Naval wargaming received a considerable amount of

attention and publicity during World War II. The well known

military analyst and author, Fletcher Pratt published a set

of rules which still provide the basis for several popular

game systems. POPULAR SCIENCE magazine published

plans for a number of contemporary United States naval

ships in 1:1200 scale in a series of articles which

appeared during 1939.

Naval wargaming received a considerable amount of

attention and publicity during World War II. The well known

military analyst and author, Fletcher Pratt published a set

of rules which still provide the basis for several popular

game systems. POPULAR SCIENCE magazine published

plans for a number of contemporary United States naval

ships in 1:1200 scale in a series of articles which

appeared during 1939.

Norman Bel Geddes, an industrial designer and photographer, had a fleet of more than fifteen hundred warships of all nations built to a scale of 1:1200. Geddes' ships were featured in articles in LIFE, POPULAR SCIENCE and other magazines and Sunday supplements where the models were frequently posed to illustrate naval engagements in the news. The armed forces used 1:1200 models for training personnel how to recognize and identify naval vessels. Pratt's rules and surplus recognition models provided the basis for an expanded interest in modern naval wargaming subsequent to World War II. In this article I will discuss some of the basic information relating to naval wargaming in the twentieth century period.

GETTING STARTED

There are two basic game systems used for twentieth century naval wargaming: range estimation and probabilistic. The range estimation system (publicized by Fletcher Pratt) requires the players to estimate ranges between ships as the basis for deciding whether hits and casualties are produced. Players take pride in their capability to develop and improve the skill which is r~ quired to estimate distances and to judge where the enemy targets will be at the end of the movement phase. Thus, the players attempt to solve a game analog of the fire control problem, all be it without the rangefinding and computing equipment of the modern warship.

The probabilistic game system uses dice rolls and some kind of Combat Results Table(s) to determine hits and damage in much the same manner as board wargames and other miniatures wargames. The table in this article list the various rules which are available and indicate which basic game system is used by a particular set of rules. Some rules are complete game systems which provide rules of play, ship data and various play aids.

Other sets of rules require research of ship data, calculation of ship cards, etc. before one is ready to wargame. Many naval buffs enjoy researching and calculating the data which are necessary to play a game. If you are primarily interested in gaming, be sure that the rules which you select have a reasonably extensive set of ship characteristics available, either as an integral part of the rules or for purchase as an accessory booklet. The tables in this article give some indication of the relative completeness of each set of rules.

In looking for a set of rules to get started, therefore, one has to decide on which basic game system appears to be the most challenging, and to keep an eye out for the relative completeness or thoroughness of a particular set of rules.

BOOKS ABOUT NAVAL WARGAMING

There are four books from which one can learn more about naval miniatures and wargaming. NAVAL WAR GAMES by Donald Featherstone (Stanley Paul, London, 1965) is the oldest, but still the best and most complete treatment of naval wargaming. Featherstone covers all periods in history and includes several sets of rules for different eras. His book also includes a reprint of Fred Janes' rules of 1989 and a reprint of Fletcher Pratt's rules of the 1940's.

A more recent book, SEA BATTLES IN MINIATURE by Paul Hague(Patrick Stephens Ltd., Cambridge, 1980) provides an excellent overview of naval wargaming of all periods in history and includes rules as well as instructions for making models.

SEA BATTLE GAMES by P. Dunn (MAP Ltd., 1970) includes sailing ship rules and twentieth century naval rules as well as information about the purchase and construction of models. Dunn's book is somewhat less comprehensive than Featherstone or Hague.

NAVAL WARGAMES by Barry Carter (ARCO, 1975) concentrates on the twentieth century period and includes some information about naval board wargames. All of the books mentioned are well iF lustrated with photographs, maps and sketches to provide the reader with a visual impression of the excitement and interest to be found in naval miniatures.

MODELS OR MOCKUPS . . . WHAT SCALE?

Although most rules mention a particular size scale as appropriate, most rules can be used with ship models of any scale. Very few rule systems use a game scale which is the same distance scale as the ship model size scale. Those rules which do specify a distance scale identical with the model scale generally require a gymnasium, ballroom or parking lot to provide sufficient area for a playing surface.

Cast plastic or metal models are commercially available in scales of 1:1200, 1:2400, 1:3000 and 1:4800. Stated in other terms, the above scales mean . . . 1" = 100 feet; 1" = 200 feet; 1" = 250 feet; or 1" = 400 feet; respectively. The 1:3000 scale can also be interpreted as

1 mm = 10 feet, or 1 cm = 100 feet. Those who may wish to make models can find ready-made measuring scales available by purchasing and "Engineer's Scale" at a drafting supply store.

Cast plastic or metal models are commercially available in scales of 1:1200, 1:2400, 1:3000 and 1:4800. Stated in other terms, the above scales mean . . . 1" = 100 feet; 1" = 200 feet; 1" = 250 feet; or 1" = 400 feet; respectively. The 1:3000 scale can also be interpreted as

1 mm = 10 feet, or 1 cm = 100 feet. Those who may wish to make models can find ready-made measuring scales available by purchasing and "Engineer's Scale" at a drafting supply store.

Cost will be a primary consideration in determining what scale is likely to be feasible for a gamer. A battleship, 750 feet long (7 1/2" model size) in 1:1200 scale may cost $10-$15, depending on the particular ship and manufacturer. Destroyers, about 3" long in 1:1200 scale, may cost $3-$5 each. In general, the 1:2400 models, which would be one-half of the size quoted for the :1200 scale, would cost only about one-third or onefourth as much as the 1:1200 models. The small end of the size and price spectrum is the 1:4800 scale, where one can obtain a set of ten ships for about $5; but, the largest ship is less than two inches long.

Cardboard silhouettes or plan views (generally in 1:1200 scale) can be purchased from some sources or made from plans in naval reference books such as JANE'S FIGHTING SHIPS. Cardboard counter sheets for the boardgames JUTLAND, SUBMARINE or BISMARCK can be purchased from the Avalon Hill company spare parts list to provide "professional-looking" markers. The boardgames can often be purchased at flea markets or club auctions and used for parts. Model makers can use balsa wood or soft pine to build reasonably realistic 1:1200 scale ships from the plans in JANES or other naval annuals. The reference books cited in the previous section provide helpful advice for modelers. JANE'S FIGHTING SHIPS is an excellent source of plans (1:1200) and pictures for model builders as well as ship data for those who wish to calculate their own ship data cards.

However, at $125 per year, it is about as unattainable for an individual as it was for me in 1940 when the annual volume cost was only $25. I used to bring my lunch to the Grosvenor Library in Buffalo to browse through the only set available to the city. Later, in Washington, D.C., I repeated the treks on weekends to the Library of Congress. In recent years the U.S. Naomi Institute has been publishing COMBAT FLEETS OF THE WORLD, edited by Jean L. Couhat. The price of $65 for the 1980/81 volume is only half that of JANES. but it will still put a sizeable dent in a naval buff's budget. ARCO publishers have reprinted several volumes of JANES: 1898 (the first issuer 1905/06, 1906/07, 1914 and 1919. The volumes are available at prices ranging from $15 to $25 depending on the volume and the supplier.

For someone who is just getting started, a consumer's "best buy" is THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE WORLD'S WARSHIPS, by Hugh Lyon (Crescent Books, 1978). This book contains selected ship statistics and pictures for naval ships from 1900 to the present and can be purchased for about $13. There are colored photographs and plates which give excellent details for constructing and painting models.

NAVAL WARGAMING RULES

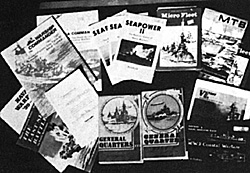

The tables accompanying this article list rules for

twentieth century naval wargaming. Most of the rules listed

are still available in the original edition, as a reprint (e.g.,

Fletcher Pratt), or in a revised edition. One table lists

rules using the range estimation system. The other table

lists rules using a probabilistic hit/damage system. I have

played both types of rules, starting with Fletcher Pratt in

1942 and prefer a probabilistic system.

The tables accompanying this article list rules for

twentieth century naval wargaming. Most of the rules listed

are still available in the original edition, as a reprint (e.g.,

Fletcher Pratt), or in a revised edition. One table lists

rules using the range estimation system. The other table

lists rules using a probabilistic hit/damage system. I have

played both types of rules, starting with Fletcher Pratt in

1942 and prefer a probabilistic system.

The resolution of gunfire is generally a two-step procedure. First, it is required to decide whether the target has been hit; then the type of damage is determined. As a part of the primary considerations above one also ascertains whether the target is in range, whether armor has been penetrated and where the target has been hit, either as a part of the two-step procedure or in separate calculations or table entries. Many of the rules are quite complex and require numerous die rolls and/or the use of various auxiliary tables to resolve the combat procedure. Some players equate complexity and detail with "realism". However, the use of detail is not necessarily any more realistic than some simpler technique. The MTB and WWII COASTAL rules listed in the tables involve considerable detail and use a very short time interval per game turn. Such short game turns lead to what I "bionic commander" syndrome where real time is cut into so many small chunks that players may ponder and analyze actions which would not be feasible in 'real time'.

Many players would prefer more action and less bookkeeping. In general, the less complex rule systems permit games to be played to completion in shorter time periods than the other, more detailed rules systems. I have given each of the rules a complexity rating of 1-5, with 1 being the simplest and 5 being the most difficult. Complexity can take several forms. One type is simply the requirement to perform a lot of tasks to complete a procedure, but each of the tasks may be easy to implement. Complexity can also mean that convoluted procedures are required such as calculations or complicated table-indexing.

Another form of complexity may arise from a lack of clarity in the writing of the rules so that the players do really understand what is required to implement a procedure. The lack of clarity in some rules arises from the fact that the rules were written for persons who are generally familiar with miniatures rule systems and were not written for neophytes or novices. Many sets of rules could be improved by the addition of diagrams to explain how procedures are implemented.

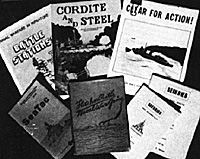

I remarked in the section on getting started that some sets of rules are more complete than others. GENERAL QUARTERS (either version by itself), PANZERSCHtFFES, SEA POWER, SEKRIEC and SEATAC are complete and ready-to-go. All of these rules are reasonably simple and/or well-documented with examples and illustrations so that a novice could probably figure out how to play. MTB, MICRO FLEET WWI and MICRO FLEET WWII, which are all published by Tabletop Games, are complete and even include cardboard ship markers in the package.

However, these rules are rather complex for a

beginner. BATTLE STATIONS, CLEAR FOR ACTION,

CORDITE & STEEL and WARSHIP COMMANDER are

complete and ready-to-play, but probably require some

previous experience because of the complexity of the

game systems. The other sets of rules generally do not

include the ship data which are necessary to play the

game. Rules which have a section on campaigns or

strategic rules are desireable to provide an overall rationale

for engagements which might take place.

However, these rules are rather complex for a

beginner. BATTLE STATIONS, CLEAR FOR ACTION,

CORDITE & STEEL and WARSHIP COMMANDER are

complete and ready-to-play, but probably require some

previous experience because of the complexity of the

game systems. The other sets of rules generally do not

include the ship data which are necessary to play the

game. Rules which have a section on campaigns or

strategic rules are desireable to provide an overall rationale

for engagements which might take place.

Otherwise games tend to be power-dominated slugfests on a Saturday afternoon with no overall pattern or motive other than to "do in" the enemy. The best and most complete strategic rules suggestions can be found in GENERAL QUARTERS and SEEKRIEG. The reference books cited in the previous section also discuss campaign rules.

ADDITIONAL EQUIPMENT

Most of the rulebooks suggest additional equipment which may be required for gaming. The three basic components are the rulebook, models or markers, and ship data in a form useable in the game. A tape measure and dice (either conventional or decimal) are usually sufficient to implement most sets of rules. The price of SEA POWER and PANZERSCHIFFES rules includes a set of special dice which are used with those games. I recommended getting a tape measure with dual units (inches and centimeters) regardless of the rules selected.

Dual tapes do not usually cost much more, and almost any set of rules can be played in one-half the area by substituting centimeters wherever the rules call for inches. Most sets of rules include speed (movement) scales, turn templates and other miscellaneous equipment which can be cut out or Xeroxed. Poker chips, golf tees, cotton balls or boardgame counters can be used to mark gunfire, shell splashes, smoke screens or for other special effects.

PROBALISTIC SYSTEM RULES

I use 1:2400 and 1:3000 scale models for my naval wargaming. I prefer to mount each model on a piece of cardboard. Mounting prevents the relatively unstable models from being tipped over. The stand also provides a convenient handling device to reduce rubbing and wear of the painted surfaces on the model. By using a blue colored card and marking in white ripples for a bow wave and wake, I also have a somewhat more lifelike appearance. I use two sizes of mounting cards. A stand 0.8" x 3.1" serves for 1:3000 battleships or 1:2400 cruisers. A 0.8. x 2.6" mount can be used for 1:3000 cruisers or 1:2400 destroyers.

Battleships in 1:2400 scale will need a card about four inches long. I use a common width for the mounts because I have a carrying case with rails in which I can slide the mounting cards to prevent the models from sliding about. On the destroyer cards I put a one-fourth inch cube of balsa wood at the front, left corner. The cube serves as a handle to pick up these small models; however, the main purpose is to provide a place where flotilla or squadron flags can be placed. We also use map pins in the blocks to indicate a particular type of sensor capability such as radar or sonar. The presence of the mounting cards also inhibits the players from moving units unrealistically close to each other.

REFEREES

Several of the rule systems which I have indicated as be ing complex were written on the premise that a referee or team of referees would be used to resolve combat and adjudicate other matters. In fact, some of the game systems are so complicated that experienced referees are a necessity to execute the various procedures, keep track of the bookkeeping, etc., thus freeing the players ~ to maneuver and fight their vessels. The rules rated at a I complexity level of 1 or 2 (and, perhaps 3) can probably be implemented without requiring the services of referees. The various boardgame rules discussed in the next section could also be used as miniatures rules without requiring the services of a referee.

CONCLUSIONS

There are no bad rules for naval miniatures. All of the game systems evolved over a period of time and were playtested before the rules were ultimately edited and published. Some rules are simpler, some more complex than others. Some were written with clarity and include worked out examples and illustrations; others are terse and sparsely documented.

Aficionados will find unique and interesting features in each of the game systems listed in the tables. One of the virtues of starting with a simple game system is that one can add nuances of his own without bogging down an already complex system.

Many individuals and groups still use rules which are very close to those of Fletcher Pratt. Persons who entered the naval miniatures hobby in the early 1970's still use SEA POWER or VICTORY A T SEA as the basis for their games because of the utility of those systems. Newer gamers have often adopted the PANZERSCHIFFES or GENERAL QUARTERS rules as easier ways to get started. Older gamers have tended to stay with their original choice of rules since the new rules did not seem to represent "a great leap forward", at least to one who had mastered the older system. At the annual ORIGINS convention in the summer of 1980, in voting for the H.G. Wells Awards, gamers voted GENERAL QUARTERS as the "All Time Best 20th Century Naval Rules".

NEW NAVAL EDITOR

CLIFFORD L. SAYRE JR.

Cliff's interest in the navy and naval history started at an early age during a vacation visit to the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland. He was particularly intrigued bY a series of articles in POPULAR SCIENCE magazine in 1939 which provided sets of 1:1200 plans for United States naval ships. Cliff's initiation into naval wargaming occurred in 1940 when his father gave him a co" of Fletcher Pratt's naval rules. This led to many weekends of gaminy in the local highschool, using a large floor area outside of the library. He attended the Navy V-12 Program and R.O.T.C. at Duke University and was commissioned an ensign in 1947.

Wargaming activities faded into the background during two years of sea duty aboard the U.S.S. HOBSON (DMS-26), shore duty at the David Taylor Model Basin during the Korean War, marriage, children, more eoucation, etc. Since bieng placed on active duty from the Navy he has been on the faculty of the College of Engineering at the University of Maryland. His interest in wargaming was renewed by a copy of the Avalon Hill boardgame, JUTLAND, in 1970. He subscribed to some of the board gaming magazines, joined some local wargaming clubs, wrote articles or reviews for a number of magazines such as SIGNAL, EUROPA, FIRE & MOVEMENT, JAGDPANTHER, PANZERFAUST, MOVES, etc. and generally reentered the wargaming scene. Cliff helped to initiate the Charles Roberts Awards in Baltimore at ORIGINS I and has participated in most of the ORIGINS conventions. Over the past few years his interests have shifted from boardgaming back to naval miniatures. During ORIGINS '79 and '80 he conducted several seminars or demonstrations about various aspects of naval boardgaming and naval miniatures.

Cliff is presently very active on the Awards Committee of the Academy of Adventure Gaming Arts and Design.

Naval Rules Compedium (Tables)

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. 2 #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1981 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com