The following battle was fought using my HEART OF

OAK rules with myself as referee to add a few "fog of war"

touches. (Ships firing into their own side, confused by the

smoke; signalling muddle, etc.) It was one of the larger

battles we've fought this far -- although not the largest:

remind me to tell you about the Ceylon Campaign one of

these days, if I can ever get the shell-shocked scenario

designer to write in anything but crayon.

The following battle was fought using my HEART OF

OAK rules with myself as referee to add a few "fog of war"

touches. (Ships firing into their own side, confused by the

smoke; signalling muddle, etc.) It was one of the larger

battles we've fought this far -- although not the largest:

remind me to tell you about the Ceylon Campaign one of

these days, if I can ever get the shell-shocked scenario

designer to write in anything but crayon.

I had long been interested in the possibility of forcing a single naval commander to deal with a superb fleet, the British, allied to a lubberly collection of perpetual losers, the Spanish -- battling a mediocrity, the French, who would normally be beaten by the former and thrash the latter. The British and the Spanish were allied briefly against Revolutionary France in the early 1790's. As this was also the time of the Terror, I was allowed to set up a situation reflecting another intriguing concept: forcing each commander to deal with a subordinate whom he cannot trust.

Forces

The forces in our games had always cooperated remarkably well with their teammates, at least within the limits of signalling and ability: even in the Ceylon campaign, Suffren's subordinates followed his orders most of the time, in direct contrast to the meddlesome idiots plaguing the real Suffren. I decided to create a scenario that would sow distrust between the commanders. This proved to be surprisingly easy to do.

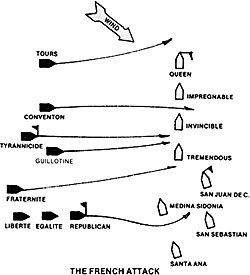

The Allied fleet consisted of four British and four Spanish vessels. The British forces were the 98-gun QUEEN (crack crew; smart sailer), and three 74-gun liners, IMPREGNABLE (average crew; smart sailor), INVINCIBLE (good crew; average sailor), and TREMENDOUS (crack crew; average sailer); allied to the Spanish 112-gun SAN JUAN DE CAPISTRANO (average crew; smart sailer), the 80-gun SANTA ANA (average crew; average sailer), and the 74s SAN SEBASTIAN (green crew; sluggish sailer) and MEDINA SIDONIA (green crew; smart sailer).

They were pitted against eight French ships: the 120gun TYRANNICIDE (good crew; sluggish sailer), the 11Q-gun REPUBLICAN (average crew; average sailer), the 80-gunners LA CONVENTION (green crew; average sailer) and TOURS (poor crew; sluggish sailer), plus the 74s LIBERTE (green crew; average sailer), EGALITE (crack crew, average sailer), FRATERNITE (good crew; sluggish sailer), and GUILLOTINE (crack crew; smart sailer).

The British admiral, Sir Chowdisley Fluggers, was played by Phil Hernandez, a veteran of numerous HEART OF OAK battles; the Spanish admiral was played by Joe Chacon, who had never played the game before. It was thus easy to set the two players to distrusting one another, simply on the grounds of experience: I also forced them to communicate one another entirely through signals, which prevented them from conferring on strategy. The fact that Phil chose to use tactics that Joe did not at all agree with helped considerably in obtaining the unique results of this battle.

Distrust

With the French, distrust was also remarkably easy to place. The senior French admiral was played by Vic Milan; the Junior admiral was William Chasko. Both are serious gamers with a large independent streak; they are also good friends who have never been known to trust one another any farther than each could throw a five-ton siege mortar.

In designing the scenario descriptions, I made it appear to each as if the other was fully prepared to betray him to the Terror; I refused to allow them to communicate with one another except through signalling, which considerably heightened distrust; and I also suggested to each that they alone could attack the Spanish and defeat them easily, leaving the other in the lurch, as it were, to deal with the competent British.

I also told each player that victory conditions would be determined entirely on their individual successes not team successes: the British could win independently of the Spanish; each French admiral could win while the other lost.

Placement

The French squadron was placed upwind of the Allies,

outside of maximum gunshot to allow both sides a chance

to maneuver. The French were thus given the weather

gage by the scenario, although, as the HEART OF OAK

rules point out, the weather gage is decidedly a mixed blessing.

The French squadron was placed upwind of the Allies,

outside of maximum gunshot to allow both sides a chance

to maneuver. The French were thus given the weather

gage by the scenario, although, as the HEART OF OAK

rules point out, the weather gage is decidedly a mixed blessing.

The British Admiral Fluggers decided to start the scenario with springs set on the anchor cables of all his ships. It was his opinion that the Spanish fleet, disorganized right at the start, would not be up to a battle of maneuver; he determined to fight from fixed positions, pivoting his ships as necessary to deliver their broadsides. Admiral Veldez, who had not been consulted, disagreed; he much preferred a battle of maneuver. It was this decision by Fluggers, more than any other, that determined the battle's outcome.

Crapaud's first order to his subordinate was TURN IN SUCCESSION, ATTACK/CLOSE ACTION, a remarkably aggressive command for a French naval leader. Petit-Teton was only too happy to oblige, but he determined to do some juggling of his formation FRATERNITE, in the lead, was a very slow ship, and Petit-Teton did not relish following the stately FRATERNITE into the hell of the enemy guns he much preferred attacking as fast as possible, and in a series of maneuvers Petit-Teton's flagship, the 110-gun threedecker REPUBLICAIN, was placed in the lead, followed by the EGALITE, LIBERTE, and, somewhat out of line, the slowest of the French ships, FRATERNITE.

Maneuvering

All this maneuvering was regarded by Admiral Crapaud as evidence of alarming incompetence: from his position, he could not see that Petit-Teton was forming a more efficient battle order he could only see French ships getting themselves in an unseemly tangle. After some futile signalling (VAN SQUADRON OUT OF PROPER FORMATION) and a few near-collisions among his own squadron, Crapaud lost patience entirely and signalled GENERAL CHASE. Crapaud's squadron turned in unison and bore down on the enemy.

The tactical situation was now rather unique: PetitTeton's lead squadron was bearing down on the enemy rear in line ahead, with FRATERNITE somewhat out of place and being rapidly passed by the faster French ships, while Crapaud's rear squadron was approaching the British in line abreast. This resulted in Crapaud's ships being more heavily damaged on the approach: each was fired on by its British opposite number, some taking a severe battering; but the only ship upon which the rear, Spanish squadron concentrated its mostly-ineffective fire was the lead ship, REPUBLICAIN, the only target the line-ahead formation offered.

Crapaud's initial battle plan had been foiled by the confusion between the two French commanders: he had anticipated both squadrons attacking in line ahead Petit- Teton passing through the Spanish squadron crushing it; with Crapaud passing between the Spaniards and the British, preventing the latter from interfering. Crapaud's plan might well have worked, the Spanish fleet being destroyed before the British could interfere, had Crapaud not lost patience and gone slambang into action. As it was, the British got their licks in on the approach.

REPUBLICAIN, little troubled by the fire of the Spanish on the approach, entered the Spanish "formation", executed a neat turn to larboard, and then its starboard broadside hurled 2400 pounds of iron shot into SANTA ANA's bows, a glorious bow-rake that staggered the Spaniard. REPUBLICAIN's second broadside was virtually as devastating as the first, and SANTA ANA's flag came fluttering down in surrender. Less than a minute after SANTA ANA's collapse, REPUBLICAIN crossed the stern of MEDINA SIDONIA, firing its fresh larboard broadside in such a staggering pointblank triple-shotted rake that the terrified green crew of the Spaniard hauled down their colors.

Double Victory

It was this amazing double-victory, in the opening moments of the French attack, that signalled to Admiral Veldez that Admiral Fluggers' strategy was not working. SAN JUAN and SAN SEBASTIAN swiftly cut their cables and made sail. REPUBLICAIN passed between them, and was handled severely, unable to efficiently work both broadsides after the initial rounds had been fired.

EGALITE was the next French ship to enter the Spanish fleet. She undoubtedly had the finest crew of any ship in Petit-Teton's squadron, but luck did not spare her this day. She was raked efficiently by the 112-gun SAN JUAN on approach; firing back, the plucky 74 was momentarily lost in the smoke and accidentally rammed SAN SEBASTIAN. She was raked mercilessly until she managed to cut free. LIBERTE, just behind, became confused in the smoke and fired into EGALITE by accident. Eventually EGALITE cut free from SAN SEBASTIAN and managed to stern-rake the Spaniard as the latter tried to escape. Surrounded by EGALITE, REPUBLICAIN, and LIBERTE, SAN SEBASTIAN was pummeled fiercely and finally surrendered.

SAN JUAN DE CAPISTRANO, Veldez' flagship, was the only Spanish ship to escape capture. Passing through the French formation, SAN JUAN managed to hit each French ship in its turn, eventually escaping to the eastward. Looking back on the smoke-enshrouded battle, Admiral Veldez congratulated himself on escaping the trap laid for him by the French and his own ally Fluggers, and decided not to re-enter the battle. He and his ship were next seen in Barcelona, complaining loudly of British perfidy.

All of Capaud's squadron were damaged on their approach to the British fleet, enough to worry the French admiral. He hoisted the signal ALL SHIPS ENGAGE ENEMY REAR SQUADRON, meaning that Petit-Teton was to aid him in attacking the British -- it was an order that Petit-Teton, who thought the signal meant he was to attack the Spanish, agreed with wholeheartedly. (Petit-Teton was rather more correct: at the opening of the scenario, and during most of the fight, the Allied ships were oriented so as to put the British in the lead.)

Accordingly Crapaud's weary pilgrims were given precious little aid, even though Petit-Teton had, for the most part, disposed of the Spanish squadron by the time Crapaud engaged. TOURS, on the end of the French line, passed outside of the British flagship QUEEN, receiving a series of crippling broadsides that eventually brought the Tricolor down in surrender. LA CONVENTION passed between IMPREGNABLE and INVINCIBLE and received even worse damage being struck repeatedly below the waterline, losing her mizzenmast and rudder, and eventually surrendering. LA CONVENTION was never captured by the British, but sank forty minutes after the conclusion of the battle.

The French flagship TYRANNICIDE bow-raked INVINCIBLE, doing serious damage. While TYRANNICIDE attempted to pass through the British line, INVINCIBLE spun on her cables, and the two ships came together, broadside to broadside. For a few minutes the ships battered each other, TYRANNICIDE receiving the worst of the blows, but eventually TYRANNICIDE broke free and the two ships drifted apart.

At the end of the British line, TREMENDOUS was in extreme difficulties. GUILLOTINE had approached to within ten yards of the British ship to deliver a bowrake of truly thunderous proportions. With their ears still ringing from the concussion, the crew of TREMENDOUS was staggered again -- FRATERNITE, the slowest of Petit- Teton's ships but one of the bestcrewed, had arrived at last, and delivered a stunning rake through TREMENDOUS's stern windows, resulting in a rate of 45% casualties in the British crew. GUILLOTINE drifted alongside the British bows and grappled. It looked as if the rakes would go on forever, and there was no help in sight: the Spanish had vanished, and the nearest British ship was fouled to TYRANNICIDE and unable to assist. The British surrendered, and GUILLOTINE's happy boarders took swift possession.

A British ship struck! TREMENDOUS was one of the

best-crewed ships in the fleet. Fluggers ordered his

survivors to cut their cables, and ran up the signal SAUVE

QUI PEUT ("Save himself who can.") Fortunately the British

captains were not French classists, and Fluggers later

reconsidered and got his remaining ships in order: QUEEN,

IMPREGNABLE, and INVINCIBLE swiftly formed line on the

starboard tack, heading west, ready to wear about and

enter the fight: QUEEN's prize crews had taken possession

of the French TOURS. SAN JUAN DE CAPISTRANO the

Spanish flagship, was still hanging about on the fringes of

the combat, and could be ordered into action, that is if

Veldez agreed.

A British ship struck! TREMENDOUS was one of the

best-crewed ships in the fleet. Fluggers ordered his

survivors to cut their cables, and ran up the signal SAUVE

QUI PEUT ("Save himself who can.") Fortunately the British

captains were not French classists, and Fluggers later

reconsidered and got his remaining ships in order: QUEEN,

IMPREGNABLE, and INVINCIBLE swiftly formed line on the

starboard tack, heading west, ready to wear about and

enter the fight: QUEEN's prize crews had taken possession

of the French TOURS. SAN JUAN DE CAPISTRANO the

Spanish flagship, was still hanging about on the fringes of

the combat, and could be ordered into action, that is if

Veldez agreed.

On the French side, all was not well. Three Spanish ships had been captured, along with a British twodecker, but TOURS had surrendered, LA CONVENTION was sinking, EGALITE was badly damaged, and all of the rest were damaged saving only FRATERNITE. The great moment of the battle had potentially arrived. The three surviving British ships were all in good shape, INVINCIBLE alone having taken serious damage. Would Fluggers, who now had the weather gage, turn his survivors about and engage the French in a do-or-die contest? Would Petit- Teton flushed with victory, adequately support Crapaud's remaining ships? Would Veldez, stung by defeat, assist his British ally? Would Crapaud be able to get his ships in order to resist a British attack?

Well, uh . . . the answer to the above questions is No. Vice-Admiral Fluggers decided that the captured TOURS and the sinking CONVENTION would more than adequately make up for the lost TREMENDOUS, particularly since his own flagship had taken TOURS -- no one would accuse him of cowardice and he could blame the loss of TREMENDOUS on a lack of Spanish cooperation. Fluggers and his prize blithely sailed off into the sunset, leaving the French commanders to argue over which one of them had won the battle.

The game pointed out some interesting concepts around which future games might be designed. It showed that to anchor a fleet against an enemy possessing the weather gage is an invitation to disaster. The enemy can pass through the line anywhere, at will, and is sure to gain deadly rakes. Historically, this is also pointed out by the outcomes of the battles of Aboukir Bay and Copenhagen. To anchor a fleet against an enemy beating upwind, however, as MacDonough did on Lake Champlain, might well be attended with greater success. Perhaps another scenario might be designed to test out this notion.

Related:

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. 1 #4

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1979 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com