This is a study in maps - an exercise in the confusion over maps. I got this idea in the mid 80’s and always thought there was a game in it, but only got around to writing it down now. It all began when a group of about 10 of us gamers went on a winter camping trip in a local state forest. We did this each year, and chose the winter because of the obvious -- lack of crowds, bugs, snakes, and Boy Scouts. We had the woods to ourselves - which was a good thing because fewer people were likely to get nicked by stray rounds.

One day we decided to conduct an experiment after arguing half the night before on the topic of movement rates of various troops on roads and across country. We each had topographic maps of the forest and decided that we would break up into three teams. Each team would make its way through the map from three pre-arranged starting points and and rendezvous on a distant (but not too distant) hill top that everyone could see. One team would start out on a paved road which, according to the map, went right over the hill. Another would begin about a mile away and work its way over a small hiking trail which another small scale map the park gave out showed going to the top and crossing the paved road. The third team was a mile beyond and would work its way to the top across country. So having planned it we were at our appointed “jump-off” points by 6 am.

Then Began the Slaughter of the Innocents

To avoid boring you with the excruciating details, the team on the road mistook an even more distant eminence for the objective, and completely overshot the mark. No road went over this further hill-top (which they thought was the hill-top they were supposed to be on, so they wandered around all day and were not heard of or seen all day till they came back to the cabin that night.

The group following the trail got side-tracked to another trail (not shown on the map) and wandered around. They eventually got to the hill-top, but decided they must be on the wrong one, and back-tracked and tried again. Eventually they came back to the same place and decided then that they must after all be on the right hill-top. They never saw either of the other two parties till they got back to the cabin.

As it turned out the group working its way overland got there relatively easy, but since they were met by neither group, decided that the other groups must have gotten there already and gone back to the cabin, and so they then decided to go to the cabin and play war games. A few minutes later the “path” group showed up.

What had started as an exercise in movement ended in a demonstration of confusion over maps.

The interesting thing was that all groups had identical up-to date topographical maps of the National Geodesic Survey s which showed fairly good ground detail and were fairly up to date. All the members had extensive training in maps from the scouts or from ROTC. (I know.. same thing.) One wonders how then commanders in former ages managed to find anything!

This game thus is a game about maps, or more properly the confusion that erroneous maps can cause.

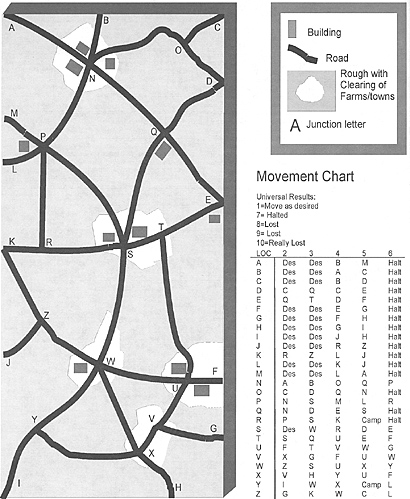

The table top AND the map each player has is shown in Illustration A. The terrain is very rough and is a combination of heavy woods, rocks, swamp, scrub small hills and gullies over most of its surface. All shaded areas are rough. The exact composition is up to you. Those areas marked by clearings are not rough and resemble more normal terrain.. The table top is criss-crossed by a network of poor secondary roads.

2. You don’t have a copy of the real map!

3. There is nothing you can do to get a copy of the real map! The scenario is a peculiar one in that unlike your real life counterpart not only will you be able to feel and experience the frustration of being lost and not knowing what to do, but you will be able to SEE the total effects of this on all your contingents as they stumble around the field. Remember this is a scenario to portray chaos on a large scale. An umpire is almost essential to resolve differences and facilitate the game.

The terrain need not be complex. In fact, it will work much better if it is simple - entirely stylized! You can put a few hills here and there to represent elevations, and a few trees for effect, but really all you need to do is assume the entire table is tree covered except for those areas marked as clearings, and those can be shown by cut-outs of construction paper in light green as opposed to dark green. Roads can be simple construction paper and the buildings can be your regular buildings. The key to the game is not in the terrain, but in portraying the situation in an air of unreality, or rather, like a strange through-the-looking-glass world where things are not always what they seem.

The forces for the game are pretty much entirely up to you, but the game is predicated on the “movement” of forces onto and around the table top, that is groping for each other and the enemy in an area where they are completely unfamiliar with the terrain and have limited intelligence. Ideally there should probably be four or five “groups” of forces on a side, and each group should enter from a different entry point on the edge of the table. You can allow players to chose entry points for each group (and each group must have a different entry point) as well as the times they enter on. On the other hand you could dice for them, that is, say, rolling a 20 sided die for one of the entry points and a six sided die for the turn it enters on. It is up to you. Note that there are 13 entry points on the map, and an “A” could correspond with 1 etc. The last 7 (14 to 20) roll again.

Each “force” should be small, no more than three or four units, because, remember, we are dealing with a compressed area. More of this anon.

The period chosen would be excellent for the modern period, or just as good for earlier periods like the French and Indian Wars, colonial conflicts, the Medieval period, or any period where one side or the other carried on a “war of detachments.” That is a small war of small forces.

Thus rules you use should be fairly simply as a lot of chaotic things will happen. They should also have rather short firing ranges given the size of the table top. Note that this is only a scenario creator, and not a whole rule set of itself. It is a game idea which can be modified as needed.

Forces, until they deploy and come into contact , move along the roads from lettered junction to lettered junction. Each time a player wishes to move a force he states what junction he wishes to move to and rolls one ten sided die. If he rolls a 1 he moves to the junction as desired. If he rolls a 7, it means he his halted, which means he cannot move this turn. and remains at the location he began with. If he rolls an 8 it means he is camped and cannot move again until he breaks camp by rolling a 8,9, or 10, on a 10 sided die, or the location he is in is entered by another friendly or enemy force. If he rolls an 9 it means he is lost. This means that he cannot move for this turn or any turn until he “unloses” himself by rolling an 8,9, or 10, on a 10 sided die.

While this is happening he is NOWHERE on the field! and it is possible that an enemy force could move right through his junction! If he is “unlost” he comes back to the same junction. If he rolls a 10 this means that he is REALLY lost and will not be on the field at all until he rolls an 8,9, or 10 on a 10 sided die, at which time he re-enters the field by any entry point he chooses. If this is not to your liking you can have it that the player must randomly re-enter at any of the junctions surrounding the open areas around him. Thus, if a player at Q is REALLY LOST he might have to roll a die and could turn up at E,T,S,P,N,O, or D, which are all the junctions bordering areas touching Q. Note that there is no direct path from P to Q or from O to Q, or from T to Q. In this case it is assumed he has been “wandering in the woods.”

All the other cases show the result on the chart. So, assume a player has a force in I. He can ONLY chose Y as his intended move. So if he rolled a 2 or a 3, he would go there, but if he rolled a 4 he would wind up at J and if a 5 at H. All the others have the dire results as shown.

Friendly and enemy forces are in “contact” only when they are on the same location or junction. Movement between junctions is instantaneous and represents a length of time. You will have to determine this length of time according to your table top rules so you can tell how many game turns elapse before a major move where players get to move from one junction to another.

Once enemy forces come into contact at the same junction, a battle occurs. The side who was there first holds the junction and any buildings, and the enemy may try to dislodge him or retreat. Deployment should be centered on the roads.

Space is considered “compressed” here and there are much longer distances between junctions than correspond to the table top distance. Assume there are opposing forces fighting at W and others at Z. On the table top the lines may come very close to each other, perhaps touch but that in no sense means they are one battle! In this case the umpire may decide if they become one battle, but that is not necessarily so. Thus the right flank of one Brobdignagian contingent at W may touch the left of another Brobdignagian contingent at Z, but that does not mean they are in contact. Indeed, the right of a Brobdignagian contingent at W may touch the left of a Lilliputian contingent at Z!) but that does not mean there is combat! The two forces may be far apart. Remember, everything centers on the junction! The action may become so large, however that the umpire may rule differently.

The exception to this are the clearings with S &T, U&F and X and V. Troops in one or the other are aware of enemy or friends in the one or the other, and it can be one big battle!

The biggest task of the umpire will be to ‘vector” the forces towards the junctions. For example. Assume there is a Brobdignagian force in S, and a Lilliputian force in T. The Lilliputian commander may try and elongate his line in an attempt to squirm into Q or U, and the umpire will have to pull him up short and tell him that he must redirect his movement against S. Likewise a Lilliputian force in P is attacked by a Brobdignagian force from S. The umpire will rule that the Brobdignagians set up say 12” from P and start their battle from there.

The Brobdignagian however begins moving in the direction of “R” claiming he is making a “wide turning movement.” -- uh-uh. The umpire has him decide to either attack the Lilliputians at P or move back to S. Thus, the actual inch distance from W to Z or S to R does not matter, it is that each little contact “centers” on its road junction.

As the game progresses however and two or three forces come together the umpire may allow battle (as in the Wilderness) to become more general.

Note: All forces remain “brigaded together” and move separately, even if on the same junction. Thus, assume that two Lilliputian forces are in T and both wish to move to S. Each must move separately.

Critics can rightly argue “THIS IS ALL LUCK!” - and so it is. In wildly chaotic situations like the Wilderness or the Heurtgen forest very little goes according to plan and genius has little input. Much will be how well you can opportunisticly take advantage of the situation. Further, the umpire must be of a strong character. He will be far more than a “hidden-movement” coordinator or an arbiter of arguments. He will very much be like the senior officers in command exercises where the inputs of various players are submitted to him and he makes the decisions based on his reading of the situation, his experience, and judgement.

This is the map. Now... a few of the most basic rules of the scenario.

This is the map. Now... a few of the most basic rules of the scenario.

1. The map is wrong.

GENERAL GAME PARAMETERS

HOW THE GAME WORKS

CONTACT

THE IDEA OF COMPRESSED SPACE

NOTES TO THE UMPIRE

A FEW CLOSING WORDS

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #84

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com