station, laying or sweeping mines, moving a unit across the board, landing a UDT unit, etc. Although it is more difficult to assign numerical values to such tasks, the objectives make for interesting games.

If the scenarios are a part of a continuing series, it is always possible to adjust the points in future. scenarios or to compensate by adjusting the replacement points for the next scenario. We use about 15 points of replacement ships for the next scenario. Any damaged ships may be repaired between scenarios according to the schedule given in the GENERAL QUARTERS rules by specifying how much calendar time is presumed to elapse between scenarios. The same number (25-30) of aircraft points are usually alloted to the next scenario plus any aircraft which may have survived.

Thus, by fostering a "fight another day" philosophy, there is much less tendency to "throw-away" damaged units, engage in last minute and pointless ramming etc. A damaged unit might be fully or partially repaired by the time of the next engagement, but an expended unit would have to be replaced from the limited number of replacement points alloted to the next scenario.

We keep records of the results of the various engagements. Even though different players maV participate from time to time, as we review the records, it seems as though some shops wind up sunk or badly damaged each time and one or two ships per side seem to stand out. The vessels began to get "reputations".

After looking at the records for several scenarios, we decided to reward one ship with a -1 (favorable) die roll correction on the gunnery straddle roll. Another vessel seemed to have had very good torpedo fire control and was awarded a favorable column shift in the torpedo hit table. Such modifications for individual ships are analogous to the crew status increments in sailing ship rules or to the award of ace status to elite aircraft units.

INSTANT SCENARIOS

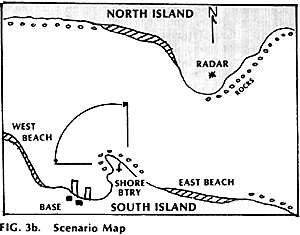

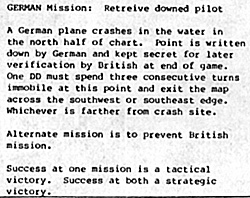

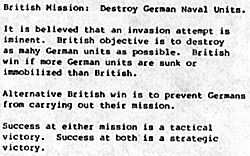

We also used a method for assigning missions and

objectives for scenarios which might be called "instant

scenario". The cards with missions, victory points and

other information are shown in Figure 3. The cards are

tailored to the intelligence summary which was originally

used to provide the rationale for the engagements. Players

simply pulled a card out of a hat to provide the basis for an

evenings gaming.

We also used a method for assigning missions and

objectives for scenarios which might be called "instant

scenario". The cards with missions, victory points and

other information are shown in Figure 3. The cards are

tailored to the intelligence summary which was originally

used to provide the rationale for the engagements. Players

simply pulled a card out of a hat to provide the basis for an

evenings gaming.

Used cards were held out for several games so that the missions and victory conditions would not be repeated too soon. The scenario descriptions which are shown on the sample cards in the figure illustrate a variety of objectives which can be used as the basis for interesting and challenging games.

For those with a flair for the dramatic or historic, the intelligence summary could be typed in an official-looking format. Official stationery for the period is not necessary as many communications were produced on ditto or mimeograph and, hence, were completely typewritten. Typical formats for letters can be found in book illustrations which show historic communications.

For those with a flair for the dramatic or historic, the intelligence summary could be typed in an official-looking format. Official stationery for the period is not necessary as many communications were produced on ditto or mimeograph and, hence, were completely typewritten. Typical formats for letters can be found in book illustrations which show historic communications.

UNREALIZED SCENARIOS

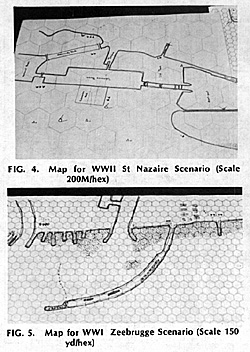

I have not followed Lonnie Gill's advice completely. In the previous sections I have described some ideas for scenarios and games which we have implemented. However, I have two "dream" scenarios which have never been completed: the WWI British raid against the German base of Zeebrugge andthe WWII commando attack on the Normandie Dock at St. Nazaire. Figures 4 and 5 show the maps which I drew for the games.

The scenarios for the two operations were intended to

combine naval miniatures with the boardgames SOLDIERS

(SPI) and KAMPFPANZER (SPI) providing the military

operations portions for the WWI and WWI I actions,

respectively. In spite of the fact that we have not played

out the scenarios, it was fun creating the maps and

researching the data. We have used the maps on several

occasions for window-dressing during demonstrations and

for partial games involving only the ship actions.

The scenarios for the two operations were intended to

combine naval miniatures with the boardgames SOLDIERS

(SPI) and KAMPFPANZER (SPI) providing the military

operations portions for the WWI and WWI I actions,

respectively. In spite of the fact that we have not played

out the scenarios, it was fun creating the maps and

researching the data. We have used the maps on several

occasions for window-dressing during demonstrations and

for partial games involving only the ship actions.

The map for the St. Nazaire raid uses two different

scales. The outer harbor position is drawn in the normal

scale for the GENERAL QUARTERS rules (4" per 1000

yards). The scale is changed to the 1:2400 ratio of the

ship models so that the HMS Cambeltown (with the bow

packed with explosives) can be rammed into a dry dock of

the proper proportions. The hex size used in the map

corresponds to the 100 yards per hex scale of the

boardgame KAMPFPANZER.

The map for the St. Nazaire raid uses two different

scales. The outer harbor position is drawn in the normal

scale for the GENERAL QUARTERS rules (4" per 1000

yards). The scale is changed to the 1:2400 ratio of the

ship models so that the HMS Cambeltown (with the bow

packed with explosives) can be rammed into a dry dock of

the proper proportions. The hex size used in the map

corresponds to the 100 yards per hex scale of the

boardgame KAMPFPANZER.

CHANCE AND COMMUNITY CHEST

What does MONOPOLY have to do with wargaming? Well, the idea behind the Chance and Community Chest cards (as well as event cards in KINGMAKER and other board games) is to provide surprise and require the player to react to unanticipated occurances. The intention of introducing the events is to produce minor perturbations in the game, but not to upset the basic balance.

Rather than draw a card each game turn . . . Which we might forget to do . . . we crank the winder of a kitchen timer (by not looking at it) and put the timer under the table. Whenever the gong goes off on the timer the phasing player draws an event card. Since the events operate on the phasing player, there is a certain amount of incentive to execute operations in a businesslike manner. In some steps where the resolution of damage or other procedures require the joint participation of both players, the operation of the event trigger is suspended by mutual agreement.

Note that about two-thirds of the cards in our deck are blanks so that only two or three events will occur during a game. Before the scenario starts each ship is given a unit identification number which is sometimes used to determine which vessel is affected. In other cases the selection of the unit may be left up to the player or prescribed by other circumstances.

The following examples illustrate some of the casualties which might be invoked:

-

1. Roll die for ship number. If unit has been hit by

penetrating gunfire, then ammunition handling

equipment has been damaged. Reduce port or stbd

secondary battery to one-half strength for remainder of

game. Odd roll = port; Even roll = stbd.

2. Two fighter or fighter/bomber units must be sent to provide air cover for off-board units and may not return this game.

3. Release 1 DD to conduct ASW attack off board. Your choice of unit but must have at least two hull boxes and leave scene by nearest edge. May not return this game.

4. Roll die for ship number. Communications foulup; Unit must maintain straight course at present speed next turn.

5. Roll die for ship number. Boiler casualty. Reduce speed by two hull boxes for remainder of this game.

6 Roll six-sided die. Remove this many air units, your choice, for remainder of game. (Units will be available in addition to normal replacement for next scenario.)

7 Roll die for ship number. Steering engine malfunction. Unit must circle to port for the next two turns.

8. Roll die for ship number. Ship closest to this number which still has unfired torpedoes has "hot torpedo" in one mount. That mount may not be fired during this game.

Of course, all of the events do not necessarily have to be adverse circumstances as described above. Some of the cards could be used to bring on an additional ship unit or additional air units which were not provided in the basic scenario. I hope that some of the ideas and suggestions in this article may provide additional sparkle and interest to your games.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. III #1

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1981 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com