Militia -- citizens enrolled and trained for home defense -- has played a prominent role in many modern wars. The militia tradition, as we in the West know it, antedates the formation of regular armies. England had its Saxon fyrd and, in Napoleonic times, its yeomanry. The

U.S. had its colonial militia and "minute companies," then state militias, and today, the National Guard. France had its feudal francs-archers and, during the Revolutionary-Napoleonic Wars, its Garde Nationale. These are formations with which we are familiar.

Militia -- citizens enrolled and trained for home defense -- has played a prominent role in many modern wars. The militia tradition, as we in the West know it, antedates the formation of regular armies. England had its Saxon fyrd and, in Napoleonic times, its yeomanry. The

U.S. had its colonial militia and "minute companies," then state militias, and today, the National Guard. France had its feudal francs-archers and, during the Revolutionary-Napoleonic Wars, its Garde Nationale. These are formations with which we are familiar.

Ranging farther afield, there is the Prussian landwehr of the Napoleonic era; what Prussian Napoleonic army would be complete without a landwehr contingent?

Then there is the opolchenie of Czarist Russia. opolchenie? Chances are you've never heard of them. But, nearly a quarter million strong, this Russian peasant militia helped turn back Napoleon's 1812 invasion of Mother Russia, and any Russian Napoleonic army worth its salt ought to include at least a few battalions of them. The object of this article is to help the Russophiles among you to do just that.

Beginnings

The beginnings of the Russian militia system may be traced to 16th century Muscovy. At that time the feudal Muscovite army was about 90% militia cavalry. These horsemen were the pomestnik dvoriani (gentry) and their men. The dvoriani cavalry were obligated to serve only for the duration of any campaign; when the threat to the state was ended, they went home.

With the passage of time the military pomestnik system grew inadequate to the needs of the Russian state. In the 17th century Muscovy was engaged in almost continual warfare. Also, new methods of warfare were being adopted in Russia, and the proportion of infantry in the army rose.

Many dvoriani loathe to serve as infantry or adopt firearms and drawn increasingly by domestic concerns, became netchikov (evaders). When Tsar Peter the Great attempted in 1695 the capture of the Turkish stronghold of Azov 22% of the dvoriani cavalry of Moscow called to arms evaded service in the campaign. Appalled, Peter liquidated the dvoriani cavalry (as he later did the Streltsi infantry, another undisciplined and privileged holdover from the medieval Muscovite army).

This was not the end of the Russian militia system, however. In 1700 Russia entered the long Great Northern War with Sweden (1700-21). Peasant militias -- in many cases bands of partisans -- were formed in many localities. W. Zweiguintzow, an expert on the Russian military, mentions one such formation, the "Landmilice" of the Ukraine, in his book, L'Armee russet.

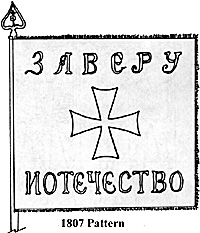

RUSSIAN MILITIA COLORS, 1807-12.

Militia Infantry Battalion Color, 1807 Pattern. Infantry battalions raised in the 1807 levee en masse received colors of the pattern shown with the "militia

cross" -- a Maltese Cross similar to crosses on Danish and Prussian landwehr colors -- and the motto, "For Faith and Country." The field of this color was raspberry red (Zweiguintzow says the shade was "more or less dark"), but some flags, not distributed to troops, had a white field.

The cross appeared in a variety of colors; Zweiguintzow cites white, yellow, sky blue, and green. The lettering was white. The color of the flagstaff was not recorded, the ornament at the tip of the flagstaff was iron.

Militia Infantry Battalion Color, 1807 Pattern. Infantry battalions raised in the 1807 levee en masse received colors of the pattern shown with the "militia

cross" -- a Maltese Cross similar to crosses on Danish and Prussian landwehr colors -- and the motto, "For Faith and Country." The field of this color was raspberry red (Zweiguintzow says the shade was "more or less dark"), but some flags, not distributed to troops, had a white field.

The cross appeared in a variety of colors; Zweiguintzow cites white, yellow, sky blue, and green. The lettering was white. The color of the flagstaff was not recorded, the ornament at the tip of the flagstaff was iron.

Banner of the Kaluga Militia, 1812. Many units carried Church banners instead of colors. This sketch shows a Church banner carried by the Kaluga infantry. The ground of the banner was sky blue; the ornamentation was white. The embroidered border and the cords and tassels were gold. The icons, which depict on one side the famous cathedral of Notre Dame de Kazan and on the other side St. Lawrence of Kaluga, were painted in natural colors.

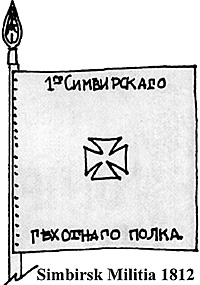

Color of the 1st Regiment, Simbirsk Militia, 1812. The field of this color was light green. The cross and inscriptions were gold. The flagstaff was black, and the ornament at its tip was gold.

Color of the 1st Regiment, Simbirsk Militia, 1812. The field of this color was light green. The cross and inscriptions were gold. The flagstaff was black, and the ornament at its tip was gold.

Uniforms

In 1713 these men were uniformed in gray coats and armed with surplus weapons. We know also from Zweiguintzow that no regulation uniforms were prescribed for the militia before 1736 and that they presented a "motley picture," being garbed in a mixture of peasant dress and military hand-me-downs.

Thereafter, the militia system continued, but not much is known of the militia organizations or their service record. The chief employment of the militia units seems to have been in defense of the frontiers of Russia against the Turks.

During the Napoleonic era the militia system remained unchanged until November 1806, when a decree ordering the enrollment and training of 612,000 serfs was published. This was the Russian equivalent of France's levee en masse.

It seems likely that this number was never realized because mainly the regular army was a constant drain on peasant manpower. Nevertheless, when Napoleon's GRANDE ARMEE crossed the Niemen in 1812 and embarked on its invasion of the Russian heartland, 223,361 men were raised in militia units to combat the invaders.

Only a fraction of these men actually saw service with the field armies. For example, in Kutuzov's army at the battle of Borodino there were 15,000 Moscow and Smolensk opolchenie in Tuchkov's lil Corps. This was 12.5 percent of the total strength of the Russian army. According to Christopher Duffy in his authoritative book BORODINO, the role of this militia was limited. Some were arrayed in masses behind the regular troops to deceive the French into thinking that the Russians had powerful uncommitted reserves; others assisted the wounded to dressing stations or patrolled rear areas for deserters.

It would be difficult to attempt to assess the combat effectiveness of the Russian opolchenie. Most units were poorly armed, ill-trained, and unexperienced. Roth von Schreckenstein. a German officer quoted by Duffy, described them as "raw Russian peasants clutching pikes and muskets which they scarcely knew how to wield."

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. 1 #3

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1979 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com