In the breach, VLB failed. Apparently, in the absence of George Jeffrey himself to explain the rules, the mechanics were too unfamiliar, the rulebook too vague. Even when George put on a VLB game, not everyone was satisfied. One of my friends played in his game and reported to me, "you know, he's just making this up as he goes!" Indeed, because VLB opens a game to many more of the encounters and events that actually characterizes combat, I believe it is impossible to write a rulebook that comprehensively codifies how to adjudicate everything. Thus, when playing my own version of VLB today, we still occasionally have "to make something up." But perhaps this is not as bad as it sounds. VLB provides an objective framework, time, to apply to novel situations. When an unforseen event occurs, I find that most of my friends and I can jointly agree how to make a ruling. This approach is not for everyone.

Halfway through one VLB game, a good friend said, "I hate this VLB ##*f! Caveats aside, the following battle report illustrates why a VLB game can be so much fun. I will not describe my tactical rules since I have written about them in these pages before and your preferred rule set can probably be modified to accommodate the VLB approach. In the unlikely event that readers clamor for tactical rule details, perhaps our editor will notify me and I'll write more. But in what follows, the rules specific to VLB will be emphasized. It is a Napoleonic game, but the VLB concept applies to any period except, perhaps, the modem era.

However, because of Napoleon's superior strategy, the French outnumber Blucher's allied army. Blucher commands 45,000 infantry, 8,000 cavalry, and 80 guns. Opposing him are 58,000 French infantry 14,000 cavalry, and 150 guns. If, by day's end Napoleon retains a toehold in Dulchy le Chateau or possesses both the Roman and the Soissons roads, the French win. February fog in the Marne Vallev lifts at 8 A.M. Darkness, and game's end, will occur sometime between 5:30 and 7 P.M.

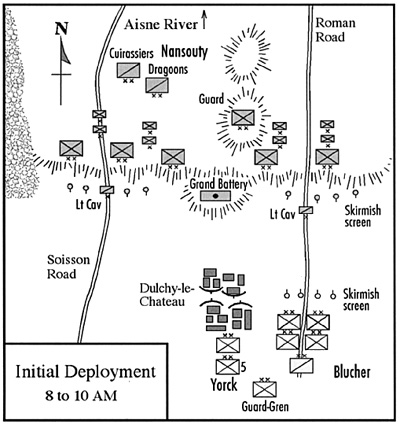

By rule, the French must position their light cavalry astride the two roads. The French players evenly distribute their forces in conventional manner across the entire front. Skirmishers make up the front rank, infantry deployed in line with artillery in the intervals form the second rank, while infantry in column serve in the third rank as a counterattack force. Most of the French cavalry and the Imperial Guard provide a powerful reserve. A grand battery on the heights behind Dulchy le Chateau supports the defenders in the village. Because he did not arrive until dark, Blucher did not have a 6hance to reconnoiter before drawing up his plans. In the absence of scouting intelligence, he decides to refuse his left and hurl four of his seven infantry divisions, all his cavalry, and 60 guns up the Roman Road on his right. He details two divisions and two batteries to capture Dulchy le Chateau and keeps the Prussian Guard and Grenadiers in reserve.

Only deployed forces (forces that have deployed from march column into combat formation) can make an approach march. Before beginning an approach march, units must be within 1,000 meters of the target and must be aligned so that they face their target. During the approach march, they cannot deviate by more than 10 degrees from a direct march toward the target. Infantry in column and cavalry require 15 minutes to complete the approach march, regardless of distance but not to exceed 1,000 meters. Infantry in line requires 30 minutes. The initial Prussian attack east of Dulchy le Chateau illustrates what this means in practice. The four attacking divisions composed two corps. Corps deployment lasted from 8 A.M. to 10 A.M. at which time Blucher announced he was making an approach march. He advances with two divisions abreast, each division in column of brigades with the brigades deployed in battalion columns. Thus the approach march consumes 15 minutes. During this time the rival skirmish lines engage. Skirmishers fire once and then retire behind the formed troops to which they are attached. The Prussian skirmish screen (fusiliers, schutzen, and volunteer jagers ) gain partial skirmish superiority over the French voltigeurs (Recall in 1813-1814 Prussian tactical doctrine put more men in a skirmish role than did the French). The Prussian skirmishers begin to deliver an unsettling fire on the French front line. Meanwhile, the French divisional artillery fires ball at the Prussian infantry columns. Once the rival skirmishers clear the front the French guns switch to canister. At this point, before the infantry engage, both sides assess morale. One of the main attractions to VLB games is that instead of focusing on a series of individual events, you consider what has happened over a period of time. In this case, the Prussians have suffered some disorganization from artillery fire while making their approach march and significant losses from the canister fire. Now they see an imposing enemy line of muskets. These effects are aggregated and applied to the morale check. In the Prussian front ranks, the landwehr and some of the reserve infantry balk (fail morale). However, the veteran line and some of the reserve infantry press forward. The defenders are all enthusiastic conscripts, the famous Marie Louises. While some are shaken by the combination of the Prussian's effective skirmish fire and the imposing sight of the Prussian columns, the majority stand firm. The fact that Blucher is in a hurry and has dispensed with any preparatory bombardment helps. During the ensuing close combat, the French repulse the first Prussian assault. By rule, all combat takes 15 minutes.

Two playing aids greatly help maintain order in the VLB game. First, I have a hand-made clock that I manually advance to indicate current battlefield time. Second, I have a set of gaming counters (old Avalon Hill counters flipped over) marked with time labels in 15 minute intervals. We place these unobtrusive markers by the units to indicate the earliest that the units are available for further movement. To make the VLB system faithfully reproduce realistic battlefield constraints, it is important to follow the historic chain of command. In the pages of "Empire, Eagles, and Lions," Jean Lochet and comrades have written extensively and usefully about this topic. As they and others suggest, there are many ways to approach command and control. Here is my approach: All subordinate, non-playing corps and divisional commanders are given a value called an initiative rating. This rating is a reflection of their own capacity and the ability of their staffs. The player tests on behalf of these subordinate whenever they receive new orders. Meeting the point or rolling under it allows the player to move the appropriate units immediately. Failure requires a second roll using a D6: 1,2 = 45 minute delay; 3-4 = 30 minute delay; 5,6 = 15 minute delay. Orders come from a player, move by courier, and take 15 minutes at each command level. For example, a player acting as army commander writes an order (15 minutes), the courier moves up to 70 inches, (15 minutes), and the message is filtered down through the command chain with each step (corps/div/bde/reg) requiring 15 minutes each. In addition the corps and divisional commanders will have to make an initiative roll to forward the order in a timely manner. Active players do not have an initiative rating but they still must observe the time delays associated with the transmission of orders through the chain of command. Charismatic leaders -- my list includes Napoleon, Blucher, Ney among others - can ride to a unit and personally give orders. This can shorten the amount of time required to get a unit moving, but don't over do this or you will return to the overly precise command and control that characterizes most games.

Returning to our game, Blucher anticipated that his initial assault was unlikely to succeed against his more numerous foe who manned a fine defensive position. That is why he massed his forces to achieve local, numerical superiority. As soon as his first wave was repulsed, the second wave advanced. This was by pre-arrangement in that the initial Prussian orders specified that all four right wing divisions were to attack and the initial deployment dictated how many brigades would advance m each wave. The only unknown was when the second Prussian assault would go in. Blucher hoped it would occur hard on the heels of the first attack, but the exact timing was out of his hands. This is another realistic advantage of the VLB system. To advance, the second wave had to wend its way through the debris of the shattered first wave. As those readers who have played my "Generalship" rules know, here I employ a table called "the passage of the lines" (the last table I will refer to in this article, I promise!) The roll is adversely modified by critical threats (situations that endanger morale), rough terrain, and when passing through routed/retreated/shaken forces. Columns are handier than lines and so the roll is enhanced if the unit is in column. Failure to pass the lines causes the unit to halt/shaken for 30 minutes.

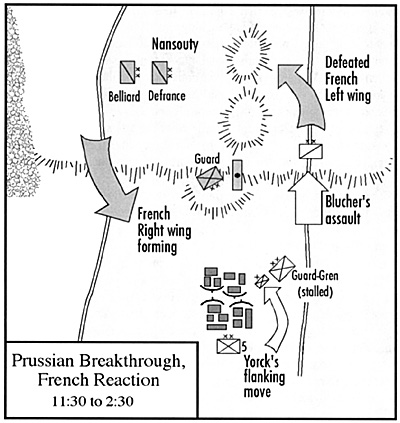

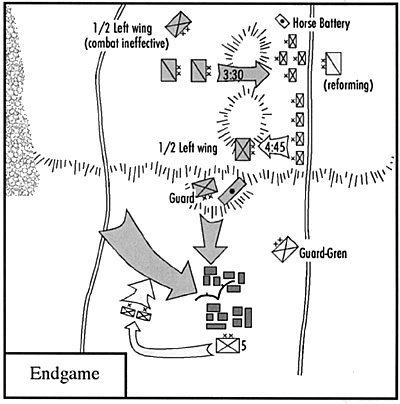

This counterattack restores the ridge top position but the Prussian attack in depth allows Blucher to throw fresh against tired troops. Finally, at 11:45 the Prussians gain a clean breakthrough. All of this came about as a consequence of the rival players' initial orders and deployment. Neither team did anything to interrupt the course of fate. Indeed, unless someone had immediately divined their opponent's plan and except for committing reserves - and both sides were experienced enough to know that it was unwise to throw in the reserves so early in the battle -- there was not much either team could do. The VLB system had allowed the players to sit back and watch events unfold. How different arc most games where the rivals try to manipulate play to gain an advantage. Once Napoleon appreciated that the weight of the Prussian attack was directed against his left, he sent orders to his un-engaged wing to wheel to the east, advance, and drive all before it. Ever the master artillerist, Napoleon rode to the grand battery and repositioned it so it could deliver effective enfilade fire against the Prussian attacking wing. Simultaneously, Blucher's subordinate, General Yorck (me!), led his command against the French-controlled half of Dulchy le Chateau. Recall that the Prussians cannot win unless they capture the village. Yorck's problems are the intrinsic defensive advantages of a village built largely out of stone and the lack of Prussian deployment space. To Blucher's despair, Yorck's assaults go in piecemeal and fail to gain control of the entire village. Worse, when Yorck tries to work around the village's eastern side, his troops interfere with the movement of the Prussian reserves. Unbeknownst to Yorck, Blucher had ordered his elite units to assault the flank of the grand battery. When Blucher issued this order, there was a clear path to the target. By the time the reserve division actually moved, my units blocked them. An amusing series of messages passed between Blucher and Yorck, some of them "crossing" one another, which only led to more confusion. A costly traffic jam that lasted until close to 2 P.M. ensued. During this time the Prussian right wing swept forward along the Roman Road. As is so often the case with a linear defense, once the crust is burst, the attacker has a great opportunity to exploit success. Reacting to this threat, Napoleon ordered a powerful French cavalry counterattack into the flank of the Prussian assault wing. That's what happened, here's how the VLB system controlled it. The Prussian ridge top victory occurred at 11:45. Blucher ordered his cavalry through the breach, but this move required a passage of the lines and a 30 minute delay ensued. By 12:45 the Prussian cavalry controlled the Roman Road but required new orders to turn west to face the French reserves. The time consumed in writing and transmitting orders and re-deploying the corps meant that the Prussian cavalry was not in battle formation facing east until 3:30. Meanwhile, at noon Napoleon shifted the Guard to support the grand battery. When he saw the Prussian cavalry trying to work through the hole in his line, he sent orders to his cavalry to seal the breach. As is often the case in VLB games, a race ensued to see who would get in the first blow. But neither Napoleon nor Blucher could do anything to hasten the movements of the rival cavalries! Each of the following operations took 15 minutes: Napoleon's order; courier move; Nansouty (cavalry corps commander) reads the order and passes initiative so there is no delay; Defrance (dragoon division) and Belliard (cuirassier division) read orders and pass initiative. So, between 1 and 3 P.M Nansouty's Corps redeploys. By 3:15 it is within striking distance of the Prussian cavalry and announces an approach march. By the narrowest the Prussians are ready. However, the Peninsular veterans from Spain, who compose Defrance's dragoon division, defeat the Prussian cavalry whose ranks include a large contingent of unreliable landwehr and freikorps troopers. The battle for control of the Roman Road hinges on the ability of a handful of Prussian infantry units, the Elbe landwehr and Hellwig's Streifkorps supported by an active horse artillery battery, to form square and hold. When they succeed, half of the Prussian victory terms are in hand. Victory depends on who controls Dulchy le Chateau. It did not take a genius to anticipate that at some point the un-engaged French wing would move toward the sound of the guns. It also seemed likely that the French would send the majority of this force to succor the defenders of the village. As Yorck, my problem was that in the absence of the Prussian reserve division. which lay pinned by the fire of the French grand battery, one-half the French army outnumbered my two-sevenths of the Prussian army. Having already committed one division in a heretofore futile assault on the village, I had only one division, the 5th Division, left. It was already in march column, which facilitated rapid maneuver. The French, on the other hand had to form march column before beginning their advance. If the French player maneuvered as I expected, it would be something like two and one half hours before his fresh troops arrived outside of the village. Then they would have to deploy into battle formation. So, the French would experience a window of vulnerability lasting at least an hour. I wrote an order sending the 5th Division to a position west of Dulchy le Chateau where it was to deploy facing south-west and attack what I hoped would be the flank of the French while they were deploying to attack the village. In the event, the 5th Division's attack triumphed famously. The French could simply not react in time. Much like the British attack at Salamanca in 1812, the Prussians took unit after unit in flank before the French could turn to face the threat. All of this was well and good, but it would not have mattered had not the Prussians enjoyed great, good luck in Dulchy le Chateau itself.

Before noon Yorck had been able to clear the southwestern quadrant of the village, albeit at the expense of blocking the Prussian reserves. An advance against the village's northwestern quadrant had to brave fire from the French guns on the heights behind Dulchy le Chateau and this proved impossible. Finally, around 4:45, the Prussian assault wing recovered from the onslaught of the French cavalry and attacked the heights. They managed to distract the French grand battery and permit Yorck to attack the remaining French-held houses from two directions. With a cheer, my Prussians swept through the rubble and captured Dulchy le Chateau. But Yorck's joy was short-lived. Napoleon had stationed his Guard in close support. The Prussian success triggered a timely counterattack by the 3rd Grenadiers. At bayonet point the Dutch guardsmen drove my fusiliers from their dearly purchased objective.

In real time, the battle lasted close to four and one-half hours. For me, this is a longer than usual game. However, it featured an unusual number of figures (something on the order of 2,500, 25mm figures) and involved two players who, although experienced Napoleonic gamers, had never played a VLB game. To my immense relief everyone enjoyed the game. Pairing the VLB rookies on the same side but in command of the bigger French force in a strong position proved a good technique for handicapping the game so that both sides felt they had good chances to win. All players agreed that the game's most notable characteristic was the realistic manner in which they had to make decisions and then watch, at times with dread, as their orders were executed and time marched inexorably on.

Several years ago George Jeffrey introduced a wargaming concept for Napoleonic miniatures that he called the Variable Length Bound (VLB) (see the Courier, Vol. III No. 3 - 6 and Vol. IV, No. 1). Instead of movement defined by a specified number of inches per turn, VLB proposed that movement be defined by how far a unit could march in a specified amount of time. There were no turns, per se, but rather a sequential series of bounds. A bound's endpoint was combat. A bound might represent 15 minutes or, during a period of extensive maneuver, it might last an hour or more. VLB was an elegant concept that gave promise of an entirely different wargame with a realistic flow. Among its early partisans was our distinguished editor who wrote that VLB would revolutionize wargaming.

Several years ago George Jeffrey introduced a wargaming concept for Napoleonic miniatures that he called the Variable Length Bound (VLB) (see the Courier, Vol. III No. 3 - 6 and Vol. IV, No. 1). Instead of movement defined by a specified number of inches per turn, VLB proposed that movement be defined by how far a unit could march in a specified amount of time. There were no turns, per se, but rather a sequential series of bounds. A bound's endpoint was combat. A bound might represent 15 minutes or, during a period of extensive maneuver, it might last an hour or more. VLB was an elegant concept that gave promise of an entirely different wargame with a realistic flow. Among its early partisans was our distinguished editor who wrote that VLB would revolutionize wargaming.

THE SITUATION

It is the winter of 1814 in France. In a dazzling strategic display, Napoleon has isolated Blucher's Prussian/Russian army and occupied their principal line of communication. To break free, Blucher must attack the French who occupy a ridge top position blocking Blucher's escape route over the Aisne River. To accomplish his objective, Blucher must open one of the two north-south roads and capture the village of Dulchy le Chateau (See map. The previous evening, an inspired assault by Blucher's advance guard carried half the village. Because his army is low on supplies, today he must break free or perish.

It is the winter of 1814 in France. In a dazzling strategic display, Napoleon has isolated Blucher's Prussian/Russian army and occupied their principal line of communication. To break free, Blucher must attack the French who occupy a ridge top position blocking Blucher's escape route over the Aisne River. To accomplish his objective, Blucher must open one of the two north-south roads and capture the village of Dulchy le Chateau (See map. The previous evening, an inspired assault by Blucher's advance guard carried half the village. Because his army is low on supplies, today he must break free or perish. PLANS AND DISPOSITIONS

THE MATTER OF TIME

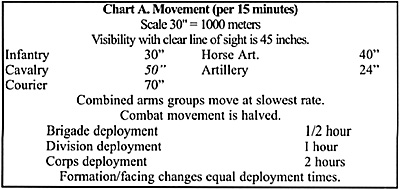

Movements are coordinated using the accompanying table showing time and movement. It is derived from my own research, information published in George Jeffrey's Tactics and Grand Tactics of the Napoleonic Wars, and various articles written by the prolific George Nafziger. A 15 minute increment is the smallest, discrete measure of time I use. A glance at Chart A, where march movement indicates all movement behind friendly lines and combat movement applies to units in the front line, will make it clear that even on my 14' x 6' table, units will quickly be in contact. VLB, coupled with the long movement distances, requires a rules convention that I call the "approach march". Before combat, an attacking force must inform the defender which forces are making an approach march.

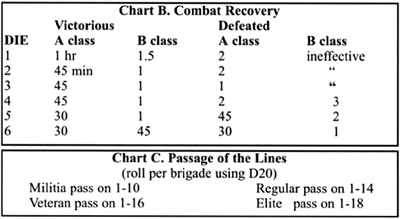

Movements are coordinated using the accompanying table showing time and movement. It is derived from my own research, information published in George Jeffrey's Tactics and Grand Tactics of the Napoleonic Wars, and various articles written by the prolific George Nafziger. A 15 minute increment is the smallest, discrete measure of time I use. A glance at Chart A, where march movement indicates all movement behind friendly lines and combat movement applies to units in the front line, will make it clear that even on my 14' x 6' table, units will quickly be in contact. VLB, coupled with the long movement distances, requires a rules convention that I call the "approach march". Before combat, an attacking force must inform the defender which forces are making an approach march.  Both sides now consult the recovery table (Chart B). "A Class" troops refers to line and better. "B Class" are conscripts, freicorps, landwehr and their ilk. The die roll specifies how much time elapses before the combat-tired units can return to the fray. Note that poorer quality troops may not return at all if they roll "combat ineffective." Once the appropriate amount of time has passed, the recovered units are considered to be in march column, and thus must take time to deploy before re-entering combat. They also require new orders.

Both sides now consult the recovery table (Chart B). "A Class" troops refers to line and better. "B Class" are conscripts, freicorps, landwehr and their ilk. The die roll specifies how much time elapses before the combat-tired units can return to the fray. Note that poorer quality troops may not return at all if they roll "combat ineffective." Once the appropriate amount of time has passed, the recovered units are considered to be in march column, and thus must take time to deploy before re-entering combat. They also require new orders.  At the Battle of Dulchy le Chateau, the Prussian second wave attacks in a timely manner with a new 15 minutes approach march and overcomes the combat weakened defenders (another 15 minute fight). The defeat of the French front line triggers a counterattack by the local French reserves (15 minute approach march).

At the Battle of Dulchy le Chateau, the Prussian second wave attacks in a timely manner with a new 15 minutes approach march and overcomes the combat weakened defenders (another 15 minute fight). The defeat of the French front line triggers a counterattack by the local French reserves (15 minute approach march). Yorck: "Can you support me with the reserves?"

Blucher: "Can you get out of my way?"

Yorck: "I see your reserves standing idle. Cannot they do something?'

Blucher: "I'm trying to attack the grand battery. Get out of my way!"

Yorck: "If the reserves would clear my front I could more effectively attack the village." Scrapping together all recovered Prussian units, Yorck launched one last effort. The odds of success were something on the order of one in four. But, as you know, the victors write the history and so indeed this last, desperate Prussian assault managed to evict the Dutch from the village. Mercifully, this occurred just before the onset of darkness (determined by a die roll) and so the Battle of Dulchy le Chateau ended in Prussian victory.

Scrapping together all recovered Prussian units, Yorck launched one last effort. The odds of success were something on the order of one in four. But, as you know, the victors write the history and so indeed this last, desperate Prussian assault managed to evict the Dutch from the village. Mercifully, this occurred just before the onset of darkness (determined by a die roll) and so the Battle of Dulchy le Chateau ended in Prussian victory.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #75

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com