This also leads to considerations of whether or not a “game” is capable of reflecting “reality”, and, if so, whose “reality” does it portray? The question can also be asked of whether one’s opinion influences one’s historical interpretation based upon research or vice versa. This almost inevitably leads to two extreme statements of game design. The first being: “It’s just a game, so the situations and/or mechanics should be as abstract as possible”. The second is: “We may not know everything, but we should try to keep the situations/mechanics as historically faithful to what we think we do know.”

In this article I will try to avoid getting too deep into some of the philosophical questions I just posed (though it is important for any rules writer to be able to answer those questions for himself before he writes a set of rules). Instead, I will focus on some of the limitations that impose themselves on anyone who writes a set of miniatures rules. This means that any miniatures set forces the designer to start “with one hand tied behind his back” because there are some things he cannot escape from if he chooses to write rules for miniature wargames. Since my field is Napoleonics, I will use that era for any examples, but I think these points apply to all miniatures games (and probably beyond).

We must start with the fact that the miniature figurine is inanimate and static. In other words, it doesn’t make noise and it doesn’t move - all you can do is look at it! We can write reams of rules about skirmishing, movement rates, couriers, grand battery bombardments, routs and pursuits, all of which involve activity, but none of which can be carried out by our miniature figures. (If memory serves me right, years ago in the PW REVIEW Wally Simon wrote about a lead soldier named “Stumpy”. A good name for an immobile hunk of lead.) [See April, 1985 issue of Potomac Wargamers Review – available on Magweb. Ed]

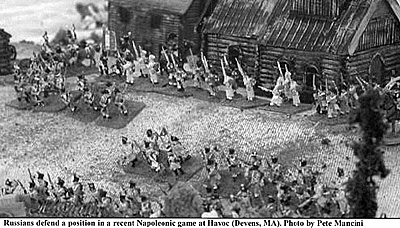

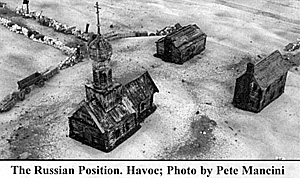

We can make the figures more fun to look at and we can put them in scenic locales. Like many others, I have always admired model railroaders who produce exquisite terrain for their trains, and modelers who produce beautiful miniature diorama. Duke Seifried can create wargame layouts that rival the scenery of other hobbies, and we all know wargamers whose painting techniques are so good that they could make even poor old Stumpy look like an Adonis.

Still, at that point, all we have is an aesthetic experience. They look good, but it is not yet a game, nor a challenge, a competition, or a learning experience. At this point, it is like a painting, a picture frozen in time. However, in a painting, your point-of-view has been determined by the artist. At a game table you can vary your view by moving yourself around, but you are still pretty much restricted to a 3rd person point of view, and due to the size of the toy soldiers, you will probably have a “helicopter” view of the whole table. Some games have used periscopes, hidden movement, or cameras to limit visibility, but the figures being observed are still all standing still.

This brings us to a second fact, which is that, the “game” or the “activity”, is all in our heads. Rules, lead figures, model terrain, cotton for smoke - all of these are symbols or tokens to spark our imaginations. The less intrusive, more consistent and coherent the rules are, the easier it is for the imagination to travel down the track in the direction the game designer wants it to go. The better the painting, the more breathtaking the terrain, the easier it is to “suspend disbelief” and to see, in the mind’s eye, Stumpy lowering his bayonet and advancing with the accompanying boom of artillery.

Interestingly enough, just as battle paintings tend to emphasize the heroic action or an epic panorama, so too do many wargames. That is, one does tend to imagine the waving banners, cheers, stirring music, heroic deaths and glorious victory with relative ease. It would be just as easy to write into a set of rules other more discordant images of painful death and waste which, while just as accurate, may not connect with a player’s expectations or his mental “image” of the battlefield the game is portraying. Missing that connection could disrupt the “suspension of disbelief” – in other words, some players get uncomfortable if the subject gets “too real” or “too serious”. Some players may also resent attempts by a designer to include rules that allow for high levels of variability or chance that may upset players’ plans.

I don’t mean to suggest that one should not include such rules. I am only pointing out that you need to know what you think is important and that you should be clear on the audience you want to appeal to. Appealing to the imagination of a large audience means tapping into some common perceptions of that audience. For miniatures gamers this usually means the history that they have read about, seen on TV or the wide screen, or have “learned” from other rules set or wargamers. If the designer already shares an historical interpretation, or a vision of what the events may have looked like, in common with the players of his game, it will be easier to write his rules. It is more likely that game mechanics that call to mind certain images for him will create a similar impression on the players.

The first organized group I ever participated in was organized and hosted by Dion Osika in Mountain View, California. (By the way, Dion was one of the most prodigious painters you’ve ever seen, and had a table, a room, and tons of 25mm figures. He was very generous to newcomers like me until we could get our own collections together). We used Fred Vietmeyer’s Column, Line, and Square rules. Eventually, I came up with my own historical interpretations and opinions on rules design, but in the meantime much of my “historical interpretation” or expectation of what was “Napoleonic” and what was not came directly from CL&S concepts. If I were to see another set of rules I might easily have said, ‘That’s unrealistic – that’s not how CL&S does it.” I’m not saying this to pass judgement on CL&S, but instead to illustrate how difficult it can be for a rules writer to get new ideas accepted by players if their vision differs from his.

So, we accept that the game is in the imagination and that when the figures are set up they create a snapshot good for recreating one moment of the battle. It then follows that there must be a reason for moving the figures around the table and then pausing to look at the new scene they now make. Otherwise, one would only need set up the figures in their “starting positions” (or even have left them on the shelf and stared at them) and then “imagined” the whole battle.

The miniatures themselves are merely representative game tokens whose job it is to spark changes in the scenes of our imaginations when placed in new positions on the tabletop. These scenes should more or less match those envisioned by other players. Thus, a new “scene” implies that the imaginary path a player has been going down may need to be changed. Placing figures in new positions is a way of giving information, or to be more precise, of visually illustrating new information. Even painting Stumpy’s coat solid blue, or giving him colored turnbacks, cuffs, shako plate and buttons are just two different levels of information for a viewing player. This may or may not be important, depending on how the rules use or ignore that information.

I might add that painted miniatures are not inherently “more realistic” than non-painted figures. That beautiful uniform can be a kick to look at, but it also represents just one concept, frozen in time, that may not be applicable to a new situation. Was this a brand-new regulation uniform that would look faded and different after two months of campaigning? Two years? The important thing to remember if you are designing miniatures rules is to give no more importance to the actual figures than they deserve. If the rules contain important concepts that can be conveyed by a figure’s paint job (say, shabby landwehr with low morale, or bear skinned grenadiers or guards with higher morale, or to identify specific troops to whom different rules apply), then take advantage of it. Otherwise, don’t bother and just enjoy them for their artistic merit.

Since miniatures are three-dimensional objects, they have some obvious limitations. The more realistic the terrain, the more that individual lead figures will fall over. That can be avoided by gluing figures on stands in-groups, but now they are less flexible in adapting to ground as “real” units would. They tend to be out of scale with the terrain, often being too tall, and their “columns”; “lines” and “squares” usually take up way too much ground.

The mistake to avoid here is allowing the miniature figure to dictate the rules rather than have the rules dictate the use of the figures. For example, suppose that we have a French battalion in line. In reality, it would be three or four yards deep, but is represented on the tabletop by figurines whose depth, according to the measurement scale of the game, cover 15 yards of the miniature terrain. It would be an error to use game calculations or measurements based on the physical figures. Instead, to avoid “unrealistic” distortion, the rules have to account for where the “real” battalion would have been and calculate accordingly.

I’ve seen some ridiculous domino-effect game situations where villages have been represented by model buildings (which were 50 yards high in scale). These could be occupied by a certain number of figure stands based upon the frontage of the stands. That distortion led to multiple stands being lined up down the road behind the village hundreds of yards away. This in turn caused other units to have to change positions to make room for the occupiers of the village hundreds of yards… well you get the point. None of it corresponded to any “real” village occupation. Remember, you can’t let the “tail” (figures) wag the “dog” (the rules). The miniature figures are there as game pieces or representational tokens for the rules to propel the illusion of movement and activity for player imaginations. If the figures themselves are to be the main concern, then use them where they show to their best advantage – in a diorama.

The lower level the game, the more distorted the miniatures can make a game. That is, the more that individual animation is represented, the less able a lead figure is to fill that role. For example, in a large Napoleonic game, thousands of men may be trying to maneuver in close-order formations. From a game design standpoint, these are coarser and less well articulated movements than those of an individual skirmisher.

Thus, the large formations are easier to approximate because they have a certain allowable margin-of-error which will still produce the game effects desired by the rules writer. The range of actions that the individual could make is much more varied and thus harder to illustrate by pushing around the lead soldier. The information conveyed by maneuvering the large troop of miniature lead bodies around the table is enough to progress the game forward, with less having to be left to the players’ imaginations. Moving Stumpy the skirmisher forward three inches, though, will not give enough information to the players. This puts the burden on the rules to provide other pieces of information in other ways to describe what Stumpy is doing.

This can be exacerbated because if Stumpy is the focus, the player needs to have a first-person point of view – see what Stumpy sees, hear what he hears, similar to role-playing games. This is difficult to do with lead figures and the rules must have mechanisms to simulate this. At higher command levels, where a general is a third-person observer of the bodies of men under his command, it is a little better suited to our lead soldiers and allows for more abstraction in the rules.

Thus, it is my contention that to create the best miniatures games, the rules writer needs to be aware of the limitations imposed by writing rules for miniatures games. Building rules around figures can make for very awkward games, but subordinating lead figures to the rules, as carriers of information to your imagination, might ease the task of the game designer. If that fails, then just roll a lot of dice!

Writing rules is in the lifeblood of every gamer. There is hardly a player or club out there who hasn’t concocted their own set let alone play with a pure, unaltered published one. Over the next few issues, the Napoleonic Editor will be presenting some articles discussing various aspects of game design. Several members of the Code Napoleon playtest team were asked to share their gaming experience with the readers.

We hope you find the articles helpful and informative. Please relay any comments to the Nap Editor at: campaigner92@yahoo.com. If you think you have something to say on this topic that would be of interest to others, let us know.

Ned Zuparko is well known in wargame circles. He is a former Napoleonic Editor of this magazine as well as a published rules writer in his own stead. He starts us off with a look at how rules designers are handicapped even before putting pen to paper. - Robert Hamper, Napoleonic Editor

A topic that often arises when discussing wargames rules is that of “playability” versus “realism” or sometimes as “fun” versus “simulation”. This might take the form of debating how much detail from historical research should be incorporated in the rules set, with it being understood that the more detail that is included, the more cumbersome the rules will be to play

A topic that often arises when discussing wargames rules is that of “playability” versus “realism” or sometimes as “fun” versus “simulation”. This might take the form of debating how much detail from historical research should be incorporated in the rules set, with it being understood that the more detail that is included, the more cumbersome the rules will be to play

Creating the next scene by moving the miniatures also implies a chronological game order or sequence for the player. That is, he will not confront a “new situation” until he has finished a “previous situation” that he found himself in. Since the miniatures themselves, as well as their positions, represent information, and if the rules say that that information will change over time based upon what had happened previously, then our miniature figures lend themselves well to marking the progress of a sequential series of events. A good rules writer will take advantage of that by limiting detail or information for players to just that necessary to advance the game to the next scene. Other details may be “historically accurate”, but if included will only bog down the game.

Creating the next scene by moving the miniatures also implies a chronological game order or sequence for the player. That is, he will not confront a “new situation” until he has finished a “previous situation” that he found himself in. Since the miniatures themselves, as well as their positions, represent information, and if the rules say that that information will change over time based upon what had happened previously, then our miniature figures lend themselves well to marking the progress of a sequential series of events. A good rules writer will take advantage of that by limiting detail or information for players to just that necessary to advance the game to the next scene. Other details may be “historically accurate”, but if included will only bog down the game.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #86

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com