Montenegro (Crna Gora, the Black Mountain) was an inland section of Serbia that survived the fall of its parent state to the Ottoman Turks. The country maintained a tenuous connection with the West via the Dalmatian coast holdings of Venice. After 1715 Russia exerted a vague benign influence. However it was not until the Napoleonic Wars that Montenegro really came to Western notice. At various times the Russians, Austrians, and British courted mountaineer aid to throw the French out of Dalmatia, and even undertook several combined operations.

Montenegro (Crna Gora, the Black Mountain) was an inland section of Serbia that survived the fall of its parent state to the Ottoman Turks. The country maintained a tenuous connection with the West via the Dalmatian coast holdings of Venice. After 1715 Russia exerted a vague benign influence. However it was not until the Napoleonic Wars that Montenegro really came to Western notice. At various times the Russians, Austrians, and British courted mountaineer aid to throw the French out of Dalmatia, and even undertook several combined operations.

After 1697, Montenegro was ruled by a VLADIKA, or hereditary prince bishop. Countless wars created a culture which glorified combat, courage, and the unrelenting struggle against the Turk. Every male adult was considered fit to fight, and the term "adult" was so losely defined that some mountaineers had seen fifty years of combat.

The Montenegrins fought and were ruled in a clan structure. Family households were grouped into CELA averaging 10~120 fighting men. From 2-10 CELA then formed a PLEME or tribe, which was the basic social and military unit (there was a larger grouping of little effectiveness, the Nahia or district). Every PLEME had its own banner.

On the plains, the Montenegrins had trouble with regular volleys, cavalry, and artillery, for which they entertained an almost superstitious fear. The tribesmen also lacked staying power for sieges. Many would drift away from the lines when bored or hungry.

However, in their own mountains the Montenegrins were well nigh invincible. During the Napoleonic wars they regularly wiped out French voltigeur outposts. The tribesmen were all marksmen in shooting and savage in melee. They were masters of the cunning ambush, the quick raid, or the heroic stand in a wellplaced fort. Since an army's commissariat was supplied by what the men or their wives could carry, the Montenegrins had amazing mobility.

They dispensed with roads, indeed discouraged their construction. The country did have a few cannon in forts. Except for the chiefs and the VLADIKA'S bodyguard no one ever went mounted. As late as 1614 some Montenegrins were reported using crossbows. By the 18th century the tribes had adopted long muskets, some richly inlaid with pearl. These were supplemented by several pistols stuck in a waist sash and wicked-looking long knives known as yataghans.

From long years as a Christian island in a Moslem sea the Montenegrins had become incredibly ferocious in battle. Head taking was a time-honored custom, the measure of a man's pride and worth. "It was a terrible spectacle," wrote a Russian officer in 1806, "to see the Montenegrins rushing forwards, with the heads of slaughtered enemies suspended from their necks and shoulders, and uttering savage yells."

The mountaineers had no uniform, but did wear a fairly standard national dress. This consisted of white shirt; red sleeveless vest with black and gold embroidery; multi-colored waist sash; dark blue zouavetype trousers; white stockings; and brown pointed native shoes. Depending on the weather, there might be thrown over this a white or yellow coat, a fur coat, or a brown national garment called a strucca, which was sort of a combination scarf, shawl, and cloak.

For a long time the headgear was a red fez or turban. However, around 1800 this was replaced by a small round cap with red top and black sides.

At least one VLADIKA was distinguished by black gloves, gold trim, and a scarlet pelisse with white fur and no frogging. His 30 to 100 bodyguards were called the PERIANIKI from the distinguishing white feather they wore in their caps.

The priests (all of whom fought) wore beards ahd mustaches; the rest of the males mustaches only. Montenegrin hair was often brown, sometimes dark brown, rarely black. Eyes were hazel or light blue.

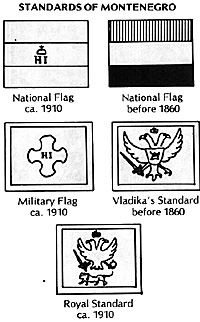

Sometime during the 19th century the mountaineers adopted a national flag. This had three horizontal stripes, blue, white, and red. Some reports placed a cross in the upper blue stripe near the pole. Dating from earlier were the VLADIKA'S personal arms. These varied slightly from ruler to ruler, but basically consisted of a red field; white double- headed eagle grasping gold ball and sceptre, above which is a gold crown; and on the eagle's chest a blue small shield bearing a gold lion, passant on green grass.

THE NATIONAL MILITIA, 1850-1915

After 1850 technical progress and Western- type organization finally made some inroads in the little state. The prince bishop became a wholly secular prince in 1852 and a king in 1910. Moreover, following a disasterous war in the 1860's, serious efforts at military reform began.

By diverse means, including a lottery in France, modern weapons were acquired. Permanent field artillery appeared for the first time -- four 4-gun mountain batteries. The men were formally enrolled and organized -- although the groupings were still tribally based. By 1877 there were two 10,00.0 man divisions of infantry, each containing two brigades, each of which had one battalion armed with needle guns and four with Minie rifles. The 8-company, 848- man battalions were the basic maneuver unit of a force that won several resounding victories in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878.

In keeping with the new, modern image, head taking was suppressed by the imposition of severe criminal penalties. However, so deep-rooted was the custom that isolated incidents were reported as late as the First World War.

In the last half of the 19th century the Montenegrins also experimented with a brigade of cavalry. However, they never had been very good horsemen, and the cavalry were disbanded in 1898.

By 1910 the army had changed somewhat. Al1 high officers had at least the rudiments of training. The amount of artillery had been upped to four howitzers, 18 siege, 25 field, and 38 mountain guns, with 15 mortars and 18 machine guns. Territorial and population increases had produced 38,000 infantry in 11 brigades, which were now the major operating units. There were 4-6 battalions per brigade, 56 battalions in all. It was estimated that 20,000 men could be concentrated in 48 hours.

When Montenegro became a kingdom in 1910, the army at long last received a uniform. The men wore a simple field gray jacket, knee- length trousers, and stockings, with black shoes and a small, round, field gray flattopped cap bearing a gold badge of rank in front. Officers had a field gray jacket, hat, and trousers of Russian cut, with black knee boots. Their hats had gold badges of rank, and gold epaulettes were worn on parade. Officers and NCO's were also distinguished by piping on their field gray shoulder tabs: red for I generals, scarlet for infantry, light blue for machine I gunners, yellow for artillerymen, and green for pioneers. The king's guard wore blue gray instead of field gray.

After Prince (later King) Nicholas I took the

throne in 1860, the country's standards were also

modified. The national flag became a horizontal

tricolor of red, blue, and white, with the center blue

stripe displaying, underneath a gold crown, Nicholas'

initials (in Cyrillic). The royal standard turned into a

white-bordered red square bearing a white

doubleheaded eagle above a white lion passant.

After Prince (later King) Nicholas I took the

throne in 1860, the country's standards were also

modified. The national flag became a horizontal

tricolor of red, blue, and white, with the center blue

stripe displaying, underneath a gold crown, Nicholas'

initials (in Cyrillic). The royal standard turned into a

white-bordered red square bearing a white

doubleheaded eagle above a white lion passant.

Above the eagle was a gold crown, and it grasped a gold ball and sceptre. On the eagle's chest were the golden initials, "Hl". Finally, Nicholas introduced a "military flag". This consisted of a white- bordered red square displaying a white, rounded Greek cross. In the center of the cross were (surprise!) the golden initials "Hl".

However, some things had not changed. The Encyclopedia Britannica of 1910 reported that "the wives and daughters of the troops provide the commissariat and carry the ammunition".

The combination of ancient fighting spirit and modern technical infusions worked well for the Montenegrins. During the Balkan Wars, they not only fought ably in battles, but also managed to undertake a long and successful siege of Scutari. Then, in World War I, the mountaineers repelled several small Austrian attacks until both Montenegrin and Serb fell to the Bulgarian backstab of 1915. After the war, the little country ended 500 years of independent existence when it was absorbed into the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

SOURCES

Denton, William. Montenegro. London,

1877.

Djilas, Milovan. Njagos: Poet, Prince,

Bishop. New York, 1966.

Durham, Mary. Through the Land of the

Serb. London, 1904.

Holbach, Maude. Dalmatia. London,

1908.

Knotel-Sieg. Handbuch der

Uniformiunde.

"Montenegro". Encyclopedia Britannica

(11th ea., 1910).

"Our Flag Issue". National Geographic,

October, 1917.

Stevenson, Francis S. A History of

Montenegro. London, 1912.

Wilkinson, J. Gardner. Dalmatia and

Montenegro. London, 1848.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. 1 #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1980 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com