"Man of War" has been designed as a rule set suitable for reproducing squadron and fleet sized engagements with an emphasis upon command and control, real weather effects, and seamanship (sailing technique). Items such as individual crew assignments were blended into various game mechanisms for the sake of faster play and less book-keeping This scenario was an experiment to explore the accuracy and efficiency of the rules in a small scale frigate action. The scenario, of course, was based upon the famous engagement between the above-mentioned ships off the coast of Valparaiso, Chile in 1814. In the historical event, the USS Essex was forced to fight in a crippled state, having had her main topmast taken overboard by a squall just prior to the battle, and was captured by the British after a long, bloody, one-sided struggle. This game scenario, on the other hand, was designed around the supposition that Essex was able to fight in a fully fit state and it yielded an interesting and different result. The balance of forces was more or less historical. HMS Phoebe was a 900 ton 36 gun frigate armed with long 18's and 32 lbr carronades. HMS Cherub was a 500 ton 18 gun post ship armed exclusively with 32 lbr carronades. USS Essex was an 800 ton 32 gun frigate with a very powerful 32 lbr carronade armament and a token few 12 lbr long guns. With respect to speed, Essex and Cherub were equally fast, while HMS Phoebe was slightly slower. Essex and Phoebe had veteran crews. Cherub had a trained crew. All crews were rated with high morale. In game terms:

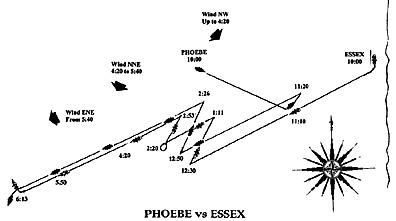

In terms of the rules, tonnage functions as a measure of not only the size of the ship, but also the relative size of its crew, and its ability to absorb damage. Gun factors are a proportional representation of the weight of broadside. Long guns and carronade factor are considered separately, with carronades restricted in range. The speed rating represents the maximum possible speed of a ship under ideal wind conditions. For game purposes, a ship with a higher speed rating will normally be faster under all wind conditions than another ship with a lower speed rating. Such apparently small differences in speed between ships can have great influence over the course of a game. Crew quality represents the ability of a ship to execute any function or task such as commence a turn or a tack, make or reduce or back sail, and so on. A veteran crew has a 5/6 chance to perform a given task on the desired turn; a trained crew will have a 4/6 chance; poor and raw crews are worse still, at 3/6 and 2/6 chance respectively. Crew quality likewise governs broadside rate of fire. A ship with a full veteran crew complement can fire a broadside every second turn, a trained crew every third turn, poor and ray crews every fourth and fifth turns respectively. Morale is considered as a feature separate and distinct from training, in view of the fact that even poorly trained crews can be inspired to great sacrifice by patriotic or revolutionary fervor. Crews with high morale are very resilient and must be beaten into silence before they will surrender. At the other extreme, crews with low morale are very brittle and are liable to give up the fight at the slightest excuse. Crews of average morale can be relied upon to fight well, but not to an extremity. In general, veteran crews enjoy high morale, trained and poor crews might possess either high or average morale, while raw crews are typically of low morale. In this particular scenario, both sides enjoyed solid morale and well trained crews. The length of the game table was oriented upon a north/south axis. The entire eastern table edge was considered to be coastal shoals, as was the adjacent half of the northern table edge. Any ship exiting the table along those edges would be considered to have gone aground. Weather was then diced for, resulting in a Wind Factor 2 light breeze blowing out of the NW, which favored the British player. USS Essex began play 400 yards from the mid-point of the eastern table edge to start play under full sail on a south heading. Nine different weather conditions (wind factors) are recognized in the rules, ranging from 0 (Calm) to 7 (Gale). The rules assume that it is impossible to fight in worse wind conditions. Various special effects, such as reduced gunnery effectiveness or the need to close lower gun tiers are associated with certain Wind Factors. An effort has also been made to reflect a more realistic weather dynamic. For example, if the weather is deemed to be worsening, the wind will show a tendency to increase in strength over the course of a game. Changes in wind direction will also exhibit a general trend, either veering or backing over time. In certain circumstances, a change in wind strength and/or direction can decisively influence the outcome of an engagement. A late change in wind direction influenced this battle. The British player was permitted to set on his ship(s) anywhere within 400 yards of the western table edge after weather conditions and the American start position had been determined. However, the British commander had also to deal with a special scenario condition. If the British player chose to use both his ships, the American player was given the option of attempting flight and could achieve a minor victory by successfully doing so. Certain conditions had to be satisfied in order to claim successful flight: (1) Essex had to have obtained a position either north, south, or west of any and all pursuers; (2) Essex had to be beyond gun range (1200 yards) of any pursuer; (3) Essex had to be faster than any pursuer. If all three conditions were met, Essex could claim successful flight. On the other hand the Essex was honor-bound to meet her opponent in battle, if the British player chose to commit only one ship to battle. The decision to commit one or both ships weighed heavily on the British commander. He knew Essex to be slightly faster than Phoebe, his strongest ship, and there was always some possibility that Essex might be able to escape by virtue of an untimely wind shift or a mis-step in British maneuvering. Victory conditions were as follows: The scenario conditions were purposely designed to put the British commander on the horns of a dilemma. Employment both British ships would confer a great gun power advantage over their single American opponent, but demanded a very careful approach to battle by the British ships. Essex was starting the game trapped against the coast, but a British maneuver miscue or an untimely wind shift might give her an opening to escape. In the end, the British player chose to leave his small ship Cherub out of the fight and thereby ensure commitment of the American ship to a battle. He would rely upon his favorable wind position and the long range guns of Phoebe to counteract a slight inferiority in speed. The British player started Phoebe on an easterly heading from a start point approximately one and a half miles west of the start point of the Essex. An historical game start time of 10:00 AM was mutually agreed. Essex immediately came to a WSW close-hauled heading beating to windward at about 3-1/2 knots under battle sail, knowing that her only chance of success was to seize the wind advantage and force action within the short range of her powerful carronade battery. If Phoebe were able to hold the wind advantage, she would be able to keep the fight at long range and Essex would be effectively helpless. Phoebe, with double-shotted broadsides held in reserve, boldly approached from the west on an ESE heading making about 4-1/2 knots under battle sail on a quarter reach. The range closed rapidly. At 11:10 Phoebe came to a NE heading and discharged her double-shotted starboard broadside within musket shot range (200 yards) at the masts and rigging of the passing Essex, hoping to cripple her aloft. Both long guns and carronades belched fire. Three six-sided gunnery dice flew from the British player's hand and came up as triple 2's - a possible critical hit on the very first fire! Then the range was checked for double-shotted fire and it was discovered that Phoebe had slightly mis-judged the distance and fallen into the -2 double-shotted range zone. No damage! Essex replied a minute later with her own starboard broadside of single-shotted carronades, firing low and inflicting minor damage to the hull and rigging of Phoebe.

Gunnery under the "Man of War" rules is conducted as follows. Three six sided dice are thrown, two of one color and the third of a different color. Each die is modified for any range and weather penalties. The two commonly colored dice are added together; the gun factor is multiplied by their total and the product is divided by 10 (shades of CLS) to obtain the number of hits on the point of aim, either the hull or aloft. The third die is applied in similar fashion to that part of the target ship which was not the point of aim. Point of aim can either be the hull or aloft. Fire may be directed at the hull, depending upon crew quality of the firing ship, range, and wind conditions. Otherwise MUST be directed aloft at masts, sails, and rigging. Fire effect is greatest within Pistol Shot distance (less than 100 yards). Carronades are effective up to Musket Shot distance (less than 300 yards). Hulling fire may be conducted by trained and veteran crews up to Point Blank distance (less than 600 yards) in good weather. Range then extends through Cannon Shot (less than 900 yards) out to a maximum range of Random shot (<1200 yards). Carronades are treated simply as additional gun factors within their range of effectiveness. Ammunition options include double-shotting and dismantling shot. Both options offer increased damage effect upon the target, but do so at lesser ranges. A full rake will generally triple any damage effect upon the target. In addition, oblique fire gives a fifty percent increase in damage effect in cases where gunfire is delivered from an angle greater than 45 degrees off the beam of the target ship. Neither a rake nor oblique fire will increase the likelihood of hitting, only the degree of damage. Whenever the three gunnery dice come up triples and hull damage is inflicted, a critical may be suffered. Gunnery hits upon the hull progressively reduce gun factors, morale as a function of increasing crew casualties, and also injure lower masts. Gunnery hits aloft progressively reduce speed as a result of shredded sails, parted rigging and lost yards and spars; If certain critical yards and spars are lost, the ship may become unmanageable and unable to tack or even move. As the two ships passed, the Essex kept on her close-hauled heading and revealed her desire to gain the wind advantage. In reply, Phoebe tacked at 11:13 and came to a parallel WSW course. Both ships increased sail and continued a very long beat to windward until 12:30, when Essex tacked and came to a close-hauled NNE heading. Around 12:40, Essex again passed under the lee of Phoebe and both ships now exchanged their port broadsides. On this occasion, the range was closer, the dice were a little better, and Phoebe's double-shotted broadside succeeded in inflicting modest damage upon Essex aloft, injuring the mizzen topmast. Essex persisted in single-shotted fire in order to maximize accuracy. Her return fire added to the hull damage of Phoebe and injured her lower mainmast. At 12:40 the wind fell to Wind Factor 1, still blowing out of the NW. At around 12:50, Phoebe, still holding the wind advantage, tacked to parallel Essex on a NNW close-hauled heading. Essex tacked in reply at 1:11. At 1:32 Essex again passed under the lee of Phoebe. In the exchange of broadsides, Phoebe had her jib boom shot away by an unlucky hit and Essex lost more sails and rigging to the high fire of the British. Both ships lost speed as a result, but Essex retained her slight speed advantage. The failure of Essex to gain the wind advantage was very frustrating. The American commander put the blame down to a poor steersman who had not kept his course close enough to the wind. After this exchange of fire, both ships continued upon opposite tacks for nearly an hour. At 2:20 Essex decided to try wearing around instead of tacking. Tacking was a lengthy process in such a light wind as Wind Factor 1. The American commander thought that he might be able to make it around faster, without losing much ground, by wearing. The Phoebe had suffered delay in getting her head around in the previous 12:50 tack. Hopefully Essex could finally gain the wind advantage. The American commander was wrong. Phoebe again tacked at 2:26 and this time came smartly around despite the light wind condition. Essex actually lost ground by her wearing maneuver. The two ships again crossed paths at 2:50, the heavy carronades of Essex inflicting more hits upon the hull of Phoebe. The accumulated punishment of Phoebe's hull finally showed fruit in a reduction of firepower in the British ship. Phoebe's high fire inflicted damage upon both the sails and the lower mizzen mast of the American ship, but Essex still retained her superiority in speed.

In a sudden flash of Yankee ingenuity, the American commander now decided upon a different maneuver to bring his British opponent to close action. Instead of the previous series of long opposing tacks and occasional broadsides in passing, Essex tacked immediately (2:53) in the wake of the passing Phoebe and came upon a WNW course parallel to the British ship and very slightly to leeward. With her advantage in speed, Essex would ultimately overtake her British opponent and be able to fight within carronade range. If Phoebe attempted to tack away in reply, her stern would be exposed to raking fire for several minutes; if she wore around, she would surrender the wind advantage to Essex. This constituted an act of blinding tactical brilliance on the part of the humble American commander. In the event, the British commander chose to run for it. Phoebe had gained some distance in the time it took Essex to complete her tack and a lengthy stern chase ensued. At 4:20, the wind shifted from NW to NNE, finally giving Essex the wind advantage, and at 5:40 shifted again from NNE to ENE. Essex gained yard by excruciating yard upon her quarry. After a three hour stern chase, the port quarter of Phoebe came finally within carronade range at 5:50, whereupon a spirited twenty minute exchange of fire ensued between the port after gun battery of Phoebe and the forward starboard gun battery of Essex. It is sad to say that the Essex gunners fired poorly and inflicted only negligible damage upon their target. The same cannot be said for the gunners of Phoebe. Perhaps inspired by their desperate circumstances, they succeeded in throwing some seriously hot gunnery dice and inflicted enough damage upon the sails and rigging of Essex to reduce her to a slight inferiority in speed. Phoebe was too injured in her hull to stay and continue the fight, but she was now creeping away, yard by yard, from her American pursuer. The American commander was far more than a little annoyed at this development, as he watched apparent victory slip from his outstretched grasp. At 6:13, in a desperate maneuver, he turned his ship to the NW and brought his fresh port battery to rake the exposed stern of the fleeing Phoebe. The British commander erred by not turning away to protect his stern and Phoebe consequently endured a thunderous raking broadside which shattered her hull, but ironically failed to slow the British ship. The American commander had made a terrible mistake by failing to direct his broadside aloft at Phoebe's sails. It now being just after sunset, it was agreed that a visibility test was in order. The dice were thrown and, lo and behold, fortune again favored the British as visibility maliciously fell to less than one sea mile (2000 yards). A quick check of the repair rules showed that Phoebe would be long gone in the gathering murk before Essex could sufficiently repair her damages aloft and resume pursuit. Phoebe disappeared into the overcast with about 35 percent crew casualties, her gun power down by two thirds, her rigging and sails about 30 percent damaged, with her jib boom shot away and all her lower masts slightly injured. Essex had suffered less than 10 percent casualties among her crew and guns, but her 40 percent loss in rigging and sails, with her mizzen topmast and lower mizzenmast both shot half through, denied her the fruits of a hard fight. The American commander could claim only a minor victory, for no British ship had been lost. He nevertheless took comfort in the fact that John Bull had fled before the guns of a stout American ship. The British commander, for his part, duly informed the Admiralty that his American quarry, so superior to Phoebe in sailing qualities and armament, had reneged upon an honorable promise to fight to the finish and disappeared in the gathering murk of the Pacific night after a hard fought battle - and so was it written into British naval history.

This Age of Sail scenario was recently played by two old wargaming tars, Byron Angel and Phil Jarvio, on a Wednesday night in October, 1998. Byron played the American commander, while Phil portrayed the British commander. The game was played with 1:2000 scale Valiant ship models in true time/distance scale upon a six foot by eight foot table. Occasional re-positioning of the ships was required to keep play on the tabletop. The rules in use were Byron's Age of Sail rule set (working title: "Man of War"), which he started in 1984 and has proudly maintained under play test and refinement mode for the past fifteen years.

This Age of Sail scenario was recently played by two old wargaming tars, Byron Angel and Phil Jarvio, on a Wednesday night in October, 1998. Byron played the American commander, while Phil portrayed the British commander. The game was played with 1:2000 scale Valiant ship models in true time/distance scale upon a six foot by eight foot table. Occasional re-positioning of the ships was required to keep play on the tabletop. The rules in use were Byron's Age of Sail rule set (working title: "Man of War"), which he started in 1984 and has proudly maintained under play test and refinement mode for the past fifteen years.

Ship Name Tons L Guns Carr Speed Crew

Morale USS ESSEX 800 1 8 13 Veteran High

HMS PHOEBE 900 3 3 12 Veteran High

HMS CHERUB 500 - 4 13 Trained High

Map

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #76

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com