This isn’t an article about tactics or strategy, or about how to get other players on the same side to do what you want. It is about the various methods you can use to decide what happens when two bodies of troops interact with each other on the table top.

Many actions in the game require decisions. These are actions where the possible outcome is either not always clear, or within the will of the players. Here some artificial and arbitrary means must be devised to take the place of human (or divine) volition. A player who says “I will move my infantry 12 inches forward”, and there is no opposition, or who in a move-countermove game elects to move second, is making a decision, but he does that for his own reason and of his own will. If, however, the same player declares he will move his infantry 12 inches forward but there is an enemy unit in the path, he cannot simply say “I will move my infantry 12 inches forward, and rout the infantry and continue my move. Here a decision method is required.

Now there are many types and means of making decisions, and we will get into some of them, but the first and most important is to understand what is happening. In the case above the person whose infantry is in the way would like to say, “My infantry will stand fast and repel the enemy.”Obviously there is a difference of opinion. What first must be decided is all the possible outcomes of the encounter between the two troops that we wish to model. There is for any situation a huge, if not infinite set of possible detailed outcomes, but we probably would not like to model allof them (though it seems some rules do try!). The more we model the more interesting and colorful the game may be, but there soon reaches a point of diminishing returns. The multiplication of outcomes becomes cumbersome and detracts from the enjoyment of the game. Let’s take the most simple of decision methods. A Heads I win Tales you win. -Simple and direct, but what, might I ask, is the “content” of “winning” or “ losing.” This is not as jejune as it sounds. Most gamers never think in specific situations on the table top what winning or losing means. I don’t mean winning or losing the entire battle, but who wins or loses in the disagreement of opinion of the gamers above, how do they win or lose, and what that means. Obviously if we were to accept total annihilation of the loser and the victor gets off without a scratch, coin tossing is the neatest and most elegant means. If we want more we could result to multiple coin tosses for example, toss again to see if eliminated or casualties, then again to see if heavy or light casualties and so forth. Here is the first case of where it would become cumbersome.

To make any sort of interesting or variable outcome, there would have to be a large number of coin tosses. The next more complex method would be to use a dice roll to embrace several outcomes in one toss.

Obviously you could further elaborate this to multiple rolls etc., and this is the path most rules take. For example in most modern games you check the gun firing versus the armor, roll for range, roll for shell, roll for penetration, roll for area penetrated, roll for damage and so forth. Now one thing must be emphasized; both methods so far are entirely adequate if you are not demanding of more sophistication. Both will produce a decision out of control of either interested players and achieved by a random means. Both however have limitations as to their method, and to their application. It is with the various types or “vehicles” for decision making that I now wish to deal, and general describe them by capability, options, and quirks

THIRD PARTY INTERVENTION

Using a third, uninterested or semi-interested party, in some sense an umpire who observes the situation, makes a determination by his own logic or opinions and pronounces a result. Perhaps the easiest of them all, wargames were once run entirely by umpires, and it was, I am told, the practice in England to hold TEWT (Tactical Exercise Without Troops) which had the players interacting with the umpire. In role playing games he is a Gamemaster. The benefits are that you really need no rules, and the results can be rich, varied and adventuresome. The drawback is in finding a disinterested umpire who wishes to put his skin on the line. Another drawback is also one of its strengths.

Results can be too varied and players lose a certain predictability of result. This is exacerbated by the tendency of umpires to try to be creative as a positive input in the game, and they soon go overboard. After all, in most games the umpire really has nothing to do except stand around and make trouble.

NON RANDOM ITERATION

This is simply a means of producing results upon calculation of observed criteria along an algorithmic path. Sounds complex, but it really is just a simple step program of objective evaluation. Some of the early wargames (HG Wells’ and others) used methods like this. An example would be that of our two infantry forces above would yield a rule like this. “When two infantry forces come together the stronger one defeats the enemy and causes 50% casualties to the defeated side and itself suffers 50% of what the loser lost.” Thus 20 men attacking 16 would cause the loser to lose 8 men and the attacker 4. You can play with the values up and down, but as long as you don’t enter a random factor, it’s a case of what you see is what you get.

The advantage is that it is straight, simple, direct, and unambiguous, the disadvantage of course is that it is obvious who will win. Games with extensive use of rules like this acquire a “chess-like” quality about them and become simply “counting games.” One interesting way around the problem (which I have never seen tried anywhere) is to introduce not a random but a hidden multiplier, factor or “kicker” to the game. This involves either the use of a roster system where the numbers of the units may be different than the number of figures on the stand, and hence neither the defender nor attacker may know who is superior, or the use of troop value points which are not revealed until it is called into play. It now becomes interesting to decide what happens further. Are casualties scored by men or by “men times points?” Of course, once the troops are revealed there is no longer any surprise, and the game goes back to a counting game, but it is a means to liven up what seems a dead-end method.

RANDOM ITERATION

This method is the most common and is simply a random number generating machine, dice (of whatever face and number), coin tosses, stock market quotes, or a real random number generating machine like a computer. All of these are simply versions which require a number or result to be generated which is outside both the control and the knowledge of the players. I won’t go into much detail as we all are familiar with these, including ways to “tweak” the system by modifiers, average dice, means, and so forth. Iteration here, and in the non-random type, means essentially “if this, then that.” It is merely providing a list of outcomes and a way of choosing among them. The strengths of this system are its good blend of simplicity and functionality with a good range of choices possible using several die rolls or combinations of dice. Here of course the key is the die size and number and the probabilities when they become additive. These can be uniary (that is one die roll by one player or each player for his side); binary (both players roll die and compare the result in some way, or “N”ary which is other dice rolled for terrain or other factors. The drawback to this system is that at its simplest level you get “N” results where “N” is the number of faces on the dice and possibilities greater than that requires successive rolls or larger and larger numbers of die faces. These are not always as easy to use as one might think! D20 dice are hard to read and never seem to stop rolling! D6s offer a limited number of possibilities but these are so few in number that the charts can usually be easily committed to memory.

In all cases the die roll must be matched with a chart or table. In more complex systems then, the larger the number of faces, the larger the table and the more iterations (die rolls) the more possible results and the complexity exponentiates. Thus, if you use a 6 sided die and make 2 rolls, one to see the general result and another the more specific you are soon talking about 36 possible results. Make it three die rolls and it is 192! One feature of dice that I have rarely seen is “result dice”. That is, special purpose dice with faces marked for results. I once acquired a quantity of blank dice and painted colored faces on some of them to represent the combat results of the game. They were and I made one face black for eliminated, one yellow for broken, and one green for disorganized. One other face was red, and the rest were unmarked. In melee, the black, yellow, and green were used but the red counted as a white face. In fire the red counted as material damage while the green simply as disorganized.

It worked well, but the problem was that that set of rules had other provisions which required numbers and it became too cumbersome. Of course the problem is that there are only a limited amount of results, and this soon became inadequate. One could multiply the faces, but again the colors and probabilities change the more complex you make it.

EQUALIZED RANDOM ITERATION

I have never seen this used, but I note it as a possibility. Actually it’s a neat way to shut up the gamer in the group who is always moaning that his best pains and immaculate generalship is spoiled by bad dice rolls. The central feature is that each player is given a list of “die rolls.” The best way to handle this is to simply scrawl numbers on small pieces of cardboard (about 1/2” by 1/2” and put them in a deep box.

Each player has his own and when he needs a die roll he draws a chit from the box and that’s his roll. The advantage is that since both boxes are equal with the same number of 1’s, 2’s and so forth, each player will get, the same “magazine of luck.” Of course the order they are drawn in is still random, and if the game is shorter or longer, random factors of luck will still impinge, but if you do not make the nubers of chits large, say only 20 or so, you will be sure to deplete the box before the end of the game and each player will get at least one pass of equalized, though random, results. When the box is finished you simply dump the chits back in, shake, and continue. Of course the importance of the die roll cannot be weighted and getting a “6” on an innocuous roll will not compensate for a 1 on a more serious decision, but these too should level out. By the way, the player will still complain about his bad luck.

A modification of this is to give the players a printed list of results. These again are in random order, but of course the same number of outcomes appear on each list. Players then can chose which action to apply the next die roll to. For example, if a player has the following numbers in sequence 1,5,3,2,6, he may chose to resolve his actions in such a way that the first action he resolves is a trivial re„ammunitioning of a unit in a rear area that he doesn’t care about, then go on to rally a unit in a critical position using the five, taking the two long„range fires next where he doesn’t care too much about the result, but saving the all„important six, for the critical assault on a redoubt, which he does next. It is a little wierd to understand, but it yields rather good results in a game.Ì

COMPARATIVE ITERATION

Basically this is the same as dice except it relies upon both players’ choosing a number or a category and comparing the result. This is commonly called a “matrix” and in some ways is an elaboration of the “scissors-paper-stone” game. A good example of this was part of the combat results table in Avalon Hill’s game Each side secretly picked a card from a set of six battle tactics. The tactics were then cross referenced to a table which gave a modifier to the die roll. If, for example, you as the British chose FRONTAL ASSAULT and the Americans chose STAND AND DEFEND, the modifier went drastically against the British. If on the other hand the Americans chose something else the result would be opposite. In this game, as I said, it modified a die roll. In another Avalon Hill Game, the much maligned KRIEGSPIEL, it was pure comparative iteration without the die roll. The game came out at the worst possible time for its type, when games were becoming more complex and detailed and it was a simple abstract game of war. This was the time when SPI and others were publishing monster games of Russian Front battles with thousands of units representing everything right down to the 443rd SS Volksturmpanzergrenadier mess-kit repair company, and KRIEGSPIEL with itssystem, board and minimalist rules seemed quaint and silly. It actually was a very good game and had a lot of innovative ideas. But then again Joubert was probably a better general than Napoleon but he was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Yet comparative Iteration suffers from one big drawback which was noted by reviewers. Unless carefully crafted, the tables can become predictable and one result favored over others over the long haul. The bigger problem is that the game becomes a “will-he/won’t„he” game. Players sit there agonizing which choice to pick and try to out-guess their opponent. This tends to burn up game time fast. Still, there are three big things going for it. The first of course is that it is diceless, the second that it can offer an easy, wide range of results, and the third that it DOES reward good tactics! One way to get more mileage out of it might be to limit results that can be used depending on the situation on the table top. This was not possible in KRIEGSPIEL.

But it might make it more interesting if out of the possible actions of Charge, Move, Fire at will, Rally, Volley Fire, and so forth, say a unit in column could only Move or Charge, where a unit in line could do Move, Fire at will, Rally, or Volley fire, where a unit in extended line could only Move or Fire at Will, (but not use the more devastating Volley fire) but might be able to take advantage of Cover. A lot of this has been subsumed into “orders” and troop actions in games rather than direct combat decisions, but it might be worth-while to reconsider moving them back again.

DIRECT OUTCOME

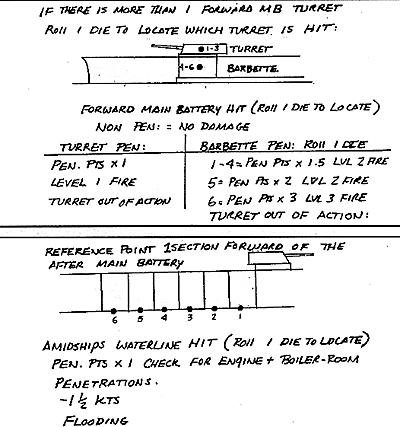

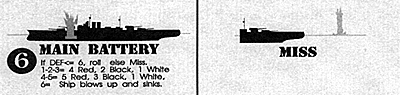

I have chosen to show you much, older version of the type of card Terry uses, which I had in my archives because I wanted to show you how cards could be handmade and also quite detailed and attractive. Terry has since gone on to a slightly modified system, and a much more professional artwork presentation (he is an award winning free„lance grahics artist). Terry used the Jane’s fighting ships framing displays in his games, and this is a good example of how cards can easily be hooked into other mediums.

The advantage to cards is that a lot more information and detailed cases can be inscripted on the cards and the number and frequency of the card takes the place of a random event. The other is that the card can itself be a “miniature chart” and in effect, you don’t have to look up the chart, it’s looked up for you! Thus, take the aforementioned BATTLEFLEET- The card, besides having a small generalized picture of mayhem and destruction on it, also has a dice roll showing what happens if the shell penetrates and another if it doesn’t. It is a neat and nifty tool and speeds up the game. In an example from my own table-top gaming system, I use a set of cards more of the “chance” card variety which gives all sorts of events. Cards can also be used in new and creative ways.

For example, in my own set of wargame rules (akin to Battlefleet) called ADMIRALTY, some cards specify hits of duration, that is that a ship is disabled for a certain time underneath the ship and it moves with it as a marker until it is rolled off or expired in which case it returns to the deck. One other factor in cards is the method of use. In BATTLEFLEET and ADMIRALTY the card deck is shuffled before picking for a firing ship. In my table-top cards the deck is not, and cards turned up are sent to the discard pile. Here the trick is determining the probabilities for each hit or action out of the whole range of them and drawing up the requisite number of cards. Here the use determines the probability. In the “reshuffle before each fire” system, it is theoretically possible to have a critical hit occur each time.

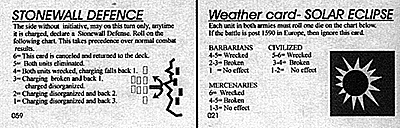

In the “chance card” method, (more akin to the “Get out of Jail Free” card of monopoly) which I employ in my tabletop land battles, you have not only a limited possibility, but also a drastic change in the probability once a card is drawn. Let’s take a card like “Stonewall Defense” of which there are four in the deck of 120.

However, since the games last only 5 or 6 turns this means there is only an 11.9% chance that another stonewall defense card will be drawn! Not odds that are likely, but not vanishingly small either. On the other hand, there is only one “Solar Eclipse Card” in the deck so there is only a .8% chance of that being drawn on any one turn and only a 5% chance that it will be drawn on any of the 6 turns of the game. Further, the classification of a “weather card” also has a particular meaning.

If any other type of weather card is already in play (snow, rain, heavy rain etc.) this card does not take place (the solar eclipse) but merely ends the other weather condition. The possibilities of cards are highly intriguing and they are great fun to draw, design and use. The problem with them is that they take some time to make up, and you will have to work carefully to craft the percentages. The big advantage to cards is they can provide unique, interesting , and exciting situations and results, simply because they are so open ended. They can manage a huge range of outcomes best. They can do this in one stroke where you might have to have dozens of charts and tables and complex rules and conditions using other decision making options. The drawback is that they are not good for quick repetitive results. They are good where the likelihood of any specific outcome is relatively small, and the likelihood of one event over another not too different. But when you get into larger groups of outcomes, other systems are better.

For example, having a deck of 120 cards wherein one result has 20 cards, another 30, another 40 and three others groups of ten, is probably a waste, and dice would be better! One other wrinkle with cards is the use of two decks. The first deck, of about 100 cards and many repeats. These are then shuffled thoroughly and a smaller deck of say 20 or so is dealt for the game. Thus the odds of any card in the large deck remain the same, but the odds and outcomes of the cards in the smaller deck may vary greatly, moreover, will vary from game to game.

The means of decision making in wargames is, as you can see, highly varied and nuanced, and given your predisposition can yield wildly different outcomes and courses of actions. Very much will depend on the vehicle you use and the way it is implemented. Rules designers all too often fail to take advantage of them and simply, and unimaginatively, say “take a dice and roll it.” That may not be the best way to go considering what you want to model.

In fact you may be letting yourself in for a lot of grief and doom in what might be a great idea or rule system by saddling it to an inefficient decision making process. The key to success is carefully evaluating any decision procedure by the criteria of the following: “What general results are possible? How probable was it that any specific one happened in real life? What is the cut-off of allowable outcomes (how many are too small to be significant or worth the trouble)? And how often in the whole range of events could or do we wish this to happen.? Units could make several “Stonewall Defenses” on a single „ but two plagues of Biblical Proportions are hardly likely! Let me give you an example. The results from firing are pretty simple and relatively few. The target is either missed, or the target “fall down go boom.” Add a disorganization or two and some retreats, add on a terrain factor and you have an action tailor made for a random iteration (dice). Factoring in weather or stonewall defenses is probably better as a direct result (cards). Good luck and happy iteration.

1 Defender gets badly trashed.

2. Defender gets only partly trashed.

3. Defender and attacker get partly trashed.

4. Nobody gets trashed.

5. Attacker gets partly trashed.

6. Attacker gets badly trashed. Put simply: cards. Cards offer one of the more seductive, yet elusive means of wargame decision making. By cards I don’t mean a deck of playing cards. That is simply another random iteration method. The deck of cards produces a random number (or two types if you differentiate faces from suits) and you still have to apply it to a list. I mean results that are printed directly on cards, like the “Go to Jail, Go Directly to Jail, Do not Pass Go, Do not collect $200” cards in Monopoly. This type of card is only now beginning to come into games in a small way, spurred on by the bloom in desk-top publishing which allows players to make custom cards and artwork. Cards can be more or less of two types, either the “chance card” type or the “weighted results” type. Chance card types are like the “ Get out of Jail Free” cards or “go back one space” from popular games, while “weighted results” give certain ranges of results. An example of the latter is Terry Manton’s BATTLEFLEET where the “hit deck” shows where a shell has landed on a ship and you then reference armor and gun to test penetration and so forth.

Put simply: cards. Cards offer one of the more seductive, yet elusive means of wargame decision making. By cards I don’t mean a deck of playing cards. That is simply another random iteration method. The deck of cards produces a random number (or two types if you differentiate faces from suits) and you still have to apply it to a list. I mean results that are printed directly on cards, like the “Go to Jail, Go Directly to Jail, Do not Pass Go, Do not collect $200” cards in Monopoly. This type of card is only now beginning to come into games in a small way, spurred on by the bloom in desk-top publishing which allows players to make custom cards and artwork. Cards can be more or less of two types, either the “chance card” type or the “weighted results” type. Chance card types are like the “ Get out of Jail Free” cards or “go back one space” from popular games, while “weighted results” give certain ranges of results. An example of the latter is Terry Manton’s BATTLEFLEET where the “hit deck” shows where a shell has landed on a ship and you then reference armor and gun to test penetration and so forth.

Below is my own ADMIRALTY system which simply gives you the data and possibilities in one shot. In both systems a ship got a number of draws from the deck depending on its broadside and range. Most of the deck was a “miss” but some where hits. I have shown you the most devastating of them.

Below is my own ADMIRALTY system which simply gives you the data and possibilities in one shot. In both systems a ship got a number of draws from the deck depending on its broadside and range. Most of the deck was a “miss” but some where hits. I have shown you the most devastating of them.

Since there are only four, that any one of these will be drawn is 3%. If the first card of the game is a “Stonewall” card , then that means there are now 3 stonewall defense cards left out of 119 or 2.5%.

Since there are only four, that any one of these will be drawn is 3%. If the first card of the game is a “Stonewall” card , then that means there are now 3 stonewall defense cards left out of 119 or 2.5%.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #80

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com