We hope that this article will provide you with a brief

outline to an often neglected period of warfare. In it we will

attempt to relate a short history of the wars, the armies

involved in the conflict, and deal with this information

transformation to the wargames table.

We hope that this article will provide you with a brief

outline to an often neglected period of warfare. In it we will

attempt to relate a short history of the wars, the armies

involved in the conflict, and deal with this information

transformation to the wargames table.

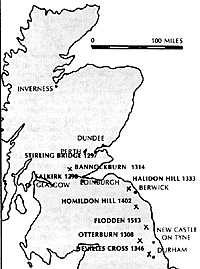

The Scots-English was was a bitter struggle that lasted throughout the Medieval period. It began with the attempt of Edward 1st, of England, to unite Scotland with England, as he had done with Wales. However after uprisings led by Sir William Wallace (Stirling Bridge 1297 and Falkirk 1298) and Robert Bruce (Bannockburn 1314) a somewhat unified nation of Scotland with an independent national identity was re-established.

After this the Scots succeeded in recapturing Berwick which had been torched and sacked by Edward 1st and then began sending major raids into the north of England as far south as Yorkshire. In 1322, England, under Edward II, again tried to subdue Scotland but a scorched earth policy by the Scots forced his defeat and withdrawal to England. With the death of Robert Bruce (1329) Scotland was plunged into civil war by the governing regency.

The Balliol faction of the regency, with the support of Edward III of England, gained nominal control by invading Scotland from the north of England (Halidon Hill 1333). Although this brought some measure of stability to the government, it did not stop the successful raiding of northern England by the Scots. With French support, David II, the exiled king returned to Scotland to displace the Balliols and while Edward III was occupied with affairs on the continent (Crecy 1346), invaded the north of England (Nevilles Cross 1346).

After this defeat the "Black Death" brought a halt to the conflict between the nations and it was not until 1355 that the Scots were to invade England again; once again it was to support the French. With the Scots defeat the capture of David II, and the defeat of the French (Poitiers 1356) the conflict became one of border warfare which lasted until the turn of the century.

This warfare was mainly of a minor nature which included: The town of Roxburgh ravaged and burned (1371);Berwick captured by Scots (1378) and lost again; Scarborough town plundered by a combined French, Spanish and Scots fleet which in turn was destroyed by an English fleet; border raids (Otterburn 1338), and clan feuds in Scotland.

In 1399 Henry IV came to the throne of England and his attempts to stop the raids proved futile until a retiring Scots raiding force was caught and defeated (Homildon Hill 1402). Following this there was no major conflict for over 100 years, although the border warfare continued. The Scots were involved with France on the continent and the Wars of the Roses at home. The final involvement in the conflict came with James IV's attempt to aid France in her war with England. His invasion of England ended in his defeat and death (Flodden 1513).

Stirling Bridge: The English army was unable

to deploy and support the cavalry charges: they were

trapped by the terrain and destroyed.

Stirling Bridge: The English army was unable

to deploy and support the cavalry charges: they were

trapped by the terrain and destroyed.

Falkirk 1298: The English archers

decimated the Scots spearmen. Then the cavalry, after

dispersing the Scots achers, charged and broke the Scots

formations

Bannockburn 1314: The terrain hampers

the deployment of the English army. Their cavalry was

destroyed trying to break the Scots formations without

sufficient support from the foot.

Dupplin Muir 1332: Dismounted English

knights supported by archers on their flanks destroyed the

Scots spear columns once they had become disordered.

Halidon Hill 1333: Archers, supported by

dismounted men at arms, disrupted the Scots spear

columns which were then swept away by the mounted

knights charge.

Nevilles Cross 1346: English archers

supported by dismounted men at arms defeated the Scots

who were constricted by the terrain. The disorganized pike

was swept away by cavalry charges.

Otterburn 1388: A night attack by the

English on a retiring Scots army turned into disaster when

the Scots counter attack turned the English flank.

Homildon Hill 1402: The Scots were

maneuvered out of a strong position by archery fire and

were skirmished into making ineffectual attacks which

were defeated and dispersed by the English.

Flodden 1513: The Scots with superior

weapons and position were maneuvered into unsuitable

terrain where disordered and confused the pike formations

were de,feated by the English knights.

Most of the conflict of this period took place in the border region between Scotland and England. It was an area constantly ravaged, if not by the armies then by the raiding of the large border families, both English and Scot. Most battles of this time resulted in the almost total destruction of the defeated army; the Nobles were held for ransom and the lesser men pursued until their units were destroyed and the men dispersed. The conflict evolved as a war between two diametrically opposed armies; the Scots, a pole arm based infantry army versus the mounted and missle supported army of the English.

The armies of this time utilized the basic feudal system. The main elements of the feudal system were the knight (fully armoured and mounted on a heavy charger), men at arms (less heavily armed but mounted sons of knights and younger brothers) and freeholders (on foot).

Added to these were the various mercenaries (professional soldiers, subsidized allies and household knights) and the levy; the king had the right to call all able bodied men to serve (aged from 16 to 60). This system had much less influence on the Scots as it was only really developed in the southern part of the country.

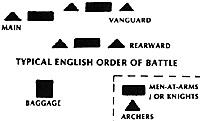

On the battlefield these forces were organized into various size units, referred to as battles, each of which was commanded by a knight of Baronial rank or higher. At Bannockburn the English knights were organized into 10 battles of approximately three hundred men each. The army itself was usually divided into three large battle groups.

These divisions were referred to as the Vanguard, the Main and the Rearward battles and all march and battle order was derived from these. In battle the Vanguard formed the right wing of the army, the Main formed the centre while the Rearward battle constituted the ieft wing or in constricting terrain it would often form the reserve (fig. 2). These larger divisions could always be broken up into smaller units.

ENGLISH ARMY

The strength of the English army lay with their

mounted arm which, when properly supported by archers,

would ensure victory. The majority of the cavalry would

consist of the heavily armoured knights and the men-at-

arms. At the beginning of this period they would be quite

numerous, however their numbers and importance

declined with the increased use of the longbow. The

majority of the knights were dressed in full mail armor

while the wealthier and more important knights added an

armoured breastplate. Many of the knights would also

wear a coat of plates (actually a surcoat lined with small

iron plates usually fastened to the material by rivets).

The strength of the English army lay with their

mounted arm which, when properly supported by archers,

would ensure victory. The majority of the cavalry would

consist of the heavily armoured knights and the men-at-

arms. At the beginning of this period they would be quite

numerous, however their numbers and importance

declined with the increased use of the longbow. The

majority of the knights were dressed in full mail armor

while the wealthier and more important knights added an

armoured breastplate. Many of the knights would also

wear a coat of plates (actually a surcoat lined with small

iron plates usually fastened to the material by rivets).

The decrease in the use of the mounted arm saw them dressed in more and more plate armour which greatly reduced their mobility. Their legs were generally covered by mail although closed, armoured greaves were also known to have been employed. Their headwear consisted of a wide variety of helmets varying from kettle helmets and flat topped barrel types helms, to the more modern ones with the top being more conical than flat, which would be adorned with crests, usually constructed of parchment, whalebone, painted wood or paper mache.

While mounted, the knights and Men at arms usually employed a light lance which later developed into a much heavier weapon as the weight of the armour also increased over the period. Their secondary weapons consisted of the usual medeival variety of sidearms - axes, maces and swords. They later showed a distinct preference for the long slashing sword, with a 37" to 40" blade which would be swung with both hands when dismounted.

The English mounts were chargers bred for fighting; and they were usually barded. This barding consisted of quilted or mail armour worn under the horses trappings, a coloured surcoat which displayed the coat of arms of the knights or individual house. Added to this barding was some plate armour introduced by some of the more affluent nobles and also a chanfrou or iron headpiece to offer some protection to the horses head.

The English Kings, beginning with Edward I, were strong believers in the use of mercenaries, not only to supplement the English troops but as often as not to replace them altogether. Outside of their weapon capabilities, i.e. the Welsh with their longbows, these troops were generally more reliable than the English feudal levies which were called up to support the heavy mounted troops. The levy cavalry were generally light or medium cavalry, the famed border horse or moss troopers. They were very useful for scouting, raiding and skirmishing but could not be relied upon to stand and fight in a set battle.

These formed a relatively small part of any English army being much more suited to the Scots spirit and their terrain. The levy infantry and the various mercenaries (be they Welsh, Irish, Spanish, Gascons, etc.) were generally lightly armoured. The spearmen raised in the north countries and Wales would be equiped generally with a quilted jacket and in some cases mail, (usually obtained from a previous battlefield), a very light helmet, the kettle type being the nost popular, and sometimes with a small hide shield. The levy archers first raised in Wales and then throughout the north western counties, were usually unarmoured and relied on their archery to stop the enemy from closing with them. Few of these troops wore uniforms of any kind however the Welsh have been recorded at various times in either red or white tunics.

The composition of the English armies varied considerably throughout the period although they still maintained the principle of the cavalry for power supported by the archers. With the increased effectiveness of the longbow, the number of archers grew to an impressive 75% of the army by the close of the wars.

As their importance increased adjustments had to be made to the armies tactics and fairly regularly the men-at- arms were used exclusively for their protection. They were usually dismounted and placed between the various archer formations.

Periodically the English knights would fight dismounted, however this was not a frequent happening as the knights were difficult to control and quite often acted independently and insubordinately. Their most effective ues was as a shock weapon and when properly supported by the missile power of the longbow provided a decided advantage over the enemy.

SCOTS ARMY

Scots armies of this period were traditionally infantry armies supported by small units of knights. The Scots drew their strength mainly from the lowlands of Fife (ScotsPicts) Galloway (Gallgaels), Lothians and the borders, Maray and Ross and the area of Carrick. These provided the traditional military levies of the earldoms and were usually led by its own earl or other high ranking nobility. These provided the usual bulk of the Scots forces. These levies were comprised mainly of poorly equipped farmers and land tenants, seldom provided with more than a spear, short tunic and a cloak. Many were even more scantily dressed, with only a hooded cape, and there was a predominance of both bare legs and bare feet.

The main armament of this levy force was a 10' to 12' spear which was used in a close formation. This spear with its small head, was in effect an early example of the renaissance pike. Secondary weapons of the infantry consisted mainly of axes, knives, and javelins. They were usually equipped with a fairly small shield, quite often made of cowhide, known as a targe or buckler. Few, if any of the levy were equipped with plate armour or helmets, rather their tunics were rough hide and homespun cloth and for protection they relied on leather coats and quilted tunics.

The colours of the various garments was restricted to the various dyes available and were limited to various greens, browns, dull reds, yellows or unbleached cloth. Bright reds, and purples were very expensive and used only by the wealthy. The tartan at this time was merely a brightly coloured woolen cloth which could be spotted, striped or patterned.

Smaller contingents of foot were also provided by the levy of the Ettrick forest area which had the only effective at close range. When it served their own particular purpose the army could draw contingents of levies from the Islesmen and Gaels (Highlanders), however these were more often at odds with the Scots crown and in league with the English. These men of the Isles, Argyle and highlands with their two handed long swords and lochaber axes (descended-from the gisarme) were an undisciplined group who would be depended upon to deliver a wild charge but were easily dispersed if things did not go as desired.

Cavalry, always a weak arm for the Scots, consisted of knights and men-at-arms, both of whom habitually fought on foot, and lightly armed horse drawn from the border regions. The Norman style of feudalism only really took hold in the south of Scotland with the resulting small portion of men trained as heavy knights and truly capable of this method of combat. The heavy cavalry clearly resembled their English counterparts with helms, skirted harness, bannered lances shields and horses barded in steel or lined.

However by dismounting and fighting on foot what they lost in mobility was gained in the increased morale strength of the army. Their horses, shaggy ponies and smaller breeds, had no chance when forced to stand up to the weight of the chargers employed by the English. The border cavalry, lightly armed and highly mobile, made superb use of the small ponies and armed with spear, sword and small shield were constantly engaged in raiding across the border. This type of warfare appealed to the Scots more than the English.

The Scots army was a potentially strong army which unlike its Swiss counterpart never achieved its full potential. It was continually humiliated on the battlefield because it lacked leadership and the proper motivation. In the schilton it had developed a powerful and cohesive element which should have had the advantage over the levy spearmen of the English.

These bodies of spearmen, although lacking in mobility and manoeuvreability for a strong offensive threat, were ideally suited to the defensive and achieved varying degrees of success against the English. When used in conjunction with cavalry and or light missile troops and with the advantages of defensive terrain they were invaluable. However they suffered drastically when not preceeded and supported by light or mounted troops or when having lost their order through casualties or terrain. They were rarely a force strong enough to decide a battle on their own.

In warfare the Scots ignored all of the rules of chivalry employed by the English. This along with their extensive use of the terrain, steep hills, swampy ground, and defensive weapons severely restricted the battlefields and constantly hampered the English deployments and battle formations.

WARGAMING WITH MEDIEVALS

It is not difficult to transform the medieval wars of the English Scots onto the wargames table. We hope that the following will demonstrate our own interpretation of this time period. From the research conducted, W.R.G. style army lists were established for both of the armies.

SCOTS

General mounted on horse or on foot @ 100 pts. 1

Border hone irregular D LC or MC5 to 30 light lance & shield @ 5 pts.

extra to upgrade to C @ 1 pt. or B @ 2 pts. any or all

extra to give xbow @1 pt. any or all

Knights irregular B EHI long spear or two handed cutting weapon and shield @ 10 pts. up to 18

Men at-arms: irregular C HI long spear or two handed cutting weapon & shield @ 5 pts.up to 18

Infantry irregular D ML long spear & shield @ 3 pts. 100 to 250

extra to make C class @1 pt.any or all

Highlanders irregular D LI sword & shield @ 2 pts. up to 65

extra to give bow @ 1 pt. up to 30

extra to give two handed cutting weapon @ 1 pt. up to 40

extra to upgrade to C @1 pt.up to 65

extra to upgrade to A @ 3 pts. up to 15

Peasants irregular D LMI/LI two handed cutting weapons or javelins @ 1 pt.up to 100

up to 12 irregular command factors @ 25 pts.

Note if EHI or HI used then it must be front rank of unit or not at all; up to 40 LI highlanders may be LMI

ENGLISH

General: mounted on horse or on foot @100pts 1

Knights irregular A EHC heavy lance, two handed cutting weapon & shield @13 pts. 20 to 45

Men at Arms: irregular C HC light lance, two handed cutting weapon & shield @ 9 pts. 20 to 45

Border horse irregular D LC/MC light lance & shield @5 pts. 5 to 30

extra to upgrade to c class @1 pt. any or all

extra to give xbow @1 pt. any or all

Infantry: regular D MI long spear or short spear @ 3 pts. up to 30

regular D MI two handed cutting weapon @ 3 pts. up to 30

regular D LMI or LI crossbow @ 2 pts. up to 10

regular D LMI or LI longbow @ 2 pts. 40 to 100

irregular c LI javelins @ 2 pts.up to 15

extra to convert MI to HI @ 2 pts. up to 30

extra to upgrade from D to C class @ 1 pt. up to 100

Peasant irregular D LMI long spears @1 pt. up to 50

up to 6 regular command factors @ 10 pts.

up to 10 irregular command factors @ 25 pts.

These lists were not intended to be absolutely final and are subject to constant revision with new information.

Although there are various sets of commercial rules available, dealing with the medieval period, for our own personal use we have modified the W.R.G. Ancients (5th ed.) to suit. The various adjustments that we have made to the rules are:

- 2 casualties per figure of a unit by archery fire causes disorder for that period.

- Extra heavy infantry: a classification for dismounted knights involving fighting as super heavy infantry and movement as per heavy infantry.

- Longbow fire is +1 on the archery fire factor and uses the crossbow ranges.

- Mixed units receive casualties from missile fire at the majority's classification.

- Mixed units test 1st reaction at the highest classification.

- Irregular long spears fight at 1% ranks deep.

- Knights and men-at-arms may instead fight on foot, HC as HI and EHC as EHI with either a long spear or a two-handed cutting weapon and shield.

Medieval Warfare: A Sample Game

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. 2 #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1981 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com