A number of tactical-level miniature rules (i.e., multiple stands per battalion) for eighteenth century warfare have appeared during the last several years, such as Thomas Åhrnfelt's Gå På (Acedia Press, 2002), Tod Kershner's Warfare in The Age of Reason (Emperor's Press Limited, 1998) and 18th Century Principles of War (T. M. Penn 2002.) The primary design focus of this latest generation has been on more the sequence of play and a sophisticated simulation of command control capabilities. The mechanics of play on a purely tactical level have remained relatively unchanged, however.

Once the attacking player has succeeded in positioning his battle line near the defending units, there is little to do but to advance, choose the most propitious moment to fire (as determined by the rules' fire resolution dynamics). Some rule sets allow opposing sides to close to contact; others force one side or the other to break before closing. In either case, both sides typically check morale at some point and the victorious side generally is that which inflicted the most casualties and was found to have the highest morale.

This sequence of game dynamics appears to mesh nicely with our current understanding of the eighteen century battlefield. After all, during the linear era of warfare, didn't opposing sides form line lengthy continuous lines? Once the army was in position, wasn't there few tactical options but to advance directly toward the enemy? For the colonel, even the brigadier general, there appears to have been little opportunity for initiative: the only meaningful tactical decision was when to order the men to fire.

A quick survey of available modern secondary military historical sources seems to support the notion that tactical level activity and decisions were of minor import during the final moments before opposing sides closed in an attempt to win the day with the arme blanche (i.e., cold steel.) This misconception has arisen in part because of the way military history has been studied. Until the twentieth century, most "military historians' were military officers and their primary concern was to investigate and explain past methods in order to better understand "modern" methods of fighting. The writings British Captain Nolan, the Belgian Jean Roemer, the French Captain Grivet, the American Col. Francis Lippitt, and the Prussian General Emanuel Warnery, for example, provide a tactically rich picture of how combat was conducted during this period. However, the academics who took over the task after the First World War tended to ignore the study of tactical level warfare, viewing it as largely irrelevant.

More recently, excellent historians such as David Chandler and Christopher Duffy, as well as numerous writers who started as "gamers" have undertaken to venture along the long road back to a more detailed and much more accurate accounting of military history. Nevertheless, a great amount of work in this area remains to be done. The problem is neither unwillingness, lack of dedication, or talent. The obstacle that has always stood in the way of a more detailed and accurate understanding of how warfare was fought during the flintlock era has always been the inaccessibility of the primary sources that would shed light on how warfare was actually conducted on the European battlefield, especially on the tactical level.

Fortunately, in the era of the Internet, microfilm technology and inexpensive long-distance travel, it is possible for the dedicated enthusiast to personally collect copies of invaluable, but highly obscure, geographically dispersed works that have long collected dust on the shelves of prestigious institutions.

As these period works are collected, dissected and analyzed here and there one finds some incredibly revealing descriptions of tactical practices and how they were employed in battle. In one source one finds a snippet of information about circa 1700 cavalry; another source yields information about their infantry counterparts. A third source might provide more information about the same army and arm, but only for a slightly later period, and so on. Slowly, one can assemble a detailed picture of the full array of tactics, just as one would piece together a giant jigsaw puzzle.

The resulting informational "diorama" not only yields a hitherto unknown richness of description and detail, that, of course, will incrementally add to our knowledge, but will also force a substantial revision to some of the basic assumptions we have about how war was fought in the early horse and musket period: the extent to which tactics were utilized during battle, their role in occasionally determining the outcome of an engagement, and the amount of variation from army to army and period to period. In fact, the picture that emerges will even force a revision in the definition of tactics, as well as the scope of elements (methods, practices, and doctrine) that are seen as making up each tactical system.

Tactical Variation between British and French Infantry, c 1703

The term "tactics", regardless of era, conjures up images of manouvers, formations, and fire delivery systems. The student of Napoleonic warfare has a relatively easy time cataloging the tactical components for each army in his chosen era. The military authorities in each major power published officially prescribed "drill booklets" (usually in the guise of "official regulations") that were in effect a lexicon of the manouvers, formations and methods of delivering fire that its infantry or cavalry were to employ on the parade ground and during battle. Someone interested in the tactical lexicon available to French infantry during the Napoleonic era, for example, can go directly to the Reglement concernant l'exercice et les maneouvres de l'infanterie sanctioned by the French Ministry of War on August 1, 1791.

[1]

The Rules and Regulations for the Formations, Field-exercise and Movements of his Majesties Forces published the British War Office serve as valuable a resource for those examining British infantry during this same period.

[2]

Although no such one-stop sources are available for Marlboroughian or even Fredrician-era armies, fortunately one can assemble just as comprehensive a description of tactical practices for each major army during the early eighteenth century by consulting a series of period military scientific treatises.

As these "drill booklets" are assembled for the various armies during the 1689-1763 period, it becomes evident that there was much more tactical variation between armies than has previously been recognized. In some cases, there was also a stream of subtle changes that occasionally had a significant impact on an army's overall tactical doctrine and practical methods for that arm.

Nowhere does his become more obvious than when one compares the tactics utilized by French infantry and cavalry during the Wars of the Spanish, Polish and Austrian Succession with those adopted by the British during the same period. Although both armies fought pre-dominantly in line, British and French infantry adopted a different version of this formation. British infantry typically fought in a 3-rank formation, except in those cases where the commander opted for a 6-rank line by "doubling the files." In contrast, French infantry fought in either five, four, and occasionally only three-rank lines. Again, French commanders occasionally increased the depth of a line to 10, 8, or 6 ranks by use of the doubling manuver.

[3]

There was also another difference between the French and British line which seeming small, would actually have a very significant impact there ability to manuver around and fight on the battleground. This was distance maintained between ranks and files. This changed as different tactical situation were encountered, and an more in-depth discussion of the doubling manouvers and changing distances between ranks and files has been reserved for the second installment of this article.

The lexicon of manouvers that the infantry in each of thee two armies also diverged at points. True, there were a number of drills and manouvers that were extremely similar if not identical, such as wheeling (quart de conversion), opening and closing of ranks and files, etc. On a conceptual level, the methods used to form line from the marching formation (what later would be called a "column") as well as the reverse process were similar. There were also notable differences, however. On a practical level, officers overseeing a French battalion going in and out of line had to count the steps taken by one tactical unit of the battalion before the next begin to execute its portion of the manuver, a very difficult and time consuming process. [5]

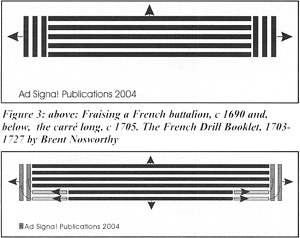

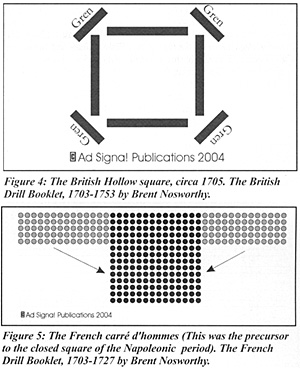

However, probably the greatest tactical difference was the formations to be used when forced to suddenly respond to enemy cavalry. During the heyday of so-called "linear warfare" infantry battalions along a lengthy line would try to maintain their current formation, even when they faced enemy horse. French infantry had developed several methods of bolstering the defensive capabilities of the battalion in line. During the mid-sixteenth century when the number of pikemen per battalion had generally been reduced to about a fifth of the battalion, two files of pikemen were re-positioned near either end of the battalion to protect its vulnerable flanks. This practice was known as "fraising the battalion".

[6]

British infantry, when the severity of the threat warranted a change of formation, tended to adopt a form of Hollow Square first popularized by the Dutch. The mestre de camp (what later would become a "colonel") of a French infantry regiment certainly had many more options. In addition to the carré vuide (essentially, the same hollow square used by the British), some French regimental commanders occasionally resorted to the carré d'hommes, a prototypical variant of the carré plein, or closed square, that would later be associated with the later Napoleonic period.

The following subsection is excerpted from the author's book, The Bloody Crucible of Courage (Carroll and Graf, 2003.)

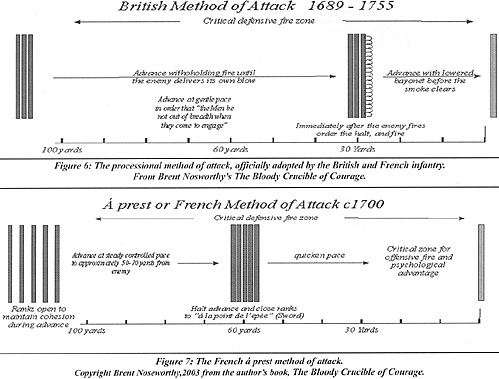

There is an all-too-common tendency to limit the discussion of an army's tactics to the assortment of formations that were used, how battalions and cavalry squadrons manuvered from one formation to another, and how they delivered fire. There was another extremely important dimension that has been frequently ignored or at least minimized. This was the doctrine and practices used to attack an adversary, or conversely to defend oneself when forced to adopt a more passive role.

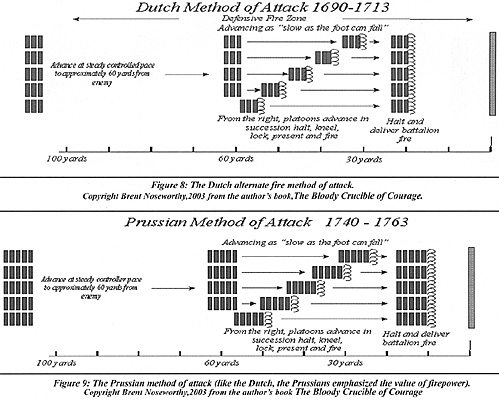

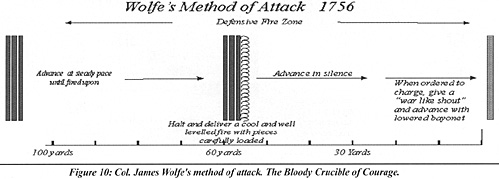

During the eighteenth century these methods of attack could be divided into two main schools of thought: one emphasized the importance of firepower; the other upheld the determined advance and the final rush with lowered bayonets. This issue was hotly debated throughout the period and number of different methods of attack and defense evolved. Overall, the Dutch and Prussians tended to favor the pro-firepower school, while the French choose the aggressive assault. By Napoleonic times, the British had crated a system that combined elements from both systems.

According to the à prest doctrine employed by many French commanders after 1690, infantry were to advance in an orderly fashion and with a deliberate gait until 50 to 70 paces from the enemy. [9] Prior to 1750s, French infantry did not employ cadenced marching and initially the ranks were often left about 13 feet apart. This meant that when the advancing line were about 50 paces from the enemy, the advance temporarily stopped and the ranks quickly closed to one or two feet apart. As soon as all was ready, the march resumed. However, the pace was speeded up and the men advanced à prest, that is, with a quickened step.

Following the established doctrine, French officers would prohibit their men from beginning to fire until they ordered them to do so during the final moments of the assault. See figure 7. [10]

According to Marshal Nicolas Catinat, who commanded the French Army of Italy during the 1690's, this tactic provided the attacker with a psychological advantage during the final moments of the attack. If the defenders fired at the attacker at any time during the last 100 paces of the approach, they were incapable of fire during the final seconds, precisely the time when a psychological edge was extremely critical. The realization that they could no longer fire and that the approaching enemy still could would demoralize the defenders as they fought their fears and did their best to stand their ground. The attackers, on the other hand, having not yet delivered their fire became all the more confidant, realizing they had the ability to fire on a now defenseless enemy. [11]

The counter to this tactic was for the defender to withhold its fire until the very last second. The defender not denuded of his fire would never become as demoralized as hoped. The threat of this counter measure lead most officers favoring the à prest assault to believe that the attacking force should withhold its fire until about 20 to 30 paces from the enemy, stop and deliver fire, and then run into the enemy before the latter could recover from the blow and return the fire. If this was executed properly, the defenders would be incapacitated and thrown into temporary confusion by this murderous volley, fired at extremely close range, and most likely would be unable to fire in the few seconds the attackers needed to cross the last 20 to 30 paces. Faced with an on rushing foe, the clouds of smoke from the whole offensive formation firing at once and the necessarily heavy casualties, the defenders almost certainly would break before contact was made.

Probably the best rationale for this offensive tactic was provided by the Marquis de Santa-Cruz, a Spanish military authority and tactician. Santa-Cruz believed that when an attacking force neared an enemy that made use of well-timed volleys, the attacker was at a distinct disadvantage if he simply attempted to ignore the fire and rush in and settle the matter with the lowered bayonet. Faced with the terrible buzzing and whistling of the musket balls and the unsettling sight of the dead and wounded, the attackers would become increasingly consternated. Less experienced men were particularly affected by the ordeal. Many now extremely agitated would begin to fire despite their officers' wishes. Trembling and exhibiting much diminished muscular control, these shots, totally unaimed, ended up being directed "as much at the sky as the earth."

To counteract this possibility, sometime in the late 1600's, the Dutch devised a method of assault in which the attacking force periodically stopped and a portion of the formation delivered a volley, before stepping off once again. The attacking formation would march with shouldered arms until it had approached close enough to inflict meaningful casualties upon the defenders. Captain Humphrey Bland estimated this distance to be around 60 paces. While marching, the men in the battalion advanced with "recovered arms," which in this case meant the musket was held pointing straight up a few inches in front of the soldier. A few moments later, the right-most platoon in the battalion would quickly advance until its rear rank was even with the front rank elsewhere along the front. At this point, its men would halt, kneel, lock, present and fire. The battalion meanwhile continued to advance "as slow as the foot can fall" so the battalion's cohesion was not lost. This slow and deliberate gait also allowed the men who fired to reload while they continued to advance.

After the right-most platoon fired, the one on the left flank would spring forward and fire. Then it became the turn of the second platoon from the right, followed by that of the second platoon on the left. This process of alternating fire between platoons on the right and left of the battalion continued until all platoons had fired. As soon as all the platoons had reloaded, the battalion would switch from the slow, deliberate method of marching to a more normal pace. At some point, the platoons in the battalion would recommence the "alternate fire" just described, so that it was expected that the defenders would be subjected to two or three complete fires by the time the attackers were 20 paces or so distant. At this point, the entire battalion would fire before rushing in with lowered bayonets. Bland informs us that this method often caused the defenders to break after a single round of firing, and even when the attackers had to advance to close range usually there were few casualties inflicted on the advancing forces. See figure 9. [13]

Despite it virtues, this Dutch method of firing while advancing was difficult to perform and demanded the highest level of discipline. A Prussian variant evolved during the mid-1700s. Frederick the Great's father, Frederick William I, held these Dutch methods in great esteem, and the epitome of the martinet, he compelled his infantry to spend countless hours unerringly repeating the newly introduced cadenced manual of arms. In this cadenced version, every man along the firing line performed the same step at the same instant. The expectation was that the men now firing much more quickly would crush the opposition by sheer weight of fire. Although there is little evidence that this tactic ever caused the expected casualties, its psychological impact became apparent during Mollwitz (1741), the Prussian infantry's first battle under the young Frederick the Great. The cadenced manual of arms and this "quick fire" system quickly became de rigueur throughout most of Europe and Allied tactics could be found advocating this method of attack as late as 1811.

[14]

Ironically, just as the Prussian cadenced manual of arms and "quick fire" system were gaining in popularity, there was a British lieutenant colonel who was honing his own tactical system. Though only adopted on a widespread basis more than fifty years after his death, this new tactical doctrine nevertheless had a monumental impact upon how the British infantryman would conduct himself against the French in the Iberian Peninsula and at Waterloo. In 1755, Lt.-Col. James Wolfe wrote a set of instructions for his Twentieth Regiment of Foot. Unlike many of his peers who had a decided preference for either the exclusive reliance upon the bayonet or the musket during the attack, Wolfe advocated a compromise where the two weapons worked synergistically together to produce a total impact greater than either component.

Later generations would attribute the continuous string of British victories over the French between the 1808-1815 to the greater firepower capabilities of the British line and the more accurate fire of the British infantrymen making up this formation. This largely ignores the sea of available memoirs and official reports and appears to be a rather self-serving effort to re-interpret historical events in terms of newly acquired sensibilities among late nineteenth century historians that arose from rapid firing weapons and new conceptions, such as a rate of fire, firepower, etc. More recent studies suggest that a quick but deadly close range fire followed by a determined bayonet charge, where the soldier's emotions where effectively held in check to the final moment, was the real reason for British victory. [16]

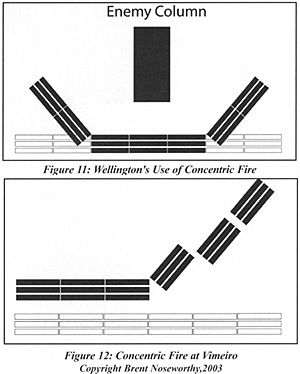

There has been yet one other tactical dimension that has been mostly ignored; this is what might be called "reactive or situational tactics." As the name implies, these tactics were employed in neatly defined situations, usually as a response to a specific type of enemy threat.

We tend to think that skirmishers were introduced during French revolutionary times, but prototypical skirmishing tactics were common throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The British use of "small parties" serves as an excellent example not only of prototypical skirmishing during the Marlboroughian era but also of reactive tactics. The practice of sending in several waves of cavalry squadrons became increasingly popular during the War of Spanish Succession. It wasn't always feasible to form Hollow Square. In his Treatise on Military Discipline Bland describes how in this case officers were advised to detach four or five groups, each made up of 4-5 files from the third firing along various parts of the battalion line. To prevent the cavalry from prematurely discovering the defender's designs, these small parties were to wait until the cavalry were in "full march" and then advance 10 - 12 paces immediately in front. There, they were to wait until the enemy horse had closed to within 30 - 40 paces, deliver fire and quickly return to their places in the line. The purpose of these "small parties" was to frustrate the first or even the second wave of cavalry which were usually intended only as feints, so that the main body of the battalion reserved its fire for the third wave of cavalry that could be relied upon to try to charge home in earnest. [17] One finds similar tactics employed throughout this period by almost every army, including the cavalry arm. [18]

British infantry occasionally did employ such tactics during the battle of Vimeiro (Aug. 21, 1808) when the right wing of Colonel Walker's 50th Foot advanced in echelon and overpowered Thomières' Brigade with a concentric fire. see figure 12. [20]

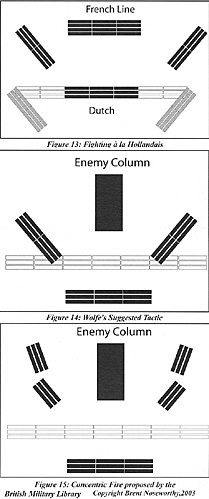

Actually the tactic of swinging in part of a line to partially envelop a narrower enemy formation certainly was anything but new and can be traced back to the early eighteenth century. A clue about the ultimate origin is to be found in a relatively rare, polemical work, Sentimens d'un homme de guerre sur le nouveau systême du chevalier de Folard, written in the early 1730s to refute the theories of the Chevalier de Folard, then gaining a following among the French military. In one of his arguments, the author boasts that were he to be attacked by one of Folard's monstrous columns, he would "bend" six platoons on either side to fight à la Hollandais. A diagram in this work shows that these angled attacks were formed by first wheeling backwards and inward by 50 paces, and then, if necessary, advancing these forward to threatened the flanks of the hostile column. [21]

There is some evidence some French officers occasionally copied the practice. In his Art de la guerre, Marshal the Marquis de Puységur instructed his regimental commanders when facing a narrower enemy battalion to wheel the two flank companies on either side of the battalion about 45 degrees forward and then order a "converging fire".

[22]

This practice was not completely unknown in Britain where one officer displaying great promise instructed his regiment, to employ these tactics when the occasion arose. A portion of the orders issued by then Lieutenant Colonel James Wolfe on Dec. 15, 1755 to the 20th Foot contained the following injunctions:

If the center of the battalion is attacked by a column, the wings must be extremely careful to fire obliquely. That part of the battalion against which the column marches, must reserve their fire, and if they have time to put two or three bullets in their pieces, it must be done. When the column is within twenty yards they must fire with a good aim, which will necessarily stop them a little. This body may then open from the center, and retire by files towards the wings of the regiment, while the neighboring platoons wheel to the right and left, and either fire, if they are loaded, or close up and charge with their bayonets. [23]

Although issued to a single regiment, these instructions would have a profound impact on British practices. Along with other orders and instructions these were published posthumously in 1768, as General Wolfe's Instructions to Young Officers. Going through several editions, this work along with De Saxe's Mes Reveries was the most popular of military scientific writings among British officers up to and during the Napoleonic Wars. See figure 14.

During the late 1790s a periodical entitled The British Military Library was published. Its stated purpose was to reprint rare and foreign military scientific works and to provide a forum for analysis and debate among British officers. Within its pages a series of articles appeared on how British infantry was to attack and defend in rough, hilly terrain; just the type of ground, incidentally, British forces would later fight over in Spain and Portugal.

In an article entitled "On the Defence of Heights By Light Infantry" that appeared in June 1799, its author advised defenders if attacked by one or more narrow columns to "make a slow retrograde movement, keeping up a brisk fire, while those on the right and left fall on the flanks of the enemy's column, and endeavor to throw it into confusion."

[24]

What is this but the "converging half-moon" described by Oman, albeit formed by retiring the battalion's center instead of advancing the wings? See figure 15.

The above discussion is but an introductory assay into the complex and surprising variegated universe of tactics during the flintlock era. A truly comprehensive treatment would necessarily be many times more than what could be covered in a series of articles. Nevertheless, it becomes clear even from this limited analysis that there were a wealth of tactics and tactical systems, many of which never had been isolated and identified by historians. It is equally clear that there were differences between the tactics employed by one army versus those used by another, and occasionally these differences resulted in substantial differences in performance and capabilities.

Any set of tactical rules that seeks to set a new standard of realism, therefore, must not only include these various tactics but devise a way to realistically differentiate the cavalry and infantry in each army from its contemporaries.

The onus in this endeavor does not completely fall of the shoulders of the rules writer/simulation designer alone, however. Historians, as well as enthusiasts who also apply themselves to this task, must eventually assemble what can be characterized as an encyclopedia of tactics during the flintlock era (1689-1853.)

Part Two of this article will explore the possible effect of this new wealth of tactical-level information might have on future tactical level miniature rules sets.

[1] France - Ministre De La Guerre; Reglement concernant l'exercice et les maneouvres de l'infanterie (August 1 1791), Paris, 1821.

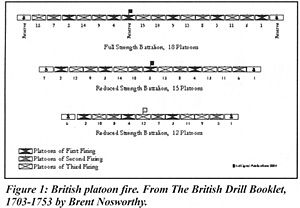

There was an even greater difference between the fire systems employed by British and French infantry. French infantry tended to continue to rely on a fire by ranks system that required the men along front-most rank to return to the rear of the formation after firing in order to reload. This was an old traditional method that had been perfected by the Dutch during the 1660s and 70s. Younger officers in the British infantry, on the other hand, favored various versions of the newly introduced platoon fire. Their older, veteran counterparts generally were content to continue using the fire by ranks system that had served them well during the Nine Years' War (1688-1697). In this system, each system fired one after the other, usually starting with the rear rank and proceeding to the front. See figure 1. [4]

There was an even greater difference between the fire systems employed by British and French infantry. French infantry tended to continue to rely on a fire by ranks system that required the men along front-most rank to return to the rear of the formation after firing in order to reload. This was an old traditional method that had been perfected by the Dutch during the 1660s and 70s. Younger officers in the British infantry, on the other hand, favored various versions of the newly introduced platoon fire. Their older, veteran counterparts generally were content to continue using the fire by ranks system that had served them well during the Nine Years' War (1688-1697). In this system, each system fired one after the other, usually starting with the rear rank and proceeding to the front. See figure 1. [4]

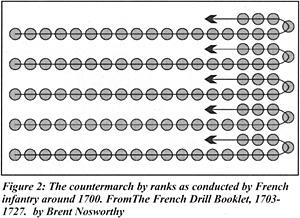

Another difference between French and British manouvers was how battalion commanders in each army tended to effect minor positional changes and adjustments. The British with their thinner, but more densely packed lines tended to rely on the wheel to face to the rear or move a battalion enough to give others units to pass through from the rear. To achieve the same results, the French frequently relied on countermarches, a type of manuver most British officers felt was too cumbersome and complicated to be practically executed in proximity to the enemy. See Figure 2.

Another difference between French and British manouvers was how battalion commanders in each army tended to effect minor positional changes and adjustments. The British with their thinner, but more densely packed lines tended to rely on the wheel to face to the rear or move a battalion enough to give others units to pass through from the rear. To achieve the same results, the French frequently relied on countermarches, a type of manuver most British officers felt was too cumbersome and complicated to be practically executed in proximity to the enemy. See Figure 2.

The concepts underlying this defensive posture survived the pike. The French infantry regulations of March 2 1703 allowed the formation of the carré long (Long Square.) The six men on either end of the last two ranks wheeled so that they now were formed along the flank of the battalion and facing outward. The remaining men along these two ranks spread out to fill up the space of the 12 men who left the ranks and then faced to the rear. All sides (front, read and sides) were then ordered to close ranks to the point of the sword, i.e., to 2 grand paces, and then, if the enemy was near, deliver a general discharge of their firelocks. See figure 3. [7]

The concepts underlying this defensive posture survived the pike. The French infantry regulations of March 2 1703 allowed the formation of the carré long (Long Square.) The six men on either end of the last two ranks wheeled so that they now were formed along the flank of the battalion and facing outward. The remaining men along these two ranks spread out to fill up the space of the 12 men who left the ranks and then faced to the rear. All sides (front, read and sides) were then ordered to close ranks to the point of the sword, i.e., to 2 grand paces, and then, if the enemy was near, deliver a general discharge of their firelocks. See figure 3. [7]

In theory, French infantry could also employ other massive anti-cavalry formations, such as the croix en travers, croix de Lorraine, and the croix de Lorraine double, which were still officially "on the books." However, by the start of the War of Spanish Succession these were considered far too clumsy and no officer ever seriously considered using these obsolete formations under fire.

[8]

In theory, French infantry could also employ other massive anti-cavalry formations, such as the croix en travers, croix de Lorraine, and the croix de Lorraine double, which were still officially "on the books." However, by the start of the War of Spanish Succession these were considered far too clumsy and no officer ever seriously considered using these obsolete formations under fire.

[8]

Methods of Attack and Defense

This type of doctrine, which could be called "methods of attack and defense," determined the role of firepower during the attack or defense, the moment it was to used, as well as how that fire was to be orchestrated. If also prescribed if and when a bayonet charge was to be executed. See figure 6.

This type of doctrine, which could be called "methods of attack and defense," determined the role of firepower during the attack or defense, the moment it was to used, as well as how that fire was to be orchestrated. If also prescribed if and when a bayonet charge was to be executed. See figure 6.

The result was that when and if the attackers made it to 20 or 30 paces from the defenders, their numbers were diminished through casualties and desertion and whatever forces did remain were no longer in order. The defenders who remained relatively composed could easily send the attackers reeling back if at the right moment they counterattacked with lowered bayonets. See figure 8. [12]

The result was that when and if the attackers made it to 20 or 30 paces from the defenders, their numbers were diminished through casualties and desertion and whatever forces did remain were no longer in order. The defenders who remained relatively composed could easily send the attackers reeling back if at the right moment they counterattacked with lowered bayonets. See figure 8. [12]

Wolfe recognized that as much as the officers urged their men to fire repeatedly, once the two sides had advanced sufficiently close, one side or the other would quickly break into a bayonet charge. Specifically, rejecting the Prussian quick fire system then coming into vogue, Wolfe enjoined his men to deliver "a cool and well leveled fire, with the pieces carefully loaded," arguing that this was "much more destructive and formidable than the quickest fire in confusion." The manner in which his regiment was to conduct the bayonet charge was self-consciously different from how it was normally conducted by other British regiments in those days. Instead of yelling or crying out, they were to remain completely silent, even if every other regiment along the line was yelling at the top of their lungs. Only when ordered to charge were they to give a "war-like shout" and then immediately rush in with lowered bayonet. [15]

Wolfe recognized that as much as the officers urged their men to fire repeatedly, once the two sides had advanced sufficiently close, one side or the other would quickly break into a bayonet charge. Specifically, rejecting the Prussian quick fire system then coming into vogue, Wolfe enjoined his men to deliver "a cool and well leveled fire, with the pieces carefully loaded," arguing that this was "much more destructive and formidable than the quickest fire in confusion." The manner in which his regiment was to conduct the bayonet charge was self-consciously different from how it was normally conducted by other British regiments in those days. Instead of yelling or crying out, they were to remain completely silent, even if every other regiment along the line was yelling at the top of their lungs. Only when ordered to charge were they to give a "war-like shout" and then immediately rush in with lowered bayonet. [15]

Reactive or Situational Tactics

Readers, however, are probably more familiar with another reactive tactic that is closely associated with British infantry during the Peninsular (War 1807-1814.) In his highly influential writings, Sir Charles Oman has attributed a significant part of Wellington's success the tactics his troops used to repel French columns of attack. Hidden behind a small hill or undulation, the British defenders would wait until the enemy had approached to within medium or close range and then unleash a destructive fire. If possible, the British battalion directly in front of the oncoming French column would swing its wings forward "in a Shallow Crescent." After firing, they would rush in with lowered bayonet. See figure 11. [19]

Readers, however, are probably more familiar with another reactive tactic that is closely associated with British infantry during the Peninsular (War 1807-1814.) In his highly influential writings, Sir Charles Oman has attributed a significant part of Wellington's success the tactics his troops used to repel French columns of attack. Hidden behind a small hill or undulation, the British defenders would wait until the enemy had approached to within medium or close range and then unleash a destructive fire. If possible, the British battalion directly in front of the oncoming French column would swing its wings forward "in a Shallow Crescent." After firing, they would rush in with lowered bayonet. See figure 11. [19]

The Dutch had adopted the long thin, continuous lines long before the French. The latter had frequently attacked with large intervals between battalions and it is natural, therefore, that the Dutch quickly developed an effective method to attack the vulnerable exposed flanks of the French battalions. See figure 13.

The Dutch had adopted the long thin, continuous lines long before the French. The latter had frequently attacked with large intervals between battalions and it is natural, therefore, that the Dutch quickly developed an effective method to attack the vulnerable exposed flanks of the French battalions. See figure 13.

NOTES

[2] Great Britain, The War Office; Rules and Regulations for the Formations, Field-exercise and Movements of his Majesties Forces, London, 1798.

[3] Boone, Nicholas; Military Discipline: The Compleat Soldier; Second Edition, Boston, 1706, pp. 30-32, 40-44; Bland, Humphrey, Treatise of Military Discipline, London, 1727, pp. 10; 7, 48-49; Mallet, Allain Manesson; Les travaux de mars, 1696 edition, p. 57.

[4] Bland, pp. 81-82. Le Blond, Guillaume; Élemens de Tactique; Paris, 1758, p. 406. also see Nosworthy, Brent, The Anatomy of Victory, Chapter 3, infantry fire systems,pp.47-63 for a description of period methods of delivering fire.

[5] Puységur, Jacques Françoise de Chastenhat (maréchal de France; Marquis de); Art de la guerre par principes et par règles; 2 vols., Paris, Quarto version, 1748, Octo version, 1749, Vol. 1, p. 72.

[6] Puysequr, Vol I, Quarto, p. 70; Octo, p. 143, also Bellehomme,Victor L; Histoire de l'infanterie en France, 5 volumes, Paris, 1893-1902, Vol. 2, p. 320

[7] Lt.-Col. de Guignard, Ècole de mars, 2 volumes, Paris, 1725, Vol. I, p. 674.

[8] Ècole de Mars, Vol. I, pp. 635-636.

[9] Quincy, op. cit., Vol. VII, p. 60.

[10] Colin, p. 25.

[11] Cited in Colin, p. 25.

[12] Cited in Le Blond, pp. 416-417.

[13] Bland, First Ed.; pp. 145-147.

[14] Müller, William, Vol. II, p. 186.

[15] Wolfe, pp. 47, 49, 52.

[16] Nosworthy, Sir Charles Oman; , London, 1999, pp. 231-263.

[17] Bland, 1st edition, pp. 92-94. A more detailed description of this tactic can be found in Brent Nosworthy's The British Drill Booklet, circa 1703-1753, Saint John's, Newfoundland, 2004

[18] Bland, pp. 92-93; "Miscellaneous Observations, Anecdotes, etc." in The British Military Library, Vol. I; p. 119; de Saxe, Maurice ; Reveries on the Art of War; Harrisburg, Pa., 1944, pp. 47-48; Wolf; James; General Wolfe's Instructions to Young Officers; (2nd Edition), London, 1780, pp. 50-51.

[19] Charles Oman; Wellington's Army, p. 89; Studies of the Napoleonic Wars, pp. 105-106.

[20] Col. Flyer, History of the 50th (or the Queen's) Regiment, London, 1851, p. 151; cited in Paddy Griffith's Forward into Battle, p. 20.

[21] Anonymous, but generally attributed to Savorin; Sentimens d'un homme de guerre sur le nouveau systême du chevalier de Folard, Paris, 1733, p. 100, & Plate IV opposite p. 103.

[22] Puységur, Quarto version, Vol. I, p. 153.

[23] Wolfe, James; General Wolfe's Instructions to Young Officers, Second edition, 1780, p. 52.

[24] On the Attack and Defence of Unfortified Heights, British Military Library, Vol. I, No. 9 (June 1799), p. 346.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier # 91

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com