When Rob Hamper (The Courier Napoleonic Editor - ED) suggested that I might like to write a piece for The Courier, we agreed that it would contain not only the areas that interested me most in Napoleonic gaming but also some practical suggestions as to how these might be incorporated into readers game play.

When Rob Hamper (The Courier Napoleonic Editor - ED) suggested that I might like to write a piece for The Courier, we agreed that it would contain not only the areas that interested me most in Napoleonic gaming but also some practical suggestions as to how these might be incorporated into readers game play.

British squares at Waterloo were well aware of their “Situation”.

As a result I now offer a practical device or two that I think might interest those of you who wish to represent the Command and Control aspects of Napoleonic Battles as viewed in the light of Situational Awareness.

I have deliberately tried to keep this part a simple affair, for two reasons. Firstly, so that any ideas people may wish to use can be readily implanted into whatever rules they currently play. Secondly, that such is the nature of the subject, it would be a very easy matter to end up writing enough material for an entire set of rules and thereby defeat the object of the original brief.

I would also like to note that these suggestions are only suggestions, based on my view of the period. I’m more than aware that they could be seen as either making things complicated, or not giving sufficient account to the many additional areas of Clausewitzian friction, beloved by some authors, depending on your viewpoint.

Situational Awareness - A Reprise

You may recall that in the first part of my article [See THE COURIER #88 - Ed.] I used Mica Endsley’s definitions of SA in terms of a model for how Command works:

Perception: acquiring the available facts

Comprehension: understanding the facts in relation to our own knowledge of such situations

Projection: envisioning how the situation is likely to develop in the future, provided it is not acted upon by an outside force

Prediction: evaluating how outside forces may act upon the situation to affect our projections

These steps led to the Decision and therefore the Order issuing process. This can also be described by the OODA loop (Observation, Orientation, Decision, Action) or Boyd Cycle, as it otherwise known. Alternatively, for those who prefer it in US Army parlance, Sees – Understands – Decides – Implements – Executes. Some, or all, of this can be modelled in various ways, with varying levels of complexity. However, in hobby wargames terms, the first two of Endsley’s quartet are really all we can encompass via rules. The rest must be generated in the players’ heads. Actually, it might also be argued that Comprehension could easily be reduced to a coin toss, in that ultimately all that matters is if a General really did understand what he saw/had been told about, or he did not.

However, it is the acquisition of the information that the “coin toss” is based on that should really concern us. Most experienced gamers would agree that players have access to unreal levels of information. Particularly when it comes to troop deployment and movements. So restrictions on actions and decisions based on limiting information are the key to a more realistic game. Please note I say “more realistic”, never imagine that the term “realistic” as a definitive where wargames are concerned.

Possible Means to The End

OK, how do we go about an improvement? Well, firstly, just to remind you of my preconditions. These suggestions will be simple and have cross platform utility. There will be places where you will have to fill in the blanks in terms of the rules you use, as you will know them better than I do but here goes!

Practical Woodwork 1

Firstly dear friends, let me introduce that physical device I spoke of - THE COMMERFORD CONE!

Say what? Never heard of it! Well maybe not, but lots of you will have used something very like it. Remember Canister Templates? Those little card or acetate triangular ‘do dads’ where you used to put the pointy end against your artillery base and every figure covered by its area was deemed hit. Look out! It’s about to make a comeback in the name of the first element of SA – Perception.

The 21st century version of this old friend is not to determine casualties, although it might cause a few later in the game. Rather its purpose is to provide a direct physical link to your command figures and whatever visibility conditions are determined by your rule set. For those of you shameful enough not to have visibility conditions it also provides an excuse (if any were needed) to invent some.

As an example let me at once turn to Napoleonic Principals of War, which you may recall I spoke of last time. In these rules observation is tied to command figures that are allowed to observe from their current location at a particular point in the game turn. This is of course subject to line of sight and successful dice throw against an observation chart, I might add that those I would consider “proper” charts note both the positions of the observer and the observed when making this assessment.

My point in introducing the cone was to codify and restrict this process in a way that is clear to both sides on what could, or could not, be counted in the visible area from the point of observation. My intention is that perception of our little 15/25mm counter part be contained within a representative area that would have some relation to the restricted view provided on a battlefield. Both in terms of the limits of human observational powers and the smoke and terrain undulations that table tops are very bad at emulating.

The cone can be made from pretty much, anything. It so happens I chose ¼ inch dowel and 2mm thick ply for mine but that’s up to you if you wish to make one for yourself. The Base angle is set at 60 degrees, which I felt gave a reasonable figure for an area of concentrated vision. Normal adult peripheral vision ranges from 170 to 150 degrees dependent on age but the idea here is to represent a studied view through obscuration achieved under testing circumstances. As such, a concentrated view will have a much narrower angle. Please note that although I have no particular adherence to Isosceles you can feel free to set your triangulation to any degree you feel fit.

You will note that I have deliberately not made the contact area part of the triangle. This is to ensure that players hold the device in base to base contact with the command figure, or are required to hold the tail of the piece directly over the figure base. This will avoid the subtle waving to left or right that might ensue in the hope of an increased field of view. You can make the overall length equal to the greatest visual distance permitted, if your rule set has observation. Or you can measure off a scale distance of approximately 1200 meters, which corresponds with US Army observation trials, as an optimum for visual acquisition of a target, under battlefield conditions in average Northern European terrain.

Using the device you can then determine a possible viewing area for you miniature self. Anything inside the cone is a possibility for a sighting, subject to whatever constraints exist in your rules or those you might wish to add. The overall objective is to cut down on player’s ability to claim knowledge acquired not just through what might be deemed possible to see but on the degree of opportunity to observe. It brings observation to table level and away from the players’ personal height above the playing surface and puts definition into the general woolly agreement on what can be seen.

You may wish to set a limit on the number of observations per turn or have a rule where either movement of a commander, or observation can be carried out in the same period but not both. Rules that generate action points per turn for commanders can assist in that regard by forcing a choice between a number of possible actions only one of which is observation.

The whole idea is to restrict player’s Situational Awareness and make them active in attempting to increase it in a manner that reflects real commanders problems. It is, if you like, the enforcement of the real dilemma of standing back to observe the action and having more idea of what’s going on. Or, getting down in the dirt and trying to make things happen by direct intervention while losing the plot.

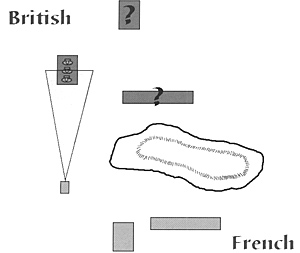

Commerford Cone

Commerford Cone

The ‘Commerford Cone’ consists of three dowels glued together and to a thin piece of card or ply. The angle of the triangle sets the degree of observation, which should be fixed as the players see fit. David suggests 60 degrees to simulate concentrated observation. The ply, although stepped, is all one piece. The width of the bottom should correspond with the width of a command figure base so as to centralize the view.

The length of the cone should correlate to maximum practical visual range as set by the rules in use. The cone can even be marked with distances that represent limited visibility i.e. dawn, fog, snow or smoke.

Naturally, there are other ways to construct the cone. The important thing is to be able to limit the information the command figure can access to that which might be realistically available.

Practical Woodwork 2

This is an adjunct to the observation cone and is representative of interference with the remaining elements of SA, those which effect the understanding of what is perceived and what you do about it.

Now here again we are dealing at a simplified level but the basic idea is to show that just because you have seen something you will not necessarily know what it is nor what its intentions are. To this end we need to block more information. Wooden block to be exact!

Now plenty of you will already use numbered wood blocks or something similar to represent units hidden movement. My suggestion is that you take that a bit further by never representing units on the table (even in the second or subsequent line of battle) by actual figures, unless a commander on a higher elevation can observe them.

Furthermore, when units move out of observation, due to terrain or other reasons (retiring or routing behind the front line for example) that you replace them with three, yes three, blocks. When they move off again the player then moves all three but of course only one will be the actual unit. This decreases your opponent’s chance of understanding/perceiving your intentions particularly if they take diverse routes.

Now of course this means a good number of blocks and a bit of paper work. The latter is not just a matter of evidence for umpires of other players, after a number of units have moved in and out of terrain features you will need it too, just to keep track for yourself when re-designating ID numbers each time observed units are “re-blocked”!

However, I think its worth it, just to get round that rather unsatisfactory position, even in rules that have “spotting” included, whereby once placed on the table, units stay that way regardless of what happens to them or where they go. So “local” commanders in the shape of your metal alter ego’s, never lose sight of what’s happening as you can see everything for them.

To take just one example of why this matters. Napoleon is supposed to have seen the Prussian approach to Waterloo quite early on in the battle around 1:30pm just prior to D’Erlon’s attack. All he got was a fleeting glimpse with out knowing that he had already missed part of the force, who were by that time a lot nearer to his flank than those he had actually noticed but were already lost in dead ground. He was thereby unable to judge accurately the amount of time he had available to attack Wellington without undue interference.

To take just one example of why this matters. Napoleon is supposed to have seen the Prussian approach to Waterloo quite early on in the battle around 1:30pm just prior to D’Erlon’s attack. All he got was a fleeting glimpse with out knowing that he had already missed part of the force, who were by that time a lot nearer to his flank than those he had actually noticed but were already lost in dead ground. He was thereby unable to judge accurately the amount of time he had available to attack Wellington without undue interference.

Final Comments

That’s about all I have to say for the moment. These devices don’t take much time to make and I hope that you will not find them too rudimentary or old fashioned, for 21st Century wargames. Of course computer based games do this all for you and if played head to head can, in many ways, give a better idea of command problems than miniature gaming, or at least better than all but very well umpired games, that is.

However, you do miss out on the aesthetics of the tabletop game and the ability to blame the dice for your misfortune!

Most of the PC games I have had contact with seemed to contain some strange combat resolutions and some distinctly suspect A.I. Though I don’t doubt there has been, or will be, improvement in these areas and one-day playing head to head with only a map screen and state of the art, first person perspective graphics, will be the norm.

Having said that, I doubt it will catch on that quickly, if players were forced to take the back seat that real army commanders had, the inability to tinker with a hundred things they could not really have been aware of would drive them nuts!

Besides, the boredom of inactivity between decision points, if played in real time, would soon have them yearning for the good old days, when men were men and all they had to rely on were their wooden triangles!

David Commerford related his ideas and theories in “The Possibilities of Command” in the last issue of The Courier. In this article he demonstrates how his thoughts would work on the gaming table. We welcome any and all comments regarding these two articles. Send correspondence to the magazine at PO Box 1878, Brockton MA 02303. - Robert Hamper, Napoleonic Editor

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier # 89

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com